Chapter 19 the GROUP VIB(16) ELEMENTS: SULFUR, SELENIUM, TELLURIUM, and POLONIUM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Preparation of Telluric Acid from Tellurium Dioxide by Oxidation with Potassium Permanganate Frank C. Mathers, Charles M. Rice, Howard Broderick, and Robert Forney, Indiana University General Statement Tellurium dioxide, Te0 2 , although periodically similar to sulfur dioxide, cannot be oxidized by nitric acid to the valence of six, i.e., to telluric acid, H 2 Te04.2H 2 0. Among the many stronger oxidizing agents that will produce this oxidation, potassium permanganate in a nitric acid solution is quite satisfactory. This paper gives directions and data for the preparation of telluric acid by this reaction. The making of telluric acid is a desirable laboratory experiment because (1) tellurim dioxide is available in large quantities and is easily obtained, (2) the telluric acid is a stable compound, easily purified, easily crystallized, and non-corrosive, and (3) students are interested in experimenting with the rarer elements. The small soluibility of telluric acid and the high solubility of both manganese and potassium nitrates in nitric acidi gives a sufficient differ- ence in properties for successful purification by crystallization of the telluric acid. Methods of Analyses Tellurium dioxide can be volumetrically 2 titrated in a sulfuric acid solution by an excess of standard potassium permanganate, followed by enough standard oxalic acid to decolorize the excess of permanganate. The excess of oxalic acid must then be titrated by more of the perman- ganate. The telluric acid can be titrated, like any ordinary monobasic acid, 3 (1911). with standard sodium hydroxide using phenolphthalein as an indicator, if an equal volume of glycerine is added. If any nitric acid is present, it must be neutralized first with sodium hydroxide, using methyl orange as indicator. -

540.14Pri.Pdf

Index Element names, parent hydride names and systematic names derived using any of the nomenclature systems described in this book are, with very few exceptions, not included explicitly in this index. If a name or term is referred to in several places in the book, the most informative references appear in bold type, and some of the less informative places are not cited in the index. Endings and suffixes are represented using a hyphen in the usual fashion, e.g. -01, and are indexed at the place where they would appear ignoring the hyphen. Names of compounds or groups not included in the index may be found in Tables P7 (p. 205), P9 (p. 232) and PIO (p. 234). ~, 3,87 acac, 93 *, 95 -acene, 66 \ +, 7,106 acetals, 160-161 - (minus), 7, 106 acetate, 45 - (en dash), 124-126 acetic acid, 45, 78 - (em dash), 41, 91, 107, 115-116, 188 acetic anhydride, 83 --+, 161,169-170 acetoacetic acid, 73 ct, 139, 159, 162, 164, 167-168 acetone, 78 ~, 159, 164, 167-168 acetonitrile, 79 y, 164 acetyl, III, 160, 163 11, 105, 110, 114-115, 117, 119-128, 185 acetyl chloride, 83, 183 K, 98,104-106,117,120,124-125, 185 acetylene, 78 A, 59, 130 acetylide, 41 11, 89-90,98, 104, 107, 113-116, 125-126, 146-147, acid anhydrides, see anhydrides 154, 185 acid halides, 75,83, 182-183 TC, 119 acid hydrogen, 16 cr, 119 acids ~, 167 amino acids, 25, 162-163 00, 139 carboxylic acids, 19,72-73,75--80, 165 fatty acids, 165 A sulfonic acids, 75 ct, 139,159,162,164,167-168 see also at single compounds A, 33-34 acrylic acid, 73, 78 A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic actinide, 231 Compounds, 4, 36, 195 actinoids (vs. -

Kinetics and Mechanism of Polythionate Oxidation to Sulfate at Low Ph by O2 and Fe3+

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 67, No. 23, pp. 4457–4469, 2003 Copyright © 2003 Elsevier Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0016-7037/03 $30.00 ϩ .00 doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00388-0 3؉ Kinetics and mechanism of polythionate oxidation to sulfate at low pH by O2 and Fe 1, 2 1,2 GREGORY K. DRUSCHEL, *ROBERT J. HAMERS, and JILLIAN F. BANFIELD † 1Departments of Geology and Geophysics and 2Chemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706 USA (Received October 16, 2002; accepted in revised form May 30, 2003) 2Ϫ Abstract—Polythionates (SxO6 ) are important in redox transformations involving many sulfur compounds. Here we investigate the oxidation kinetics and mechanisms of trithionate and tetrathionate oxidation between pH 0.4 and pH 2 in the presence of Fe3ϩ and/or oxygen. In these solutions, Fe3ϩ plus oxygen oxidizes tetrathionate and trithionate at least an order of magnitude faster than oxygen alone. Kinetic measurements, coupled with density functional calculations, suggest that the rate-limiting step for tetrathionate oxidation involves Fe3ϩ attachment, followed by electron density shifts that result in formation of a sulfite radical and 0 S3O3 derivatives. The overall reaction orders for trithionate and tetrathionate are fractional due to rearrange- ment reactions and side reactions between reactants and intermediate products. The pseudo-first order rate coefficients for tetrathionate range from 10Ϫ11 sϪ1 at 25°C to 10Ϫ8 sϪ1 at 70°C, compared to 2 ϫ 10Ϫ7 sϪ1 Ϯ at 35 °C for trithionate. The apparent activation energy (EA) for tetrathionate oxidation at pH 1.5 is 104.5 4.13 kJ/mol. -

Substitution and Redox Chemistry of Ruthenium Complexes

iJ il r¿ SUBSTITUTION AND REDOX CHEMISTRY OF RUTHENIUM COMPLEXES by Paul Stuaft Moritz, B. Sc. (Hons) * A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The Department of Physical and lnorganic Chemistry, The University of Adelaide. JUNE 1987 lìr.+:-c{,¡l I /tz lZ]' STATEMENT. This Thesis conta¡ns no materialwhich has been accepted for the award of any other Degree or Diploma in any University and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. I give consent that, if this Thesis is accepted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, it may be made available for photocopying and, if applicable, loan. Moritz. SUMMARY The coordination chemislry of ruthenium is domínated by the oxidation states, +2 and +3. Within these oxidation states, the ammine complexes form a large and welt- characterized group. This thesis reports on the chemistry of lhe hitherto neglected triammine complexes, with particular reference to their redox chemistry, and the possible formation of Ru(lV) triammine complexes with terminal oxo ligands. The chemistry of the +4 oxidation state is further explored through the formation of stable chelate complexes. The salt, [Ru(NH3)3(OH2)31(CFgSO3)3, was prepared by hydrotysis of Ru(NHs)sCts in triflic acid solution. lts spectra, electrochemistry and substitution reactions are similar to those of the well-known hexa-, penta-, and tetraammine complexes. At freshly polished platinum and glassy carbon electrodes, a quasi reversible redox wave was detected, corresponding to a proton-coupled reduction involving the pu3+7pu2+ couple. -

Deracemization of Sodium Chlorate with Or Without the Influence of Sodium Dithionate Manon Schindler

Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate Manon Schindler To cite this version: Manon Schindler. Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate. Cristallography. Normandie Université, 2020. English. NNT : 2020NORMR004. tel- 02521046v2 HAL Id: tel-02521046 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02521046v2 Submitted on 15 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE Pour obtenir le diplôme de doctorat Spécialité Physique Préparée au sein de l’Université de Rouen Normandie Deracémisation du chlorate de sodium avec et sans l’influence du dithionate de sodium Présentée et soutenue par Manon SCHINDLER Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 mars 2020 devant le jury composé de Mme. Elizabeth HILLARD Dr. Hab. Université de Bordeaux Rapporteur M. Elias VLIEG Pr. Université Radboud de Nimègue Rapporteur Mme. Sylvie MALO Pr. Université de Caen Normandie Présidente M. Woo Sik KIM Pr. Université Kyung Hee de Séoul Examinateur M. Gérard COQUEREL Pr. Université de Rouen Normandie Directeur de thèse Thèse dirigée par Gérard COQUEREL, professeur des universités au laboratoire Sciences et Méthodes Séparatives (EA3233 SMS) THÈSE Pour obtenir le diplôme de doctorat Spécialité Physique Préparée au sein de l’Université de Rouen Normandie Deracemization of sodium chlorate with or without the influence of sodium dithionate Présentée et soutenue par Manon SCHINDLER Thèse soutenue publiquement le 13 mars 2020 devant le jury composé de Mme. -

WO 2012/024294 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date Λ 23 February 2012 (23.02.2012) WO 2012/024294 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C22B 47/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (21) International Application Number: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, PCT/US201 1/047916 DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, 16 August 201 1 (16.08.201 1) KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (25) Filing Language: English NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 61/374,691 18 August 2010 (18.08.2010) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AMER¬ kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, ICAN MANGANESE INC. [CA/US]; 2533 North Car GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, son Street, Suite 3913, Carson City, NV 89706 (US). -

Cryptic Role of Tetrathionate in the Sulfur Cycle: a Study from Arabian Sea Oxygen Minimum Zone Sediments

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/686469; this version posted July 2, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Cryptic role of tetrathionate in the sulfur cycle: A study from Arabian Sea oxygen minimum zone sediments Subhrangshu Mandal1, Sabyasachi Bhattacharya1, Chayan Roy1, Moidu Jameela Rameez1, 5 Jagannath Sarkar1, Svetlana Fernandes2, Tarunendu Mapder3, Aditya Peketi2, Aninda Mazumdar2,* and Wriddhiman Ghosh1,* 1 Department of Microbiology, Bose Institute, P-1/12 CIT Scheme VIIM, Kolkata 700054, India. 2 CSIR-National Institute of Oceanography, Dona Paula, Goa 403004, India. 10 3 ARC CoE for Mathematical and Statistical Frontiers, School of Mathematical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australia. * Correspondence emails: [email protected] / [email protected] 15 Running Title: Tetrathionate metabolism in marine sediments KEYWORDS: sulfur cycle, tetrathionate, marine oxygen minimum zone, sediment biogeochemistry 20 ABSTRACT To explore the potential role of tetrathionate in the sulfur cycle of marine sediments, the population ecology of tetrathionate-forming, oxidizing, and respiring microorganisms was revealed at 15- 30 cm resolution along two, ~3-m-long, cores collected from 530- and 580-mbsl water-depths of Arabian 25 Sea, off India’s west coast, within the oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). Metagenome analysis along the two sediment-cores revealed widespread occurrence of the structural genes that govern these metabolisms; high diversity and relative-abundance was also detected for the bacteria known to render these processes. Slurry-incubation of the sediment-samples, pure-culture isolation, and metatranscriptome analysis, corroborated the in situ functionality of all the three metabolic-types. -

Stable Allotropes of Oxygen Are O2(G) and O3(G)

Group 16 Elements - Oxygen ! Stable allotropes of oxygen are O 2(g) and O 3(g). ! Standard laboratory preparations for O 2(g) include the following: MnO 2 2KClO 3 ∆ 2KCl + 3O 2 2HgO ∆ 2Hg + O 2 electrolysis 2H 2O 2H 2 + O 2 ! O2(g) is paramagnetic due to two unpaired electrons in π σ 2 σ 2 σ 2 π 4 π 2 separate * MOs: ( 2s) ( *2s) ( 2p) ( 2p) ( *2p) • Bond order is 2, and the bond length is 120.75 pm. ! Ozone is produced by passing an electric discharge through O2(g). • It is produced naturally by u.v. (240-300 nm). hν O2 2O O + O 2 ÷ O 3 ! Ozone is a bent molecule ( pO–O–O = 116.8 o). • Bond order is 1½ for each O–O bond, and the bond length is 127.8 pm. ! Both O 2 and O 3 are powerful oxidizing agents. + – o O2 + 4H + 4 e ÷ 2H 2O E = +1.23 V + – o O3 + 2H + 2 e ÷ O 2 + H 2O E = +2.07 V Group 16 Elements - Sulfur ! Sulfur is found free in nature in vast underground deposits. • It is recovered by the Frasch process, which uses superheated steam to melt and expel the fluid. Sulfur Allotropes ! Three principal allotropes: o o rhombic, S 8 (<96 C, mp = 112.8 C) o o monoclinic, S 8 (>96 C, mp = 119. C) amorphous, S n (metastable "plastic" sulfur) • Rhombic and monoclinic forms contain crown-shaped S 8 rings ( D4d). • Amorphous sulfur, containing long S n chains, is formed when molten sulfur is rapidly quenched; conversion to rhombic S 8 can take years. -

A Novel Bacterial Thiosulfate Oxidation Pathway Provides a New Clue About the Formation of Zero-Valent Sulfur in Deep Sea

The ISME Journal (2020) 14:2261–2274 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0684-5 ARTICLE A novel bacterial thiosulfate oxidation pathway provides a new clue about the formation of zero-valent sulfur in deep sea 1,2,3,4 1,2,4 3,4,5 1,2,3,4 4,5 1,2,4 Jing Zhang ● Rui Liu ● Shichuan Xi ● Ruining Cai ● Xin Zhang ● Chaomin Sun Received: 18 December 2019 / Revised: 6 May 2020 / Accepted: 12 May 2020 / Published online: 26 May 2020 © The Author(s) 2020. This article is published with open access Abstract Zero-valent sulfur (ZVS) has been shown to be a major sulfur intermediate in the deep-sea cold seep of the South China Sea based on our previous work, however, the microbial contribution to the formation of ZVS in cold seep has remained unclear. Here, we describe a novel thiosulfate oxidation pathway discovered in the deep-sea cold seep bacterium Erythrobacter flavus 21–3, which provides a new clue about the formation of ZVS. Electronic microscopy, energy-dispersive, and Raman spectra were used to confirm that E. flavus 21–3 effectively converts thiosulfate to ZVS. We next used a combined proteomic and genetic method to identify thiosulfate dehydrogenase (TsdA) and thiosulfohydrolase (SoxB) playing key roles in the conversion of thiosulfate to ZVS. Stoichiometric results of different sulfur intermediates further clarify the function of TsdA − – – – − 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: in converting thiosulfate to tetrathionate ( O3S S S SO3 ), SoxB in liberating sulfone from tetrathionate to form ZVS and sulfur dioxygenases (SdoA/SdoB) in oxidizing ZVS to sulfite under some conditions. -

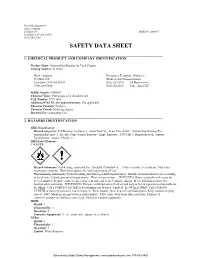

Safety Data Sheet

World Headquarters Hach Company P.O.Box 389 MSDS No: M00107 Loveland, CO USA 80539 (970) 669-3050 SAFETY DATA SHEET _____________________________________________________________________________ 1. CHEMICAL PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Hydrosulfite Reagent for Total Copper Catalog Number: 2118869 Hach Company Emergency Telephone Numbers: P.O.Box 389 (Medical and Transportation) Loveland, CO USA 80539 (303) 623-5716 24 Hour Service (970) 669-3050 (515)232-2533 8am - 4pm CST MSDS Number: M00107 Chemical Name: Dithionous acid, disodium salt CAS Number: 7775-14-6 Additional CAS No. (for hydrated forms): Not applicable Chemical Formula: Na2S2O4 Chemical Family: Reducing Agent Intended Use: Laboratory Use _____________________________________________________________________________ 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION GHS Classification: Hazard categories: Self Heating: Self-heat. 1 Acute Toxicity: Acute Tox. 4-Orl . Serious Eye Damage/Eye Irritation:Eye Irrit. 2 Specific Target Organ Toxicity - Single Exposure: STOT SE 3 Hazardous to the Aquatic Environment: Aquatic Chronic 3 GHS Label Elements: DANGER Hazard statements: Self-heating: maycatch fire. Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. Harmful to aquatic life with long lasting effects. Precautionary statements: Avoid breathing dust/fume/gas/mist/vapours/spray. Handle environmental release according to local, state, federal, provincial requirements. Wear eye protection. IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice/attention. IF INHALED: Remove victim/person to fresh air and keep at rest in a position comfortable for breathing. Call a POISON CENTER or doctor/physician if you feel unwell. IF SWALLOWED: Call a POISON CENTER or doctor/physician if you feel unwell. -

Mechanisms of Anaerobic Nitric Oxide Detoxification by Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium

Mechanisms of anaerobic nitric oxide detoxification by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Anke Arkenberg Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences, University of East Anglia September 2013 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisory team of Gary Rowley, David Richardson and Margaret Wexler. Their guidance and support has allowed me to finish this thesis despite starting full-time work after the third year. Also, I am grateful to my parents as without their emotional and financial support this would not have been possible. Mama und Papa, ich danke Euch von ganzem Herzen, dass Ihr soviel Vertrauen in mich gesetzt, mich die ganze Zeit voll und ganz unterstützt habt und hoffe, dass es die Investition wert war. Huge thanks go to Luke, my financé, who has supported and motivated me throughout, but especially throughout the endeavour of working full-time and continuing the thesis work in the remaining time: You have carried me through the highs and lows and helped me to stay focused! Thanks also to my friends Connie, Eileen, Hannah, Hayley, Sarah: Meeting up at the office or elsewhere, eating some home-baked goodies, going for a run around the lake, and being able to forget the long lab hours has kept me positive and sane. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride