Kumbharia: the Neminatha Temple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism & Jainism in Early Historic Asia Iconography of Parshvanatha

Buddhism & Jainism in Early Historic Asia Iconography of Parshvanatha at Annigere in North Karnataka – An Analysis Dr. Soumya Manjunath Chavan* India being the country which is known to have produced three major religions of the world: Hinduism, Budhism and Jainism. Jainism is still a practicing religion in many states of India like Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. The name Jaina is derived from the word jina, meaning conqueror, or liberator. Believing in immortal and indestructible soul (jiva) within every living being, it’s final goal is the state of liberation known as kaivalya, moksha or nirvana. The sramana movements rose in India in circa 550 B.C. Jainism in Karnataka began with the stable connection of the Digambara monk called Simhanandi who is credited with the establishment of the Ganga dynasty around 265 A.D. and thereafter for almost seven centuries Jain communities in Karnataka enjoyed the continuous patronage of this dynasty. Chamundaraya, a Ganga general commissioned the colossal rock- hewn statue of Bahubali at Sravana Belagola in 948 which is the holiest Jain shrines today. Gangas in the South Mysore and Kadambas and Badami Chalukyans in North Karnataka contributed to Jaina Art and Architecture. The Jinas or Thirthankaras list to twenty-four given before the beginning of the Christian era and the earliest reference occurs in the Samavayanga Sutra, Bhagavati Sutra, Kalpasutra and Pumacariyam. The Kalpasutra describes at length only the lives of Rishabhanatha, Neminatha, Parshvanatha and Mahavira. The iconographic feature of Parsvanatha was finalised first with seven-headed snake canopy in the first century B.C. -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

Impact Factor 3.025

AayushiImpact International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) Factor UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 ISSN 2349-638x Vol - IV 3Issue.025-XII DECEMBER 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 Refereed And Indexed Journal AAYUSHI INTERNATIONAL INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Monthly Journal VOL-IV ISSUE-XII Dec. 2017 •Vikram Nagar, Boudhi Chouk, Latur. Address •Tq. Latur, Dis. Latur 413512 (MS.) •(+91) 9922455749, (+91) 8999250451 •[email protected] Email •[email protected] Website •www.aiirjournal.com Email id’s:- [email protected] EDITOR,[email protected] – PRAMOD PRAKASHRAO I Mob.08999250451 TANDALE Page website :- www.aiirjournal.com l UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 No. 121 Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - IV Issue-XII DECEMBER 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 Jain Centres In Chikodi Taluka Dr. S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept. of A.I.Histoty and Epi. K.U.D. Dharwad Email ID: [email protected] Jainism is one of the earliest religions in Chikodi taluka. Jainisim made its entry in the pre- Christian era. Inscriptions revealed that Jaina saints came to preach the doctrines of the religion in about 225 B.C.1 Jainism was a very popular religion from 4th to 13th century because many dynasties of this period belonged to Jainism and it declined subsequently due to spread of Shaivism and Veerashaivism.Many Jinalayas were converted into Shaivalayas, Vaishanvalayas and Gramadevi temples. For instance, one Adinatha basati built by Kamalapure family of Kabbur was converted into Shaiva temple. As records were destroyed, it is very difficult to recognize it as basati.2 Six percent of Jains are found in this region. -

Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Traditions Dr

1 Nonviolence in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions Dr. Vincent Sekhar, SJ Arrupe Illam Arul Anandar College Karumathur – 625514 Madurai Dt. INDIA E-mail: [email protected] Introduction: Religion is a human institution that makes sense to human life and society as it is situated in a specific human context. It operates from ultimate perspectives, in terms of meaning and goal of life. Religion does not merely provide a set of beliefs, but offers at the level of behaviour certain principles by which the believing community seeks to reach the proposed goals and ideals. One of the tasks of religion is to orient life and the common good of humanity, etc. In history, religion and society have shaped each other. Society with its cultural and other changes do affect the external structure of any religion. And accordingly, there might be adaptations, even renewals. For instance, religions like Buddhism and Christianity had adapted local cultural and traditional elements into their religious rituals and practices. But the basic outlook of Buddhism or Christianity has not changed. Their central figures, tenets and adherence to their precepts, etc. have by and large remained the same down the history. There is a basic ethos in the religious traditions of India, in Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism. Buddhism may not believe in a permanent entity called the Soul (Atman), but it believes in the Act (karma), the prime cause for the wells or the ills of this world and of human beings. 1 Indian religions uphold the sanctity of life in all its forms and urge its protection. -

JAINISM Early History

111111xxx00010.1177/1111111111111111 Copyright © 2012 SAGE Publications. Not for sale, reproduction, or distribution. J Early History JAINISM The origins of the doctrine of the Jinas are obscure. Jainism (Jinism), one of the oldest surviving reli- According to tradition, the religion has no founder. gious traditions of the world, with a focus on It is taught by 24 omniscient prophets, in every asceticism and salvation for the few, was confined half-cycle of the eternal wheel of time. Around the to the Indian subcontinent until the 19th century. fourth century BCE, according to modern research, It now projects itself globally as a solution to the last prophet of our epoch in world his- world problems for all. The main offering to mod- tory, Prince Vardhamāna—known by his epithets ern global society is a refashioned form of the Jain mahāvīra (“great hero”), tīrthaṅkāra (“builder of ethics of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and nonpossession a ford” [across the ocean of suffering]), or jina (aparigraha) promoted by a philosophy of non- (spiritual “victor” [over attachment and karmic one-sidedness (anekāntavāda). bondage])—renounced the world, gained enlight- The recent transformation of Jainism from an enment (kevala-jñāna), and henceforth propagated ideology of world renunciation into an ideology a universal doctrine of individual salvation (mokṣa) for world transformation is not unprecedented. It of the soul (ātman or jīva) from the karmic cycles belongs to the global movement of religious mod- of rebirth and redeath (saṃsāra). In contrast ernism, a 19th-century theological response to the to the dominant sacrificial practices of Vedic ideas of the European Enlightenment, which West- Brahmanism, his method of salvation was based on ernized elites in South Asia embraced under the the practice of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and asceticism influence of colonialism, global industrial capital- (tapas). -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

VII STD Social Science Term 3 History Chapter 1 New Religious Ideas and Movements

NEW BHARATH MATRICULATION HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL,TVR VII STD Social Science Term 3 History Chapter 1 New Religious Ideas and Movements I. Choose the correct answer: Question 1. Who of the following composed songs on Krishna putting himself in the place of mother Yashoda? (a) Poigaiazhwar (b) Periyazhwar (c) Nammazhwar (d) Andal Answer: (b) Periyazhwar Question 2. Who preached the Advaita philosophy? (a) Ramanujar (b) Ramananda (c) Nammazhwar (d) Adi Shankara Answer: (d) Adi Shankara Question 3. Who spread the Bhakthi ideology in northern India and made it a mass movement? (a) Vallabhacharya (b) Ramanujar (c) Ramananda (d) Surdas Answer: (c) Ramananda Question 4. Who made Chishti order popular in India? (a) Moinuddin Chishti (b) Suhrawardi (c) Amir Khusru (d) Nizamuddin Auliya Answer: (a) Moinuddin Chishti Question 5. Who is considered their first guru by the Sikhs? (a) Lehna (b) Guru Amir Singh (c) GuruNanak (d) Guru Gobind Singh Answer: (c) GuruNanak II. Fill in the Blanks. 1. Periyazhwar was earlier known as ______ 2. ______ is the holy book of the Sikhs. 3. Meerabai was the disciple of ______ 4. philosophy is known as Vishistadvaita ______ 5. Gurudwara Darbar Sahib is situated at ______ in Pakistan. Answer: 1. Vishnu Chittar 2. Guru Granth Sahib 3. Ravi das 4. Ramanuja’s 5. Karatarpur III. Match the following. Pahul – Kabir Ramcharitmanas – Sikhs Srivaishnavism – Abdul-Wahid Abu Najib Granthavali – Guru Gobind Singh Suhrawardi – Tulsidas Answer: Pahul – Sikhs Ramcharitmanas – Tulsidas Srivaishnavism – Ramanuja Granthavali – Kabir Suhrawardi – Abdul-Wahid Abu Najib IV. Find out the right pair/pairs: (1) Andal – Srivilliputhur (2) Tukaram – Bengal (3) Chaitanyadeva – Maharashtra (4) Brahma-sutra – Vallabacharya (5) Gurudwaras – Sikhs Answer: (1) Andal – Srivilliputhur (5) Gurudwaras – Sikhs Question 2. -

Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi's in Jainism

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 616-618 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi’s in Jainism IJAR 2016; 2(2): 616-618 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 13-12-2015 Dr. Venkatesha TS Accepted: 15-01-2016 Jainism, one of the oldest living faiths of India, has a hoary antiquity in Karnataka. No doubt, Dr. Venkatesha TS UGC-POST Doctoral Fellow this religion took its birth in North India. However, within a couple of centuries of its birth, Department of Studies and this religionis said to have entered into Karnataka. Jaina tradition ascribes III C.B.C. as the Research in History and date of entry of this religion to south India, and in particular to Karnataka. After this period Archaeology Tumkur Jainism grew from strength to strength and heralded a glorious era, never to be witnessed in University, Tumkur-572103 any part of India, to become a religion next only to Brahmanism in popularity and number. Though Jainism was spread over different parts of south India within the first few centuries of the Christian era, its nucleus as well as the stronghold was southern Karnataka. In fact, it is the general opinion that the history of Jainism in south India is predominantly the history of that religion in Karnataka. Such was the prominence that this religion enjoyed throughout the first millennium A.D. Liberal royal patronage extended by the Kadambas, the Gangas, the Chalukyas of Badami, the Rashtrakutas, the Nolambas, the Kalyana Chalukyas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar rulers and their successors, resulted in the uninterrupted growth of this religion in southern Karnataka. -

The Heart of Jainism

;c\j -co THE RELIGIOUS QUEST OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, MA. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG MEN S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON AND H. D. GRISWOLD, MA., PH.D. SECRETARY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONS IN INDIA si 7 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME ALREADY PUBLISHED INDIAN THEISM, FROM By NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., THE VEDIC TO THE D.Litt. Pp.xvi + 292. Price MUHAMMADAN 6s. net. PERIOD. IN PREPARATION THE RELIGIOUS LITERA By J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A. TURE OF INDIA. THE RELIGION OF THE By H. D. GRISWOLD, M.A., RIGVEDA. PH.D. THE VEDANTA By A. G. HOGG, M.A., Chris tian College, Madras. HINDU ETHICS By JOHN MCKENZIE, M.A., Wilson College, Bombay. BUDDHISM By K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. ISLAM IN INDIA By H. A. WALTER, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. JAN 9 1986 EDITORIAL PREFACE THE writers of this series of volumes on the variant forms of religious life in India are governed in their work by two impelling motives. I. They endeavour to work in the sincere and sympathetic spirit of science. They desire to understand the perplexingly involved developments of thought and life in India and dis passionately to estimate their value. They recognize the futility of any such attempt to understand and evaluate, unless it is grounded in a thorough historical study of the phenomena investigated. In recognizing this fact they do no more than share what is common ground among all modern students of religion of any repute. -

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Dr Jagraj Singh A publication of Sikh University USA Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 1 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A comparative study of Sikhism and Hinduism Contents Page Acknowledgements 4 Foreword Introduction 5 Chapter 1 What is Sikhism? 9 What is Hinduism? 29 Who are Sikhs? 30 Who are Hindus? 33 Who is a Sikh? 34 Who is a Hindu? 35 Chapter 2 God in Sikhism. 48 God in Hinduism. 49 Chapter 3 Theory of creation of universe---Cosmology according to Sikhism. 58 Theory of creation according to Hinduism 62 Chapter 4 Scriptures of Sikhism 64 Scriptures of Hinduism 66 Chapter 5 Sikh place of worship and worship in Sikhism 73 Hindu place of worship and worship in Hinduism 75 Sign of invocation used in Hinduism Sign of invocation used in Sikhism Chapter 6 Hindu Ritualism (Karm Kanda) and Sikh view 76 Chapter 7 Important places of Hindu pilgrimage in India 94 Chapter 8 Hindu Festivals 95 Sikh Festivals Chapter 9 Philosophy of Hinduism---Khat Darsan 98 Philosophy of Sikhism-----Gur Darshan / Gurmat 99 Chapter 10 Panjabi language 103 Chapter 11 The devisive caste system of Hinduism and its rejection by Sikhism 111 Chapter 12 Religion and Character in Sikhism------Ethics of Sikhism 115 Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 2 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Sexual morality in Sikhism Sexual morality in Hinduism Religion and ethics of Hinduism Status of woman in Hinduism Chapter13 Various concepts of Hinduism and the Sikh view 127 Chapter 14 Rejection of authority of scriptures of Hinduism by Sikhism 133 Chapter 15 Sacraments of Hinduism and Sikh view 135 Chapter 16 Yoga (Yogic Philosophy of Hinduism and its rejection in Sikhism 142 Chapter 17 Hindu mythology and Sikh view 145 Chapter 18 Un-Sikh and anti-Sikh practices and their rejection 147 Chapter 19 Sikhism versus other religious aystems 149 Glossary of common terms used in Sikhism 154 Bibliography 160 Copyright Dr. -

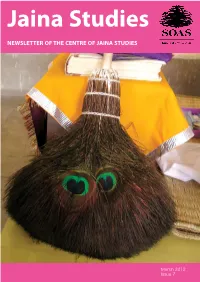

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P.