En-Gendering Economic Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diane Perrons Gendering the Inequality Debate

Diane Perrons Gendering the inequality debate Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Perrons, Diane (2015) Gendering the inequality debate. Gender and Development, 23 (2). pp. 207-222. ISSN 1355-2074 DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2015.1053217 © 2015 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63415/ Available in LSE Research Online: September 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Gendering the inequality debate Diane Perrons In the past 30 years, economic inequality has increased to unprecedented levels, and is generating widespread public concern amongst orthodox, as well as leftist and feminist thinkers. This article explores the gender dimensions of growing economic inequality, summarises key arguments from feminist economics which expose the inadequacy of current mainstream economic analysis on which ‘development’ is based, and argues for a ‘gender and equality’ approach to economic and social policy in both the global North and South. -

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010 Contract negotiations, management and meeting arrangements for ASSA meetings are conducted by the American Economic Association. i ASSA_Program.indb 1 11/17/09 7:45 AM Thanks to the 2010 American Economic Association Program Committee Members Robert Hall, Chair Pol Antras Ravi Bansal Christian Broda Charles Calomiris David Card Raj Chetty Jonathan Eaton Jonathan Gruber Eric Hanushek Samuel Kortum Marc Melitz Dale Mortensen Aviv Nevo Valerie Ramey Dani Rodrik David Scharfstein Suzanne Scotchmer Fiona Scott-Morton Christopher Udry Kenneth West Cover Art is by Tracey Ashenfelter, daughter of Orley Ashenfelter, Princeton University, former editor of the American Economic Review and President-elect of the AEA for 2010. ii ASSA_Program.indb 2 11/17/09 7:45 AM Contents General Information . .iv Hotels and Meeting Rooms ......................... ix Listing of Advertisers and Exhibitors ................xxiv Allied Social Science Associations ................. xxvi Summary of Sessions by Organization .............. xxix Daily Program of Events ............................ 1 Program of Sessions Saturday, January 2 ......................... 25 Sunday, January 3 .......................... 26 Monday, January 4 . 122 Tuesday, January 5 . 227 Subject Area Index . 293 Index of Participants . 296 iii ASSA_Program.indb 3 11/17/09 7:45 AM General Information PROGRAM SCHEDULES A listing of sessions where papers will be presented and another covering activities such as business meetings and receptions are provided in this program. Admittance is limited to those wearing badges. Each listing is arranged chronologically by date and time of the activity; the hotel and room location for each session and function are indicated. CONVENTION FACILITIES Eighteen hotels are being used for all housing. -

While Thomas Piketty's Bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Review of Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay, Demeter Press 2014 in Morgenbladet, Norway 4-10 July 20014 While Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. Maria Berg Reinertsen, Economics commentator in Morgenbladet, Norway The article translated: Should breastmilk be included in gross domestic product? Maria Berg Reinertsen Morgenbladet, Norway 4.July 2014 [Translated from Norwegian] We run into one of my former university professors, and I take the opportunity to expand the three-year old’s knowledge of occupations beyond firefighter and barista. "This man is doing research on money ..." "No, no," protests the professor, "not money ..." "Sorry. This man is doing research on the real economy. " The three year old is unperturbed: "That man is very tall." But the correction is important. Economists will not settle for counting money and millions, they will say something about what is happening in the real economy. But where are the limits of it? The most underestimated economic book this spring is perhaps the anthology Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay. Waring is a pioneer in feminist economics, and while Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. -

Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market

Schymik, Jan: Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Munich Discussion Paper No. 2017- Department of Economics University of Munich Volkswirtschaftliche Fakultät Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Online at https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.38385 Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Jan Schymik Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich May 2017 Abstract Many industrialized economies have seen a rapid rise in top income inequality and in the globalization of production since the 1980s. In this paper I propose an open economy model of executive pay to study how offshoring affects the pay level and incentives of top earners. The model introduces a simple principal-agent problem into a heterogeneous firm talent assignment model and endogenizes pay levels and the sensitivity of pay to performance in general equilibrium. Using unique data of manager-firm matches including executives from stock market listed firms across the U.S. and Europe, I quantify the model predictions empirically. Overall, I find that between 2000 and 2014 offshoring has increased executive pay levels, raised earnings inequality across executives and increased the sensitivity of pay to firm performance. JEL Classification: D2,F1,F2,J3,L2 Keywords: Offshoring; Earnings Structure, Inequality; Incentives; Executive Com- pensation Department of Economics, LMU Munich, E-mail: [email protected] I am particularly grateful to Daniel Baumgarten, David Dorn, Carsten Eckel, Florian Englmaier, Maria Guadalupe, Dalia Marin and conference audiences at the MGSE Colloquium, DFG SPP 1764 Conference IAB Nuremberg 2015 and EARIE Munich 2015 for their valuable comments. -

TIWARI-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf

Copyright by Bhavya Tiwari 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Bhavya Tiwari Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South Committee: Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, Supervisor David Damrosch Martha Ann Selby Cesar Salgado Hannah Wojciehowski Beyond English: Translating Modernism in the Global South by Bhavya Tiwari, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 Dedication ~ For my mother ~ Acknowledgements Nothing is ever accomplished alone. This project would not have been possible without the organic support of my committee. I am specifically thankful to my supervisor, Elizabeth Richmond-Garza, for giving me the freedom to explore ideas at my own pace, and for reminding me to pause when my thoughts would become restless. A pause is as important as movement in the journey of a thought. I am thankful to Martha Ann Selby for suggesting me to subhead sections in the dissertation. What a world of difference subheadings make! I am grateful for all the conversations I had with Cesar Salgado in our classes on Transcolonial Joyce, Literary Theory, and beyond. I am also very thankful to Michael Johnson and Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski for patiently listening to me in Boston and Austin over luncheons and dinners respectively. I am forever indebted to David Damrosch for continuing to read all my drafts since February 2007. I am very glad that our paths crossed in Kali’s Kolkata. -

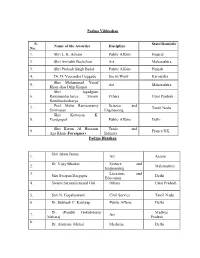

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

The Laws of Capitalism (Book Review)

BOOK REVIEW THE LAWS OF CAPITALISM CAPITAL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY. By Thomas Piketty. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2014. Pp. 685. $39.95. Reviewed by David Singh Grewal* I. CAPITALISM TODAY The past year has seen the surprising ascent of French economist Thomas Piketty to "rock star" status. 1 The reading public's appetite for his economic treatise seems motivated by a growing unease about economic inequality and an anxiety that the "Great Recession," which followed the financial crisis of 2008, defines a new economic normal. The seemingly plutocratic response to the crisis has become the focus of angry attacks by protesters on both left and right,2 but their criti cisms have had little practical effect, even while subsequent events have confirmed their fears. In 2oro, the United States Supreme Court sealed the union of corporate money and politics in Citizens United v. FEC,3 which subsequent judgments have further entrenched.4 Mean while, the response to the crisis in Europe has suggested that Brussels now operates as an arm of finance capital and that monetary union is more likely to prove the undertaker of European social democracy than its savior. 5 * Associate Professor, Yale Law School. The author thanks Ruth Abbey, Bruce Ackerman, Cliff Ando, Rick Brooks, Angus Burgin, Daniela Cammack, Paul Cammack, Stefan Eich, Owen Fiss, Bryan Garsten, Arthur Goldhammer, Jacob Hacker, Robert Hockett, Paul Kahn, Amy Kapczynski, Jeremy Kessler, Alvin Klevorick, Jonathan Macey, Daniel Markovits, Pratap Mehta, Robert Post, Jedediah Purdy, Sanjay Reddy, Roberta Romano, George Scialabba, Tim Shenk, Reva Siegel, Peter Spiegler, Adam Tooze, Richard Tuck, Patrick Weil, and John Witt for discus sions on these and related issues. -

Organization Studies of Inequality, with and Beyond Piketty

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty Citation for published version: Dunne, S, Grady, J & Weir, K 2018, 'Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty', Organization, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 165-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417714535 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/1350508417714535 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Organization Publisher Rights Statement: Copyright © 2018, © SAGE Publications General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Final accepted peer reviewed manuscript by Weir, K., Grady, J., and Dunne, S. accepted in Organization, 2017. Organization Studies of Inequality, with and beyond Piketty ABSTRACT Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century did much to bring discussions of economic inequality into the intellectual and popular mainstream. This paper indicates how business, management and organization studies can productively engage with Cap21st. It does this by deriving practical consequences from Piketty’s proposed division of intellectual labour in general and his account of ‘supermanagers’ in particular. -

![Vf/Klwpukwww Ubz Fnyyh] 8 Vizsy] 2015 Laaaa](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2764/vf-klwpukwww-ubz-fnyyh-8-vizsy-2015-laaaa-822764.webp)

Vf/Klwpukwww Ubz Fnyyh] 8 Vizsy] 2015 Laaaa

jftLVªh laö Mhö ,yö&33004@99 REGD. NO. D. L.-33004/99 vlk/kj.k EXTRAORDINARY Hkkx I—[k.M 1 PART I—Section 1 izkf/dkj ls izdkf'kr PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY la- 83] ubZ fnYyh] cq/okj] vçSy 8] 2015@pS=k 18] 1937 No. 83] NEW DELHI, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 8, 2015/CHAITRA 18, 1937 jk”Vªifr lfpoky; vf/vf/vf/kvf/ kkklwpuklwpuk ubZ fnYyh] 8 vizSy] 2015 lalala-la--- 35&izst@201535&izst@2015----&&&&Hkkjr ds jk”Vªifr fuEufyf[kr in~e iqjLdkj lg”kZ iznku djrs gSa %& in~e foHkw”k.k 1- Jh vferkHk cPpu] dyk] egkjk”Vª A 2- Jh /keZLFky ohjsUnz gsXxMs] lekt lsok] dukZVd A 3- egkefge ‘kgtknk djhe vkxk [kku] lekt lsok] Ýkal A 4- Jh eksgEen ;qlwQ [kku mQZ fnyhi dqekj] dyk] egkjk”Vª A 5- izks- ewywj jkeLokfe Jhfuoklu] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] rfeyukMq A 6- Jh ds- ds- os.kqxksiky] yksddk;Z] fnYyh A in~e Hkw”k.k 1- Jh tkg~uw c#vk] dyk] vle A 2- izks- e×ktqy HkkxZo] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] ;q-,l-,- A 3- MkW- fot; HkVdj] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] egkjk”Vª A 4- Lokeh lR;fe=kuUn fxfj] vk/;kfRed f’k{kk] mRrjk[kaM A 5- MkW- lqHkk”k dk’;i] yksddk;Z] fnYyh A 6- MkW- if.Mr xksdqyksRloth egkjkt] dyk] e/; izns’k A 1599 GI/2015 (1) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [P ART I—SEC . 1] 7- MkW- vEcjh’k feRFky] fpfdRlk] fnYyh A 8- Jh f’kodqekj Lokfexyq] vk/;kfRed f’k{kk] dukZVd A in~e Jh 1- Jhefr lck vatqe] [ksy] NRrhlx<+ A 2- Jh ,l- v:.ku] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] dukZVd A 3- MkW- csRrhuk ‘kkjnk ckSej] lkfgR; ,oa f’k{kk] fgekpy izns’k A 4- Jh v’kksd Hkxr] lekt lsok] >kj[kaM A 5- izks- tWd Cykeksa] foKku ,oa baftfu;jh] Ýkal A 6- izks- ¼MkW-½ y{eh uUnu cjk] lkfgR; ,oa f’k{kk] vle A 7- MkW- ;ksxs’k -

A Review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Journal of Economic Literature 2014, 52(2), 519–534 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.2.519 The Return of “Patrimonial Capitalism”: A Review of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century † Branko Milanovic * Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty provides a unified theory of the functioning of the capitalist economy by linking theories of economic growth and functional and personal income distributions. It argues, based on the long-run historical data series, that the forces of economic divergence (including rising income inequality) tend to dominate in capitalism. It regards the twentieth century as an exception to this rule and proposes policies that would make capitalism sustainable in the twenty-first century. ( JEL D31, D33, E25, N10, N30, P16) 1. Introduction state that we are in the presence of one of the watershed books in economic thinking. am hesitant to call Thomas Piketty’s new Piketty is mostly known as a researcher I book Capital in the Twenty-First Century of income inequality. His book Les hauts (Le capital au XXI e siècle in the French revenus en France au XXe siècle: Inégalités original) one of the best books on economics et redistributions, 1901–1998, published in written in the past several decades. Not that 2001, was the basis for several influential I do not believe it is, but I am careful because papers published in the leading American of the inflation of positive book reviews and economic journals. In the book, Piketty because contemporaries are often poor documented, using fiscal sources, the rise judges of what may ultimately prove to be (until the World War I), the fall (between influential. -

An Agency Theory of Dividend Taxation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES AN AGENCY THEORY OF DIVIDEND TAXATION Raj Chetty Emmanuel Saez Working Paper 13538 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13538 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2007 We thank Alan Auerbach, Martin Feldstein, Roger Gordon, Kevin Hassett, James Poterba, and numerous seminar participants for very helpful comments. Joseph Rosenberg and Ity Shurtz provided outstanding research assistance. Financial support from National Science Foundation grants SES-0134946 and SES-0452605 is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2007 by Raj Chetty and Emmanuel Saez. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. An Agency Theory of Dividend Taxation Raj Chetty and Emmanuel Saez NBER Working Paper No. 13538 October 2007 JEL No. G3,H20 ABSTRACT Recent empirical studies of dividend taxation have found that: (1) dividend tax cuts cause large, immediate increases in dividend payouts, and (2) the increases are driven by firms with high levels of shareownership among top executives or the board of directors. These findings are inconsistent with existing "old view" and "new view" theories of dividend taxation. We propose a simple alternative theory of dividend taxation in which managers and shareholders have conflicting interests, and show that it can explain the evidence. Using this agency model, we develop an empirically implementable formula for the efficiency cost of dividend taxation. -

The Poverty Puzzle

THE POVERTY PUZZLE TIMESFREEPRESS.COM / POVERTYPUZZLE PUBLISHED MARCH 6, 2016 EDITOR’S NOTE n 2015, the Chatta- hood that has seen better times. And we see nooga Times Free panhandlers with cardboard signs standing Press poured an un- at intersections seeking a handout. But we precedented amount quickly forget, lost in our own lives. of time and energy Truth is, poverty usually doesn’t directly I into researching affect most of us unless someone we know the roots of and (maybe us) is laid off and finds it hard to solutions to Chat- land another job. Or perhaps someone in tanooga’s economic our family is hard hit by medical expenses reality; we made this investment as other re- and faces not having enough money, too gional news outlets were pulling back from many bills and a genuine fear of losing our long-term reporting projects. home. Suddenly, poverty becomes very real. Initially, the idea behind The Poverty In our reporting, we discovered that our Puzzle series was fairly cliché: the tale of region, state and city are being crippled by two cities. Chattanooga had been getting powerful forces that aren’t being discussed a significant amount of positive attention publicly. Chattanooga can certainly boast nationally, but on the ground, our reporters about its good numbers: lower unemploy- saw another story unfolding. ment, job growth in high-paying fields, low After the Great Recession, poverty in- taxes and relatively low cost of living. But creased among all ethnic groups in the city, its there are other numbers and cutting-edge outlying suburbs, the rural pockets of Hamil- research being ignored that will matter greatly ton County and the greater metro area.