Is There a Global Super‐Bourgeoisie?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diane Perrons Gendering the Inequality Debate

Diane Perrons Gendering the inequality debate Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Perrons, Diane (2015) Gendering the inequality debate. Gender and Development, 23 (2). pp. 207-222. ISSN 1355-2074 DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2015.1053217 © 2015 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63415/ Available in LSE Research Online: September 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Gendering the inequality debate Diane Perrons In the past 30 years, economic inequality has increased to unprecedented levels, and is generating widespread public concern amongst orthodox, as well as leftist and feminist thinkers. This article explores the gender dimensions of growing economic inequality, summarises key arguments from feminist economics which expose the inadequacy of current mainstream economic analysis on which ‘development’ is based, and argues for a ‘gender and equality’ approach to economic and social policy in both the global North and South. -

Social-Class-Hidden-Rules-Quiz.Pdf

Action 2 Hidden Rules Could You Survive in Poverty? Put a check by each item you know how to do. ___ 1. I know which churches and sections of town have the best rummage sales. ___ 2. I know when Walmart, drug stores, and convenience stores throw away over-the-counter medicine with expired dates. ___ 3. I know which pawn shops sell DVDs for $1. ___ 4. In my town in criminal courts, I know which judges are lenient, which ones are crooked, and which ones are fair. ___ 5. I know how to physically fi ght and defend myself physically. ___ 6. I know how to get a gun, even if I have a police record. ___ 7. I know how to keep my clothes from being stolen at the Laundromat. ___ 8. I know what problems to look for in a used car. ___ 9. I/my family use a payday lender. ___ 10. I know how to live without electricity and a phone. ___ 11. I know how to use a knife as scissors. ___ 12. I can entertain a group of friends with my personality and my stories. ___ 13. I know which churches will provide assistance with food or shelter. Students Educate 10 Actions to ___ 14. I know how to move in half a day. ___ 15. I know how to get and use food stamps or an electronic card for benefi ts. ___ 16. I know where the free medical clinics are. ___ 17. I am very good at trading and bartering. -

While Thomas Piketty's Bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Review of Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay, Demeter Press 2014 in Morgenbladet, Norway 4-10 July 20014 While Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. Maria Berg Reinertsen, Economics commentator in Morgenbladet, Norway The article translated: Should breastmilk be included in gross domestic product? Maria Berg Reinertsen Morgenbladet, Norway 4.July 2014 [Translated from Norwegian] We run into one of my former university professors, and I take the opportunity to expand the three-year old’s knowledge of occupations beyond firefighter and barista. "This man is doing research on money ..." "No, no," protests the professor, "not money ..." "Sorry. This man is doing research on the real economy. " The three year old is unperturbed: "That man is very tall." But the correction is important. Economists will not settle for counting money and millions, they will say something about what is happening in the real economy. But where are the limits of it? The most underestimated economic book this spring is perhaps the anthology Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay. Waring is a pioneer in feminist economics, and while Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. -

Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market

Schymik, Jan: Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Munich Discussion Paper No. 2017- Department of Economics University of Munich Volkswirtschaftliche Fakultät Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Online at https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.38385 Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Jan Schymik Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich May 2017 Abstract Many industrialized economies have seen a rapid rise in top income inequality and in the globalization of production since the 1980s. In this paper I propose an open economy model of executive pay to study how offshoring affects the pay level and incentives of top earners. The model introduces a simple principal-agent problem into a heterogeneous firm talent assignment model and endogenizes pay levels and the sensitivity of pay to performance in general equilibrium. Using unique data of manager-firm matches including executives from stock market listed firms across the U.S. and Europe, I quantify the model predictions empirically. Overall, I find that between 2000 and 2014 offshoring has increased executive pay levels, raised earnings inequality across executives and increased the sensitivity of pay to firm performance. JEL Classification: D2,F1,F2,J3,L2 Keywords: Offshoring; Earnings Structure, Inequality; Incentives; Executive Com- pensation Department of Economics, LMU Munich, E-mail: [email protected] I am particularly grateful to Daniel Baumgarten, David Dorn, Carsten Eckel, Florian Englmaier, Maria Guadalupe, Dalia Marin and conference audiences at the MGSE Colloquium, DFG SPP 1764 Conference IAB Nuremberg 2015 and EARIE Munich 2015 for their valuable comments. -

The Laws of Capitalism (Book Review)

BOOK REVIEW THE LAWS OF CAPITALISM CAPITAL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY. By Thomas Piketty. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2014. Pp. 685. $39.95. Reviewed by David Singh Grewal* I. CAPITALISM TODAY The past year has seen the surprising ascent of French economist Thomas Piketty to "rock star" status. 1 The reading public's appetite for his economic treatise seems motivated by a growing unease about economic inequality and an anxiety that the "Great Recession," which followed the financial crisis of 2008, defines a new economic normal. The seemingly plutocratic response to the crisis has become the focus of angry attacks by protesters on both left and right,2 but their criti cisms have had little practical effect, even while subsequent events have confirmed their fears. In 2oro, the United States Supreme Court sealed the union of corporate money and politics in Citizens United v. FEC,3 which subsequent judgments have further entrenched.4 Mean while, the response to the crisis in Europe has suggested that Brussels now operates as an arm of finance capital and that monetary union is more likely to prove the undertaker of European social democracy than its savior. 5 * Associate Professor, Yale Law School. The author thanks Ruth Abbey, Bruce Ackerman, Cliff Ando, Rick Brooks, Angus Burgin, Daniela Cammack, Paul Cammack, Stefan Eich, Owen Fiss, Bryan Garsten, Arthur Goldhammer, Jacob Hacker, Robert Hockett, Paul Kahn, Amy Kapczynski, Jeremy Kessler, Alvin Klevorick, Jonathan Macey, Daniel Markovits, Pratap Mehta, Robert Post, Jedediah Purdy, Sanjay Reddy, Roberta Romano, George Scialabba, Tim Shenk, Reva Siegel, Peter Spiegler, Adam Tooze, Richard Tuck, Patrick Weil, and John Witt for discus sions on these and related issues. -

Organization Studies of Inequality, with and Beyond Piketty

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty Citation for published version: Dunne, S, Grady, J & Weir, K 2018, 'Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty', Organization, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 165-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417714535 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/1350508417714535 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Organization Publisher Rights Statement: Copyright © 2018, © SAGE Publications General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Final accepted peer reviewed manuscript by Weir, K., Grady, J., and Dunne, S. accepted in Organization, 2017. Organization Studies of Inequality, with and beyond Piketty ABSTRACT Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century did much to bring discussions of economic inequality into the intellectual and popular mainstream. This paper indicates how business, management and organization studies can productively engage with Cap21st. It does this by deriving practical consequences from Piketty’s proposed division of intellectual labour in general and his account of ‘supermanagers’ in particular. -

Who Rules Cincinnati?

Who Rules Cincinnati? A Study of Cincinnati’s Economic Power Structure And its Impact on Communities and People By Dan La Botz Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Published by Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Copyright ©2008 by Dan La Botz Table of Contents Summary......................................................................................................... 1 Preface.............................................................................................................4 Introduction.................................................................................................... 7 Part I - Corporate Power in Cincinnati.........................................................15 Part II - Corporate Power in the Media and Politics.....................................44 Part III - Corporate Power, Social Classes, and Communities......................55 Part IV - Cincinnati: One Hundred Years of Corporate Power.....................69 Discussion..................................................................................................... 85 Bibliography.................................................................................................. 91 Acknowledgments.........................................................................................96 About the Author...........................................................................................97 Summary This investigation into Cincinnati’s power structure finds that a handful of national and multinational corporations dominate -

A Review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Journal of Economic Literature 2014, 52(2), 519–534 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.2.519 The Return of “Patrimonial Capitalism”: A Review of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century † Branko Milanovic * Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty provides a unified theory of the functioning of the capitalist economy by linking theories of economic growth and functional and personal income distributions. It argues, based on the long-run historical data series, that the forces of economic divergence (including rising income inequality) tend to dominate in capitalism. It regards the twentieth century as an exception to this rule and proposes policies that would make capitalism sustainable in the twenty-first century. ( JEL D31, D33, E25, N10, N30, P16) 1. Introduction state that we are in the presence of one of the watershed books in economic thinking. am hesitant to call Thomas Piketty’s new Piketty is mostly known as a researcher I book Capital in the Twenty-First Century of income inequality. His book Les hauts (Le capital au XXI e siècle in the French revenus en France au XXe siècle: Inégalités original) one of the best books on economics et redistributions, 1901–1998, published in written in the past several decades. Not that 2001, was the basis for several influential I do not believe it is, but I am careful because papers published in the leading American of the inflation of positive book reviews and economic journals. In the book, Piketty because contemporaries are often poor documented, using fiscal sources, the rise judges of what may ultimately prove to be (until the World War I), the fall (between influential. -

Melissa S. Fisher WALL STREET WOMEN

Wall Street Women Melissa S. Fisher WALL STREET WOMEN Melissa S. Fisher Duke University Press Durham and London 2012 ∫ 2012 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Arno Pro by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. For my Bubbe, Rebecca Saidikoff Oshiver, and in the memory of my grandmother Esther Oshiver Fisher and my grandfather Mitchell Salem Fisher CONTENTS acknowledgments ix introduction Wall Street Women 1 1. Beginnings 27 2. Careers, Networks, and Mentors 66 3. Gendered Discourses of Finance 95 4. Women’s Politics and State-Market Feminism 120 5. Life after Wall Street 136 6. Market Feminism, Feminizing Markets, and the Financial Crisis 155 notes 175 bibliography 201 index 217 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A commitment to gender equality first brought about this book’s journey. My interest in understanding the transformations in women’s experiences in male-dominated professions began when I was a child in the seventies, listening to my grandmother tell me stories about her own experiences as one of the only women at the University of Penn- sylvania Law School in the twenties. I also remember hearing my mother, as I grew up, speaking about women’s rights, as well as visiting my father and grandfather at their law office in midtown Manhattan: there, while still in elementary school, I spoke to the sole female lawyer in the firm about her career. My interests in women and gender studies only grew during my time as an undergraduate at Barnard College. -

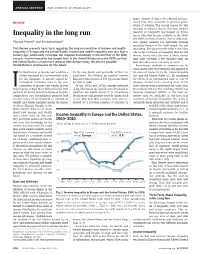

Inequality in the Long Run Survey Data That Became Available in the 1960S and 1970S in Many Countries

larger volumes of data to be collected and pro- REVIEW cessed than were accessible to previous gener- ations of scholars. The second reason for this time gap in using tax data is that most modern research on inequality has focused on micro- Inequality in the long run survey data that became available in the 1960s and 1970s in many countries. Survey data, how- 1 2 Thomas Piketty * and Emmanuel Saez ever, cannot measure top percentile incomes accurately because of the small sample size and This Review presents basic facts regarding the long-run evolution of income and wealth top coding. The top percentile plays a very large inequality in Europe and the United States. Income and wealth inequality was very high a role in the evolution of inequality that we will century ago, particularly in Europe, but dropped dramatically in the first half of the 20th discuss. Survey data also have a much shorter century. Income inequality has surged back in the United States since the 1970s so that time span—typically a few decades—than tax the United States is much more unequal than Europe today. We discuss possible data that often cover a century or more. interpretations and lessons for the future. Kuznets-type methods to construct top in- come shares were first extended and updated to he distribution of income and wealth is a for the top decile and percentile of the U.S. the cases of France (8, 9), the United Kingdom widely discussed and controversial topic. population. By dividing by national income, (10), and the United States (11). -

Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century: Global Inequality, Piketty, and the Transnational Capitalist Class

Chapter 13 Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century: Global Inequality, Piketty, and the Transnational Capitalist Class William I. Robinson Introduction Why has Thomas Piketty’s tome, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, sparked such a firestorm of debate on global inequalities in the world media, academic and policy circles? These inequalities are indeed truly savage. In 2015, the year after Piketty’s book was released in English,1 the development NGO Oxfam re- ported that the richest one percent of humanity would own more than the rest of the world in 2016.2 This is up from the one percent owning 44 percent of the world’s wealth in 2010 and 48 percent in 2014. If current trends continue, the one percent would own 54 percent by 2020. Even more shocking, the top 80 billionaires were worth $1.9 trillion in 2014, an amount equality to the bottom 50 percent of humanity and these 80 saw a 50 percent rise in their wealth in just four years. At the same time, the poorest 50 percent saw a drop in their wealth during this same four-year period from 2010 to 2014. In other words, there has been a huge transfer of wealth in a very short period of time from the poorest half of humanity to the richest 80 individuals on the planet. I do not think however, that outrage over these inequalities explains the attention that Piketty’s study has received. After all, Piketty is far from the first to draw attention to such expanding inequalities in recent years and he does not even show just how pronounced they are in the same way that Oxfam and other studies have done so. -

Bridges out of Poverty

Bridges out of Poverty Session 1 of 3 June 16, 2021 Kiersten Baer • Online MarketingCoordinator • Illinois Center for Specialized Professional Support • [email protected] • 309-438-1838 Where is Your Local Area? Title I Job Corps Adult Ed Second Wagner Chance Peyser Which partner do you Youth Voc Rehab best represent? Build Chief Elected Official One stop SCSEP partners CTE Board Member Migrant TANF Farmworker s Business HUD TAA CSBG UI Veterans Melissa Martin • Mmartincommunication.com • [email protected] • 307-214-2702 Agenda Three-Part Series • Session 1 - 6/16/2021, 10 – 11:30 a.m. • Participants will explore the mental models for each social class and how perceptions shape actions. • Session 2 – 6/23/2021, 1 – 2:30 p.m. • Building on the previous session, participants will explore the research centered around poverty in their area, as well as explore the hidden rules that exist in the 3 socioeconomic classes. • Session 3 – 6-30-2021, 10 – 11:30 p.m. • Building on the previous 2 sessions, participants will begin to apply the material through the awareness of language use and differing resources. BRIDGES out of Poverty Copyright 2006. Revised 2017. All rights reserved. aha! Process, Inc. www.ahaprocess.com @ahaprocess 7 Copyright 2006. Revised 2017. All rights reserved. aha! Process, Inc. www.ahaprocess.com @ahaprocess 8 PHILANTHROPY, POLICY, QUALITY OF LIFE Copyright 2006. Revised 2017. All rights reserved. aha! Process, Inc. www.ahaprocess.com @ahaprocess 9 Could you Survive? Poverty? Middle Class? Wealth? Copyright 2006. Revised 2017. All rights reserved. aha! Process, Inc. www.ahaprocess.com @ahaprocess 10 KEY POINT Generational and situational poverty are different.