Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diane Perrons Gendering the Inequality Debate

Diane Perrons Gendering the inequality debate Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Perrons, Diane (2015) Gendering the inequality debate. Gender and Development, 23 (2). pp. 207-222. ISSN 1355-2074 DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2015.1053217 © 2015 The Author This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63415/ Available in LSE Research Online: September 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Gendering the inequality debate Diane Perrons In the past 30 years, economic inequality has increased to unprecedented levels, and is generating widespread public concern amongst orthodox, as well as leftist and feminist thinkers. This article explores the gender dimensions of growing economic inequality, summarises key arguments from feminist economics which expose the inadequacy of current mainstream economic analysis on which ‘development’ is based, and argues for a ‘gender and equality’ approach to economic and social policy in both the global North and South. -

While Thomas Piketty's Bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Review of Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay, Demeter Press 2014 in Morgenbladet, Norway 4-10 July 20014 While Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. Maria Berg Reinertsen, Economics commentator in Morgenbladet, Norway The article translated: Should breastmilk be included in gross domestic product? Maria Berg Reinertsen Morgenbladet, Norway 4.July 2014 [Translated from Norwegian] We run into one of my former university professors, and I take the opportunity to expand the three-year old’s knowledge of occupations beyond firefighter and barista. "This man is doing research on money ..." "No, no," protests the professor, "not money ..." "Sorry. This man is doing research on the real economy. " The three year old is unperturbed: "That man is very tall." But the correction is important. Economists will not settle for counting money and millions, they will say something about what is happening in the real economy. But where are the limits of it? The most underestimated economic book this spring is perhaps the anthology Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics, edited by Margunn Bjørnholt and Ailsa McKay. Waring is a pioneer in feminist economics, and while Thomas Piketty’s bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century barely tests the discipline’s boundaries in its focus on the rich, Counting on Marilyn Waring challenges most limits of what economists should care about. -

Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market

Schymik, Jan: Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Munich Discussion Paper No. 2017- Department of Economics University of Munich Volkswirtschaftliche Fakultät Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Online at https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.38385 Earnings Inequality and the Global Division of Labor: Evidence from the Executive Labor Market Jan Schymik Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich May 2017 Abstract Many industrialized economies have seen a rapid rise in top income inequality and in the globalization of production since the 1980s. In this paper I propose an open economy model of executive pay to study how offshoring affects the pay level and incentives of top earners. The model introduces a simple principal-agent problem into a heterogeneous firm talent assignment model and endogenizes pay levels and the sensitivity of pay to performance in general equilibrium. Using unique data of manager-firm matches including executives from stock market listed firms across the U.S. and Europe, I quantify the model predictions empirically. Overall, I find that between 2000 and 2014 offshoring has increased executive pay levels, raised earnings inequality across executives and increased the sensitivity of pay to firm performance. JEL Classification: D2,F1,F2,J3,L2 Keywords: Offshoring; Earnings Structure, Inequality; Incentives; Executive Com- pensation Department of Economics, LMU Munich, E-mail: [email protected] I am particularly grateful to Daniel Baumgarten, David Dorn, Carsten Eckel, Florian Englmaier, Maria Guadalupe, Dalia Marin and conference audiences at the MGSE Colloquium, DFG SPP 1764 Conference IAB Nuremberg 2015 and EARIE Munich 2015 for their valuable comments. -

The Laws of Capitalism (Book Review)

BOOK REVIEW THE LAWS OF CAPITALISM CAPITAL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY. By Thomas Piketty. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2014. Pp. 685. $39.95. Reviewed by David Singh Grewal* I. CAPITALISM TODAY The past year has seen the surprising ascent of French economist Thomas Piketty to "rock star" status. 1 The reading public's appetite for his economic treatise seems motivated by a growing unease about economic inequality and an anxiety that the "Great Recession," which followed the financial crisis of 2008, defines a new economic normal. The seemingly plutocratic response to the crisis has become the focus of angry attacks by protesters on both left and right,2 but their criti cisms have had little practical effect, even while subsequent events have confirmed their fears. In 2oro, the United States Supreme Court sealed the union of corporate money and politics in Citizens United v. FEC,3 which subsequent judgments have further entrenched.4 Mean while, the response to the crisis in Europe has suggested that Brussels now operates as an arm of finance capital and that monetary union is more likely to prove the undertaker of European social democracy than its savior. 5 * Associate Professor, Yale Law School. The author thanks Ruth Abbey, Bruce Ackerman, Cliff Ando, Rick Brooks, Angus Burgin, Daniela Cammack, Paul Cammack, Stefan Eich, Owen Fiss, Bryan Garsten, Arthur Goldhammer, Jacob Hacker, Robert Hockett, Paul Kahn, Amy Kapczynski, Jeremy Kessler, Alvin Klevorick, Jonathan Macey, Daniel Markovits, Pratap Mehta, Robert Post, Jedediah Purdy, Sanjay Reddy, Roberta Romano, George Scialabba, Tim Shenk, Reva Siegel, Peter Spiegler, Adam Tooze, Richard Tuck, Patrick Weil, and John Witt for discus sions on these and related issues. -

Organization Studies of Inequality, with and Beyond Piketty

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty Citation for published version: Dunne, S, Grady, J & Weir, K 2018, 'Organization studies of inequality, with and beyond Piketty', Organization, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 165-185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508417714535 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/1350508417714535 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Organization Publisher Rights Statement: Copyright © 2018, © SAGE Publications General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Final accepted peer reviewed manuscript by Weir, K., Grady, J., and Dunne, S. accepted in Organization, 2017. Organization Studies of Inequality, with and beyond Piketty ABSTRACT Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century did much to bring discussions of economic inequality into the intellectual and popular mainstream. This paper indicates how business, management and organization studies can productively engage with Cap21st. It does this by deriving practical consequences from Piketty’s proposed division of intellectual labour in general and his account of ‘supermanagers’ in particular. -

A Review of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Journal of Economic Literature 2014, 52(2), 519–534 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.2.519 The Return of “Patrimonial Capitalism”: A Review of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century † Branko Milanovic * Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty provides a unified theory of the functioning of the capitalist economy by linking theories of economic growth and functional and personal income distributions. It argues, based on the long-run historical data series, that the forces of economic divergence (including rising income inequality) tend to dominate in capitalism. It regards the twentieth century as an exception to this rule and proposes policies that would make capitalism sustainable in the twenty-first century. ( JEL D31, D33, E25, N10, N30, P16) 1. Introduction state that we are in the presence of one of the watershed books in economic thinking. am hesitant to call Thomas Piketty’s new Piketty is mostly known as a researcher I book Capital in the Twenty-First Century of income inequality. His book Les hauts (Le capital au XXI e siècle in the French revenus en France au XXe siècle: Inégalités original) one of the best books on economics et redistributions, 1901–1998, published in written in the past several decades. Not that 2001, was the basis for several influential I do not believe it is, but I am careful because papers published in the leading American of the inflation of positive book reviews and economic journals. In the book, Piketty because contemporaries are often poor documented, using fiscal sources, the rise judges of what may ultimately prove to be (until the World War I), the fall (between influential. -

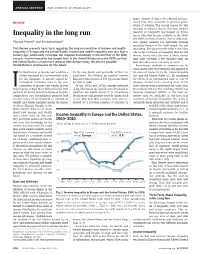

Inequality in the Long Run Survey Data That Became Available in the 1960S and 1970S in Many Countries

larger volumes of data to be collected and pro- REVIEW cessed than were accessible to previous gener- ations of scholars. The second reason for this time gap in using tax data is that most modern research on inequality has focused on micro- Inequality in the long run survey data that became available in the 1960s and 1970s in many countries. Survey data, how- 1 2 Thomas Piketty * and Emmanuel Saez ever, cannot measure top percentile incomes accurately because of the small sample size and This Review presents basic facts regarding the long-run evolution of income and wealth top coding. The top percentile plays a very large inequality in Europe and the United States. Income and wealth inequality was very high a role in the evolution of inequality that we will century ago, particularly in Europe, but dropped dramatically in the first half of the 20th discuss. Survey data also have a much shorter century. Income inequality has surged back in the United States since the 1970s so that time span—typically a few decades—than tax the United States is much more unequal than Europe today. We discuss possible data that often cover a century or more. interpretations and lessons for the future. Kuznets-type methods to construct top in- come shares were first extended and updated to he distribution of income and wealth is a for the top decile and percentile of the U.S. the cases of France (8, 9), the United Kingdom widely discussed and controversial topic. population. By dividing by national income, (10), and the United States (11). -

Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century: Global Inequality, Piketty, and the Transnational Capitalist Class

Chapter 13 Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century: Global Inequality, Piketty, and the Transnational Capitalist Class William I. Robinson Introduction Why has Thomas Piketty’s tome, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, sparked such a firestorm of debate on global inequalities in the world media, academic and policy circles? These inequalities are indeed truly savage. In 2015, the year after Piketty’s book was released in English,1 the development NGO Oxfam re- ported that the richest one percent of humanity would own more than the rest of the world in 2016.2 This is up from the one percent owning 44 percent of the world’s wealth in 2010 and 48 percent in 2014. If current trends continue, the one percent would own 54 percent by 2020. Even more shocking, the top 80 billionaires were worth $1.9 trillion in 2014, an amount equality to the bottom 50 percent of humanity and these 80 saw a 50 percent rise in their wealth in just four years. At the same time, the poorest 50 percent saw a drop in their wealth during this same four-year period from 2010 to 2014. In other words, there has been a huge transfer of wealth in a very short period of time from the poorest half of humanity to the richest 80 individuals on the planet. I do not think however, that outrage over these inequalities explains the attention that Piketty’s study has received. After all, Piketty is far from the first to draw attention to such expanding inequalities in recent years and he does not even show just how pronounced they are in the same way that Oxfam and other studies have done so. -

Unequal Countries, Was 63%

WPS7776 Policy Research Working Paper 7776 Public Disclosure Authorized Global Inequality The Implications of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century Public Disclosure Authorized Christoph Lakner Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Poverty and Inequality Team August 2016 Policy Research Working Paper 7776 Abstract In the 2000s, global inequality fell for the first time since increased in population-weighted terms, for the average the Industrial Revolution, driven by a decline in the disper- developing country the rise in inequality slowed down in sion of average incomes across countries. Between 1988 the second half of the 2000s. However, like any analysis and 2008, a period of rapidly increasing global integration, based on household surveys, these results could miss impor- income growth was largest for the global top 1 percent and tant increases in inequality if they are concentrated at the for country-deciles in Asia, often in the upper halves of the top. These data constraints remain especially serious in national distributions, while the poorer deciles in rich coun- developing countries where only very limited information tries lagged behind. Although within-country inequality on the top tail exists, especially regarding capital incomes. This paper is a product of the Poverty and Inequality Team, Development Research Group. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. Policy Research Working Papers are also posted on the Web at http://econ.worldbank.org. The author may be contacted at [email protected]. -

Is There a Global Super‐Bourgeoisie?

Received: 11 January 2021 Revised: 24 March 2021 Accepted: 24 March 2021 DOI: 10.1111/soc4.12883 ARTICLE - - Is there a global super‐bourgeoisie? Bruno Cousin1 | Sébastien Chauvin2 1Centre for European Studies and Comparative Politics (CEE), Sciences Po, Abstract Paris, France In recent decades, accelerating processes of globalization 2Institute of Social Sciences (ISS), University and an increase in economic inequality in most of the of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland world's countries have raised the question of the emer- Correspondence gence of a new bourgeoisie integrated at the global level, Bruno Cousin, Sciences Po‐CEE, 27 rue Saint‐ Guillaume, 75337 Paris Cedex 07, France. sometimes described as a global super‐bourgeoisie. This Email: [email protected] group would be distinguished by its unequaled level of wealth and global interconnectedness, its transnational ubiquity and concentration in the planet's major global cities, its specific culture, consumption habits, sites of so- ciability and shared references, and even by class con- sciousness and capacity to act collectively. This article successively discusses how the social sciences have exam- ined these various dimensions of the question and begun to provide systematic empirical answers. KEYWORDS bourgeoisie, class, economic elites, global elite, inequality, super‐ rich, transnationalism 1 | INTRODUCTION In the past decades, accelerating processes of globalization and an increase in economic inequality in most of the world's countries have raised the question of the possible emergence of a new bourgeoisie now integrated at the global level (Dahrendorf, 2000) or, as some have called it, of a global “super‐bourgeoisie” (Cousin & Chauvin, 2015; Duclos 2002; Wagner 2017). -

A Review Essay of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century

Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, Volume 7, Issue 2, Autumn 2014, pp. 73-115. http://ejpe.org/pdf/7-2-art-4.pdf Measured, unmeasured, mismeasured, and unjustified pessimism: a review essay of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the twenty-first century DEIRDRE NANSEN MCCLOSKEY University of Illinois at Chicago Keywords: Piketty, capitalism, inequality JEL Classification: B40, B50, I32, N30, P10 Thomas Piketty has written a big book, 577 pages of text, 76 pages of notes, 115 charts, tables, and graphs, that has excited the left, worldwide. “Just as we said!” the leftists cry. “The problem is Capitalism and its inevitable tendency to inequality!” First published in French in 2013, an English edition was issued by Harvard University Press in 2014 to wide acclaim by columnists such as Paul Krugman, and a top position on the New York Times best-seller list. A German edition came out in late 2014, and Piketty—who must be exhausted by all this—worked overtime expositing his views to large German audiences. He plays poorly on TV, because he is lacking in humor, but he soldiers on, and the book sales pile up. It has been a long time (how does “never” work for you?) since a technical treatise on economics has had such a market. An economist can only applaud. And an economic historian can only wax ecstatic. Piketty’s great splash will undoubtedly bring many young economically interested scholars to devote their lives to the study of the past. That is good, because economic history is one of the few scientifically quantitative branches of economics. -

The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality in America: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 34, Number 4—Fall 2020—Pages 3–26 The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality in America: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman or the measurement of income and wealth inequality, there is no equivalent to Gross Domestic Product statistics—that is, no government-run standardized, F documented, continually updated, and broadly recognized methodology similar to the national accounts which are the basis for GDP. Starting in the mid- 2010s, we have worked along with our colleagues from the World Inequality Lab to address this shortcoming by developing “distributional national accounts”— statistics that provide consistent estimates of inequality capturing 100 percent of the amount of national income and household wealth recorded in the official national accounts. This effort is motivated by the large and growing gap between the income recorded in the datasets traditionally used to study inequality—household surveys, income tax returns—and the amount of national income recorded in the national accounts. The fraction of national income that is reported in individual income tax data has declined from 70 percent in the late 1970s to about 60 percent in 2018. The gap is larger in survey data, such as the Current Population Survey, which do not capture top incomes well. This gap makes it hard to address questions such as: What fraction of national income is earned by the bottom 50 percent, the middle 40 percent, and the top 10 percent of the distribution? Who has benefited from economic growth since the 1980s? How does the growth experience of the ■ Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman are Professors of Economics, both at the University of California, Berkeley, California.