Cyclopean Cannibalism Wes Mcgee University of Michigan / Matter Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stone Source Glossary of Terms.Indd

GLOSSARY OF TERMS This glossary provides you with commonly used terms for each of our material UPDATED ON: 9.13.2012 categories. The guide is divided into 5 sections: • Natural Stone • Porcelain tile + Ceramic tile • Glass Tile • Engineered Stone • Wood New York Boston Chicago Los Angeles New Jersey Washington DC Natural Stone Porcelain Tile Glass Tile Engineered Stone Reclaimed Wood 1 of 21 - stone source Glossary of terms GLOSSARY OF TERMS: Natural stone These are the terms most commonly used in relation to Natural Stone: Bleed Staining caused by corrosive metals, oil-based putties, mastics, caulking, or Abrasion resistance sealing compounds. The ability of a material to resist surface wear. Book Matched Absorption Layout wherein slabs are cut to create a mirror image of each other. The relative porosity of the material. Materials with low absorption will be less prone to staining. Materials with high-absorption may not be suitable for all applications, specifically kitchen countertops that come into regular contact with oils or pigmented acidic liquids such as wine or balsamic vinegar. Acid etching Materials that contain calcium or magnesium carbonate (marble, travertine, limestone and onyx) will react to acidic foods such as lemons or tomatoes. This reaction will result in a change in surface sheen, otherwise referred to as “acid etching”. Lighter stones and honed surfaces will typically diminish the appearance of acid etching. Antiqued finish Brushed finish A finish with a worn aged appearance, achieved by mechanically rubber- A smooth finish achieved by brushing a stone with a coarse rotary-type wire brushing the tile. brush. Buttering / Back buttering bullnose edge The process of slathering the back of a stone tile with thinset material to ensure (see edge profiles on page 8) proper mortar coverage. -

Brick Masonry Brick

Brick Masonry Brick • Brick is a basic building unit which is in the form of rectangular block in which length to breadth ratio is 2 but height can be different. • Normal size (nominal size) • 9''×4½" ×3" • Architectural size (Working size) • 81⅟16" x 4⁵⁄₁₆" x 21⅟16" • Brick Masonary The art of laying bricks in mortor in a proper systematic manner gives homogeneous mass which can withstand forces without disintigration, called brick masonary. Terminology: The surfaces of a brick have names: Top and bottom surfaces are beds. Ends are headers and header faces. Sides are stretchers or stretcher faces. Bricks are the subject of British Standard BS 3921. Brick Sizes A standard metric brick has coordinating dimensions of 225 x 112.5 x 75 mm (9''×4½" ×3“) called nominal size and working dimensions (actual dimensions) of 215 x 102.5 x 65 mm (8.5“ * 4 *2.5) called architectural size Brick Sizes Brick Sizes The coordinating dimensions are a measure of the physical space taken up by a brick together with the mortar required on one bed , one header face and one stretcher face. The working dimensions are the sizes to which manufacturers will try to make the bricks. Methods of manufacture for many units and components are such that the final piece is not quite the size expected but it can fall within the defined limits. This can be due to the things like shrinkage, distortion when drying out, firing etc. The difference between the working and coordinating dimensions of a brick is 10mm (0.5“)and this difference is taken up with the layer of mortar into which the bricks are pressed when laying. -

The Monumental Architecture of Iklaina

The Monumental Architecture of Iklaina Michael B. Cosmopoulos1 Abstract: The excavations of the Athens Archaeological Society at Iklaina have brought to light a major LH settle- ment that is identified with *a-pu2, one of the district capitals of the Mycenaean state of Pylos. One of the most striking features of the site is its monumental architecture, which includes at least two large buildings, two paved roads, a paved piazza, and massive built stone drains. The presence of this kind of monumentality outside the traditionally defined ‘palaces’, combined with other markers of advanced socio-political complexity, opens up a number of questions regard- ing the processes of the unification of the Mycenaean state of Pylos. In the present paper I review the relevant archi- tectural and stratigraphic evidence and assess its possible implications for this issue. It is concluded that the emergence of monumental architecture at Iklaina could have been initiated either by the Palace of Nestor following a peaceful annexation of Iklaina in the early Mycenaean period, or by the local Iklaina rulers following a period of continuous growth before a forced annexation in LH IIIB. Keywords: Monumentality, state formation, Mycenaean, Pylos, Iklaina Introduction The excavations at Iklaina are conducted under the auspices of the Archaeological Society at Athens.2 Over the course of nine field seasons we have unearthed a significant part of a LH settle- ment, which can be identified with *a-pu2, one of the district capitals of the Mycenaean state of Pylos.3 The site includes three general areas: residential, industrial, and administrative (marked as R, I, and A in Fig. -

Wall Tiling Installation Guide

Wall Tiling Installation Guide February 2017 1 Important Notes 3 Internal Wall Substrates 4-5 Planning 6 General Information 7-8 Installing: Glass tiles. 9-11 Glass tiles with Painted backs & Protective Layers. Installing: Installing Glass Mosaics. 12-15 Installing Glass & Slate Mosaics. Installing Crackle Glaze tiles. 16-17 Installing Glazed Ceramic & Porcelain tiles. 18-19 Installing Mother of Pearl. 20-21 Installing Floor tiles on a wall. 21 Product Notes. 22 Glossary. 22 Substrate Preparation Guide. 23 Tile Essentials Product Selector – Glazed Wall Tiles. 24-26 Tile Essentials Product Selector – Stone / Slate / Mother of Pearl. 27-28 Tile Essential Product Selector – Glass Wall Tiles. 29-30 Tile Essential Product Selector – Floor Tiles. 30 Sealants and Finishes. 31 2 Important Notes The purpose of this booklet is to outline the basic principles of installing Fired Earth wall tiles. This is intended as a guide, we would always recommend you refer to British Standard BS 5385 Wall and Floor Tiling for more detailed technical information. Prior to installation please ensure the tiles purchased are suitable for the application and thoroughly inspected. Ensure your tiler is aware of the expected finish of the tiles and there are sufficient tiles for the area. The tiles must be well shuffled by drawing tiles from all the boxes. Dry lay an area in suitable light as a final check before installation. For further information or if any doubt exists, please telephone our Technical Department for advice prior to commencing any tiling. Fired Earth have tested our range of adhesives, grout and sealants to ensure compatibility with all of our tiles (see our Product Selector on pages 25 to 31). -

How to Build a Dry Stone Wall an Instructional Guide for Beginners

Do- It-Yourself: How to Build a Dry Stone Wall An instructional guide for beginners © Copyright Stephen Burton and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License. By: Stephen T. Kane Table of Contents: INTRODUCTION………………………………………………….3 TOOLS, EQUIPMENT, AND SUPPLIES………………………4 GROUNDWORK…………….…………………………………….7 FOUNDATION…………………………………………………….8 COURSING.…………………………………………………………9 COPING.……………………………………………………………10 GLOSSARY………………………………………………………..11 Introduction: Whether for pure aesthetics or practical functionality, dry stone walls employ the craft of carefully stacking and interlocking stones without the use of mortar to form earthen boundaries, residential foundations, agricultural terraces, and rudimentary fences. If properly constructed, these creations will stand unabated for countless years, requiring only minimal maintenance and repairs. The ability to harness the land and shape it in a way that meets one’s needs through stone walling allows endless possibility and enjoyment after fundamental steps and basic techniques are learned. How to Build a Dry Stone Wall provides a comprehensive reference for beginners looking to start and finish a wall project the correct way. A list of essential resources and tools, a step-by-step guide, and illustrations depicting proper construction will allow readers to approach projects with a confidence and a precision that facilitates the creation of beautiful stonework. If any terminology poses an issue, simply reference the glossary provided in the back of the booklet. NOTE: Depending on property laws and building codes, many areas do not permit stone walls. Check with respective sources to determine if all residential rules and regulations will abide stonework. Also, before building anything on a property line, always consult your neighbor(s) and get their written consent. -

![SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices Including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5611/sp-20-1991-handbook-on-masonry-design-and-construction-ced-13-building-construction-practices-including-painting-varnishing-and-allied-finishing-875611.webp)

SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices Including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” HANDBOOK ON MASONRY DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION (First Revision) BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 SP 20(S&T) : 1991 FIRST PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 1981 FIRST REVISION MARCH 1991 0 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS 1991 UDC 693 ISBN 81-7061-029-X PRICE Rs 200.00 PRINTED IN INDlA AT KAPOOR ART PRESS, A3813 MAYAPURI, NEW DELHI AND PUBLISHED BY BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS, NEW DELHI 110002 . -

Masonry Constructions As Built Archives: an Innovative Analytical Approach to Reconstructing the Evolution of Imperial Opus Testaceum Brickwork in Rome

Masonry Constructions as Built Archives: An Innovative Analytical Approach to Reconstructing the Evolution of Imperial Opus Testaceum Brickwork in Rome Gerold Eßer Vienna University of Technology, Austria The Colosseum, Trajan’s Market, the Baths of buil dings are to be regarded as the outcome of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius: the monu- rational decisions made on the basis of economy, mental ruins of the imperial representational build- durability and functionality. Particularly in the ings mark the crystallisation points in a profound, area of important imperial public buildings, where centuries- long recasting of the appearance of the the pressure to be successful was exceptionally city of Rome (Fig. 1). The cores consist of practi- high, the conditions imposed by the market were cally indestructible opus caementitium, faced with certainly strictly observed. Large imperial buil- hard, quasi- industrially produced fired bricks. This ding projects in which often many thousands of construction method, later called opus testaceum, workers had to be organised and directed required was uniquely suited to surviving the passage of the definition and implementation of standards time. For us today, this means that we have at our applicable right across the site. To ensure the suc- disposal an extraordinary wealth of evidence for the cess of a major project these standards had to be building construction methods used in those times. laid down in series of technical regulations. The Given that even the building sites of classi- doctoral thesis on which the present paper is based cal antiquity were subject to market forces, the examined the extent to which the organisation of large building sites influenced masonry construc- tions and whether, using the characteristics of the masonry that will be defined below, this influence can be read as a regulative on the erection of the structures. -

Brickwork and Modern Methods of Construction

January 2020 BRICKWORK AND MODERN METHODS OF CONSTRUCTION Brick Development Association www.brick.org.uk BRICKWORK & MMC 2 Contents Page INTRODUCTION 03 MMC DEFINITIONS 04 HISTORY OF BRICKWORK MMC 05 SLIP PANEL SYSTEMS - INDIVIDUAL SLIPS 06 - PANEL SYSTEMS 07 - RAIL AND TILE 08 PRECAST CONCRETE 09 PRE FABRICATED COMPONENTS 10 ROBOTICS 11 DESIGN & SPECIFICATION 12 REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING 15 SEVERELYBRICKWORK EXPOSED & MMC BRICKWORK 3 INTRODUCTION In construction there is a continuous desire to build projects to a higher quality, on a shorter timescale and at a reduced cost. The government's Construction Sector Deal challenges the industry to reduce construction cost by 1/3 and construction time by 1/2, whilst improving quality. One of the key drivers identified to achieve these targets is the development and expansion of Modern Methods of Construction. Brick manufacturers have been at the forefront of developing MMC systems for several years. Clay brick has undergone a dramatic transformation during the 20th century. From solid wall construction to the modern cavity wall, with improved levels of insulation and reduced water penetration. CAUTION REQUIRED The sector needs to be mindful that during the push for quicker and cheaper we don't compromise the quality of what is built, as has happened with previous attempts to develop MMC. One of the principal benefits of hand laid clay brick is that it has a very long history of quality performance with a large and proven supply chain. Assessing when it is appropriate to use a MMC system, to gain maximum Traditional solid wall construction benefits, has historically been a complex issue. -

DRY STONE WALLS Fig

INFORM DRY STONE WALLS Fig. 1: Two regional variations showing how local geology influences walling style. Composition of dry stone walls DRY STONE WALLS Dry stone construction is an ancient This INFORM guide aims to broaden building technique, where the walls are the awareness of the importance constructed from carefully positioned and complexity of dry stone walling interlocking stones placed on top of in Scotland, and it outlines common each other without the use of mortar. causes of deterioration and the Pressure from the stones at the top maintenance required to prolong the and the way the stones are interlocked life of such walls. ensures the self-supporting stability of the wall. However, there is more to the Dry stone walls, or drystane dykes as construction of a dry-stone wall than known in Scotland, are an integral part randomly setting stone upon stone; of the built heritage and landscape the skill required to properly construct of Scotland. They perform several a wall without mortar that will last for functions, such as to delineate several hundred years is considerable. boundaries, to corral livestock and to provide shelter for wildlife. Despite The construction of the wall depends the many thousands of miles of dry on the quantity and types of stone stone walling which can be seen available. Although today it is possible forming field boundaries and related to source quarried stone, walls would structures, it is a much neglected have originally been constructed with and misunderstood part of the built stones found on local ground. There heritage. Both their construction are regional variations in the type of and repair are complex tasks that stone used for dry stone walls, as the should not be undertaken lightly; It local geology varies from one place is recommended that any large-scale to another, dictating the shape and repair is performed by a competent or size of available stone, as well as the accredited dyker. -

Seismic Performance of Rock Block Structures with Observations from the October 2006 Hawaii Earthquake

4th International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering June 25-28, 2007 SEISMIC PERFORMANCE OF ROCK BLOCK STRUCTURES WITH OBSERVATIONS FROM THE OCTOBER 2006 HAWAII EARTHQUAKE Edmund MEDLEY 1, Dimitrios ZEKKOS 2 ABSTRACT Unreinforced masonry construction using blocks of rock is one of the oldest forms of building, in which blocks are stacked, sometimes being mortared with various cements. Ancient civilizations used locally available rocks and cements to construct rock block columns, walls and edifices for residences, temples, fortifications and infrastructure. Monuments still exist as testaments to the high quality construction by historic cultures, despite the seismic and other potentially damaging geomechanical disturbances that threaten them. Conceptual failure modes under seismic conditions of rock block structures, observed in the field or the laboratory, are presented. A brief review is presented of the damage suffered by the culturally vital Hawaiian Pu’ukoholā and Mailekini Heiaus, rock block temples damaged by the Mw 6.7 and 6.0 earthquakes that shook the island of Hawaii on October 15, 2006. Keywords: rock block structures, Hawaii earthquakes, earthquake observations, geomechanical failures INTRODUCTION Construction of unreinforced masonry is common in various earthquake-prone regions, particularly in developing countries, and rural areas of developed countries. This vulnerable type of construction is susceptible to often devastating damage, as evident from the effects of the 2001 Bhuj, India earthquake (Murty et al. 2002), where 1,200,000 masonry buildings built primarily based on local traditional construction practices, either collapsed or were severely damaged. Buildings constructed with adobe and unreinforced masonry suffered devastating damage in the Bam, Iran 2003 earthquake (Nadim et al. -

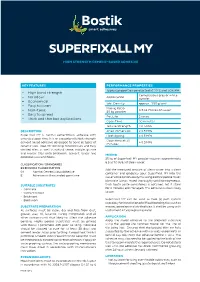

Superfixall My

SUPERFIXALL MY HIGH STRENGTH CEMENT-BASED ADHESIVE KEY Features Performance Properties Typical properties conducted at 22oC and 50% RH – High bond strength Cementitious grey or white Appearance – No odour powder – Economical Wet Density approx. 1.55 g/cm3 – Easy to clean Mixing Ratio 6.5 to 7 litres of water – Non-toxic 25 kg powder – Easy to spread Pot Life 2 hours – Thick and thin bed applications Open Time 30 minutes Tensile Strength ≥ 0.5 MPa DESCRIPTION After Immersion ≥ 0.5 MPa Superfixall MY is normal cementitious adhesive with Heat Ageing ≥ 0.5 MPa extended open time. It is an exceptionally high strength Open time at 30 cement based adhesive developed to bond all types of ≥ 0.5 MPa minutes ceramic tiles. Ideal for bonding monocottura and fully vitrified tiles, as well as natural stone, marble, granite and mosaic tiles onto brickwork, cement render and MIXING concrete walls and floors. 25 kg of Superfixall MY powder requires approximately 6.5 to 7.0 litres of clean water. CLASSIFICATION / STANDARDS BS EN12004 CLASSIFICATION Add the measured amount of clean water into a clean C1 Normal Cementitious Adhesive container and gradually pour Superfixall MY into the E Adhesive with extended open time water while continuously mix using electric paddle mixer. Eliminate lumps. Mixed thoroughly until homogeneous, SUITABLE SUBSTRATES thick tooth paste consistency is obtained. Let it stand • Concrete for 2 minutes and mix again. The adhesive is now ready • Cement render to use. • Brickwork • Blockwork Superfixall MY can be used as two (2) part system especially for installation of difficult bonding tiles such as SUBstrate preparation mosaic, porcelain and vitrified tiles. -

MASON (Building Constructor)

CURRICULUM FOR THE TRADE OF MASON (Building Constructor) UNDER APPRENTICESHIP TRAINING SCHEME (ATS) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SKILL DEVELOPMENT & ENTREPRENURESHIP DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF TRAINING 1 CONTENTS Sl. No. Topics Page No. 1. Acknowledgement 03 2. Background 04 – 05 2.1 Apprenticeship Training under Apprentice Act 1961 2.2 Changes in Industrial Scenario 2.3 Reformation 3. Rationale 06 4. Job roles: reference NCO 07 5. General Information 08 6. Course structure 09 – 10 7. Syllabus 11 – 27 7.1 Basic Training 7.1.1 Detail syllabus of Core Skill A. Block-I (Engg. drawing & W/ Cal. & Sc.) B. Block-II (Engg. drawing & W/ Cal. & Sc.) 7.1.2 Detail syllabus of Professional Skill & Professional Knowledge A. Block – I B. Block – II 7.1.3 Employability Skill 7.1.3.1 Syllabus of Employability skill A. Block – I B. Block – II 7.2 Practical Training (On-Job Training) 7.2.1 Broad Skill Component to be covered during on-job training. A. Block – I B. Block – II Assessment Standard 28 – 30 8.1 Assessment Guideline 8. 8.2 Final assessment-All India trade Test (Summative assessment) 9. Further Learning Pathways 31 2 10. Annexure-I – Tools & Equipment for Basic Training 32 – 35 11. Annexure-II – Infrastructure for On-Job Training 36 12. Annexure-III - Guidelines for Instructors & Paper setter 37 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The DGT sincerely express appreciation for the contribution of the Industry, State Directorate, Trade Experts and all others who contributed in revising the curriculum. Special acknowledgement to the following industries/organizations who have contributed valuable inputs in revising the curricula through their expert members: 1.