Appendix A: International Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

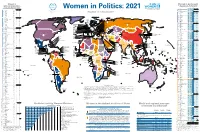

Women in Ministerial Positions, Reflecting Appointments up to 1 January 2021

Women in Women in parliament The countries are ranked and colour-coded according to the percentage of women in unicameral parliaments or the lower house of parliament, ministerial positions reflecting elections/appointments up to 1 January 2021. The countries are ranked according to the percentage of women in ministerial positions, reflecting appointments up to 1 January 2021. Rank Country Lower or single house Upper house or Senate % Women Women/Seats % Women Women/Seats Rank Country % Women Women Total ministers ‡ Women in Politics: 2021 50 to 65% 50 to 59.9% 1 Rwanda 61.3 49 / 80 38.5 10 / 26 1 Nicaragua 58.8 10 17 2 Cuba 53.4 313 / 586 — — / — 2 Austria 57.1 8 14 3 United Arab Emirates 50.0 20 / 40 — — / — ” Belgium 57.1 8 14 40 to 49.9% ” Sweden 57.1 12 21 4 Nicaragua 48.4 44 / 91 — — / — 5 Albania 56.3 9 16 Situation on 1 January 2021 5 New Zealand 48.3 58 / 120 — — / — 6 Rwanda 54.8 17 31 6 Mexico 48.2 241 / 500 49.2 63 / 128 7 Costa Rica 52.0 13 25 7 Sweden 47.0 164 / 349 — — / — 8 Canada 51.4 18 35 8 Grenada 46.7 7 / 15 15.4 2 / 13 9 Andorra 50.0 6 12 9 Andorra 46.4 13 / 28 — — / — ” Finland 50.0 9 18 10 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 46.2 60 / 130 55.6 20 / 36 ” France 50.0 9 18 11 Finland 46.0 92 / 200 — — / — ” Guinea-Bissau* 50.0 8 16 12 South Africa 45.8 182 / 397 41.5 22 / 53 ” Spain 50.0 11 22 13 Costa Rica 45.6 26 / 57 — — / — 40 to 49.9% 14 Norway 44.4 75 / 169 — — / — 14 South Africa 48.3 14 29 15 Namibia 44.2 46 / 104 14.3 6 / 42 15 Netherlands 47.1 8 17 Greenland Latvia 16 Spain 44.0 154 / 350 40.8 108 / 265 16 -

Report of the Regional Director

The W ork of WHO in the South-East Asia Region 2018 The Work of WHO in the South-East Asia Region Report of the Regional Director Report of the Regional Director This report describes the work of the World Health Organization in the South-East 1 January–31 December Asia Region during the period 1 January–31 December 2018. It highlights the achievements in public health and WHO's contribution to achieving the 1 January–31 December 2018 Organization's strategic objectives through collaborative activities. This report will be useful for all those interested in health development in the Region. ISBN 978 92 9022 717 5 www.searo.who.int https://twitter.com/WHOSEARO https://www.facebook.com/WHOSEARO 9 789290 227175 SEA/RC72/2 The work of WHO in the South-East Asia Region Report of the Regional Director 1 January–31 December 2018 The Work of WHO in the South-East Asia Region, Report of the Regional Director, 1 January–31 December 2018 ISBN: 978 92 9022 717 5 © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. -

Robert Asaadi, Department of Political Science, Portland State

“Institutional Power Sharing in the Islamic Republic of Iran” Robert Asaadi, Department of Political Science, Portland State University 2021 Western Political Science Association Panel: Governance, Identities, Religion and Politics *Please do not cite or circulate without the permission of the author Keywords: Iran; Middle East; Comparative Politics; Political Institutions 1 The Constitution of the Islamic Republic establishes a semipresidential system, where executive power is divided between the supreme leader and the president. Prior to the 1989 constitutional amendments, the system also included a third executive—a prime minister; however, this position was abolished by the amendments, and the office of the presidency was strengthened in its wake. According to the language of the Constitution, the supreme leader’s position (referred to in the text of the Constitution as the “Leader”) is considered separate from the executive, legislative, and judicial branches (which the Constitution refers to as the “three Powers”). Although the supreme leader takes on a number of functions that are commonly associated with these branches of government elsewhere in the world, the position of the “Leader or Council of Leadership” is conceptually distinct from the “three Powers,” and, in fact, is tasked with resolving disputes and coordinating relations between the three branches.i Along with this dispute resolution power, article 110 outlines the ten additional express powers of the Leader: determining the general policies of the political system -

A Changing of the Guards Or a Change of Systems?

BTI 2020 A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa Nic Cheeseman BTI 2020 | A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa By Nic Cheeseman Overview of transition processes in Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe This regional report was produced in October 2019. It analyzes the results of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2020 in the review period from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2019. Author Nic Cheeseman Professor of Democracy and International Development University of Birmingham Responsible Robert Schwarz Senior Project Manager Program Shaping Sustainable Economies Bertelsmann Stiftung Phone 05241 81-81402 [email protected] www.bti-project.org | www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en Please quote as follows: Nic Cheeseman, A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI Regional Report Sub-Saharan Africa, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.11586/2020048 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Cover: © Freepick.com / https://www.freepik.com/free-vector/close-up-of-magnifying-glass-on- map_2518218.htm A Changing of the Guards or A Change of Systems? — BTI 2020 Report Sub-Saharan Africa | Page 3 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................... -

Lesotho's Technology Needs Assessment

Lesotho Meteorological Services Ministry of Natural Resources ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE TECHNOLOGY NEEDS IN LESOTHO Energy and Land Use Change and Forestry TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE i LIST OF ACRONYMS ii LIST OF PEOPLE INTERVIEWED iii I. BACKGROUND 1 Socio-economic conditions 1 National development objectives 1 Poverty alleviation 1 Employment creation 1 Social integration 2 Conservation of the land base 2 The future path of development 4 The role of science and technology in development 4 Agro-climatic conditions 5 Climate change scenarios 5 The draft technology development policy 6 International and regional perspectives 7 II. NATIONAL EXPERIENCES 10 Introduction 10 Agricultural research 10 Appropriate technology research 11 Labour-intensive construction 12 Rural water supplies 13 The rural sanitation programme 13 Low-cost housing development 14 Other initiatives 14 Technology registration 15 Technology transfer mechanisms 15 Shows, fairs and exhibitions 15 Extension services 15 Radio and other services 16 III. TECHNOLOGY, EDUCATION AND TRAINING 17 Introduction 17 Current education and training policies 17 Curriculum development 18 School programmes 20 Technical and vocational training 21 University and other tertiary training 22 Other related initiatives 23 Industrial training and support 23 Small contractor training 24 Skills training 24 Trades testing 24 IV. TECHNOLOGY NEEDS IN THE ENERGY SECTOR 26 Introduction 26 Challenging issues 28 Sector Institutions 29 Overall policies and strategies 30 Options for Technology Transfer in the Sector 32 Renewable energy technologies 32 Hydro-power development 33 Solar photovoltaic technologies 34 Solar thermal technologies 34 Wind energy 35 Biogas technology 35 Energy Conservation 36 Energy efficiency/conservation in the residential sector 36 Energy efficiency/conservation in commerce and industry 36 Energy efficiency/conservation in the transport sector 37 Energy efficiency/conservation in government buildings 37 Passive solar design in buildings 37 Energy efficient cooking devices/stoves 37 Energy auditing 38 V. -

![[ 1986 ] Part 1 Sec 3 Chapter 4 Other Colonial Territories](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1967/1986-part-1-sec-3-chapter-4-other-colonial-territories-121967.webp)

[ 1986 ] Part 1 Sec 3 Chapter 4 Other Colonial Territories

Other colonial Territories 961 Chapter IV Other colonial Territories With the dispute between Argentina and the United Argentina charged that United Kingdom aircraft Kingdom over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) re- had overflown and harassed Argentine fishing maining unresolved, the General Assembly in vessels—on 11 and 15 August,(1) 1 October(2) and November 1986 again requested both parties to initiate 24 November(3)—outside the so-called protection negotiations and the Secretary-General to continue zone which the United Kingdom had unilaterally his good offices mission to assist them (resolution 41/40). set up at 150 nautical miles around the Malvinas. In addition to that question, the Special Com- The United Kingdom denied those charges—in let- mittee on the Situation with regard to the Implemen- ters dated 4 September,(4) 10 October(5) and 15 tation of the Declaration on the Granting of Inde- December(6)—saying that the vessels were found pendence to Colonial Countries and Peoples within the zone and that its aircraft approached the (Committee on colonial countries) continued to ex- ships to confirm their identity without harassing amine the situations in Western Sahara and East them in any way. Timor and decided to review them again in 1987. Conservation measures in the South Atlantic In October, the Assembly reaffirmed that Western fishing grounds were the subject of a series of let- Sahara was a decolonization matter and again re- ters. On 22 September,(7) the United Kingdom ex- quested Morocco and the Frente Popular para la pressed its concern over a report that Argentina had Liberación de Saguia el-Hamra y de Río de Oro concluded with the USSR a bilateral fisheries agree- to negotiate a cease-fire and a referendum for self- ment purportedly applicable to the waters around determination of the people of the Territory (41/16). -

STATES of JERSEY R

STATES OF JERSEY r DRAFT STATES OF JERSEY (AMENDMENT No. 5) LAW 200- (P.183/2007): SECOND AMENDMENTS (P.183/2007 AMD.(2)) – COMMENTS Presented to the States on 11th January 2007 by the Privileges and Procedures Committee STATES GREFFE COMMENTS Deputy de Faye is proposing 3 amendments to PPC’s proposals – (1) to increase the mandate of Senators to 8 years; (2) to restrict the senatorial position to candidates who have been States members for at least 12 months; and (3) to allow the Chief Minister to propose a ministerial ‘reshuffle’ after any by-election. The Privileges and Procedures Committee does not support these amendments even though they do not fundamentally undermine the Committee’s proposal to move to a 4 year cycle for the Assembly. In relation to the first proposed amendment PPC believes that an 8 year term for Senators would be far too long. The Committee considers that an effective parliamentary democracy requires the renewal of the mandate of elected members at regular intervals. Issues of concern and circumstances can change quickly in any society and are unlikely to remain constant over an 8 year period. Research undertaken by PPC (see Appendix) shows that most Commonwealth parliamentarians are required to face the electorate at intervals of between 3 to 5 years with only a few having terms of 6 years. A senatorial term in Jersey of 8 years would therefore appear to be almost unique in the Commonwealth. It is of note that the French Presidential term of 7 years was reduced to 5 years in 2002 and the 9 year term of French Senators reduced to 6 years in 2003. -

Pakistan) Kumari Navaratne (Sri Lanka) G

Public Disclosure Authorized BETTER REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH FOR POOR WOMEN IN SOUTH ASIA Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Report of the South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Analytical and Advisory Activity MAY 2007 Authors Meera Chatterjee Ruth Levine Shreelata Rao-Seshadri Nirmala Murthy Team Meera Chattejee (Team Leader) Ruth Levine (Adviser) Bina Valaydon (Bangladesh) Farial Mahmud (Bangladesh) Tirtha Rana (Nepal) Shahnaz Kazi (Pakistan) Kumari Navaratne (Sri Lanka) G. Srihari (Program Assistant) Research Analysts Pranita Achyut P.N. Rajna Ruhi Saith Anabela Abreu: Sector Manager, SASHD Julian Schweitzer: Sector Director, SASHD Praful Patel: Vice President, South Asia Region Consultants Bangladesh International Center for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh Data International, Bangladesh India Indicus Analytics, New Delhi Foundation for Research in Health Systems, Bangalore Nepal New Era, Kathmandu Maureen Dar Iang, Kathmandu Pakistan Population Council, Pakistan Sri Lanka Medistat, Colombo Institute for Participation in Development, Colombo Institute of Policy Studies, Sri Lanka This study and report were financed by a grant from the Bank-Netherlands Partnership Program (BNPP) BETTER REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH FOR POOR WOMEN IN SOUTH ASIA CONTENTS ACRONYMSAND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. V Chapter 1. Reproductive Health in South Asia: Poor and Unequal... 1 WHY FOCUS ON REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH INSOUTH ASIA? ........................ 2 HOW THIS -

Turnout in Developed and Developing Countries: Are the Two Turnout Functions Different Or

Turnout in developed and developing countries: Are the two turnout functions different or the same? Abstract In the literature on political participation, there is no baseline model of electoral turnout. Rather, various studies (e.g. Blais 2006, Franklin 1999, 2004, Geys 2006, Remmer 2009), which employ different sample sizes, time periods, cases, and operationalizations of relevant independent variables, produce contradictory results. To shed light on these diverse findings, I evaluate whether different levels of development trigger different turnout functions. My results indicate that highly developed countries have higher levels of citizen participation in elections, and even more importantly, they illustrate that the turnout function in high income and low/medium income countries is quite dissimilar. The GDP per capita, compulsory voting and decisive elections have a different impact in the two universes of cases. This implies that there are two distinct turnout functions between developed and developing nations. Keywords: Turnout, developed countries, developing countries 1 Introduction Elections are instruments of democracy. Probably more so than any other feature (e.g. political rights and human rights), competitive, free and fair elections demonstrate a nation-state’s commitment to democracy (Huntington 1984; Schumpeter 1976). Through elections, citizens can choose and oust policymakers and impact political outcomes. High voter participation gives legitimacy to those in power; it increases the authority of the democratic system as a whole and leads to less violence and instability (Franklin 2004; Powell 1986). In contrast, the presence of large amounts of citizens, who do not fulfill their civic duty and do not cast ballots, is a sign of apathy toward the democratic system (Dettrey and Schwindt-Bayer 2009). -

Guardian Politics in Iran: a Comparative Inquiry Into the Dynamics of Regime Survival

GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Payam Mohseni, M.A. Washington, DC June 22, 2012 Copyright 2012 by Payam Mohseni All Rights Reserved ii GUARDIAN POLITICS IN IRAN: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY INTO THE DYNAMICS OF REGIME SURVIVAL Payam Mohseni, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Daniel Brumberg, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The Iranian regime has repeatedly demonstrated a singular institutional resiliency that has been absent in other countries where “colored revolutions” have succeeded in overturning incumbents, such as Ukraine, Georgia, Serbia, Kyrgyzstan and Moldova, or where popular uprisings like the current Arab Spring have brought down despots or upended authoritarian political landscapes, including Egypt, Tunisia, Yemen, Libya and even Syria. Moreover, it has accomplished this feat without a ruling political party, considered by most scholars to be the key to stable authoritarianism. Why has the Iranian political system proven so durable? Moreover, can the explanation for such durability advance a more deductive science of authoritarian rule? My dissertation places Iran within the context of guardian regimes—or hybrid regimes with ideological military, clerical or monarchical institutions steeped in the politics of the state, such as Turkey and Thailand—to explain the durability of unstable polities that should be theoretically prone to collapse. “Hybrid” regimes that combine competitive elections with nondemocratic forms of rule have proven to be highly volatile and their average longevity is significantly shorter than that of other regime types. -

The Year in Elections, 2013: the World's Flawed and Failed Contests

The Year in Elections, 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Norris, Pippa, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martinez i Coma. 2014. The Year in Elections 2013: The World's Flawed and Failed Contests. The Electoral Integrity Project. Published Version http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/ Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11744445 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 THE WORLD’S FLAWED AND FAILED CONTESTS Pippa Norris, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martínez i Coma February 2014 THE YEAR IN ELECTIONS, 2013 WWW. ELECTORALINTEGRITYPROJECT.COM The Electoral Integrity Project Department of Government and International Relations Merewether Building, HO4 University of Sydney, NSW 2006 Phone: +61(2) 9351 6041 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com Copyright © Pippa Norris, Ferran Martínez i Coma, and Richard W. Frank 2014. All rights reserved. Photo credits Cover photo: ‘Ballot for national election.’ by Daniel Littlewood, http://www.flickr.com/photos/daniellittlewood/413339945. Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 6 and 18: ‘Ballot sections are separated for counting.’ by Brittany Danisch, http://www.flickr.com/photos/bdanisch/6084970163/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. Page 8: ‘Women in Pakistan wait to vote’ by DFID - UK Department for International Development, http://www.flickr.com/photos/dfid/8735821208/ Licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0. -

2020 09 30 USG Southern Africa Fact Sheet #3

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 Southern Africa – Regional Disasters SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 10.5 765,000 5.4 1.7 320,000 MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Food- Estimated Confirmed Estimated Food-Insecure Estimated Severely Estimated Number Insecure Population in COVID-19 Cases in Population in Rural Food-Insecure of IDPs in Southern Africa Southern Africa Zimbabwe Population in Malawi Cabo Delgado IPC – Sept. 2020 WHO – Sept. 30, 2020 ZimVAC – Sept. 2020 IPC – Sept. 2020 WFP – Sept. 2020 Increasing prevalence of droughts, flooding, and other climatic shocks has decreased food production in Southern Africa, extending the agricultural lean season and exacerbating existing humanitarian needs. The COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures have worsened food insecurity and disrupted livelihoods for urban and rural households. USG partners delivered life-saving food, health, nutrition, protection, shelter, and WASH assistance to vulnerable populations in eight Southern African countries during FY 2020. TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA1,2 $202,836,889 For the Southern Africa Response in FY 2020 State/PRM3 $19,681,453 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 6 Total $222,518,3424 1USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 Total USAID/BHA funding includes non-food humanitarian assistance from the former Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) and emergency food assistance from the former Office of Food for Peace (USAID/FFP). 3 U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 4 This total includes approximately $30,914,447 in supplemental funding through USAID/BHA and State/PRM for COVID-19 preparedness and response activities.