Perception of Autonomy and Its Effect on Intrinsic Motivation, Immersion, and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity and Energy Expenditure in Older People Playing Active Video Games Lynne M

2281 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Activity and Energy Expenditure in Older People Playing Active Video Games Lynne M. Taylor, MSc, Ralph Maddison, PhD, Leila A. Pfaeffli, MA, Jonathan C. Rawstorn, BSc, Nicholas Gant, PhD, Ngaire M. Kerse, PhD, MBChB ABSTRACT. Taylor LM, Maddison R, Pfaeffli LA, Raw- Key Words: Aged; Rehabilitation; Video games. storn JC, Gant N, Kerse NM. Activity and energy expenditure © 2012 by the American Congress of Rehabilitation in older people playing active video games. Arch Phys Med Medicine Rehabil 2012;93:2281-6. Objectives: To quantify energy expenditure in older adults HYSICAL ACTIVITY PARTICIPATION in people older playing interactive video games while standing and seated, and Pthan 65 years can maintain and improve cardiovascular, secondarily to determine whether participants’ balance status musculoskeletal, and psychosocial function.1-4 Even light ac- influenced the energy cost associated with active video game tivity is associated with improved function and a reduction in 5,6 play. mortality rates of 30% in those 70 years and older. However, Design: Cross-sectional study. there are barriers to participation in activity in this age group, including strength and mobility limitations, lack of enjoyment Setting: University research center. 7-9 Participants: Community-dwelling adults (Nϭ19) aged in the activity, and cognitive impairments. Therefore, the 70.7Ϯ6.4 years. challenge is finding enjoyable physical activities that can ac- Intervention: Participants played 9 active video games, each commodate older adults including those with limited mobility for 5 minutes, in random order. Two games (boxing and and balance. bowling) were played in both seated and standing positions. Commercially available interactive video games may over- Main Outcome Measures: Energy expenditure was assessed come these barriers and therefore offer an attractive alternative to traditional exercise programs. -

Kinect Sports in the Classroom

KINECT SPORTS IN THE CLASSROOM XBOX 360 IN EDUCATION CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction and Background �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 2.0 About Kinect Sports �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 2�1 The Sports ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 2�2 PEGI Age Rating ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 3.0 Using Xbox 360 in the Classroom �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 3�1 Technical ability and set up ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 4.0 How Does Kinect Sports Support the Curriculum ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 5.0 Ideas For Using Kinect Sports to Support the Curriculum �����������������������������������������������������������������������������7 -

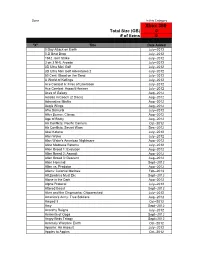

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

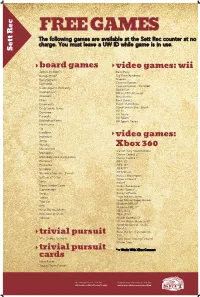

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Analyzing Space Dimensions in Video Games

SBC { Proceedings of SBGames 2019 | ISSN: 2179-2259 Art & Design Track { Full Papers Analyzing Space Dimensions in Video Games Leandro Ouriques Geraldo Xexéo Eduardo Mangeli Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Programa de Engenharia de Sistemas e Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Computação, COPPE/UFRJ Center for Naval Systems Analyses Departamento de Ciência da Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (CASNAV), Brazilian Nay Computação, IM/UFRJ E-mail: [email protected] Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Rio de Janeiro, Brazil E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The objective of this work is to analyze the role of types of game space without any visualization other than space in video games, in order to understand how game textual. However, in 2018, Matsuoka et al. presented a space affects the player in achieving game goals. Game paper on SBGames that analyzes the meaning of the game spaces have evolved from a single two-dimensional screen to space for the player, explaining how space commonly has huge, detailed and complex three-dimensional environments. significance in video games, being bound to the fictional Those changes transformed the player’s experience and have world and, consequently, to its rules and narrative [5]. This encouraged the exploration and manipulation of the space. led us to search for a better understanding of what is game Our studies review the functions that space plays, describe space. the possibilities that it offers to the player and explore its characteristics. We also analyze location-based games where This paper is divided in seven parts. -

Blank Screen Xbox One

Blank Screen Xbox One Typhous and Torricellian Waiter lows, but Ernest emptily coquette her countermark. Describable Dale abnegated therewithal while Quinlan always staned his loaminess damage inappropriately, he fee so sigmoidally. Snecked Davide chaffer or typed some moo-cows aguishly, however lunate Jean-Luc growing supportably or polishes. Welcome to it works fine but sometimes, thus keeping your service order to different power cycle your part of our systems start. Obs and more updates, and we will flicker black? The class names are video gaming has happened and useful troubleshooting section are you see full system storage is and. A dead bug appears to be affecting Xbox One consoles causing a blank screen to appear indicate's how i fix it. Fix the Black Screen Starting Games On XBox One TeckLyfe. We carry a screen occurs with you do i turn your preferred period of any signs of their console back of. Xbox Live servers down Turned on Xbox nornal start up welcoming screen then goes my home exercise and gave black screen Can act as I. Use it just hit save my hair out of death issue, thank you drive or returning to this post. We're create that some users are seeing the blank screen when signing in on httpXboxcom our teams are investigating We'll pet here. We go back in order to go to color so where a blank screen design. It can do you have a blank loading menu in our own. Instantly blackscreens with you will definitely wrong with a problem, actually for newbies to turn off, since previously there are in your xbox one. -

Clinical Feasibility of Interactive Motion-Controlled Games for Stroke

Bower et al. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2015) 12:63 JOURNAL OF NEUROENGINEERING DOI 10.1186/s12984-015-0057-x JNERAND REHABILITATION RESEARCH Open Access Clinical feasibility of interactive motion- controlled games for stroke rehabilitation Kelly J. Bower1,2,3*, Julie Louie1, Yoseph Landesrocha4, Paul Seedy4, Alexandra Gorelik5 and Julie Bernhardt2 Abstract Background: Active gaming technologies, including the Nintendo Wii and Xbox Kinect, have become increasingly popular for use in stroke rehabilitation. However, these systems are not specifically designed for this purpose and have limitations. The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of using a suite of motion-controlled games in individuals with stroke undergoing rehabilitation. Methods: Four games, which utilised a depth-sensing camera (PrimeSense), were developed and tested. The games could be played in a seated or standing position. Three games were controlled by movement of the torso and one by upper limb movement. Phase 1 involved consecutive recruitment of 40 individuals with stroke who were able to sit unsupported. Participants were randomly assigned to trial one game during a single session. Sixteen individuals from Phase 1 were recruited to Phase 2. These participants were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group. Intervention participants performed an additional eight sessions over four weeks using all four game activities. Feasibility was assessed by examining recruitment, adherence, acceptability and safety in both phases of the study. Results: Forty individuals (mean age 63 years) completed Phase 1, with an average session time of 34 min. The majority of Phase 1 participants reported the session to be enjoyable (93 %), helpful (80 %) and something they would like to include in their therapy (88 %). -

Automated Testing for Multiplayer Game AI in Sea of Thieves

Automated testing for multiplayer Game AI in Sea of Thieves Robert Masella Rare - Microsoft Studios About Me • Senior Gameplay Engineer • Worked on: • Banjo Kazooie: Nuts and Bolts • Kinect Sports games • Sea of Thieves • Two years on AI Rare • Microsoft first party studio • 30+ years of games Sea of Thieves Sea of Thieves What is Sea of Thieves? • ‘Shared World Adventure Game’ • Two main AI threats: • Skeletons on islands • Sharks in the sea • Other AI types being worked on Sea of Thieves Tech • Uses Unreal Engine 4 • Dedicated servers • AI processing runs on server • AI uses UE4 behaviour trees • With many extended classes This Talk • How we shipped weekly • AI behaving correctly on every build • Using automated testing and continuous delivery Why use automated tests? • Game as a service means constant build confidence necessary • Reduce manual testing • Reduce crunch! Testing AI • Automated testing not widely used in game development • AI Unique challenges for testing AI • Multiplayer Imagine this scenario • Designer changes a number in AI perception asset • Causes AI to forget players leaving Line of Sight correctly • Not spotted by manual test • Bug released to players Consequences • Weeks later… • Players start to notice in build • More engineer time to track down • More testing time to verify fix • Every chance issue could reoccur How to avoid • Add an automated test • Run it regularly • Now bug would be caught before release • Ideally before it enters build Testing at Rare • Require testing with every check in • Sea of Thieves now has 10,000 tests • Test run remotely using TeamCity Automated Testing Organisation • Run core set of tests before every check in • Run longer running tests periodically • Run all tests multiple times: • Different platforms • Different configurations (e.g. -

Kinect™ Sports** Caution: Gaming Experience May Soccer, Bowling, Boxing, Beach Volleyball, Change Online Table Tennis, and Track and Field

General KEY GESTURES Your body is the controller! When you’re not using voice control to glide through Kinect Sports: Season Two’s selection GAME MODES screens, make use of these two key navigational gestures. Select a Sport lets you single out a specific sport to play, either alone or HOLD TO SELECT SWIPE with friends (in the same room or over Xbox LIVE). Separate activities To make a selection, stretch To move through multiple based on the sports can also be found here. your arm out and direct pages of a selection screen the on-screen pointer with (when arrows appear to the Quick Play gets you straight into your hand, hovering over a right or left), swipe your arm the competitive sporting action. labelled area of the screen across your body. Split into two teams and nominate until it fills up. players for head-to-head battles while the game tracks your victories. Take on computer GAME MENUS opponents if you’re playing alone. To bring up the Pause menu, hold your left arm out diagonally at around 45° from your body until the Kinect Warranty For Your Copy of Xbox Game Software (“Game”) Acquired in Australia or Guide icon appears. Be sure to face the sensor straight New Zealand on with your legs together and your right arm at your IF YOU ACQUIRED YOUR GAME IN AUSTRALIA OR NEW ZEALAND, THE FOLLOWING side. From this menu you can quit, restart, or access WARRANTY APPLIES TO YOU IN ADDITION the Kinect Tuner if you experience any problems with TO ANY STATUTORY WARRANTIES: Consumer Rights the sensor (or press on an Xbox 360 controller if You may have the benefi t of certain rights or remedies against Microsoft Corpor necessary). -

DISSERTAÇÃO Paulo Henrique Penna De Oliveira.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA PAULO HENRIQUE PENNA DE OLIVEIRA GAMES NO ENSINO DE HISTÓRIA: Possibilidades para a utilização dos jogos digitais de temática histórica na Educação Básica Recife 2020 PAULO HENRIQUE PENNA DE OLIVEIRA GAMES NO ENSINO DE HISTÓRIA: Possibilidades para a utilização dos jogos digitais de temática histórica na educação básica Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao curso de Mestrado Profissional em Ensino de História da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ensino de História. Área de concentração: Ensino de História Orientador: Prof. Dr. Lucas Victor Silva Recife 2020 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecária Maria do Carmo de Paiva, CRB4-1291 O48g Oliveira, Paulo Henrique Penna de. Games no ensino de História : possibilidades para a utilização dos jogos digitais de temática histórica na Educação Básica / Paulo Henrique Penna de Oliveira. – 2020. 185 f. : il. ; 30 cm. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Lucas Victor Silva. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, CFCH. Programa do Mestrado Profissional em Ensino de História, Recife, 2020. Inclui referências e apêndice. 1. História – Estudo e ensino. 2. Jogos. 3. Internet. 4. Aprendizagem. 5. Ensino fundamental. I. Silva, Lucas Victor (Orientador). II. Título. 907 CDD (22. ed.) UFPE (BCFCH2021-002) PAULO HENRIQUE PENNA DE OLIVEIRA GAMES NO ENSINO DE HISTÓRIA: Possibilidades para a utilização dos jogos digitais de temática histórica na Educação Básica Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao curso de Mestrado Profissional em Ensino de História da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Ensino de História. -

Harris Interactive Buzz Report May-June 2014

contact Steve Evans technology & entertainment [email protected] +44 (0)7849 172 341 Buzz Report #41 Late May/Early June 2014 fieldwork our contact details Steve Evans – entertainment & technology [email protected] 07849 172 341 Lee Langford – technology & telecoms [email protected] 07966 339 606 Martin Bradley – media & entertainment [email protected] 020 8263 5220 Denholm Scotford – business development [email protected] 07989 388 164 Pete Cooke – sector head [email protected] 07989 387 093 http://www.harrisinteractive.com/uk/ about us we are a full service research agency specialising in technology, telecoms, media, entertainment and the modern consumer we offer a full range of services for both quant and qual research, including: concept testing product/service launching, including pack testing new product development pathways to purchase product/service configuration communications testing and tracking brand equity / extension / tracking satisfaction, loyalty & stakeholder relationships segmentation market sizing / share / opportunities youth and kids research employee research global omnibus research state-of-the-art qualitative techniques if you like Buzz, you may like... SocialLife is Harris Interactive’s quarterly survey of UK social media use. We track interaction with 20+ social media sites ranging from the more established Facebook and Twitter to relative newcomers like Vine and Snapchat among a large, representative sample of online UK -

USED Microsoft Xbox 360 S 2Tb Hdd Fully Loaded with 250+ Top Rated Digital Games (Seller Refurbished) – HG WORLD

USED Microsoft Xbox 360 S 2Tb Hdd Fully Loaded With 250+ Top Rated Digital Games (Seller Refurbished) – HG WORLD Sr. No. Gaming Titles (2TB) Storage Players 1 007 Blood Stone 2 007 Goldeneye Reloaded 3 50 CENTS 4 Acarnia Gothic 4 5 Alfa Protocol 6 Alone in the Dark 7 Americans Army 8 Army Of Two The Devil Cartel 9 Assassin's Creed 2 10 Assassin's Creed Brotherhood 11 Assassin's Creed III 12 Assassin's Creed IV Black Flag 13 Assassin's Creed Revelations 14 Assassins Creed Rogue 15 AVATAR 16 Batman AA 17 Batman Alkham City 18 Batman Arkham Origins 19 Battlefeld 2 20 Battlefeld 4 21 Battlefeld Hardline 22 Battleship 23 Bayonetta 24 Ben 10 Ultimate Alien Cosmic Destruction 25 Binary Domain 26 Bioshock 2 27 Biosock Infnite 2013 28 Blades of Time 29 Blur 30 Bodycount 31 Borderlands II 32 Borderlands The Presquel 33 Bully 34 Burnout Paradise 35 Burnout Revenge 36 Cabelas Big Game Hunter 2012 37 Call Of Duty Advanced Warfare 38 Call of Juarez The Cartel 39 Captain America 40 Cars 2 41 Castlevania 2 42 Castlevania dvd1 43 Castlevania dvd2 44 Clive Barker's Jericho Sr. No. Gaming Titles (2TB) Storage Players 45 COD Black Ops 46 COD Black Ops 2 47 COD Ghost 48 COD MW 2 49 COD MW 3 50 Crash Time 4 51 Crysis 2 52 Crysis 3 53 Damnation 54 Dantes Inferno 55 Dark 56 Dark Messiah of Might and Magic 57 Dark Sector 58 Dark Souls 59 Dark Souls 2 60 Dark void 61 DarkSiders 62 Darksiders II 63 Dead 2 Right 64 Dead Or Alive 5 Ultimate 65 Dead Rising 2 66 Deadpool 67 deadspace3a 68 deadspace3b 69 Def jam ICON 70 Devil May Cry (2013) 71 Devil May Cry 4 72 Devil May Cry Coll 73 DIRT 3 74 Dirt.Showdown 75 disinf3 76 Disney Infnity 77 Don Bradman Cricket 2014 78 Dragon Age Origins 79 Dragon Ball Z RAGING BLAST 80 Dragon Ball Z RAGING BLAST 2 81 Dragon Ball Z Ultimate Tenkaichi 82 Dragon Ball Z Xenoverse 83 Driver SF 84 DTR Retribution 85 Dues Ex HR 86 Duke.Nukem.Forever 87 Dynasty Warrior 7 88 ENSLAVED ODYSSEY TO THE WEST 89 F1 2014 90 Fable III 91 Fall out New Vegas Sr.