Looking for Nuns: a Prosopographical Study of Scottish Nuns in the Later Middle Ages*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

Spinning Scotland Abstr

1 ABSTRACTS FOR SPINNING SCOTLAND CONFERENCE GLASGOW UNIVERSITY - 13 th SEPTEMBER 2008 2 PANEL 1: ISLAND POETRY – ON THE FRINGE? Iain MacDonald – Linden J Bicket – Emma Dymock 9.30 – 11am Iain MacDonald The Very Heart of Beyond: Gaelic Nationalism and the Work of Fionn Mac Colla. The work of Fionn Mac Colla (Thomas Douglas Macdonald) examines the development of religious ideas and politics on Scottish society. He was primarily concerned with the representation of Scottish Gaelic and the cultural implications for Scotland with the erosion and re-establishment of Gaelic culture and identity in the industrialising modern era. These themes are most comprehensively explored in his best-known works, The Albannach (1932) and And The Cock Crew (1945) J.L. Broom's claim that MacColla's obsession with Calvinism's influence over Scotland had 'reached such proportions as to have distorted his artistic priorities' has influenced attitudes and encouraged lazy critical reception of the writer. It is my contention that MacColla's contribution to the developing 'Scottish Literary Renaissance' of the 1920s and 30s can be described as major, even if, at times, deserved critical reception has been thwarted. Mac Colla's work is primarily concerned with Scottish Gaelic culture, and its history. Although his fictional work concentrates on Gaelic communities in the central Highlands, Mac Colla spent 20 years living and teaching in the Hebrides. In this paper I will demonstrate that Mac Colla's work and themes are interwoven with his own experiences of the Gaelic community. I will also examine the title of this panel with reference to Fionn Mac Colla. -

A Colonial Scottish Jacobite Family

A COLONIAL SCOTTISH JACOBITE FAMILY THE ESTABLISHMENT IN VIRGINIA OF A BRANCH OF THE HUM-ES of WEDDERBURN Illustrated by Letters and Other Contemporary Documents By EDGAR ERSKINE HUME M. .A... lL D .• LL. D .• Dr. P. H. Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Member of the Virginia and Kentucky Historical Societies OLD DoKINION PREss RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 1931 COPYRIGHT 1931 BY EDGAR ERSKINE HUME .. :·, , . - ~-. ~ ,: ·\~ ·--~- .... ,.~ 11,i . - .. ~ . ARMS OF HUME OF WEDDERBURN (Painted by Mr. Graham Johnston, Heraldic Artist to the Lyon Office). The arms are thus recorded in the Public ReJ?:ister of all Arms and Bearings in Scotland (Court of the Lord Lyon King of Arms) : Quarterly, first and fourth, Vert a lion rampant Argent, armed and langued Gules, for Hume; second Argent, three papingoes Vert, beaked and membered Gules, for Pepdie of Dunglass; third Argent, a cross enirrailed Azure for Sinclair of H erdmanston and Polwarth. Crest: A uni corn's head and neck couped Argent, collared with an open crown, horned and maned Or. Mottoes: Above the crest: Remember; below the shield: True to the End. Supporters: Two falcons proper. DEDICATED To MY PARENTS E. E. H., 1844-1911 AND M. S. H., 1858-1915 "My fathers that name have revered on a throne; My fathers have fallen to right it. Those fathers would scorn their degenerate son, That name should he scoffingly slight it . " -BORNS. CONTENTS PAGE Preface . 7 Arrival of Jacobite Prisoners in Virginia, 1716.......... 9 The Jacobite Rising of 1715. 10 Fate of the Captured Jacobites. 16 Trial and Conviction of Sir George Hume of Wedder- burn, Baronet . -

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Printed Draft Minutes PDF 138 KB

MINUTES of Meeting of the CHEVIOT AREA PARTNERSHIP held in ASSEMBLY ROOM, JEDBURGH GRAMMAR SCHOOL, JEDBURGH on Wednesday, 29 January 2020 at 6.30 pm Present:- Councillors S. Hamilton (Chairman), E. Robson, S. Scott, T. Weatherston together with 16 Representatives of Partner Organisations, Community Councils and Members of the Public. Apologies: - Councillors Mountford and Brown. In attendance: - Strategic Community Engagement Officer, Locality Development Co- ordinator (Jan Pringle), Democratic Services Officer (F. Henderson). Members of the Public: - 16 WELCOME AND INTRODUCTIONSThe Chairman welcomed everyone to the Cheviot Area Partnership and thanked the Community Councils, Partners and local organisations for their attendance, and for participating and putting forward ideas. 2.0 FEEDBACK FROM MEETING ON 25 SEPTEMBER 2019 2.1 The minute of the meeting of the Cheviot Area Partnership held on 25 September 2019 had been circulated. A summary of the discussion on Community Transport: Solutions and Actions was attached as an appendix to the Minute. 3.0 TRANSPORT UPDATE 3.1 Following the presentation given at the meeting on 25 September 2029, Timothy Stephenson, Transport Manager was in attendance to give a verbal update on Transport Planning. It was explained that the Council had a statutory obligation to transport Pupils and not to provide Local Bus Services. Subsidies on local bus services (LBS) cost £1.5m per annum and moved 1m travellers and as with other Local Authorities budgets of the LBS were always being reviewed. Savings made in 2018 totalled £200k and were based on data collected on-bus and passenger trends, providing alternatives and some innovative thinking. Savings in 2019 of £85k were already secured without further cuts to bus services and £165k of budget savings were needed in 2020. -

Cheviot Area Forum Wednesday 26 November 2014

CHEVIOT AREA FORUM WEDNESDAY 26 NOVEMBER 2014 A MEETING of the CHEVIOT AREA FORUM will be held in the HOWDENBURN PRIMARY SCHOOL, LOTHIAN ROAD, JEDBURGH on WEDNESDAY 26 NOVEMBER 2014 at 6.30pm. J. J. WILKINSON Clerk to the Council 19 November 2014 BUSINESS 1. Welcome and Introductions 2. Apologies for Absence. 3. Order of Business. 4. Declarations of Interest. 5. Minute. Minute of the meeting of Cheviot Area Committee of 4 June 2014 2 mins to be noted. (Copy attached.) 6. Police Force of Scotland - 'J' Division Spotlight. Update report by 20 mins Police Inspector detailing ongoing work and initiatives in the Cheviot area. 7. Amey - Scotland South East Unit. Mr Stephen Kitt will be present to 20 mins update the Forum and answer questions. 8. Scottish Fire & Rescue Service. Update report detailing ongoing work 20 mins and initiatives in the Cheviot Area. 9. Revenue, Capital and SB Local Works. Consider update on the progress 10 mins of the planned programme of revenue and capital works, the work undertaken by the SB Local Squad and the proposed SB Local Small Schemes for the current financial year in the Cheviot Area. 10. Local Public Holidays 2015. Consider proposed local public holiday dates 10 mins for 2015 in Jedburgh and Kelso. (Copy list attached.) 11. Open Questions. Opportunity for members of the public to raise any 10 mins issues not included on the agenda. 12. Community Council Spotlight. Consider updates and matters of interest 10 mins to Community Councils. (a) Oxnam Road, Jedburgh (b) Skiprunningburn Flood Protection 13. Any Other Items Previously Circulated. -

Borders Family History Society Sales List February 2021

Borders Family History Society www.bordersfhs.org.uk Sales List February 2021 Berwickshire Roxburghshire Census Transcriptions 2 Census Transcriptions 8 Death Records 3 Death Records 9 Monumental Inscriptions 4 Monumental Inscriptions 10 Parish Records 5 Parish Records 11 Dumfriesshire Poor Law Records 11 Parish Records 5 Prison Records 11 Edinburghshire/Scottish Borders Selkirkshire Census Transcriptions 5 Census Transcriptions 12 Death Records 5 Death Records 12 Monumental Inscriptions 5 Monumental Inscriptions 13 Peeblesshire Parish Records 13 Census Transcriptions 6 Prison Records 13 Death Records 7 Other Publications 14 Monumental Inscriptions 7 Maps 17 Parish Records 7 Past Magazines 17 Prison Records 7 Postage Rates 18 Parish Map Diagrams 19 Borders FHS Monumental Inscriptions are recorded by a team of volunteer members of the Society and are compiled over several visits to ensure accuracy in the detail recorded. Additional information such as Militia Lists, Hearth Tax, transcriptions of Rolls of Honour and War Memorials are included. Wherever possible, other records are researched to provide insights into the lives of the families who lived in the Parish. Society members may receive a discount of £1.00 per BFHS monumental inscription volume. All publications can be ordered through: online : via the Contacts page on our website www.bordersfhs.org.uk/BFHSContacts.asp by selecting Contact type 'Order for Publications'. Sales Convenor, Borders Family History Society, 52 Overhaugh St, Galashiels, TD1 1DP, mail to : Scotland Postage, payment, and ordering information is available on page 17 NB Please note that many of the Census Transcriptions are on special offer and in many cases, we have only one copy of each for sale. -

Communion Tokens of the Established Church of Scotland -Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries

V. COMMUNION TOKENS OF THE ESTABLISHED CHURCH OF SCOTLAND -SIXTEENTH, SEVENTEENTH, AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES. BY ALEXANDER J. S. BROOK, F.S.A. SCOT. o morn Ther s e familiawa e r objec Scotlann i t d fro e Reformatiomth n down to half a century ago than the Communion token, but its origin cannot be attributed to Scotland, nor was it a post-Reformation institution. e antiquitTh d universalitan y e toke th e unquestionable f ar no y . From very early times it is probable that a token, or something akin uses aln wa di l , toath-bounoit d secret societies. They will be found to have been used by the Greeks and Romans, whose tesserae were freely utilise r identifyinfo d gbeed ha thos no ewh initiated inte Eleusiniath o d othean n r kindred mysteries n thii d s an , s easilwa yy mannepavewa r thei e fo dth rr introduction e intth o Christian Church, where they wer e purposeth use r f excludinfo do e g the uninitiated and preventing the entrance of spies into the religious gatherings which were onl yselece opeth o tnt few. Afte persecutioe th r n cease whicho dt measurea n e i ,b y , ma thei e us r attributed, they would naturally continu e use b o distinguist do t e h between those who had a right to be present at meetings and those who had not. Tokens are unquestionably an old Catholic tradition, and their use Churce on t confiner countryy o no h an s o t wa d. -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource. -

Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318

University of Huddersfield Repository Gledhill, Jonathan Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318 Original Citation Gledhill, Jonathan (2012) Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318. In: England and Scotland at War, c.1296-c.1513. Brill, Leiden, pp. 157-182. ISBN 9789004229822 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/14669/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ 7 Locality and Allegiance: English Lothian, 1296-1318 JONATHAN D. GLEDHILL The enforced abdication of King John in July 1296 and the consequent degrading of Scotland from an independent kingdom to a mere land of the English monarchy introduced a difficult political dualism into Scottish politics. The military conquest of Scotland meant that its barons and knights now had to decide whether to accept English claims to overlordship that were directly exercised through a colonial government, or continue to support a series of guardians who acted in King John’s name: a situation that lasted until the negotiated surrender of the guardian John Comyn of Badenoch at Strathord in 1304. -

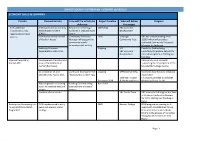

Cheviot Locality Action Plan – Updated 10/12/2019 Economy Skills & Learning

CHEVIOT LOCALITY ACTION PLAN – UPDATED 10/12/2019 ECONOMY SKILLS & LEARNING Priority Planned Activity How will the activity be Project timeline Who will deliver Progress delivered the project Seek additional Jedburgh Conservation Area Restoration of heritage 2019-2022 SBC Economic investment to help Regeneration Scheme buildings in Jedburgh town Development regenerate out town (CARS) centre centres. Community Refurbishment Community Enterprise 2020 Jedburgh SBC has secured funding from of the Port House Manager will support the Community Trust SOSEP which will provide a community to take dedicated Community Enterprise forward project activity Manager for Jedburgh. Jedburgh Economic Ongoing JCC Feasibility Studies being Regeneration Action Plan SBC Economic undertaken to explore options for Development the redevelopment of SBC legacy buildings Improve the existing Development of existing and Community Fund currently tourism offer new accommodation or supporting the development of the tourism Businesses Morebattle Heritage Centre. Co-ordination of, and Continued development of Ongoing MBTAG/Visit Kelso Visit Kelso local business led group between, Key Tourist Sites “Scotland Starts here” App established. Jedburgh Tourism CF support provided to Jedburgh December 2018 & Marketing Group Marketing Group for the Adjusting business opening Funding Currently being April 2019 hours to meet the needs of sourced from a range of visitors sources Creation of new events SBC Events Team SBC secured a Full stage of the Tour of Britain in the Scottish Borders for 2019, starting and finishing in Kelso Develop the Developing the DYW implemented in early 2020 Borders College DYW programme running for 4 Young Workforce (DYW) years and primary school years and has established strong Programme settings links with industry and schools.