Swans and Swan Lake: from Tchaikovsky to Matthew Bourne Bethany Nichol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Angel Cried out (1887) | Angel Vopiyashe 2:57

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893) All-Night Vigil, Op. 52 (1881) An Essay in Harmonizing liturgical chants Vsenoshchnoye bdeniye Opït garmonizatsiy bogosluzehbnïh pesnopeniy 1. Bless the Lord, O My Soul | Blagoslovi, dushe moya, Ghospoda 6:48 2. Kathisma: Blessed is the Man | Kafizma: Blazhen muzh 3:20 3. Lord, I Call | Ghospodi, vozzvah 0:58 4. Gladsome Light | Svete tihiy 2:25 5. Rejoice, O Virgin | Bogoroditse Devo 0:44 6. The Lord is God | Bog Ghospod 1:02 7. Praise the Name of the Lord | Hvalite imia Ghospodne 4:00 8. Blessed Art Thou, O Lord | Blagosloven yesi, Ghospodi 4:29 9. From My Youth | Ot yunosti moyeya 1:42 10. Having Beheld the Resurrection of Christ | Voskreseniye Hristovo videvshe 2:14 11. Common Katavasia: I Shall Open My Lips | Katavasiya raidovaya: Otverzu usta moya 5:17 12. Theotokion: Thou Art Most Blessed | Bogorodichen: Preblagoslovenna yesi 1:21 13. The Great Doxology | Velikoye slavosloviye 6:40 14. To Thee, the Victorious Leader | Vzbrannoy voyevode 0:55 15. Hymn in Honour of Saints Cyril and Methodius (1885) | Gimn v chest Sv. Kirilla i Mefodiya 2:44 16. A Legend, Op. 54 No. 5 (1883) | Legenda 3:12 17. Jurists’ Song (1885) | Pravovedcheskaya pesn 2:02 18. The Angel Cried Out (1887) | Angel vopiyashe 2:57 Latvian Radio Choir SIGVARDS KĻAVA, conductor he Latvian Radio Choir, led by Sigvards Kļava, presents a second album of sacred works by TPeter Tchaikovsky for choir. As with the first, its centrepiece is an extensive multi-movement composition – in this case, the All-Night Vigil. -

Waltz from the Sleeping Beauty

Teacher Workbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Jessica Nalbone .................................................................................2 Director of Education, North Carolina Symphony Information about the 2012/13 Education Concert Program ............................3 North Carolina Symphony Education Programs .................................................4 Author Biographies ..............................................................................................6 Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) .......................................................................................7 Oriental Festival March from Aladdin Suite, Op. 34 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) ..........................................................15 Symphony No. 39 in E-flat Major, K.543, Mvt. I or III (Movements will alternate throughout season) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) ..............................................................................28 “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk” from Children’s Corner, Suite for Orchestra Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) ..................................................................33 Waltz from The Sleeping Beauty Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) ...............................................................................44 “Dance of the Young Girls” from The Rite of Spring Loonis McGlohon (1921-2002) & Charles Kuralt (1924-1997) ..........................52 “North Carolina Is My Home” Richard Wagner (1813-1883) ..............................................................................61 Overture to Rienzi -

Download This Composer Profile Here

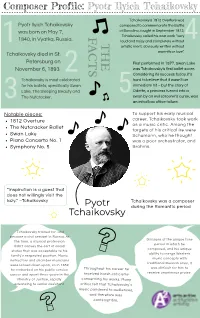

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon Du Diable

Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable Edited and Introduced by Robert Ignatius Letellier Cesare Pugni: Esmeralda and Le Violon du diable, Edited by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Edited and Introducted by Robert Ignatius Letellier and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3608-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3608-1 Cesare Pugni in London (c. 1845) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................... ix Esmeralda Italian Version La corte del miracoli (Introduzione) .......................................................................................... 2 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................. 5 Sposalizio di Esmeralda ............................................................................................................. 6 Allegro giusto............................................................................................................................ -

Miranda Weese Joins Boston Ballet As New Children's Ballet Master And

MEDIA CONTACTS: Jill Goddard, 617.456.6236, [email protected] Sarah Gledhill, 617.456.6264, [email protected] MIRANDA WEESE JOINS BOSTON BALLET AS NEW CHILDREN’S BALLET MASTER AND BOSTON BALLET SCHOOL FACULTY MEMBER FORMER PRINCIPAL DANCER WITH NEW YORK CITY BALLET AND PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET BRINGS WEALTH OF EXPERIENCE September 21, 2017 (BOSTON, MA) – Boston Ballet welcomes Miranda Weese, former principal dancer with New York City Ballet and Pacific Northwest Ballet, as the new Children’s Ballet Master. “I was always a big fan of Miranda Weese as a dancer and truly enjoyed her work onstage,” said Artistic Director Mikko Nissinen. “She is dedicated to teaching future generations of dancers and I am pleased to welcome her to the Boston Ballet family.” Weese will work with Boston Ballet School’s students for Company productions including this season’s Mikko Nissinen’s The Nutcracker (auditions for Boston Ballet School students begin Sep 23), Romeo & Juliet, The Sleeping Beauty, and La Sylphide. As a faculty member with Boston Ballet School, she will teach intermediate levels in the Classical Ballet Program and the female levels of the Pre-Professional Program. “Boston Ballet School students will learn and grow so much under Miranda’s tutelage,” said Margaret Tracey, Director of Boston Ballet School. “I am thrilled that she is joining our dedicated and hard-working team.” From San Bernardino, California, Weese trained at Laguna Dance Theatre and School of American Ballet. She danced with New York City Ballet from 1991 through 2007, as an apprentice, corps, soloist, and principal dancer. Her repertoire includes leading roles in George Balanchine’s Apollo, Concerto Barocco, Divertimento No. -

Don Quixote Press Release 2019

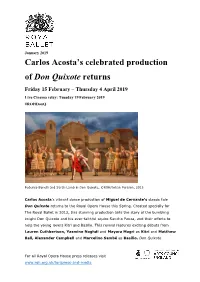

January 2019 Carlos Acosta’s celebrated production of Don Quixote returns Friday 15 February – Thursday 4 April 2019 Live Cinema relay: Tuesday 19 February 2019 #ROHDonQ Federico Bonelli and Sarah Lamb in Don Quixote, ©ROH/Johan Persson, 2013 Carlos Acosta’s vibrant dance production of Miguel de Cervante’s classic tale Don Quixote returns to the Royal Opera House this Spring. Created specially for The Royal Ballet in 2013, this stunning production tells the story of the bumbling knight Don Quixote and his ever-faithful squire Sancho Panza, and their efforts to help the young lovers Kitri and Basilio. This revival features exciting debuts from Lauren Cuthbertson, Yasmine Naghdi and Mayara Magri as Kitri and Matthew Ball, Alexander Campbell and Marcelino Sambé as Basilio. Don Quixote For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/for/press-and-media includes a number of spectacular solos and pas de deux as well as outlandish comedy and romance as the dashing Basilio steals the heart of the beautiful Kitri. Don Quixote will be live streamed to cinemas on Tuesday 19 February as part of the ROH Live Cinema Season. Carlos Acosta previously danced the role of Basilio in many productions of Don Quixote. He was invited by Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet, to re-stage this much-loved classic in 2013. Acosta’s vibrant production evokes sunny Spain with designs by Tim Hatley who has also created productions for the National Theatre and for musicals including Dreamgirls, The Bodyguard and Shrek. Acosta’s choreography draws on Marius Petipa’s 1869 production of this classic ballet and is set to an exuberant score by Ludwig Minkus arranged and orchestrated by Martin Yates. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

SWAN LAKE Dear Educators in the Winter Show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’S Student Performance Series (SPS) Students Will Be Treated to an Excerpt from Swan Lake

STUDENT PERFORMANCE SERIES STUDY GUIDE / Feburary 21, 2013 / Keller Auditorium / Noon - 1:00 pm, doors open at 11:30am SWAN LAKE Dear Educators In the winter show of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s Student Performance Series (SPS) students will be treated to an excerpt from Swan Lake. It is a quintessential ballet based on a heart-wrenching fable of true love heroically won and tragically Photo by Joni Kabana by Photo squandered. With virtuoso solos and an achingly beautiful score, it is emblematic of the opulent grandeur of the greatest of all 19th-Century story ballets. This study guide is designed to help teachers prepare students for their trip to the theatre where they will see Swan Lake Act III. In this Study Guide we will: • Provide the entire synopsis for Christopher Stowell’sSwan Lake, consider some of the stories that inspired the ballet, Principal Dancer Yuka Iino and Guest Artist Ruben Martin in Christopher and touch on its history Stowell’s Swan Lake. Photo by Blaine Truitt Covert. • Look closely at Act III • Learn some facts about the music for Swan Lake • Consider the way great dances are passed on to future generations and compare that to how students come to know other great works of art or literature • Describe some ballet vocabulary, steps and choreographic elements seen in Swan Lake • Include internet links to articles and video that will enhance learning At the theatre: • While seating takes place, the audience will enjoy a “behind the scenes” look at the scenic transformation of the stage • Oregon Ballet Theatre will perform Act III from Christopher Stowell’s Swan Lake where Odile’s evil double tricks the Prince into breaking his vow of love for the Swan Queen. -

Copyright © 2012 by Martin M. Van Brauman THEOLOGICAL AND

THEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL ANTI-SEMITISM MANIFESTING INTO POLITICAL ANTI-SEMITISM MARTIN M. VAN BRAUMAN The Lord appeared to Solomon at night and said to him I have heard your prayer and I have chosen this place to be a Temple of offering for Me. If I ever restrain the heavens so that there will be no rain, or if I ever command locusts to devour the land, or if I ever send a pestilence among My people, and My people, upon whom My Name is proclaimed, humble themselves and pray and seek My presence and repent of their evil ways – I will hear from Heaven and forgive their sin and heal their land. 2 Chronicles 7:12-14. Political anti-Semitism represents the ideological weapon used by totalitarian movements and pseudo-religious systems.1 Norman Cohn in Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World-Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion wrote that during the Nazi years “the drive to exterminate the Jews sprang from demonological superstitions inherited from the Middle Ages.”2 The myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy developed out of demonology and inspired the pathological fantasy of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was used to stir up the massacres of Jews during the Russian civil war and then was adopted by Nazi ideology and later by Islamic theology.3 Most people see anti-Semitism only as political and cultural anti-Semitism, whereas the hidden, most deeply rooted and most dangerous source of the evil has been theological anti-Semitism stemming historically from Christian dogma and adopted by and intensified with -

Iolanta Bluebeard's Castle

iolantaPETER TCHAIKOVSKY AND bluebeard’sBÉLA BARTÓK castle conductor Iolanta Valery Gergiev Lyric opera in one act production Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, Mariusz Treliński based on the play King René’s Daughter set designer by Henrik Hertz Boris Kudlička costume designer Bluebeard’s Castle Marek Adamski Opera in one act lighting designer Marc Heinz Libretto by Béla Balázs, after a fairy tale by Charles Perrault choreographer Tomasz Wygoda Saturday, February 14, 2015 video projection designer 12:30–3:45 PM Bartek Macias sound designer New Production Mark Grey dramaturg The productions of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle Piotr Gruszczyński were made possible by a generous gift from Ambassador and Mrs. Nicholas F. Taubman general manager Peter Gelb Additional funding was received from Mrs. Veronica Atkins; Dr. Magdalena Berenyi, in memory of Dr. Kalman Berenyi; music director and the National Endowment for the Arts James Levine principal conductor Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and Fabio Luisi Teatr Wielki–Polish National Opera The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of PETER TCHAIKOVSKY’S This performance iolanta is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored conductor by Toll Brothers, Valery Gergiev America’s luxury in order of vocal appearance homebuilder®, with generous long-term marta duke robert support from Mzia Nioradze Aleksei Markov The Annenberg iol anta vaudémont Foundation, The Anna Netrebko Piotr Beczala Neubauer Family Foundation, the brigit te Vincent A. Stabile Katherine Whyte Endowment for Broadcast Media, l aur a and contributions Cassandra Zoé Velasco from listeners bertr and worldwide. Matt Boehler There is no alméric Toll Brothers– Keith Jameson Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall today. -

Historie a Vývoj Baletní Scény Mariinského Divadla

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra ruského jazyka a literatury Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Studijní program: N7504 – Učitelství pro střední školy Studijní obor: Učitelství pro střední školy – základy společenských věd Učitelství pro střední školy – ruský jazyk a literatura Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jaroslav Sommer Oponent práce: prof. PhDr. Ivo Pospíšil, DrSc. Hradec Králové 2020 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala (pod vedením vedoucího diplomové práce) samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. V Hradci Králové dne … ………………………… Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala svému vedoucímu panu Mgr. Jaroslavu Sommerovi za odborné vedení a cenné rady při vypracovávání diplomové práce. Dále děkuji paní Mgr. Jarmile Havlové za pomoc při korektuře gramatické stránky práce. Anotace PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla. Hradec Králové: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 s. Diplomová práce. Práce se zaměřuje na historii a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla po současnost. Věnuje se také nejslavnějším osobnostem a inscenacím baletní scény Mariinského divadla v Petrohradě. Klíčová slova: balet, divadlo, Petrohrad, umění, Leningrad, Kirovovo divadlo opery a baletu, Mariinské divadlo. Annotation PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. History and Development of the Mariinsky Ballet. Hradec Králové: Faculty of Education, University of Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 pp. Diploma Dissertation Degree Thesis. The thesis focuses on the history and development of the ballet stage of the Mariinsky Theatre up to the present. It is also dedicated to the most outstanding personalities and stagings of the Mariinsky Theatre in Petersburg. Keywords: ballet, theatre, Saint Petersburg, art, Leningrad, Kirov Theatre, The Mariinsky Theatre. -

October 1936) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 10-1-1936 Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 54, Number 10 (October 1936)." , (1936). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/849 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE zJxtusic ^Magazine ©ctefoer 1936 Price 25 Cents ENSEMBLES MAKE INTERESTING RECITAL NUVELTIES PIANO Pianos as are Available The Players May Double-Up on These Numbers Employing as Many By Geo. L. Spaulding Curtis Institute of Music Price. 40 cents DR. JOSEF HOFMANN, Director Faculty for the School Year 1936-1937 Piano Voice JOSEF HOFMANN, Mus. D. EMILIO de GOGORZA DAVID SAPERTON HARRIET van EMDEN ISABELLE VENGEROVA Violin Viola EFREM ZIMBALIST LEA LUBOSHUTZ Dr. LOUIS BAILLY ALEXANDER HILSBERG MAX ARONOFF RUVIN HEIFETZ Harp Other Numbers for Four Performers at One Piamo Violincello CARLOS SALZEDO Price Cat. No. Title and Composer Cat. No. Title and Composer 26485 Song of the Pinas—Mildred Adair FELIX SALMOND Accompanying and $0.50 26497 Airy Fairies—Geo.