The Link Is Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Ground up the First Fifty Years of Mccain Foods

CHAPTER TITLE i From the Ground up the FirSt FiFty yearS oF mcCain FoodS daniel StoFFman In collaboratI on wI th t ony van l eersum ii FROM THE GROUND UP CHAPTER TITLE iii ContentS Produced on the occasion of its 50th anniversary Copyright © McCain Foods Limited 2007 Foreword by Wallace McCain / x by All rights reserved. No part of this book, including images, illustrations, photographs, mcCain FoodS limited logos, text, etc. may be reproduced, modified, copied or transmitted in any form or used BCE Place for commercial purposes without the prior written permission of McCain Foods Limited, Preface by Janice Wismer / xii 181 Bay Street, Suite 3600 or, in the case of reprographic copying, a license from Access Copyright, the Canadian Toronto, Ontario, Canada Copyright Licensing Agency, One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario, M6B 3A9. M5J 2T3 Chapter One the beGinninG / 1 www.mccain.com 416-955-1700 LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Stoffman, Daniel Chapter Two CroSSinG the atlantiC / 39 From the ground up : the first fifty years of McCain Foods / Daniel Stoffman For copies of this book, please contact: in collaboration with Tony van Leersum. McCain Foods Limited, Chapter Three aCroSS the Channel / 69 Director, Communications, Includes index. at [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-9783720-0-2 Chapter Four down under / 103 or at the address above 1. McCain Foods Limited – History. 2. McCain, Wallace, 1930– . 3. McCain, H. Harrison, 1927–2004. I. Van Leersum, Tony, 1935– . II. McCain Foods Limited Chapter Five the home Front / 125 This book was printed on paper containing III. -

The Sculpture Center 1834 East 123Rd Street Cleveland, Ohio 44106-1910

THE SCULPTURE CENTER 1834 EAST 123RD STREET CLEVELAND, OHIO 44106-1910 November 15, 2004 Contact: Deirdre Lauer, Director of Exhibitions & Public Programs 216-229-6527 Significant Sculpture Presented in Private Collections Exhibition The Sculpture Center presents Private Collections, December 17, 2004 – January 21, 2005, a rare opportunity to view an exciting display of impressive sculpture culled from Cleveland’s most significant private collections, that includes works by internationally recognized sculptors, members of The Cleveland School and significant local artists. Many of these works have never been publicly exhibited before. The Sculpture Center, best known for its exhibitions of emerging artists, offers Private Collections to place the work of emerging artists in context with an informed look at what are considered more traditional forms. Private Collections will prompt discussion of what makes a lasting artistic impression and what led certain artists to success in their careers. Generous private collectors have loaned two- and three-dimensional works by sculptors with international reputations such as Isamu Noguchi, Claes Oldenburg, Arnaldo Pomodoro and Mark di Suvero, among others, as well as pieces by venerated Cleveland artists such as Viktor Schreckengost, William McVey, Edris Eckhardt and David E. Davis. Collectors have also loaned valuable works by local artists David Deming, Robert Thurmer, Terry Durst, Bruce Biro and Andrew Chakalis. The exhibition will open December 17, 2004 and run through January 21, 2005. The opening night reception will take place December 17 from 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm and will feature a gallery talk by the curator, noted art historian Professor Edward J. Olszewski. The cost for this special reception is $15 per person or $25 per couple. -

History's Future

Winter 2003 ture the multigenera- American and East Asian history, to tional change that name a few. Recent faculty publica- shapes the Los tions span topics from the history of Angeles immigrant household government in America to communities. Down the study of medieval women. the corridor, Philip “The momentum of the history Ethington documents department is being fueled by some the timeless transfor- outstanding new faculty members, a mation of Los Angeles’ growing list of external collaborations people, landscapes and and the smart use of technology,” architecture through says College Dean Joseph Aoun. streaming media and “We are positioned to do some great digital panoramic pho- things in the 21st century.” tos. Meanwhile, medievalist Lisa Tales of the West Bitel—a recent The College boasts a strong con- Guggenheim Fellow— figuration of late 19th- and early collaborates with 20th-century American historians, scholars in European and is a pre-eminent center for libraries in a quest to examining the American West. make archives that At the forefront is University detail women’s first Professor and California State religious communities Librarian Kevin Starr, whose book easily accessible via the series chronicling California history Internet. Another col- and the American dream has gained league, Steven Ross, worldwide popularity. partners with the USC Other historians, such as Sanchez Center for Scholarly and Lon Kurashige, study Latino and Technology to docu- Asian immigration patterns to better ment how film shaped understand how American society has ideas about class and organized and changed through time. power in the 20th cen- Indeed, the College’s prime urban tury. -

An Improbable Venture

AN IMPROBABLE VENTURE A HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO NANCY SCOTT ANDERSON THE UCSD PRESS LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California and Nancy Scott Anderson All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anderson, Nancy Scott. An improbable venture: a history of the University of California, San Diego/ Nancy Scott Anderson 302 p. (not including index) Includes bibliographical references (p. 263-302) and index 1. University of California, San Diego—History. 2. Universities and colleges—California—San Diego. I. University of California, San Diego LD781.S2A65 1993 93-61345 Text typeset in 10/14 pt. Goudy by Prepress Services, University of California, San Diego. Printed and bound by Graphics and Reproduction Services, University of California, San Diego. Cover designed by the Publications Office of University Communications, University of California, San Diego. CONTENTS Foreword.................................................................................................................i Preface.........................................................................................................................v Introduction: The Model and Its Mechanism ............................................................... 1 Chapter One: Ocean Origins ...................................................................................... 15 Chapter Two: A Cathedral on a Bluff ......................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

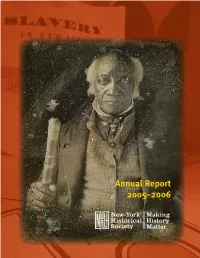

Annual Report 2005°2006

"OOVBM3FQPSU ° #PBSEPG5SVTUFFT Roger Hertog, Chair 4FOJPS4UBGG Richard Gilder, Co-Chair, Louise Mirrer Laura Smith Executive Committee President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President for Institutional Nancy Newcomb, Co-Chair, Stephanie Benjamin Advancement and Strategic Initiatives Executive Committee Executive Vice President and Janine Jaquet Chief Operating Officer Vice President for Development and Louise Mirrer, President and CEO Linda S. Ferber Executive Director of the Chairman’s Vice President and Council William Beekman Director of the Museum Andrew Buonpastore Judith Roth Berkowitz Jean W. Ashton Vice President for Operations David Blight Vice President and Director Richard Shein Ric Burns of the Library Chief Financial Officer James Chanos Laura Washington Roy Eddey Craig Cogut Vice President for Communications Director of Museum Administration Elizabeth B. Dater Barbara Knowles Debs 8MJJER]7XYHMSW8VYQTIX'VIITIVWLEHISRQSWEMG 'SZIV9RMHIRXMJMIHTLSXSKVETLIV'EIWEV%7PEZI Joseph A. DiMenna FEWIG+MJXSJ(V)KSR2IYWXEHX (EKYIVVISX]TI'SPPIGXMSRSJXLI2I[=SVO Charles E. Dorkey, III 2 ,MWXSVMGEP7SGMIX]0MFVEV] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Richard Gelfond Kenneth T. Jackson Joan C. Jakobson David R. Jones Patricia Klingenstein Sidney Lapidus Lewis E. Lehrman Alan Levenstein Glen S. Lewy Tarky Lombardi, Jr. Sarah E. Nash Russell Pennoyer Charles M. Royce Thomas A. Saunders, III Pam B. Schafler Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. Bernard Schwartz Emanuel Stern Ernest Tollerson Sue Ann Weinberg Byron R. Wien Hope Brock Winthrop )POPSBSZ5SVTUFFT Patricia Altschul Leila Hadley Luce 'SPNUIF$P$IBJST Christine Quinn and Betsy Gotbaum, undisputed “first ladies” of New York City government, at our Strawberry Luncheon this year. Lynn Sherr, award-winning correspondent for ABC’s 20/20, spoke eloquently on the origins and significance of the song America the Beautiful and the backgrounds of its authors. -

Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8057gjv No online items Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Clay Stalls William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University One LMU Drive, MS 8200 Los Angeles, CA 90045-8200 Phone: (310) 338-5710 Fax: (310) 338-5895 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.lmu.edu/ © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Charles Luckman Papers, CSLA-34 1 1908-2000 Charles Luckman Papers, 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 William H. Hannon Library Loyola Marymount University Los Angeles, California Processed by: Clay Stalls Date Completed: 2008 Encoded by: Clay Stalls © 2012 Loyola Marymount University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charles Luckman papers Dates: 1908-2000 Collection number: CSLA-34 Creator: Luckman, Charles Collection Size: 101 archival document boxes; 16 oversize boxes; 2 unboxed scrapbooks, 2 flat files Repository: Loyola Marymount University. Library. Department of Archives and Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90045-2659 Abstract: This collection consists of the personal papers of the architect and business leader Charles Luckman (1909-1999). Luckman was president of Pepsodent and Lever Brothers in the 1940s. In the 1950s, with William Pereira, he resumed his architectural career. Luckman eventually developed his own nationally-known firm, responsible for such buildings as the Boston Prudential Center, the Fabulous Forum in Los Angeles, and New York's Madison Square Garden. Languages: Languages represented in the collection: English Access Collection is open to research under the terms of use of the Department of Archives and Special Collections, Loyola Marymount University. Publication Rights Materials in the Department of Archives and Special Collections may be subject to copyright. -

Cosimo I De' Medici As Collector

The Reception of Chinese Art across Cultures Edited by Michelle Ying-Ling Huang TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations …………………………………………………....................... x Introduction by Michelle Ying-Ling Huang …………………………................... ? Chapter Abstracts ………………………………………………………………… ? Part I: Blending Chinese and Foreign Cultures Chapter One ………………………………………………………………............ 2 Shades of Mokkei: Muqi-Style Ink Painting in Medieval Kamakura Aaron M. Rio Chapter Two ……………………………………………………………….......... 23 Mistakes or Marketing? Western Responses to the Hybrid Style of Chinese Export Painting Maria Kar-Wing Mok Chapter Three ………………………………………………………………........ 45 “Painted Paper or Pekin”: The Taste for Eighteenth-Century Chinese Papers in Britain, c. 1918-c. 1945 Clare Taylor Chapter Four ……………………………………………………………….......... 66 “Chinese Painting” by Zdeněk Sklenář Lucie Olivová Part II: Envisioning Chinese Landscape Art Chapter Five ……………………………………………………………….......... 88 Binyon and Nash: British Modernists’ Conception of Chinese Landscape Painting Michelle Ying-Ling Huang Chapter Six ……………………………………………………………….......... 115 In Search of Paradise Lost: Osvald Sirén’s Scholarship on Garden Art Minna Törmä viii Table of Contents Chapter Seven ………………………………………………………………..... 130 The Return of the Silent Traveller Mark Haywood Part III: Conceptualising Chinese Art through Display Chapter Eight ………………………………………………………………...... 154 Aesthetics and Exclusion: Chinese Objects in Nineteenth-Century American Visual Culture Lenore Metrick-Chen Chapter Nine ………………………………………………………………...... -

Postercollectioninventory2.Pdf

CIA ARCHIVES -- POSTER COLLECTION p.1 Last updated 3/2015 Revised lists are posted only when there are significant revisions; you may wish to check with the library staff for the most up-to-date information. COLLECTION SCOPE The Institute Archives collection of CIA posters is incomplete, and most posters date from the 1960s. Flat posters are stored in the flat file, while posters in folded format are usually kept in the publications file. There is duplication between these two collections. This collection contains a new large format items that are not strictly posters. Student Independent Exhibition (S.I.E.) posters and collateral materials have been digitized and are available on Flickr as well as the Institute’s local digital image collection (ARTstor Shared shelf). For help viewing either of these digital archives, please contact the library staff. NOTES: The designation ND means “no date” indicating that there was no year printed on the item, and the library staff was unable to determine the publication year. An index of each drawer and folder is available on the following pages. * * * COLLECTION ACCESS To see a poster, please contact the library staff at least two business days in advance. The staff is not able to pull posters without prior arrangement. All posters must be viewed in the library. * * * SHELVING Unfolded posters are stored in acid free folders in the gray flat file in the store room; for the folded posters in the publications file, SEE ALSO the publications file index. CIA ARCHIVES -- POSTER COLLECTION p.2 Drawer # -

Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri

NYU Urban Design and Architecture Studies New York Area Calendar of Events October 2019 Happy Archtober! Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 Workplace Mid-Century NYBG Edible Richmond Hill Wednesday: Modern Academy Tour North Tour Deborah Berke Architecture Partners Travel Guide Architecture Church of the Power Hour: Transfiguration New Tools: Urban Design Exploring the Revolutionizing Innovation Washington Garden Design the Design within Air Square Walk: The Process Quality and Neighborhood Flower Garden Urban Heat at Wave Hill Brooklyn Island Effect Paul Rudolph Children’s Heritage Museum Tour Architecture of Foundation Nature/Nature Open House of Architecture Paola Antonelli: Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 The Secrets of The Vilcek Building 77 Pratt Student Women in Atelier Louis Kahn’s the Brooklyn Foundation Tour Union Tour Sustainability & Bow-Wow & Modernism & Bridge Tour Energy Tackles Rirkrit the Architecture Behind the the Climate Tiravanija Architecture of Prospect Park The BQE in and the Lights Scenes at the Mobilization Memorializatio Tour: Hidden Context: of Gotham: Practice for Act Prospect Park n Treasures Communities, Nighttime Boat Architecture Tour Infrastructure, Tour and Urbanism Rahul Mehrotra A Monument to Fort and Public (PAU) and Filiep Digital Memory: Wadsworth Space Decorte Urbanisms Fraunces Tour Lecture Conference Tavern RCR Nature into Art: Arquitectes: City College of SCALEX Architecture The Gardens Timeless New York Professional Power Hour: of Wave Hill- A Graduate Seminar Exploring the Moderate Landscape School Open Washington Conversation Design House Square Lecture: The Neighborhood Animated Prospect 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Empire Eleena Jamil Collecting Ennead Murray Moss Open House Open House Landing Architect Design with Dr. -

Surface, Model, & Text THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

American Electric Power: Surface, Model, & Text THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Art in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David Samuel van Strien Graduate Program in Art The Ohio State University 2017 Thesis Committee: George Rush, Advisor Laura Lisbon Michael Mercil Copyright by David Samuel van Strien 2017 Abstract This thesis examines my work. I am interested in how we encounter and experience architectural representations. I will address how my work explores this through the typology of corporate modernist architecture as represented by the American Electric Power (AEP) building in Columbus, Ohio. I make several types of work including rubbings, laser etchings of photographs of models, text pieces, graphite drawings, and digital 3-D models. In this thesis I will analyse these practices, focusing on the rubbings, laser etchings and text pieces. I am especially interested in exploring how we see, experience and interpret architecture, and how the work complicates this relationship for the viewer. I will describe how and why I have researched and accessed the building, the kinds of work this has produced, and the implications that these different forms of architectural representations possibly might have. I am driven by the question of how I can challenge and reject the notion that there is a singular or correct way of reading architecture. At its core, my project is about how and where architecture, and its experiences, exist. A large part of my practice has been research based, in the form of archival visits and readings. -

A Finding Aid to the Viktor Schreckengost Papers, 1933-1995, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Viktor Schreckengost Papers, 1933-1995, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson 2018/10/05 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Viktor Schreckengost papers, 1933-1995................................................. 4 Viktor Schreckengost papers AAA.schrvikt Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Viktor Schreckengost papers Identifier: AAA.schrvikt Date: 1933-1995 Creator: Schreckengost, Viktor, 1906- Extent: 0.7 Linear feet Language: English . Summary: The scattered