Cleveland Art School Exhibit Notes Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edwin Kaufman

A PUBLICATION OF THE COLLECTIVE ARTS NETWORK | CLEVELAND ART IN NORTHEAST OHIO | WINTER 2013/2014 A LIFE CUT SHORT: EDWIN KAUFMAN | ANNUS MIRABILIS: FRANK ORITI| PRODUCTION REPRODUCTION | ARTSCAPE: CRISTY GRAY Cleveland Institute of Art Student Independent Exhibition Feb 14–Mar 15, 2014 cia.edu/sie2014 THANKOn the third Friday in November, galleries YOU of 78th Street Studios offered a spate of noteworthy shows and at- tracted huge crowds. The retrospective of works by the late Randall Tiedman, presented cooperatively by Hilary Gent's Hedge Gallery and William Scheele's Kokoon Arts Gallery, continued to amaze with its moods and diversity. Down the hall and around the corner, Kenneth Paul Lesko Galleries offered new works by Judith Bran- community ı hone your craft ı build your business don, who is working her stormy weather magic larger space ı employment ı money ı insurance than ever. Downstairs, figure drawings by Derek Hess captivated with their emotion and agitated lines while the artist signed books for a long line of fans. Upstairs at Survival Kit, the string quartet Opus 216 and vocal ensemble {re:voice} held rapt a wall-to-wall crowd with the minimalist, morphing sounds of Philip Glass to mark the closing of the exhibit, Human Imprints. Just about every room had people marveling at the art scene in Cleveland: local artists and performers were presenting great work, drawing crowds, building the audience, and making sales. Perhaps we were even surprising ourselves. And in just about every room, someone told me they had taken CAN Journal to another city and showed this magazine to other people in other galleries, with con- GOT SPACE? Go to myCreativeCompass.org sistent amazement: This much art? This many venues? This magazine? This is Cleveland? A tool to directly connect Cleveland-area artists CAN Journal could not be more pleased to be car- 2 with available space and opportunity to grow ried around the country by artists, to play the role of an even stronger region. -

The Sculpture Center 1834 East 123Rd Street Cleveland, Ohio 44106-1910

THE SCULPTURE CENTER 1834 EAST 123RD STREET CLEVELAND, OHIO 44106-1910 November 15, 2004 Contact: Deirdre Lauer, Director of Exhibitions & Public Programs 216-229-6527 Significant Sculpture Presented in Private Collections Exhibition The Sculpture Center presents Private Collections, December 17, 2004 – January 21, 2005, a rare opportunity to view an exciting display of impressive sculpture culled from Cleveland’s most significant private collections, that includes works by internationally recognized sculptors, members of The Cleveland School and significant local artists. Many of these works have never been publicly exhibited before. The Sculpture Center, best known for its exhibitions of emerging artists, offers Private Collections to place the work of emerging artists in context with an informed look at what are considered more traditional forms. Private Collections will prompt discussion of what makes a lasting artistic impression and what led certain artists to success in their careers. Generous private collectors have loaned two- and three-dimensional works by sculptors with international reputations such as Isamu Noguchi, Claes Oldenburg, Arnaldo Pomodoro and Mark di Suvero, among others, as well as pieces by venerated Cleveland artists such as Viktor Schreckengost, William McVey, Edris Eckhardt and David E. Davis. Collectors have also loaned valuable works by local artists David Deming, Robert Thurmer, Terry Durst, Bruce Biro and Andrew Chakalis. The exhibition will open December 17, 2004 and run through January 21, 2005. The opening night reception will take place December 17 from 5:30 pm – 8:30 pm and will feature a gallery talk by the curator, noted art historian Professor Edward J. Olszewski. The cost for this special reception is $15 per person or $25 per couple. -

1272 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board

1272 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting November 20, 2014 Trustees Room Louis Stokes Wing 12:00 Noon Present: Mr. Seifullah, Ms. Rodriguez, Mr. Corrigan, Mr. Hairston, Mr. Werner Absent: Ms. Butts, Mr. Parker Ms. Rodriguez called the meeting to order at 12:10 p.m. MINUTES OF REGULAR BOARD MEETING OF Approval of the Minutes 10/16/14; JOINT FINANCE & HUMAN Mr. Hairston moved approval of the minutes for the RESOURCES 10/16/14 Regular Board Meeting; 10/14/14 Joint Finance & COMMITTEE Human Resources Committee Meeting. Ms. Rodriguez MEETING OF seconded the motion, which passed unanimously by roll 10/14/14 call vote. Approved Presentation: An Introduction to the Friends' Planned Advocacy Program Jason Jaffery, Executive Director, Friends of the Cleveland Public Library, stated that the Friends plan for expansion focused on the following areas: (1) Increased Philanthropy; (2) Increased visibility and volunteer opportunities; and (3) Advocacy on behalf of Cleveland Public Library. Mr. Jaffery stated that ultimately, all high-impact organizations bridge the divide between service and advocacy . They become good at both. And the more they serve and advocate, the more they achieve impact. The Friends growth strategy is based on Friends of St. Paul Model. Advocacy is key to their success Last year, they raised three times as much for their library through advocacy efforts as they did through philanthropy. Advocacy became a top priority. There is an opportunity to restore the Public Library Fund that could result in a potential 7 figure impact on the library's budget. 1273 A key success of this initiative is a new staff position: Director Of Programs & Advocacy to play a leadership role in the Restore the PLF campaign and to build an ongoing program to support the library's relationships with public officials. -

Annual Report 2005°2006

"OOVBM3FQPSU ° #PBSEPG5SVTUFFT Roger Hertog, Chair 4FOJPS4UBGG Richard Gilder, Co-Chair, Louise Mirrer Laura Smith Executive Committee President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President for Institutional Nancy Newcomb, Co-Chair, Stephanie Benjamin Advancement and Strategic Initiatives Executive Committee Executive Vice President and Janine Jaquet Chief Operating Officer Vice President for Development and Louise Mirrer, President and CEO Linda S. Ferber Executive Director of the Chairman’s Vice President and Council William Beekman Director of the Museum Andrew Buonpastore Judith Roth Berkowitz Jean W. Ashton Vice President for Operations David Blight Vice President and Director Richard Shein Ric Burns of the Library Chief Financial Officer James Chanos Laura Washington Roy Eddey Craig Cogut Vice President for Communications Director of Museum Administration Elizabeth B. Dater Barbara Knowles Debs 8MJJER]7XYHMSW8VYQTIX'VIITIVWLEHISRQSWEMG 'SZIV9RMHIRXMJMIHTLSXSKVETLIV'EIWEV%7PEZI Joseph A. DiMenna FEWIG+MJXSJ(V)KSR2IYWXEHX (EKYIVVISX]TI'SPPIGXMSRSJXLI2I[=SVO Charles E. Dorkey, III 2 ,MWXSVMGEP7SGMIX]0MFVEV] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Richard Gelfond Kenneth T. Jackson Joan C. Jakobson David R. Jones Patricia Klingenstein Sidney Lapidus Lewis E. Lehrman Alan Levenstein Glen S. Lewy Tarky Lombardi, Jr. Sarah E. Nash Russell Pennoyer Charles M. Royce Thomas A. Saunders, III Pam B. Schafler Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. Bernard Schwartz Emanuel Stern Ernest Tollerson Sue Ann Weinberg Byron R. Wien Hope Brock Winthrop )POPSBSZ5SVTUFFT Patricia Altschul Leila Hadley Luce 'SPNUIF$P$IBJST Christine Quinn and Betsy Gotbaum, undisputed “first ladies” of New York City government, at our Strawberry Luncheon this year. Lynn Sherr, award-winning correspondent for ABC’s 20/20, spoke eloquently on the origins and significance of the song America the Beautiful and the backgrounds of its authors. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

DIRECTOR's REPORT November 20, 2014 Fighting Community

DIRECTOR’S REPORT November 20, 2014 Fighting Community Deficits During the month of October the Library hosted a total of 184 programs. Educational programming and services, not included in the above totals, accounted for approximately 121 adult education classes, and 663 hours of after-school homework help for grades K-8. After-school snacks were served M-Th. at 18 branch locations. Impact 216, the program formerly known as Rocking the 216, held 88 ACT sessions at 4 CPL locations: Eastman, South Brooklyn, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Harvard- Lee. Business Chinese classes continued at Main library and occurred on 8 occasions with an average class size of 23 adult students. Legal Aid @ YourLibrary On Saturday, October 18 the Lorain Branch hosted the Legal Aid @ Your Library clinic. Thirty-three families signed up to receive a free consultation from a volunteer attorney. Student volunteers from four law schools: Case Western University, Carnegie Mellon, Akron University, and Harvard were on hand to conduct intake interviews. Legal Aid had two volunteers providing foreign language interpretation (Spanish, Burmese) serving at least four patron groups. Thirteen lawyers from Jones Day, including the former President of the local Bar Association, met with met with the families over the course of the morning and into the early afternoon. On October 14 the Library partnered with The Foundation Center to present Rising Tide: The Empowerment of Low-Income Women. Rising Tide is a series of multimedia gatherings created to demonstrate how philanthropy accelerates social change and showcases new ways of solving old problems by lifting up social innovators who are changing our region. -

Postercollectioninventory2.Pdf

CIA ARCHIVES -- POSTER COLLECTION p.1 Last updated 3/2015 Revised lists are posted only when there are significant revisions; you may wish to check with the library staff for the most up-to-date information. COLLECTION SCOPE The Institute Archives collection of CIA posters is incomplete, and most posters date from the 1960s. Flat posters are stored in the flat file, while posters in folded format are usually kept in the publications file. There is duplication between these two collections. This collection contains a new large format items that are not strictly posters. Student Independent Exhibition (S.I.E.) posters and collateral materials have been digitized and are available on Flickr as well as the Institute’s local digital image collection (ARTstor Shared shelf). For help viewing either of these digital archives, please contact the library staff. NOTES: The designation ND means “no date” indicating that there was no year printed on the item, and the library staff was unable to determine the publication year. An index of each drawer and folder is available on the following pages. * * * COLLECTION ACCESS To see a poster, please contact the library staff at least two business days in advance. The staff is not able to pull posters without prior arrangement. All posters must be viewed in the library. * * * SHELVING Unfolded posters are stored in acid free folders in the gray flat file in the store room; for the folded posters in the publications file, SEE ALSO the publications file index. CIA ARCHIVES -- POSTER COLLECTION p.2 Drawer # -

A Finding Aid to the Viktor Schreckengost Papers, 1933-1995, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Viktor Schreckengost Papers, 1933-1995, in the Archives of American Art Jayna M. Josefson 2018/10/05 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Viktor Schreckengost papers, 1933-1995................................................. 4 Viktor Schreckengost papers AAA.schrvikt Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Viktor Schreckengost papers Identifier: AAA.schrvikt Date: 1933-1995 Creator: Schreckengost, Viktor, 1906- Extent: 0.7 Linear feet Language: English . Summary: The scattered -

2006/2007 Annual Report in Celebration of the 70Th Anniversary of the Museum

2006 / 2007 Annual Report Celebrating the Past, Envisioning the Future Mission Statement The Mint Museum is a unique gathering place for people to experience art [OYV\NOZPNUPÄJHU[HUK]HYPLKJVSSLJ[PVUZLUNHNPUNL_OPIP[PVUZHUKPUUV]H[P]L LK\JH[PVUHSWYVNYHTZ Artistic Vision At The Mint Museum, we believe that art creates a unique experience which can positively transform peoples’ lives and that this experience must be physically and intellectually accessible to our entire community. Our passion for art is conveyed through stimulating scholarship, creative presentation, innovative educational programs and our collection. ;OL4PU[4\ZL\TJVSSLJ[Z^VYRZVM[OLOPNOLZ[X\HSP[`HUKTLYP[YLÅLJ[PUN[OLKP]LYZP[`VM artistic endeavor. We will celebrate and augment the display of our permanent collection with ZPNUPÄJHU[[YH]LSPUNL_OPIP[PVUZHUKJVSSHIVYH[PVUZ^P[OV[OLYPUZ[P[\[PVUZ>L^PSSLUOHUJL our strengths in Ceramics, Historic Costume and Art of the Ancient Americas to demonstrate our leadership in these areas. We will aggressively build important collections of American Art, Contemporary Art and Contemporary Craft. Through these efforts, we will tell the story of humanity’s collective artistic aspirations to our local, regional and national audiences. We recognize that the ownership of artworks is an obligation; one of stewardship for future generations. We acknowledge our responsibility to contribute dialogue through research, publications and exhibitions to continue our role as leaders in the visual arts. At The Mint Museum, we are committed to using our talents and resources to inspire our public’s curiosity and to nurture their aesthetic appreciation and critical awareness. Artistic Focus The Mint Museum’s artistic focus is American Art, Art of the Ancient Americas, Ceramics, Contemporary Art, Contemporary Craft and Historic Costume. -

CAN Journal Summer 2015-2

A PUBLICATION OF THE COLLECTIVE ARTS NETWORK | CLEVELAND ART IN NORTHEAST OHIO | SUMMER 2015 A SLICE OF A TREE | WOOD ENGRAVERS NATIONAL CONFERENCE | CLEVELAND NEIGHBORHOODS | SUMMER FESTIVAL GUIDE Cleveland Institute of Art Creativity Matters Consolidated Ad 2 1 Coming this August The Cleveland Institute of Art, and its public programs, have a brand new home. New Peter B. Lewis Theater for the Cinematheque New Reinberger Gallery for exhibitions New facilities for youth + adult continuing education classes The Cleveland Institute of Art is supported in part by the residents of Cuyahoga County through a public grant from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture. Cleveland Institute of Art cia.edu summer 2015 THANKAt any given time the Collective Arts YOUNetwork is a shared labor proposition: our efforts depend on a lot of people pitching in. In the Spring of 2015, we had an unusually large number of projects all happening at once. For any of them to succeed has required a lot of people to go above and beyond the usual call of this collaboration. For people reading this the night of our So You Think BECAUSE CLEVELAND HAS MOMENTUM You CAN Sing karaoke benefit, the first thing that comes to mind is the long list of volunteers who helped make our When people ask whether CAN benefits from No one reading this will be surprised to read that CAN benefit a success. The committee included Karen Petkovic Cuyahoga County’s cigarette tax, what they want to wants you to vote in favor when the renewal of the levy (BAYarts), Hilary Gent (HEDGE Gallery), Nancy Heaton know is whether Collective Arts Network receives an is on the ballot in November. -

1185 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board

1185 CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY Minutes of the Regular Board Meeting December 19, 2013 Trustees Room Louis Stokes Wing 12:00 Noon Present: Mr. Corrigan, Ms. Rodriguez, Mr. Seifullah, Mr. Parker, Mr. Hairston (arrived, 12:24 p.m.), Mr. Werner (arrived, 12:27 p.m.) Absent: Ms. Butts Mr. Corrigan called the meeting to order at 12:13 p.m. Approval of the Minutes MINUTES OF REGULAR BOARD Mr. Seifullah moved approval of the minutes for the MEETING OF 11/21/13 Regular Board Meeting; and the 11/19/13 Finance 11/21/13; FINANCE Committee Meeting. Mr. Parker seconded the motion, COMMITTEE which passed unanimously by roll call vote. MEETING OF 11/19/13 Presentation: Anne Marie Warren, Friends of the Approved Cleveland Public Library Before introducing Anne Marie Warren, Executive Director, Friends of the Cleveland Public Library, Mr. Corrigan stated that he recently attended the Friends Annual Meeting where he and Director Thomas became Ex- Offico board members. Ms. Warren congratulated the Library on the success of the passage of the levy and stated that the Friends was proud to be a partner in that major initiative. Ms. Warren acknowledged that in their 50 year history, the Friends provided $1,000,000 in financial support to the Library and look forward to continuing that support annually. Ms. Warren introduced the following new members of the Friends of the Cleveland Public Library: Aaron O’Brien, Baker & Hostetler LLP and John Siemborski, Ernst & Young. Mr. Corrigan thanked Ms. Warren for her presentation and expressed appreciation to the Friends for their partnership and support. -

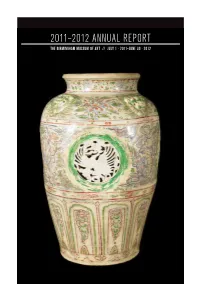

2011–2012 Annual Report

2011–2012 ANNUAL REPORT THE BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM OF ART // JULY 1 · 2011–JUNE 30 · 2012 2011–2012 ANNUAL REPORT THE BIRMINGHAM MUSEUM OF ART // JULY 1 · 2011–JUNE 30 · 2012 CONTENTS THE YEAR IN REVIEW 5 EXHIBITIONS 9 Ralph D. Cook – Chairman of the Board EDUCATION AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS 17 Gail C. Andrews – The R. Hugh Daniel Director EVENTS 25 Editor – Rebecca Dobrinski Design – James Williams SUPPORT GROUPS 31 Photographer – Sean Pathasema STAFF 36 MISSION To provide an unparalleled cultural and educational experience to a diverse community by collecting, presenting, interpreting, and preserving works of art of the highest quality. FINANCIAL REPORT 39 Birmingham Museum of Art ACQUISITIONS 43 2000 Rev. Abraham Woods Jr. Blvd. Birmingham, AL 35203 COLLECTION LOANS 52 Phone: 205.254.2565 www.artsbma.org BOARD OF TRUSTEES 54 [COVER] Jar, 16th century, Collection of the Art Fund, Inc. at the Birmingham Museum of Art; Purchase with funds provided by the Estate of William M. Spencer III AFI289.2010 MEMBERSHIP AND SUPPORT 57 THE YEAR IN REVIEW t is a pleasure to share highlights from our immeasurably by the remarkable bequest of I 2011–12 fiscal year. First, we are delighted long-time trustee, William M. Spencer III. Our to announce that the Museum’s overall collection, along with those at the MFA Boston attendance last year jumped by an astonishing and Metropolitan Museum of Art, is ranked as 24 percent. While attendance is only one metric one of the top three collections of Vietnamese by which we gauge interest and enthusiasm Ceramics in North America. The show and for our programs, it is extremely validating catalogue, published by the University of as we continue to grow and explore new ways Washington Press, received generous national to engage our audience.