The Second Missionary Journey” © All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

Chapter One Phonetic Change

CHAPTERONE PHONETICCHANGE The investigation of the nature and the types of changes that affect the sounds of a language is the most highly developed area of the study of language change. The term sound change is used to refer, in the broadest sense, to alterations in the phonetic shape of segments and suprasegmental features that result from the operation of phonological process es. The pho- netic makeup of given morphemes or words or sets of morphemes or words also may undergo change as a by-product of alterations in the grammatical patterns of a language. Sound change is used generally to refer only to those phonetic changes that affect all occurrences of a given sound or class of sounds (like the class of voiceless stops) under specifiable phonetic conditions . It is important to distinguish between the use of the term sound change as it refers tophonetic process es in a historical context , on the one hand, and as it refers to phonetic corre- spondences on the other. By phonetic process es we refer to the replacement of a sound or a sequenceof sounds presenting some articulatory difficulty by another sound or sequence lacking that difficulty . A phonetic correspondence can be said to exist between a sound at one point in the history of a language and the sound that is its direct descendent at any subsequent point in the history of that language. A phonetic correspondence often reflects the results of several phonetic process es that have affected a segment serially . Although phonetic process es are synchronic phenomena, they often have diachronic consequences. -

Corinth in the First Century Ad: the Search for Another Class

Tyndale Bulletin 52.1 (2001) 139-148. CORINTH IN THE FIRST CENTURY AD: THE SEARCH FOR ANOTHER CLASS Dirk Jongkind Summary A consideration of living spaces in ancient Corinth suggests that it is not possible to characterise its society as one made up merely of a very small number of élite alongside vast numbers of non-élite who were extremely poor. The variety of housing suggests the existence of another class. Introduction The city of Corinth had a glorious Hellenic past before its destruction by the Romans in 146 BC. Yet when it was refounded in 44 BC, it was not rebuilt as a Greek city, but as a Roman colony. Due to its economically strategic position near the Isthmus, the city prospered under Roman emperors. The apostle Paul wrote letters to the church of this city. According to some scholars (Theissen, Judge, Meeks), class-distinctions and social tensions within the church played a major role in the background against which Paul wrote. Though it is admitted that the Corinthians, like others, had ‘the poor always with them’, it is also argued from primary evidence that a portion of the Corinthian church belonged to the upper class. This view has recently received heavy criticism from Justin Meggitt, who in his comprehensive and lucid study Paul, Poverty, and Survival divides Roman society into essentially two groups: the élite and non-élite. The latter led a life just above starvation level: ‘In their experience of housing, as well as in their access to food and clothing, the Greco-Roman non-élite suffered a subsistence or near subsistence life.’1 According to Meggitt, this non-élite group 1 Justin J. -

Performing Death in Tyre: the Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria

University of Groningen Performing Death in Tyre de Jong, Lidewijde Published in: American Journal of Archaeology DOI: 10.3764/aja.114.4.597 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): de Jong, L. (2010). Performing Death in Tyre: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria. American Journal of Archaeology, 114(4), 597-630. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.4.597 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Barnabas, His Gospel, and Its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri

Reflections Reflections Barnabas, His Gospel, and its Credibility Abdus Sattar Ghauri The name of Joseph Barnabas has never been strange or unknown to the scholars of the New Testament of the Bible; but his Gospel was scarcely known before the publication of the English Translation of ‘The Koran’ by George Sale, who introduced this ‘Gospel’ in the ‘Preliminary Discourse’ to his translation. Even then it remained beyond the access of Muslim Scholars owing to its non-availability in some language familiar to them. It was only after the publication of the English translation of the Gospel of Barnabas by Lonsdale and Laura Ragg from the Clarendon Press, Oxford in 1907, that some Muslim scholars could get an approach to it. Since then it has emerged as a matter of dispute, rather controversy, among Muslim and Christian scholars. In this article it would be endeavoured to make an objective study of the subject. I. BRIEF LIFE-SKETCH OF BARNABAS Joseph Barnabas was a Jew of the tribe of Levi 1 and of the Island of Cyprus ‘who became one of the earliest Christian disciples at Jerusalem.’ 2 His original name was Joseph and ‘he received from the Apostles the Aramaic surname Barnabas (...). Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius number him among the 72 (?70) disciples 3 mentioned in Luke 10:1. He first appears in Acts 4:36-37 as a fervent and well to do Christian who donated to the Church the proceeds from the sale of his property. 4 Although he was Cypriot by birth, he ‘seems to have been living in Jerusalem.’ 5 In the Christian Diaspora (dispersion) many Hellenists fled from Jerusalem and went to Antioch 6 of Syria. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

THE CHURCHES of GALATIA. PROFESSOR WM RAMSAY's Very

THE CHURCHES OF GALATIA. NOTES ON A REGENT CONTROVERSY. PROFESSOR W. M. RAMSAY'S very interesting and impor tant work on The Church in the Roman Empire has thrown much new light upon the record of St. Paul's missionary journeys in Asia Minor, and has revived a question which of late years had seemingly been set at rest for English students by the late Bishop Lightfoot's Essay on "The Churches of Galatia" in the Introduction to his Commen tary on the Epistle to the Galatians. The question, as there stated (p. 17), is whether the Churches mentioned in Galatians i. 2 are to be placed in "the comparatively small district occupied by the Gauls, Galatia properly so called, or the much larger territory in cluded in the Roman province of that name." Dr. Lightfoot, with admirable fairness, first points out in a very striking passage some of the " considerations in favour of the Roman province." " The term 'Galatia,' " he says, " in that case will comprise not only the towns of Derbe and Lystra, but also, it would seem, !conium and the Pisidian Antioch; and we shall then have in the narrative of St. Luke (Acts xiii. 14-xiv. 24) a full and detailed account of the founding of the Galatian Churches." " It must be confessed, too, that this view has much to recom mend it at first sight. The Apostle's account of his hearty and enthusiastic welcome by the Galatians as an angel of God (iv. 14), would have its counterpart in the impulsive warmth of the barbarians at Lystra, who would have sacri ficed to him, imagining that 'the gods had come down in VOL. -

Kleonai, the Corinth-Argos Road, And

HESPERIA 78 (2OO9) KLEONAI, THE CORINTH- Pages ioj-163 ARGOS ROAD, AND THE "AXIS OF HISTORY" ABSTRACT The ancient roadfrom Corinth to Argos via the Longopotamos passwas one of the most important and longest-used natural routes through the north- eastern Peloponnese. The author proposes to identity the exact route of the road as it passed through Kleonaian territoryby combining the evidence of ancient testimonia, the identification of ancient roadside features, the ac- counts of early travelers,and autopsy.The act of tracing the road serves to emphasizethe prominentposition of the city Kleonaion this interstateroute, which had significant consequences both for its own history and for that of neighboring states. INTRODUCTION Much of the historyof the polis of Kleonaiwas shapedby its location on a numberof majorroutes from the Isthmus and Corinth into the Peloponnese.1The most importantof thesewas a majorartery for north- south travel;from the city of Kleonai,the immediatedestinations of this roadwere Corinthto the north and Argos to the south.It is in connec- tion with its roadsthat Kleonaiis most often mentionedin the ancient sources,and likewise,modern topographical studies of the areahave fo- cusedon definingthe coursesof these routes,particularly that of the main 1. The initial fieldworkfor this Culturefor grantingit. In particular, anonymousreaders and the editors studywas primarilyconducted as I thank prior ephors Elisavet Spathari of Hesperia,were of invaluableassis- part of a one-person surveyof visible and AlexanderMantis for their in- tance. I owe particulargratitude to remainsin Kleonaianterritory under terest in the projectat Kleonai,and Bruce Stiver and John Luchin for their the auspicesof the American School the guardsand residentsof Archaia assistancewith the illustrations. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

An Introduction to the Knowledge of Greek Grammar

AN * INTRODUCTION TO THE KNOWLEDGE or GREEK GRAMMAR. By SAMUEL B. WYLIE, D. D. IN THE WICE PROVOST AND PROFESSOR of ANCIENT LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA. *NWTIET 16). <e) - \ 3} f) iſ a t t I pi} f a, J. whet HAM, 144 CHES NUT STREET. 1838. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1838, by SAMUEL B. Wylie, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. ANDov ER, MAss. Gould & Newman, Printers. **'. … Tº Co PR E FA C E. CoNSIDERING the number of Greek Grammars, already in market, some apology may appear necessary for the introduction of a new one. Without formally making a defence, it may be remarked, that subjects of deep interest, need to be viewed in as many different bearings as can readily be obtained. Grammar, whether considered as a branch of philological science, or a system of rules subservient to accuracy in speaking or writing any language, embraces a most interesting field of research, as wide and unlimited, as the progres sive development of the human mind. A work of such magnitude, requires a great variety of laborers, and even the humblest may be of some service. Even erroneous positions may be turned to good account, should they, by their refutation, contribute to the elucida tion of principle. A desire of obtaining a more compendious and systematic view of grammatical principles, and more adapted to his own taste in order and arrangement, induced the author to undertake, and gov erned him in the compilation of this manual. -

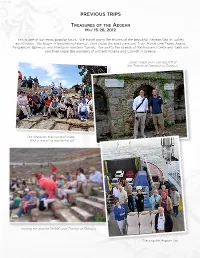

Previous Trips

PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Jacob Shock and Evan Bassett at the Temple of Domitian in Ephesus Our Group on the island of Crete – With a few of us wandering off Visiting the ancient 24,000 seat Theater at Ephesus Crossing the Aegean Sea PREVIOUS TRIPS TREASURES OF THE AEGEAN MAY 15-26, 2012 This is one of our most popular tours. We travel along the shores of the beautiful Aegean Sea in Turkey and Greece. We begin in fascinating Istanbul, then cross the sea to ancient Troy, Alexandria Troas, Assos, Pergamum, Ephesus, and Miletus in western Turkey. We sail to the islands of Patmos and Crete and Santorini and then share the wonders of ancient Athens and Corinth in Greece. Don and grandson Evan at Assos Mars Hill in Athens Well known archaeologist, Cingiz Icten, is pictured with Jacob Shock (left), guide Yeldiz Ergor, and Nancy and Don Bassett at the recently excavated Slope Houses in Ephesus Nancy and her brother Jack Woolf in Istanbul PREVIOUS TRIPS IN THE STEPS OF MOSES AND JOSHUA EGYPT, SINAI, JORDAN, ISRAEL MAY 5-20, 2010 This great tour began with visits to the Giza Pyramids, the Cairo Museum, and the amazing new Library of Alexandria.