Aggressive Driving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safety Tips & More

#thankatrucker T Trusted IN THE R Responsible Safety Zone™ A Awesome Dedicated to Truck Driver Safety Awareness and Wellness JUNE 2020 n VOLUME 13 n ISSUE NO. 3 N Necessary D Dedicated S Safe R Road Warriors Congratulations to Douglas King, F Frontline Heroes I Indispensable TransForce Driver of the Year! O On the Road for Us V Vital n exceptional driver and an employee that all companies would like to have when it comes to R Respected E Efficient “A his work ethics!” Those words were used by our customer, Fourteenth Avenue Cartage to describe Douglas C Conscientious R Reliable King, our Driver of the Year, who we are proud to feature in this issue of In the Safety Zone.™ E Essential S Selfless Winning the Driver of the Year Award here at TransForce is a big deal. Pitted against thousands of drivers, the competition is fierce. Doug has been with TransForce since 2002 and has been working with Fourteenth TransForce Driver Avenue Cartage since 2005. During Referral Program! those years, he has rarely missed a day and has been accident free. What TransForce needs more good drivers a remarkable achievement. When From left to right: David Broome (President and to fill local, regional and OTR openings. asked what his key to success was, CEO, TransForce Group), Paul Braswell (VP, Field he says he just follows the rules, tries Operations and Recruiting), Doug King (Driver of to stay safe and do everything right. the Year), Kimberly Castagnetta (EVP Marketing and Division President Compliance and Safety), We should all follow his lead. -

Illinois Rules of the Road 2021 DSD a 112.35 ROR.Qxp Layout 1 5/5/21 9:45 AM Page 1

DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 1/6/21 10:58 AM Page 1 DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 5/11/21 2:06 PM Page 3 Illinois continues to be a national leader in traffic safety. Over the last decade, traffic fatalities in our state have declined significantly. This is due in large part to innovative efforts to combat drunk and distracted driving, as well as stronger guidelines for new teen drivers. The driving public’s increased awareness and avoidance of hazardous driving behaviors are critical for Illinois to see a further decline in traffic fatalities. Beginning May 3, 2023, the federal government will require your driver’s license or ID card (DL/ID) to be REAL ID compliant for use as identification to board domestic flights. Not every person needs a REAL ID card, which is why we offer you a choice. You decide if you need a REAL ID or standard DL/ID. More information is available on the following pages. The application process for a REAL ID-compliant DL/ID requires enhanced security measures that meet mandated federal guidelines. As a result, you must provide documentation confirming your identity, Social Security number, residency and signature. Please note there is no immediate need to apply for a REAL ID- compliant DL/ID. Current Illinois DL/IDs will be accepted to board domestic flights until May 3, 2023. For more information about the REAL ID program, visit REALID.ilsos.gov or call 833-503-4074. As Secretary of State, I will continue to maintain the highest standards when it comes to traffic safety and public service in Illinois. -

San Diegd Police Department San Diego, California

03-35 SAN DIEGD POLICE DEPARTMENT SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA C/5 C 3 5 Project Summary: Drag-Net San Diego Police Department The Problem: Illegal motor vehicle speed contests, commonly known as street races, throughout the City of San Diego. Analysis: Officers developed a knowledge of the street-racing culture through undercover investigations, interviews with officers who had experience dealing with racers, monitoring Internet websites, interviewing racers, and exploring the legal alternatives that are available. Officers studied data on calls for service, traffic collisions, arrests, and citations related to illegal speed contests. Officers established baseline figures to determine the size of the problem. They identified collateral crimes that were occurring because of the problem. The officers set goals of reducing incidents of street racing to a level that it could be managed with existing resources and to reduce the number of illegally modified vehicles on the roadways. The most important analysis the officers made was whether they could impact the problem, despite its magnitude and history of indifference by society. They realized they had to change society's paradigm about street racing. The Drag-Net Officers decided they would only be successful if they truly made San Diego a safer place. They knew lives could be saved if their analysis was accurate, and the response was effective. Response: Officers used a multi-faceted approach in a comprehensive response strategy: • Undercover operations to identify, apprehend, and prosecute racers -

Frustration, Aggression & Road Rage

Always remember that the primary goal in defensive driving is to stay safe and live to drive another day. Frustration, Aggression The context in which frustration occurs Other road users are probably equally and Road Rage can determine both the nature and extent frustrated in traffic, perhaps more so. of our own resulting aggressive behavior. They may not be as prepared for traffic. There are also differences in people’s nat- Frustration occurs when someone or Be courteous and forgiving. Your ural propensities. Some drivers are something impedes your progress toward behavior may serve to reduce their content to mutter curses to themselves a goal. In the driving environment our goal levels of frustration and consequently while others are provoked to physical is to get to our destination as quickly and their levels of aggression and violence. Both personal attributes and as safely as possible. When other road risk-taking, thereby making the traffic situational factors can moderate our users interfere with our progress we environment safer for everyone, aggressive responses. become frustrated. In the driving environ- including you. ment, increases in aggression can have Some experts distinguish between Do not fret over people, conditions and deadly consequences. Frustration can aggressive driving and road rage. things that you cannot control. Choose lead to any or all of the following Aggressive driving is instrumental, that is, your battles wisely and save your aggressive behaviour: it serves to further progress toward a energy and emotions for situations that desired outcome when we are frustrated. Excessive speeding or street racing you can influence. -

Medication Use and Driving Risks by Tammie Lee Demler, BS Pharm, Pharmd

CONTINUING EDUCATION Medication Use and Driving Risks by Tammie Lee Demler, BS Pharm, PharmD pon successful completion of this ar- the influence of alcohol has Useful Websites ticle, pharmacists should be able to: long been accepted as one 1. Identify the key functional ele- of the most important causes ■ www.dot.gov/ or http://www.dot.gov/ ments that are required to ensure of traffic accidents and driv- odapc/ competent, safe driving. ing fatalities. Driving under Website of the U.S. Department of 2. Identify the side effects associated with pre- the influence of alcohol has Transportation, which contains trends Uscription, over-the-counter and herbal medi- been studied not only in ex- and law updates. It also contains an cations that can pose risks to drivers. perimental research, but also excellent search engine. 3. Describe the potential impact of certain medi- in epidemiological road side ■ www.mayoclinic.com/health/herbal- cation classes on driving competence. studies. The effort that society supplements/SA00044 4. Describe the pharmacist’s duty to warn re- has made to take serious le- Website for the Mayo Clinic, with garding medications that have the potential to gal action against those who information about herbal supplements. impair a patient’s driving competence. choose to drink and drive It offers an expert blog for further exploration about specific therapies and 5. Provide counseling points to support safe driv- has resulted in the significant to receive/share insight about personal ing in all patients who are receiving medication. deterrents of negative social driving impairment with herbal drugs. stigma and incarceration. -

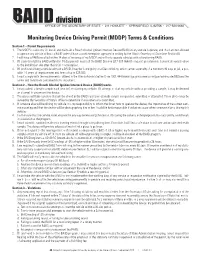

Monitoring Device Driving Permit (MDDP) Terms & Conditions

division OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE • 211 HOWLETT • SPRINGFIELD, IL 62756 • 217-524-0660 Monitoring Device Driving Permit (MDDP) Terms & Conditions Section 1 – Permit Requirements 1. The MDDP is valid only if I install and maintain a Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Device (BAIID) in any vehicle I operate, and that I am not allowed to operate any vehicle without a BAIID unless I have a work exemption approved in writing by the Illinois Secretary of State (see Section 8). 2. I will have a BAIID installed within 14 days of issuance of my MDDP and will only operate vehicles with a functioning BAIID. 3. If I cannot install the BAIID within the 14-day period I must call the BAIID Division (217-524-0660) to request an extension. I am not allowed to drive to the installation site after the initial 14-day period. 4. If I am found driving a vehicle without a BAIID, I may be found guilty of a Class 4 felony, which carries a penalty of a minimum 30 days in jail, a pos- sible 1-3 years of imprisonment and fines of up to $25,000. 5. I must comply with the requirements outlined in the Illinois Administrative Code 1001.444 (www.ilga.gov/commission/jcar/admincode/092) and the Terms and Conditions contained in this document. Section 2 – How the Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Device (BAIID) works 1. I must submit a breath sample each time before starting my vehicle. If I attempt to start my vehicle without providing a sample, it may be deemed an attempt to circumvent the device. -

Road Safety Impact of Ontario Street Racing and Stunt Driving Law

Accident Analysis and Prevention 71 (2014) 72–81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Accident Analysis and Prevention jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aap Road safety impact of Ontario street racing and stunt driving law a a,b,∗ c d Aizhan Meirambayeva , Evelyn Vingilis , A. Ian McLeod , Yoassry Elzohairy , c a c Jinkun Xiao , Guangyong Zou , Yuanhao Lai a Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada b Population and Community Health Unit, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada c Department of Statistical and Actuarial Sciences, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada d Ministry of Transportation of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Objective: The purpose of this study was to conduct a process and outcome evaluation of the deterrent Received 5 December 2013 impact of Ontario’s street racing and stunt driving legislation which came into effect on September 30, Received in revised form 5 May 2014 2007, on collision casualties defined as injuries and fatalities. It was hypothesized that because males, Accepted 13 May 2014 especially young ones, are much more likely to engage in speeding, street racing and stunt driving, the new Available online 2 June 2014 law would have more impact in reducing speeding-related collision casualties in males when compared to females. Keywords: Methods: Interrupted -

Part Three - Traffic Code

PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration, Enforcement and Penalties Chapter 301 Definitions Chapter 303 Enforcement; Impounding Chapter 305 Traffic Control Chapter 307 Traffic Control Map and File Chapter 309 Penalties TITLE THREE - Public Ways and Traffic Control Devices Chapter 311 Obstruction and Special Uses of Public Ways Chapter 313 Traffic Control Devices TITLE FIVE - Vehicles and Operation Chapter 331 Operation Generally Chapter 333 DWI; Reckless Operation; Speed Chapter 335 Licensing; Accidents Chapter 337 Safety and Equipment Chapter 339 Commercial and Heavy Vehicles Chapter 341 Drivers of Commercial Cars or Tractors Chapter 343 [Reserved] Chapter 345 Noise Emission From Motor Vehicles TITLE SEVEN - Parking Chapter 351 Parking Generally Chapter 353 Parking Meters TITLE NINE - Pedestrians, Bicycles, Motorcycles and Snowmobiles Chapter 371 Pedestrians Chapter 373 Bicycles and Motorcycles Chapter 375 Bicycle Licensing (REPEALED 11-22-2010; Ord. 2010-108) Chapter 377 Snowmobiles and All Purpose Vehicles PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration, Enforcement and Penalties Chapter 301 Definitions Chapter 303 Enforcement; Impounding Chapter 305 Traffic Control Chapter 307 Traffic Control Map and File Chapter 309 Penalties CHAPTER 301: DEFINITIONS Section 301.01 Meaning of words and phrases 301.02 Agricultural tractor 301.03 Alley 301.04 Bicycle 301.05 Bus 301.06 Business district; Downtown business district 301.07 Commercial tractor 301.08 Controlled-access highway 301.09 Crosswalk 301.10 Driver or operator 301.11 -

Factors That Impact Driving

LESSON PLAN Factors That Impact Driving NATIONAL HEALTH EDUCATION STANDARDS (NHES) 9-12 Standard 5: Students will analyze the influence of family, peers, culture, media, technology, and other factors on healthy behaviors. • 5.12.2 Determine the value of applying a thoughtful decision-making process in health-related situations. • 5.12.3 Justify when individual or collaborative decision-making is appropriate. • 5.12.4 Generate alternatives to health-related issues or problems. OBJECTIVES Your teen driver education objective is to help students make appropriate driving decisions by first analyzing how various factors impact teen driver safety. Students will achieve this objective by: • Explaining how speed affects teenage driving • Determining the impact of environmental conditions on teenage driving behaviors • Examining the effects of various mental and physical conditions on teenage driving behaviors • Determining the reasons people “take chances” when driving SPEEDING AND DRIVING 1. Have students list different speed limits they encounter while riding or driving in the car. 2. Ask students where they see lower speed limits (residential neighborhoods, etc.) versus where they have seen higher speed limits (highways). 3. Have students discuss the reasons for the variations in speed limits and ask them what might happen if there was just one speed limit, regardless of location. 4. Have students explain the importance of obeying speed limits and the dangers of not obeying speed limits. (cont. on page 2) 1 Do not conduct any activity without adult supervision. This content is provided for informational purposes only. Discovery Education and Toyota assume no liability for your use of the information. Copyright © 2018 Discovery Education. -

Road Rage Factors

ROAD RAGE FACTORS HOW TO AVOID ROAD RAGE Here are some common factors that often Make sure you have the right car insurance policy to contribute to road rage incidents or aggressive protect yourself from aggressive drivers or if you find driving behavior. yourself the victim of a road rage incident. TRAFFIC DELAYS BEFORE YOU GET BEHIND THE WHEEL o Heavy traffic, sitting at stoplights, looking for a o Don’t rush. Give yourself time to get where you’re parking space or even waiting for passengers going; you’re less likely to become impatient and can increase a driver’s anger level. take unnecessary risks. RUNNING LATE o Cool off. If you’re upset, take time to calm down. o Running behind for a meeting or appointment o Be aware and anticipate. If you expect can cause drivers to be impatient. something to happen you can sometimes resolve the issue before it occurs. ANONYMITY o If drivers feel that they probably won’t see WHAT TO REMEMBER WHEN DRIVING other drivers again, they may feel more o Give other drivers a break. If someone is driving comfortable engaging in risky driving slowly, keep in mind they might be lost. behaviors like tailgating, cutting people off, o Use hand gestures wisely. Keep gestures positive - excessive honking or making rude gestures. say, waving to a driver who lets you in when merging. o If the motoring public report these road o Don’t tailgate. Always keep a safe distance from rage incidents to our SEPI office, disciplinary the car in front, no matter how slowly they might measures could be taken with the employee. -

Teen Driving Laws

Info for Parents, Teen Drivers and Their Passengers With tighter restrictions on teen drivers and the • Distracted Driving: It is against the law for Passenger Restrictions For All Learner’s Permit and 16- and need for them and their passengers to be safe, teens to drive distracted as well as use any For the entire time a driver holds a learner’s permit, below are some important reminders for teens, mobile electronic devices while driving. he or she may not have any passengers except 17-Year-Old Licensed Drivers for either: parents, passengers and their communities: • Purposeful Driving: Parents need to • A licensed driving instructor giving instruction They may NOT: continuously monitor and guide their teenagers’ • Transport more passengers than the number driving activity, and limit their travel to and others accompanying that instructor. Managing The Driving Experience • One person who is providing instruction and is of seatbelts in the vehicle. purposeful driving. Once teens begin to engage • Operate any vehicle that requires a public • Crashes Kill Teens: Motor vehicle crashes in joy-riding, their crash-risk increases at least 20 years old, has held a driver’s license are the #1 cause of death for 15-19 year- for four or more consecutive years and whose passenger transportation permit or a vanpool dramatically, and more so with each additional vehicle. old teenagers. teenage passenger. license has not been suspended during the four years prior to training. Parents or legal guardian • Use a cell phone (even if it is hands-free) or • Brain Development: Research shows that the • Health Care Professionals: Pediatricians, family may accompany the instructor. -

Are Youan Aggressive Driver?

Front Panel Back Panel Are YOU an Aggressive Driver? If confronted by an aggressive driver, you should: • Get out of their way as soon as you can safely You are an aggressive driver if you drive in a pushy, bold • Stay calm — reaching your destination safely is your goal or selfish manner, which puts yourself and others at risk. • Do not challenge him or her • Aggressive driving is a contributing factor in nearly half of all • Avoid eye contact crashes in Idaho. • Up to three-fourths of all aggressive-driving crashes occur in • Ignore gestures and don’t return them urban areas. • Always buckle up in case abrupt movements cause you to lose • More than four out of five fatal aggressive-driver crashes that control of your vehicle involved a single vehicle occurred in rural areas. • Young drivers, ages 19 and younger, are over 4 times as likely to be Can I report an Aggressive Driver or Road Rage incident? involved in an aggressive-driving crash than all other drivers. Citizens have the right to report an aggressive-driving or road- rage incident to law enforcement if it is witnessed in the absence of an officer. The following behaviors are considered aggressive driving: The following is the type of information you will need to (Numbers 1-8 are considered traffic violations) provide, if safely possible: 1. Failing to obey traffic-control devices, such as stop/yield/speed 1. Find a safe place to call 911, or call dispatch when you get home. limit signs, traffic signals and roadway markings 2.