Notesontheprogram by James M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Bowden Biography

Mark Bowden Mark Bowden is a British composer of chamber, orchestral and vocal music. His work has been described as ‘an exceptional and absorbing pleasure’ [The Guardian], ‘conjuring up magic and mystery’[Opera], ‘invigorating’ [The Times] and ‘powerfully dramatic’ [BBC Radio 3]. Mark first came to public attention in 2006 when he was awarded the Royal Philharmonic Society Composition Prize for his first orchestral commission, Sudden Light (BBC Symphony Orchestra). Further orchestral commissions followed — The Dawn Halts (BBC National Orchestra of Wales) and Tirlun (Ulster Orchestra) — before being appointed Resident Composer with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, a post he held from 2011 to 2015. Mark’s four-year tenure with the orchestra resulted in a series of major new works, including a cello concerto, Lyra (for Oliver Coates), a dual function percussion concerto & ballet score, Heartland (for National Dance Company Wales) and A Violence of Gifts, a 40-minute cantata for soprano, baritone, chorus and orchestra that premiered in 2015 to widespread critical acclaim with soloists Elizabeth Atherton and Roderick Williams conducted by Martyn Brabbins. Mark’s growing catalogue of chamber music includes The Breaking Wheel for clarinet and piano (Little Missenden Festival), Five Memos for violin and piano (London Music Masters, for Hyeyoon Park & Huw Watkins), Parable for solo saxophone (London Sinfonietta), Lines Written a Few Miles Below for violin and electronics, (Rambert Dance Company, for Thomas Gould), Airs No Oceans Keep (Fidelio Trio), Black Yew, White Cloud (Arditti Quartet) as well as a number of other works for groups with whom he has developed close partnerships, including Chroma, Kokoro, Ostrava Banda, Phiharmonia Orchestra, Spitalfields Festival, London Handel Festival and many others. -

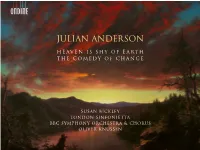

Julian Anderson

JULIAN ANDERSON HEAVEN IS SHY OF EARTH THE COMEDY OF CHANGE SUSAN BICKLEY LONDON SINFONIETTA BBC SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA & CHORUS OLIVER KNUSSEN Julian Anderson JULIAN ANDERSON (b. 1967) The Comedy of Change (2009) 23:48 for chamber ensemble of 12 players 1 I. 2:11 2 II. – 2:47 3 III. 1:55 4 IV. – 2:31 5 V. 3:39 6 VI. 5:30 7 VII. 5:15 Heaven is Shy of Earth (2006/2009–10) 38:32 for mezzo-soprano, chorus & orchestra 8 Intrada 3:10 9 Kyrie 5:07 10 Gloria (with Bird) 6:59 11 Quam dilecta tabernacula tua 5:08 12 Sanctus 8:06 13 Agnus Dei 10:02 London Sinfonietta (1–7) Susan Bickley, mezzo-soprano (9–13) BBC Symphony Chorus (9, 10, 12, 13) BBC Symphony Orchestra (8–13) Oliver Knussen, conductor hen Julian Anderson was commissioned to write a substantial work for solo Wmezzo-soprano, chorus and orchestra for the 2006 BBC Proms, the stage was set for a large-scale summation of his recent musical concerns. Anderson would be able to revisit the communal expressive ideal of several recent works for unaccompanied choir in the context of his by now well-established orchestral style, with its characteristic integration of lyrical simplicity and joyous complexity. The solo female voice, meanwhile, suggested a new and often dramatic presence – an individual consciousness at the heart of one of Anderson’s typical evocations of the natural world. Clearly, the choice of texts would be a central decision. Anderson had set poems by Emily Dickinson before, and now found in her visionary eccentricity a compelling expression of nature’s abundance as a kind of secular miracle. -

Download Booklet

D I F F E R E N T W O R L D Diana Galvydyte Produced and Engineered by Raphaël Mouterde Edited and Mastered by Raphaël Mouterde Recorded on December 19th - 20th Dec 2011 and January 5th - 6th 2012 at The Music Room, Champs Hill, West Sussex, UK Christopher Guild Photographs of Diana and Chris by Benjamin Harte Executive Producer for Champs Hill Records: Alexander Van Ingen VYTAUTAS BARKAUSKAS (b.1931) A DIFFERENT WORLD PARTITA FOR SOLO VIOLIN OP.12 (1967) 1 i Praeludium 0’57 2 ii Scherzo 1’35 The cult of the instrumental virtuoso dates from the early 19th century, when the 3 iii Grave 2’28 burgeoning Romantic movement started to see preternaturally gifted 4 iv Toccata 1’29 instrumentalists as a species of magician, able to conjure music out of the air as if 5 v Postludium 1’40 by magic, and move audiences to extremes of emotion and excitement by the deep EDUARDAS BALSYS (1919-1984) expressivenesss and amazing technical bravura of their playing. The archetypal 6 RAUDA (LAMENT) FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO 3’46 figure who bestowed this image on players of the violin was of course Niccolò 7 DREBULYTÈ IŠDYKÉLÈ (MISCHIEVOUS DREBULYTÈ) FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO 1’55 Paganini, but the tradition of the virtuoso violin showpiece has persisted From the ballet ‘Eglè, Queen of the Serpents (1960) throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. The present recital is devoted JOE SCHITTINO (b.1977) largely to bravura violin works from the mid-20th century onwards, and mostly to 8 POEM ‘EGLÈ’ FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (2011) Premiere recording 10’26 those produced by composers from the Baltic region, alternating and contrasting ESA-PEKKA SALONEN (b.1958) works for unaccompanied violin with those for violin and piano. -

STRAIGHT from the HEART Symphony Hall, Birmingham

STRAIGHT FROM THE HEART Symphony Hall, Birmingham Wednesday 30 June 2021, 2.00pm & 6.30pm Kazuki Yamada – Conductor Alban Gerhardt – Cello Anderson Litanies (CBSO Centenary Commission – UK Premiere) 20’ Dvořák Symphony No.7 40’ Love Dvořák’s New World symphony? Then why not try something a OUR CAMPAIGN FOR MUSICAL little stronger? Dvořák’s Seventh begins with a rumble of thunder, and LIFE IN THE WEST MIDLANDS ends in a shout of defiance; in between come summer storms, lilting dance tunes, and some of the sweetest, most heartfelt music in any These socially-distanced concerts have been made possible by funding from Arts great symphony. The CBSO’s Principal Guest Conductor Kazuki Yamada Council England’s Culture Recovery Fund, never stints on emotion; and it’s a perfectly-chosen complement to the plus generous support from thousands of UK premiere of the CBSO’s latest Centenary Commission – Litanies, individuals, charitable trusts and companies a major new cello concerto from our former Composer in Association through The Sound of the Future fundraising Julian Anderson. It’s Julian’s very personal tribute to a friend who died too campaign. young, and with the phenomenal Alban Gerhardt as soloist, we think it’s set to be an instant classic. By supporting our campaign, you will play your part in helping the orchestra to recover from the pandemic as well as renewing the way we work in our second century. Plus, all new memberships are currently being matched pound for pound by a generous You are welcome to view the online programme on your mobile device, but please ensure that your member of the CBSO’s campaign board. -

Sendak's and Knussen's Intended Audiences of Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop!

CREATIVE DIFFERENCES: SENDAK’S AND KNUSSEN’S INTENDED AUDIENCES OF WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE AND HIGGLETY PIGGLETY POP! by Leah Giselle Field M.Mus., University of Western Ontario, 2008 B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) January 2015 © Leah Giselle Field, 2015 Abstract Author and illustrator Maurice Sendak and composer Oliver Knussen collaborated on two one- act operas based on Sendak’s picture books Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life. Though they are often programmed as children’s operas, Sendak and Knussen labeled the works fantasy operas, but have provided little commentary on any distinction between these labels. Through examination of their notes and commentary on the operas, published reviews and analysis of the operas, e-mail interviews conducted with operatic administrators and composers of children’s operas, and my analysis of the two works I intend to show that Sendak and Knussen had different target audiences in mind as they created these works. ii Preface This dissertation is an original intellectual product of the author, Leah Giselle Field, with the guidance of professors Dr. Alexander J. Fisher and Nancy Hermiston. The e-mail interviews discussed in Chapter II were covered by UBC Behavioral Research Board of Ethics Certificate number H12-03199 under the supervision of Principal Investigator Dr. Alexander J. Fisher. iii Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... -

On the Practice of Repeating Concert Items in Concerts of Modern Or Contemporary Music: Historical Precedents and Recent Contexts

. Volume 14, Issue 2 November 2017 On the practice of repeating concert items in concerts of modern or contemporary music: Historical precedents and recent contexts Julian Anderson, Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London, UK Abstract: This article attempts to draw together a wide range of performing evidence between 1824 and 2005 concerning the repetition of new or unfamiliar music in concert performance. It makes no pretence at being exhaustive, but is a selective history of the phenomenon. Two types of repetition are highlighted: the immediate repetition of a concert item; and the repetition of a concert item on the same concert with other music placed between the two performances. Repetition in successive concerts, and repetition of an item across successive concert seasons, are also examined. The effects of all these practices on concert audiences are documented from available evidence as is, more briefly, the effect of mechanical repetition through the use of audio technology on the audience reception of new music. Certain patterns of audience reaction under all these circumstances are observed. In particular, a strong if not exclusive tendency towards enhanced audience comprehension of new music becomes consistently apparent when a work is repeated, even at the distance of some months. Composers are shown to be both preoccupied with and sensitive to the enhanced reception of their work made possible through repeated performance. Keywords: Audiences; complexity; concerts; density; dissonance; enthusiasm; hostility; perception; reception; repetition Like many composers, concern with audience reception of my music and of modern and contemporary music generally is a persistent if elusive factor of daily working practice. -

Julian Anderson

Update April 2019 Julian Anderson Symphony (2003) drum – harp – electronic keyboard tuned ¼-tone lower – strings Written for the CBSO as part of the composer’s residency with the orchestra orchestra (2001-2005) Duration 18 minutes FP: 1.7.2005, Cheltenham Festival, Cheltenham Town Hall, UK: CBSO/ 3(I=extra fl tuned ¼ tone flat, III=afl+picc).3(III=ca).3(I=extra cl tuned Martyn Brabbins ¼ tone flat, II=cl in A, III=Ebcl+bcl).bcl(=cbcl).3(III=cbsn) – 4.3(III=tpt Score and parts for hire in D).3.1 – timp – perc(4): 4 SD/tam-t/glsp/whip/BD/large tgl/4 susp. cym/tuned c.bells/2 mar/vib/guiro/t.bells/large military drum with snares/2 low tom-t – harp – piano(=keyboard ¼ tone lower) – strings My Beloved Spake (2006) Commissioned by the CBSO SATB chorus & organ FP: 3.12.2003, Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry, UK: CBSO/Sakari Text: from Song of Songs (Eng) Oramo Duration 4½ minutes Score on sale (HPOD1015). FP: 23.9.2006, Chapel, Queen’s College, Oxford, UK: London Score and parts for hire Philharmonic Choir/Neville Creed Score 0-571-52464-8 on sale or available for digital download from Four American Choruses on Gospel Texts (2003) www.fabermusicstore.com SATB a cappella (divisi) (Each of the works can be performed separately or together) Heaven is Shy of Earth (2006) Texts: I’m a Pilgrim – Mary S.B. Dana, Beautiful Valley of Eden – William mezzo-soprano, chorus and orchestra O. Cushin, Bright Morning Star! – Victoria Stuart, At the Fountain – .P. -

Chamber Orchestra

“Anderson really is a composer to cherish” The Times JULIAN ANDERSON List of Works BIOGRAPHY Julian Anderson was born in London in 1967. He started composing at the age of 11, and studied composition with John Lambert in London, CONTENTS Alexander Goehr in Cambridge and Tristan Murail in Paris. He also attended summer courses in composition given by Olivier Messiaen, Biography page 2 Per Nørgård, Oliver Knussen and Gyorgy Ligeti. He won the Royal Philharmonic Society's Young Composer Prize in 1993. From 1997–2000 List of works he was Composer in Residence with Sinfonia 21, and since 2001 he has Orchestral page 3 been Composer-in-Association with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Active as a teacher and writer on music, Anderson has been Chamber Orchestra page 4 Head of Composition at the Royal College of Music, London, since Chamber Ensemble page 4 September 2000 and has published articles on contemporary music Instrumental page 6 internationally. His wide knowledge of contemporary music and his Vocal page 7 presentational skills prompted his appointment, in 2002, as Artistic Choral page 7 Director of the Philharmonia's Music of Today series. Contact details page 8 Anderson's music is characterised by a fresh use of melody, vivid contrasts of texture and lively rhythmic impetus. He has a continuing interest in the music of traditional cultures from outside the Western concert tradition. He has a special love for the folk music of Eastern Europe–especially of the Lithuanian, Polish and Romanian traditions–and has also been much influenced by the modality of Indian ragas. -

Gould Piano Trio

SANIBEL MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAM NOTES GOULD PIANO TRIO Lucy Gould, violin ~ Richard Lester, cello ~ Benjamin Frith, piano with ROBERT PLANE, clarinet Saturday, March 21, 2019 ~ PROGRAM ~ Trio for Clarinet, Cello Johannes BRAHMS And Piano in A minor, Op. 114 (1833-1897) Allegro Adagio Andantino grazioso Allegro Four Fables for Clarinet, Violin, Huw WATKINS Cello, and Piano (b. 1976) Lento Allegro Lento Lento — Andante — Allegro ~ INTERMISSION ~ Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello Antonín DVOŘÁK in F minor, Op. 65 (1841-1904) Allegro ma non troppo Allegretto grazioso Poco adagio Allegro con brio Gould Piano Trio The Gould Piano Trio, which was compared by the Washington Post to the great Beaux Arts Trio for its “musical fire” and “dedication to the genre,” has remained at the forefront of the international chamber music scene for a quarter of a century. Launched by their First Prize at the Melbourne Chamber Music Competition and subsequently selected as “Rising Stars” by Britain’s Young Concert Artists Trust Artists, the ensemble made a highly successful debut at New York’s Weill Recital Hall that was described by Strad Magazine as “Pure Gould.” The Trio’s many appearances at London’s Wigmore Hall have included the complete piano trios of Dvořák, Mendelssohn, and Schubert, plus a Beethoven cycle in 2017-2018 to celebrate the ensemble’s 25th anniversary appearing at that iconic venue. Commissioning and performing new works is an important part of the Gould Trio’s philosophy of remaining creative inspired. Most recently, the Trio premiered Four Fables by Huw Watkins, one of today’s most popular British composers, who was featured at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center this past season. -

Julian Anderson's Symphony

JULIAN ANDERSON’S SYMPHONY: OTHER WORLDS REFLECTED A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Michael John Sherman Small January 2017 © 2017 Michael John Sherman Small JULIAN ANDERSON’S SYMPHONY: OTHER WORLDS REFLECTED Michael John Sherman Small D.M.A. Cornell University 2017 ABSTRACT In recent years, Julian Anderson’s music has been gaining ever-increasing international attention, especially since his residency with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra from 2001 to 2005. Some of Anderson’s most important works were written during this period, including Symphony (2003). Through an examination of the work’s technical construction as well as its connections to seminal works of literature and music, this dissertation gives an account of Symphony as a locus for Anderson’s artistic concerns writ large. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Michael Small was born in Birkenhead, England in 1988. He began his compositional training at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester in 2007, graduating with full honors, and then beginning his DMA at Cornell in August 2011. In 2014, Michael received the Alan Horne prize from the Royal Philharmonic Society as part of their annual Young Composer commissions. His piece for solo violin called White Space written for UK violinist Fenella Humphreys was premiered at the Presteigne Festival in August 2015 and has received performances in Bristol, Oxford, Liverpool, and London, and at the National Galleries of Art in Edinburgh, before a painting by the artist who inspired the work. -

Mcewen Memorial Concert of Scottish Chamber Music

���������������������� Programme cover designed by Katy Cooper McEwen Memorial Concert of Scottish Chamber Music Thursday 8 March 2018 1.10pm University Concert Hall Huw Watkins, piano Robert Schumann Kinderszenen Huw Watkins Sarabande Sally Beamish Night Pieces (World Premiere)* Claude Debussy Preludes (selection from Book I) *Commissioned by the Court of the University of Glasgow under the terms of the McEwen Bequest. Additional funding towards today’s performance has been provided by the Ferguson Bequest. Today’s concert is being recorded. Please remember to switch off all mobile phones. Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Kinderszenen op. 15 (1838) Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood) is a collection of thirteen short pieces. Despite the title being themed around childhood, the collection was created for performance by advanced pianists. Each piece has an evocative title: 1. Von fremden Ländern und Menschen - Of Strange Lands and Peoples 2. Kuriose Geschichte - Curious Story 3. Hasche-Mann - Blind Man’s Bluff 4. Bittendes Kind - Pleading Child 5. Glückes genug - Contented Enough 6. Wichtige Begebenheit - Important Event 7. Träumerei - Reverie 8. Am Kamin - At the Fireside 9. Ritter vom Steckenpferd - Knight of the Hobby Horse 10. Fast zu Ernst - Almost Too Serious 11. Fürchtenmachen - Frightening 12. Kind im Einschlummern - Child Falling Asleep 13. Der Dichter spricht - The Poet Speaks Huw Watkins (b.1976) Sarabande (2014) I wrote my Sarabande for the pianist Piotr Anderszewski in 2014. It's a five minute long piece which explores the characteristic triple time rhythm of this baroque dance form. (Huw Watkins) Sally Beamish (b.1956) Night Dances (2017) There are many reasons why a night might be sleepless. -

SPECTRALISMS 2O19

SpectraliSmS 2019 dition international conference e nd nd 2 edition 2 – Wednesday 12th – Friday 14th June, 2019 S Paris, France m S IRCAM: Salle Stravinsky, Studio 5 Spectrali http://spectralisms2019.ircam.fr Paris, France 14th – Friday 12th Wednesday 2019 June, ORGANISING COMMITTEE ■ Sylvie Benoit (IRCAM) ■ Nicolas Donin (IRCAM, STMS) ■ François-Xavier Féron (CNRS, STMS) ■ Eric de Gélis (IRCAM) ■ Grégoire Lorieux (IRCAM, L’Itinéraire) SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE ■ Jonathan Cross (University of Oxford) ■ Nicolas Donin (IRCAM, STMS) ■ François-Xavier Féron (CNRS, STMS) ■ Joshua Fineberg (Boston University) ■ Robert Hasegawa (McGill University) ■ Gascia Ouzounian (University of Oxford) ■ Ingrid Pustijanac (University of Pavia) ■ Caroline Rae (Cardiff University) Organised by the Analyse des Pratiques Musicales research group, STMS Lab (IRCAM, CNRS, Sorbonne Université) With the support of Société Française d’Analyse Musicale, and the Collegium Musicæ SPECTRALISMS 2019 “Vous avez dit spectral?” In March 2017, the Faculty the specifics of significant musical works that empha- of Music at the University of Oxford, in association sise both the organological and analytical properties with IRCAM, organised Spectralisms, a conference of spectralism in a broad sense (from Scelsi to Criton devoted entirely to the discussion of issues in spectral by way of Rădulescu and Grisey). music (http://www.music.ox.ac.uk/spectralisms/). The wide range of ideas engaged over the two days of Over the two years of preparation, we have been the conference reflected the