The Clifton Institute 2018 Biodiversity Survey Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loggerhead Shrike

EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE Grasslands Ecosystem Initiative Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center U.S. Geological Survey Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 This report is one in a series of literature syntheses on North American grassland birds. The need for these reports was identified by the Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (PPJV), a part of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The PPJV recently adopted a new goal, to stabilize or increase populations of declining grassland- and wetland-associated wildlife species in the Prairie Pothole Region. To further that objective, it is essential to understand the habitat needs of birds other than waterfowl, and how management practices affect their habitats. The focus of these reports is on management of breeding habitat, particularly in the northern Great Plains. Suggested citation: Dechant, J. A., M. L. Sondreal, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, M. P. Nenneman, A. L. Zimmerman, and B. R. Euliss. 1998 (revised 2002). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Loggerhead Shrike. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. 19 pages. Species for which syntheses are available or are in preparation: American Bittern Grasshopper Sparrow Mountain Plover Baird’s Sparrow Marbled Godwit Henslow’s Sparrow Long-billed Curlew Le Conte’s Sparrow Willet Nelson’s Sharp-tailed Sparrow Wilson’s Phalarope Vesper Sparrow Upland Sandpiper Savannah Sparrow Greater Prairie-Chicken Lark Sparrow Lesser Prairie-Chicken Field Sparrow Northern Harrier Clay-colored Sparrow Swainson’s Hawk Chestnut-collared Longspur Ferruginous Hawk McCown’s Longspur Short-eared Owl Dickcissel Burrowing Owl Lark Bunting Horned Lark Bobolink Sedge Wren Eastern Meadowlark Loggerhead Shrike Western Meadowlark Sprague’s Pipit Brown-headed Cowbird EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: LOGGERHEAD SHRIKE Jill A. -

The Maryland Entomologist

THE MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST Insect and related-arthropod studies in the Mid-Atlantic region Volume 7, Number 2 September 2018 September 2018 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 7, Number 2 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.mdentsoc.org Executive Committee: President Frederick Paras Vice President Philip J. Kean Secretary Janet A. Lydon Treasurer Edgar A. Cohen, Jr. Historian (vacant) Journal Editor Eugene J. Scarpulla E-newsletter Editors Aditi Dubey The Maryland Entomological Society (MES) was founded in November 1971, to promote the science of entomology in all its sub-disciplines; to provide a common meeting venue for professional and amateur entomologists residing in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and nearby areas; to issue a periodical and other publications dealing with entomology; and to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information through its meetings and publications. The MES was incorporated in April 1982 and is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, scientific organization. The MES logo features an illustration of Euphydryas phaëton (Drury) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), the Baltimore Checkerspot, with its generic name above and its specific epithet below (both in capital letters), all on a pale green field; all these are within a yellow ring double-bordered by red, bearing the message “● Maryland Entomological Society ● 1971 ●”. All of this is positioned above the Shield of the State of Maryland. In 1973, the Baltimore Checkerspot was named the official insect of the State of Maryland through the efforts of many MES members. Membership in the MES is open to all persons interested in the study of entomology. All members receive the annual journal, The Maryland Entomologist, and the monthly e-newsletter, Phaëton. -

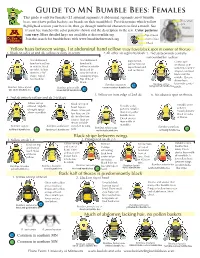

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Wildlife Habitat Plan

WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALITY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY WILDLIFE HABITAT PLAN City of Novi, Michigan A QUALIlY OF LIFE FOR THE 21ST CENTURY JUNE 1993 Prepared By: Wildlife Management Services Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. JCK & Associates, Inc. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS City Council Matthew C. Ouinn, Mayor Hugh C. Crawford, Mayor ProTem Nancy C. Cassis Carol A. Mason Tim Pope Robert D. Schmid Joseph G. Toth Planning Commission Kathleen S. McLallen, * Chairman John P. Balagna, Vice Chairman lodia Richards, Secretary Richard J. Clark Glen Bonaventura Laura J. lorenzo* Robert Mitzel* Timothy Gilberg Robert Taub City Manager Edward F. Kriewall Director of Planning and Community Development James R. Wahl Planning Consultant Team Wildlife Management Services - 640 Starkweather Plymouth, MI. 48170 Kevin Clark, Urban Wildlife Specialist Adrienne Kral, Wildlife Biologist Ashley long, Field Research Assistant Brandon M. Rogers and Associates, P.C. - 20490 Harper Ave. Harper Woods, MI. 48225 Unda C. lemke, RlA, ASLA JCK & Associates, Inc. - 45650 Grand River Ave. Novi, MI. 48374 Susan Tepatti, Water Resources Specialist * Participated with the Planning Consultant Team in developing the study. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii PREFACE vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY viii FRAGMENTATION OF NATURAL RESOURCES " ., , 1 Consequences ............................................ .. 1 Effects Of Forest Fragmentation 2 Edges 2 Reduction of habitat 2 SPECIES SAMPLING TECHNIQUES ................................ .. 3 Methodology 3 Survey Targets ............................................ ., 6 Ranking System ., , 7 Core Reserves . .. 7 Wildlife Movement Corridor .............................. .. 9 FIELD SURVEY RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS , 9 Analysis Results ................................ .. 9 Core Reserves . .. 9 Findings and Recommendations , 9 WALLED LAKE CORE RESERVE - DETAILED STUDy.... .. .... .. .... .. 19 Results and Recommendations ............................... .. 21 GUIDELINES TO ECOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE PLANNING AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION. -

Poaceae Pollen from Southern Brazil: Distinguishing Grasslands (Campos) from Forests by Analyzing a Diverse Range of Poaceae Species

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 06 December 2016 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01833 Poaceae Pollen from Southern Brazil: Distinguishing Grasslands (Campos) from Forests by Analyzing a Diverse Range of Poaceae Species Jefferson N. Radaeski 1, 2, Soraia G. Bauermann 2* and Antonio B. Pereira 1 1 Universidade Federal do Pampa, São Gabriel, Brazil, 2 Laboratório de Palinologia da Universidade Luterana do Brasil–ULBRA, Universidade Luterana do Brazil, Canoas, Brazil This aim of this study was to distinguish grasslands from forests in southern Brazil by analyzing Poaceae pollen grains. Through light microscopy analysis, we measured the size of the pollen grain, pore, and annulus from 68 species of Rio Grande do Sul. Measurements were recorded of 10 forest species and 58 grassland species, representing all tribes of the Poaceae in Rio Grande do Sul. We measured the polar, equatorial, pore, and annulus diameter. Results of statistical tests showed that arboreous forest species have larger pollen grain sizes than grassland and herbaceous forest species, and in particular there are strongly significant differences between arboreous and grassland species. Discriminant analysis identified three distinct groups representing Edited by: each vegetation type. Through the pollen measurements we established three pollen Encarni Montoya, types: larger grains (>46 µm), from the Bambuseae pollen type, medium-sized grains Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume < Almera (CSIC), Spain (46–22 µm), from herbaceous pollen type, and small grains ( 22 µm), from grassland Reviewed by: pollen type. The results of our compiled Poaceae pollen dataset may be applied to the José Tasso Felix Guimarães, fossil pollen of Quaternary sediments. Vale Institute of Technology, Brazil Lisa Schüler-Goldbach, Keywords: pollen morphology, grasses, pampa, South America, Atlantic forest, bamboo pollen Göttingen University, Germany *Correspondence: Jefferson N. -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan

Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan i Empire State Native Pollinator Survey Study Plan June 2017 Matthew D. Schlesinger Erin L. White Jeffrey D. Corser Please cite this report as follows: Schlesinger, M.D., E.L. White, and J.D. Corser. 2017. Empire State Native pollinator survey study plan. New York Natural Heritage Program, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Albany, NY. Cover photos: Sanderson Bumble Bee (Bombus sandersoni) and flower longhorn (Clytus ruricola) by Larry Master, www.masterimages.org; Azalea sphinx moth (Darapsa choerilus) and Syrphus fly by Stephen Diehl and Vici Zaremba. ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Background: Rising Buzz and a Swarm of Pollinator Plans .................................................................... 1 Advisors and Taxonomic Experts .............................................................................................................. 1 Goal of the Survey ........................................................................................................................................ 2 General Sampling Design ............................................................................................................................. 2 The Role of Citizen Science ......................................................................................................................... 2 Focal Taxa .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Moorhead Ph 1 Final Report

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Ecological Assessment of a Wetlands Mitigation Bank August 2001 (Phase I: Baseline Ecological Conditions and Initial Restoration Efforts) 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Kevin K. Moorhead, Irene M. Rossell, C. Reed Rossell, Jr., and James W. Petranka 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Departments of Environmental Studies and Biology University of North Carolina at Asheville Asheville, NC 28804 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Research and Special Programs Administration May 1, 1994 – September 30, 2001 400 7th Street, SW Washington, DC 20590-0001 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation and the North Carolina Department of Transportation, through the Center for Transportation and the Environment, NC State University. 16. Abstract The Tulula Wetlands Mitigation Bank, the first wetlands mitigation bank in the Blue Ridge Province of North Carolina, was created to compensate for losses resulting from highway projects in western North Carolina. The overall objective for the Tulula Wetlands Mitigation Bank has been to restore the functional and structural characteristics of the wetlands. Specific ecological restoration objectives of this Phase I study included: 1) reestablishing site hydrology by realigning the stream channel and filling drainage ditches; 2) recontouring the floodplain by removing spoil that resulted from creation of the golf ponds and dredging of the creek; 3) improving breeding habitat for amphibians by constructing vernal ponds; and 4) reestablishing floodplain and fen plant communities. -

El Género Muhlenbergia

www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm CaldasiaGiraldo-Cañas 31(2):269-302. & Peterson 2009 EL GÉNERO MUHLENBERGIA (POACEAE: CHLORIDOIDEAE: CYNODONTEAE: MUHLENBERGIINAE) EN COLOMBIA1 The genus Muhlenbergia (Poaceae: Chloridoideae: Cynodonteae: Muhlenbergiinae) in Colombia DIEGO GIRALDO-CAÑAS Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Apartado 7495, Bogotá D.C., Colombia. [email protected] PAUL M. PETERSON Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, U.S.A. [email protected] RESUMEN Se presenta un estudio taxonómico de las especies colombianas del género Muhlenbergia. Se analizan diversos aspectos relativos a la clasificación, la nomenclatura y la variación morfológica de los caracteres. El género Muhlenbergia está representado en Colombia por 14 especies. Las especies Aegopogon bryophilus Döll, Aegopogon cenchroides Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd., Lycurus phalaroides Kunth y Pereilema crinitum J. Presl se transfi eren al género Muhlenbergia. El binomio Muhlenbergia cleefi i Lægaard se reduce a la sinonimia de Muhlenbergia fastigiata (J. Presl) Henrard. Las especies Muhlenbergia beyrichiana Kunth, Muhlenbergia ciliata (Kunth) Trin. y Muhlenbergia nigra Hitchc. se excluyen de la fl ora de Colombia. Se presentan las claves para reconocer las especies presentes en Colombia, así como también las descripciones de éstas, sus sinónimos, la distribución geográfi ca, se comentan algunas observaciones morfológicas y ecológicas, los usos y los números cromosómicos. Del tratamiento taxonómico se excluyen las especies Muhlenbergia erectifolia SwallenSwallen [[== Ortachne erectifolia (Swallen)(Swallen) CClayton]layton] y Muhlenbergia wallisii Mez [= Agrostopoa wallisii (Mez) P. M. Peterson, Soreng & Davidse]. Palabras clave. Aegopogon, Lycurus, Muhlenbergia, Pereilema, Chloridoideae, Poaceae, Gramíneas neotropicales, Flora de Colombia. -

A Field Guide Introduction Welcome! As Avid Birders from Penn State University, We Are Happy You Have an Interest in Learning More About Birds

Birds of Pennsylvania A Field Guide Introduction Welcome! As avid birders from Penn State University, we are happy you have an interest in learning more about birds. The following field guide is similar to the ones used by ornithologists (professional birders!) to identify the birds they see in the field. If you read a word in the field guide that you don’t understand, come back to this page to read about what it means, or ask a bird loving adult. Have fun! Glossary Scientific Name – This is the Latin name for a bird. It is useful when talking about a bird with someone who is not from our area, and may know it by a different name. Habitat – This is a description of the area that a bird likes to live in. It may include plant types, temperatures, and other things the bird may need to survive. Diet – This includes the types of food that a bird eats. Some eat mostly insects, while others prefer fruit. Range – The range of a bird is the area of the world where a species of bird lives. It is also shown on a map in this field guide. Migration – This is the journey that most birds take every year, where they fly south during the winter to escape the cold and fly north during the summer to breed and lay eggs. Plumage – This is another word for feathers! Parts of a Bird Bill Forehead Nape Throat Wing Rump Tail Breast Northern Flicker Scientific Name: Colaptes auratus Habitat: Northern Flickers are often found in woodlands, forest edges and open fields with scattered trees. -

TPM/IPM Weekly Report for Arborists, Landscape Managers & Nursery Managers

TPM/IPM Weekly Report for Arborists, Landscape Managers & Nursery Managers Commercial Horticulture July 12, 2019 In This Issue... Coordinator Weekly IPM Report: Stanton Gill, Extension Specialist, IPM for Nursery, Greenhouse and Managed - Cannibalistic predators Landscapes, [email protected]. 301-596-9413 (office) or 410-868-9400 (cell) - Impatiens downy mildew - Peach tree borer - Perennial program Regular Contributors: - Seed pods on magnolia Pest and Beneficial Insect Information: Stanton Gill and Paula Shrewsbury (Extension - Summer fruit tree pruning Specialists) and Nancy Harding, Faculty Research Assistant - Chiggers Disease Information: Karen Rane (Plant Pathologist) and David Clement (Extension - Powdery mildew on crape Specialist) myrtle Weed of the Week: Chuck Schuster (Extension Educator, Montgomery County) - Crape myrtle problems Cultural Information: Ginny Rosenkranz (Extension Educator, Wicomico/Worcester/ - Orangestriped oakworm Somerset Counties) - Japanese beetles and green Fertility Management: Andrew Ristvey (Extension Specialist, Wye Research & June beetles Education Center) - Redheaded pine sawflies Design, Layout and Editing: Suzanne Klick (Technician, CMREC) - Fall webworms - Yellownecked caterpillars - Rust and powdery mildew Cannibalistic Predators - Barklice (pscocids) By: Stanton Gill - Photos: deer, fall webworm adult, dobsonfly, tobacco Marie Rojas, IPM Scout, sent in hornworm, and mites some pictures of lady bird beetle Beneficial of the Week: Black larvae feeding on eggs in the cluster and gold bumble bee from which they hatched. I put these Weed of the Week: Small pictures out to entomologists across carpetgrass the US and received responses Plant of the Week: Prunus laurocerasus ‘schipkaensis’ noting that this activity is common. Pest Predictions Robin Rosetta sent in a picture from Degree Days Oregon with a larvae feeding on its Announcements sibling’s egg.