Robert Burns and the Merry Muses of Caledonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letters of Robert Burns 1

The Letters of Robert Burns 1 The Letters of Robert Burns The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Robert Burns, by Robert Burns #3 in our series by Robert Burns Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. The Letters of Robert Burns 2 **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Letters of Robert Burns Author: Robert Burns Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9863] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 25, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr and PG Distributed Proofreaders BURNS'S LETTERS. THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, SELECTED AND ARRANGED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY J. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

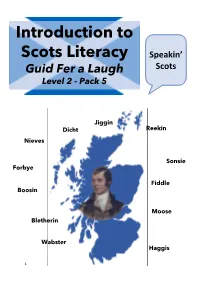

Introduction to Scots Literacy

Introduction to Scots Literacy Speakin’ Scots Guid Fer a Laugh Level 2 - Pack 5 Jiggin Dicht Reekin Nieves Sonsie Forbye Fiddle Boosin Moose Bletherin Wabster Haggis 1 Introduction to Guid Fer A Laugh We are part of the City of Edinburgh Council, South West Adult Learning team and usually deliver ‘Guid Fer a Laugh’ sessions for community groups in South West Edinburgh. Unfortunately, we are unable to meet groups due to Covid-19. Good news though, we have adapted some of the material and we hope you will join in at home. Development of Packs We plan to develop packs from beginner level 1 to 5. Participants will gradually increase in confidence and by level 5, should be able to: read, recognise, understand and write in Scots. Distribution During Covid-19 During Covid-19 restrictions we are emailing packs to community forums, organisations, groups and individuals. Using the packs The packs can be done in pairs, small groups or individually. They are being used by: families, carers, support workers and individuals. The activities are suitable for all adults but particularly those who do not have access to computer and internet. Adapting Packs The packs can be adapted to suit participants needs. For example, the Pilmeny Development Project used The Scot Literacy Pack as part of a St Andrews Day Activity Pack which was posted out to 65 local older people. In the pack they included the Scot Literacy Pack 1 and 2, crosswords, short bread and a blue pen. Please see photo. 2 The Aims of the Session – Whit’s it a’aboot? • it’s about learning Scots language and auld words • takes a look at Scots comedy, songs, poetry and writing • hae a guid laugh at ourselves and others Feedback fae folk This is pack number five and we move on a little to Level 2. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

Auld Lang Syne, 1799–1999

Press Contacts Patrick Milliman 212.590.0310, [email protected] Alanna Schindewolf 212.590.0311, [email protected] POET ROBERT BURNS AND THE CREATION OF THE BELOVED NEW YEAR’S EVE SONG “AULD LANG SYNE” IS THE SUBJECT OF A NEW EXHIBITION AT THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM SHOW INCLUDES A RARE MANUSCRIPT OF “AULD LAND SYNE” IN BURNS’S HAND, A CACHE OF HIS LETTERS RELATED TO ITS ORIGIN, AND EARLY PRINTED EDITIONS OF THE SONG Robert Burns and “Auld Lang Syne” December 9, 2011–February 5, 2012 New York, NY, December 6, 2011—Each New Year’s Eve, millions raise their voices in a chorus of “Auld Lang Syne,” standing with friends and looking back with nostalgia on days past. But how did a traditional Scots folk song—with lyrics that many people scarcely understand—emerge as one of the world’s most enduring popular songs? It was Robert Burns (1759–1796), the great eighteenth-century Scottish poet, who transformed the old verses into the version we know today. Robert Burns and “Auld Lang Syne” at The Morgan Library & Museum untangles the complex origins of the song that has become, over time, a globally shared expression of friendship and longing. On view from December 9, 2011 at noon, through February 5, 2012, the exhibition features rare printed editions, a manuscript of the song in the poet’s Robert Burns (1759–1796) own hand, and selections from the Morgan’s important Engraved portrait by Paton Thomson London and Edinburgh: Published by collection of Burns letters—the largest in the world. -

Comprehension – Robert Burns – Y5m/Y6d – Brainbox Remembering Burns Robert Burns May Be Gone, but He Will Never Be Forgotten

Robert Burns Who is He? Robert Burns is one of Scotland’s most famous poets and song writers. He is widely regarded as the National Poet of Scotland. He was born in Ayrshire on the 25th January, 1759. Burns was from a large family; he had six other brothers and sisters. He was also known as Rabbie Burns or the Ploughman Poet. Childhood Burns was the son of a tenant farmer. As a child, Burns had to work incredibly long hours on the farm to help out. This meant that he didn’t spend much time at school. Even though his family were poor, his father made sure that Burns had a good education. As a young man, Burns enjoyed reading poetry and listening to music. He also enjoyed listening to his mother sing old Scottish songs to him. He soon discovered that he had a talent for writing and wrote his first song, Handsome Nell, at the age of fifteen. Handsome Nell was a love song, inspired by a farm servant named Nellie Kilpatrick. Becoming Famous In 1786, he planned to emigrate to Jamaica. His plans were changed when a collection of his songs and poems were published. The first edition of his poetry was known as the Kilmarnock edition. They were a huge hit and sold out within a month. Burns suddenly became very popular and famous. That same year, Burns moved to Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. He was made very welcome by the wealthy and powerful people who lived there. He enjoyed going to parties and living the life of a celebrity. -

"Auld Lang Syne" G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy Robert Burns Collections 3-1-2018 "Auld Lang Syne" G. Ross Roy University of South Carolina - Columbia Publication Info 2018, pages 77-83. (c) G. Ross Roy, 1984; Estate of G. Ross Roy; and Studies in Scottish Literature, 2019. First published as introduction to Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, Scottish Poetry Reprints, 5 (Greenock: Black Pennell, 1984). This Chapter is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Essays on Robert Burns by G. Ross Roy by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “AULD LANG SYNE” (1984) A good case can be made that “Auld Lang Syne” is the best known “English” song in the world, & perhaps the best known in any language if we except national anthems. The song is certainly known throughout the English-speaking world, including countries which were formerly part of the British Empire. It is also known in most European countries, including Russia, as well as in China and Japan. Before and during the lifetime of Robert Burns the traditional Scottish song of parting was “Gude Night and Joy be wi’ You a’,” and there is evidence that despite “Auld Lang Syne” Burns continued to think of the older song as such. He wrote to James Johnson, for whom he was writing and collecting Scottish songs to be published in The Scots Musical Museum (6 vols. Edinburgh, 1787-1803) about “Gude Night” in 1795, “let this be your last song of all the Collection,” and this more than six years after he had written “Auld Lang Syne.” When Johnson published Burns’s song it enjoyed no special place in the Museum, but he followed the poet’s counsel with respect to “Gude Night,” placing it at the end of the sixth volume. -

The Prayer of Holy Willie

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications English Language and Literatures, Department of 7-7-2015 The rP ayer of Holy Willie: A canting, hypocritical, Kirk Elder Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/engl_facpub Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Publication Info Published in 2015. Introduction and editorial matter copyright (c) Patrick Scott nda Scottish Poetry Reprint Series, 2015. This Book is brought to you by the English Language and Literatures, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PRAYER OF HOLY WILLIE by ROBERT BURNS Scottish Poetry Reprints Series An occasional series edited by G. Ross Roy, 1970-1996 1. The Life and Death of the Piper of Kilbarchan, by Robert Semphill, edited by G. Ross Roy (Edinburgh: Tragara Press, 1970). 2. Peblis, to the Play, edited by A. M. Kinghorn (London: Quarto Press, 1974). 3. Archibald Cameron’s Lament, edited by G. Ross Roy (London: Quarto Press, 1977). 4. Tam o’ Shanter, A Tale, by Robert Burns, ed. By G. Ross Roy from the Afton Manuscript (London: Quarto Press, 1979). 5. Auld Lang Syne, by Robert Burns, edited by G. Ross Roy, music transcriptions by Laurel E. Thompson and Jonathan D. Ensiminger (Greenock: Black Pennell Press, 1984). 6. The Origin of Species, by Lord Neaves, ed. Patrick Scott (London: Quarto Press, 1986). 7. Robert Burns, A Poem, by Iain Crichton Smith (Edinburgh: Morning Star, 1996). -

Burns Chronicle 1935

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1935 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Mr Jim Henderson, Burns Club of London The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE . AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 189 I PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES: VOLUME X THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK 1935 Price Three shillings . "HURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER A "WAUGH" CHIEFTAIN To ensure a succeuful BURNS DINNER, or any dinner, you cannot do better than get your HAGGIS supplies from GEORGE WAUGH (ESTB. 1840) MAKER OF THE BEST SCOTCH HAGGIS The ingredients used are the finest obtainable and very rich in VITAMINS, rendering it a very valuable food. DELICIOUS AND DISTINCTIVE "A Glorious Dish" For delivery in the British Isles, any quantity supplied from . ! lb. to CHIEFTAIN size. WAUGH'S For EXPORT. 1 lb. Tin 2/- in skins within HAGGIS - 2 lb. " 3/6 hermetically HEAT IT 3 lb." 5/- AND sealed tins. EAT IT plus post. Write, wire, or 'phone GEORGE WAUGH 110 Nicolson Street. EDINBURGH 8 Kitchens: Telegrams: Haggiston, Broughton Rd. " Haggis," Edin. Phone 25778 Phone 42849 "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOMES, MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. In Memory of the Poet Burns for Deserving Old People . .. That greatest of benevolent institutions established in honour of Robert Bl-\ rns."-Glasgow Herald here are now sixteen modern comfortable houses . for the benefit of deserving old folks. The site is T. an ideal one in the heart of the Burns Country.