James Currie's Editing of the Correspondence of Robert Burns Robert D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Robert Burns, His Medical Friends, Attendants and Biographer*

ROBERT BURNS, HIS MEDICAL FRIENDS, ATTENDANTS AND BIOGRAPHER* By H. B. ANDERSON, M.D. TORONTO NE hundred and twenty-seven untimely death was a mystery for which fl years have elapsed since Dr. James some explanation had to be proffered. I Currie, f .r .s ., of Liverpool, pub- Two incidents, however, discredit Syme Iished the first and greatest biog- as a dependable witness: the sword incident, raphy of Robert Burns. on the occasion of his reproving the poet Dr. Currie had met the poet but once and regarding his habits, of which there are then only for a few minutes in the streets several conflicting accounts, and his apoc- of Dumfries, so that he was entirely depend- ryphal version of the circumstances under ent on others for the information on which which “Scots Wha Hae” was produced he based his opinions of the character and during the Galloway tour. In regard to the habits of Burns. A few days after Burns’ latter incident, the letter Burns wrote death he wrote to John Syme, “Stamp-office Thomson in forwarding the poem effectually Johnnie,” an old college friend then living disposes of Syme’s fabrication. in Dumfries: “ By what I have heard, he was As Burns’ biographer, Dr. Currie is known not very correct in his conduct, and a report to have been actuated by admiration, goes about that he died of the effects of friendship, and the benevolent purpose of habitual drinking.” But doubting the truth- helping to provide for the widow and family; fulness of the current gossip, he asks Syme and it is quite evident that he was willing, pointedly “What did Burns die of?” It is if not anxious, to undertake the task. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

Robert Burns World Federation Limited

Robert Burns World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Ian McIntyre The digital conversion was provided by Solway Offset Services Ltd by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.solwayprint.co.uk BURNS CHRONICLE 2018 Edited by Bill Dawson Burns Chronicle founded 1892 The Robert Burns World Federation © Burns Chronicle 2018, all rights reserved. Copyright rests with the Robert Burns World Federation unless otherwise stated. The Robert Burns World Federation Ltd does not accept responsibility for statements made or opinions expressed in the Burns Chronicle, contributors are responsible for articles signed by them; the Editor is responsible for articles initialled or signed by him and for those unsigned. All communications should be addressed to the Federation office. The Robert Burns World Federation Ltd. Tel. 01563 572469 Email [email protected] Web www.rbwf.org.uk Editorial Contacts & addresses for contributions; [email protected] [email protected] Books for review to the office The Robert Burns World Federation, 3a John Dickie Street, Kilmarnock, KA1 1HW ISBN 978-1-907931-68-0 Printed in Scotland by Solway Print, Dumfries 2018 Burns Chronicle Editor Bill Dawson The Robert Burns World Federation Kilmarnock www.rbwf.org.uk The mission of the Chronicle remains the furtherance of knowledge about Robert Burns and its publication in a form that is both academically responsible and clearly communicated for the broader Burnsian community. In reviewing, and helping prospective contributors develop, suitable articles to fulfil this mission, the Editor now has the support of an Editorial Advisory Board. -

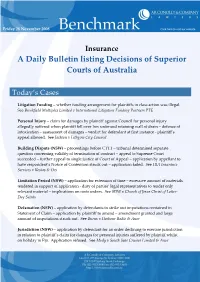

A Daily Bulletin Listing Decisions of Superior Courts of Australia

Friday 28 November 2008 Click here to visit our website Insurance A Daily Bulletin listing Decisions of Superior Courts of Australia Today’s Cases Litigation Funding – whether funding arrangement for plaintiffs in class action was illegal. See Brookfield Multiplex Limited v International Litigation Funding Partners PTE Personal Injury – claim for damages by plaintiff against Council for personal injury allegedly suffered when plaintiff fell over low unfenced retaining wall of drain – defence of intoxication – assessment of damages – verdict for defendant at first instance - plaintiff’s appeal allowed. See Jackson v Lithgow City Council Building Dispute (NSW) – proceedings before CTTT – tribunal determined separate question concerning validity of termination of contract – appeal to Supreme Court succeeded – further appeal to single justice of Court of Appeal – application by appellant to have respondent’s Notice of Contention struck out – application failed. See HIA Insurance Services v Kostas & Ors Limitation Period (NSW) – application for extension of time – excessive amount of materials tendered in support of application - duty of parties’ legal representatives to tender only relevant material – implications on costs orders. See SDW v Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- Day Saints Defamation (NSW) – application by defendants to strike out imputations contained in Statement of Claim – application by plaintiff to amend – amendment granted and large amount of imputations struck out. See Burns v Harbour Radio & Anor Jurisdiction (NSW) – application by defendant for an order declining to exercise jurisdiction in relation to plaintiff’s claim for damages for personal injuries suffered by plaintiff whilst on holiday in Fiji. Application refused. See Mody v South Seas Cruises Limited & Anor Motor Accident (NSW) – sections 108 & 109: Motor Accidents Compensation Act 1999 – whether “full and satisfactory” explanation – leave to commence proceedings granted. -

Burns Chronicle 1935

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1935 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Mr Jim Henderson, Burns Club of London The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE . AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 189 I PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES: VOLUME X THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK 1935 Price Three shillings . "HURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER A "WAUGH" CHIEFTAIN To ensure a succeuful BURNS DINNER, or any dinner, you cannot do better than get your HAGGIS supplies from GEORGE WAUGH (ESTB. 1840) MAKER OF THE BEST SCOTCH HAGGIS The ingredients used are the finest obtainable and very rich in VITAMINS, rendering it a very valuable food. DELICIOUS AND DISTINCTIVE "A Glorious Dish" For delivery in the British Isles, any quantity supplied from . ! lb. to CHIEFTAIN size. WAUGH'S For EXPORT. 1 lb. Tin 2/- in skins within HAGGIS - 2 lb. " 3/6 hermetically HEAT IT 3 lb." 5/- AND sealed tins. EAT IT plus post. Write, wire, or 'phone GEORGE WAUGH 110 Nicolson Street. EDINBURGH 8 Kitchens: Telegrams: Haggiston, Broughton Rd. " Haggis," Edin. Phone 25778 Phone 42849 "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOMES, MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. In Memory of the Poet Burns for Deserving Old People . .. That greatest of benevolent institutions established in honour of Robert Bl-\ rns."-Glasgow Herald here are now sixteen modern comfortable houses . for the benefit of deserving old folks. The site is T. an ideal one in the heart of the Burns Country. -

The Burns Almanac for 1897

J AN U AR Y . “ ” This Tim e wi n ds 1 0 day etc . Composed 79 . 1 Letter to Mrs . Dunlop , 7 93 . f 1 Rev . Andrew Je frey died 795 . “ Co f G ra ha m py o Epistle to Robert , of Fintry , sent to 1 8 . Dr . Blacklock , 7 9 n 1 8 1 Al exa der Fraser Tytler , died 3 . ” t Copy of Robin Shure i n Hairst , se nt to Rober Ainslie, 1 789 . ’ d . Gilbert Burns initiate into St James Lodge , F A M 1 786 . fi e Th e poet de nes his religious Cr ed in a letter to Clarinda , 1 788 . ” Highland Mary , published by Alexander Gardner , 1 8 . Paisley , 94 1 1 8 . Robert Graham of Fintry , died 5 z 1 8 Dr . John Ma cken ie , died 3 7 . ’ o n t . d The p et presen t at Grand Maso ic Meeting , S An rew s 1 8 Lodge , Edinburgh , 7 7 . u z 1 8 . Y . Albany , (N ) Burns Cl b , organi ed 54 8 2 1 0 . Mrs . Burnes , mother of the poet , died The poet describes his favorite authors i n a letter to Joh n 1 8 . Murdoch , 7 3 U 1 0 . The Scottish Parliament san ctions the nion , 7 7 1 1 Letter to Peter Hill , 79 . ” B r 2 i a n a 1 1 . u n s v . u 8 , ol , iss ed 9 1 88 Letter to Clarinda , 7 . Mrs . Candlish , the Miss Smith of the Mauchline Belles , 1 8 died 54 . -

Hail Thy Palaces and Tow'rs'

ROBERT BURNS n Scotland’s Year of ‘All hail Homecoming, and with the associated celebrations of our national bard’s 250th anniversary, it is worth thy palaces considering what Robert Burns hadI to say about his land and heritage. His urge to write of all things Scottish is clear: ‘The appelation of a Scotch Bard and tow’rs’ is by far my highest pride… Scottish scenes, and Scottish story are the themes I could wish to sing. I have no greater, The life and times of Robert Burns are stories often told, but no dearer aim than to have it in my less well known are the connections that bind ‘Caledonia’s power… to make leisurely pilgrimages through Caledonia; to sit on the fields of Bard’ to many properties now in Historic Scotland care. her battles; to wander on the romantic Ken Simpson and Lorna Ewan take us on a guided tour banks of her rivers; and to muse by the stately tower or venerable ruins, once the honored abodes of her heroes.’ Of Melrose, the poet noted ‘dine there and visit that far-fam’d glorious ruins’ CK O A statue of Burns, tterst U ‘Caledonia’s Bard’ sh XXXXXXXX 24 | HISTORIC SCOTLAND | SPRING 2009 But despite Burns’s tours around described the view into Alloway Kirk as tunes and pickt up Scotch songs, Scotland, and into the north of England, ‘through the ribs and arches of an old Jacobite anecdotes…’ his description of the built landscape gothic window’. However, of Burns’s travels had been prompted rarely extended beyond the south west Edinburgh’s architecture and form, he by his successful sojourn in the capital lowlands with which he was so familiar. -

Burns Chronicle 1938

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1938 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Frank Shaw The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE AND CLUB DIRECTORY INSTITUTED 1 8 9 1 PUBLISHED ANNUALLY SECOND SERIES : VOLUME XIII THE BURNS FEDERATION KILMARNOCK I 9 3 8 Price Three shillings "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISER A "WAUGH " CHIEFTAIN To ensure a successful BURNS DINNBR, or any dinner, you cannot do better than get your HAGGIS supplies from GEORGE WAUGH MAKER OF THE BEST SCOTCH HAGGIS since 1840 DELICIOUS AND. DISTINCTIVE The ingredients used are . the finest obtainable and very rich in VITAMINS, rendering it a very valuable food. A GLORIOUS DISH For delivery in the British Isles, any quantity supplied from l lb. to CHIEFTAIN size. For Export in skins within hermetically sealed Tins-postage extra. 1 lb. Tin 2/- 2 " " 3/6 3 " " 6/· GEORGE WAUGH 110 NICOLSON ST., EDINBURGH, 8 Kitchelll: TeJesmuns: Haggiston, Broughton Rd. " Haggis,"A Edinburgh Phone 25778 Pbone42849 "BURNS CHRONICLE" ADVERTISE]{ NATIONAL BURNS MEMORIAL COTTAGE HOMES, MAUCHLINE, AYRSHIRE. In Memory of the Poet Burns for Deserving Old People. "That greatest of benevolent Institutions established . In honour of Robert Burns." -6/aagow Herald. There are now eighteen modern . comfortable houses for the benefit of deserving old folks. Two further cottages are in course of erection. The site is an ideal one in the heart of the Burns Country. The Cottagers, after careful selection, get the houses free of rent and taxes and an annual allowance. -

A Bibliography of Robert Burns for the 21St Century: 1786-1802

A Bibliography of Robert Burns for the 21st Century: 1786-1802 Craig Lamont 2018 Introduction THIS WORK will provide the beginnings of an overdue renewal into the bibliographical study of the main editions of Robert Burns. The aim is to provide comprehensive details, especially concerning the contents of the editions, which have been generally overlooked by previous bibliographers. It is hoped that this new methodology will benefit future researchers and readers of Robert Burns. The work is linked with the AHRC- funded project, ‘Editing Robert Burns for the 21st Century’ at the University of Glasgow, currently producing the multi-volume Oxford Edition of the Works of Robert Burns. Following the first phase of the work, further research was kindly funded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh through a Small Research Grant: ‘The Early Editions of Robert Burns, 1786-1802: towards a new descriptive bibliography’ (PI: Lamont), opening up the possibility for consultations in other collections. The principal reference in constructing this bibliography is J. W. Egerer’s A Bibliography of Robert Burns (1964). Other bibliographies, catalogues, books, and articles relative to this area will also be consulted, and any insights gained from these will be noted throughout. While Egerer’s chief aim in his bibliography ‘is to emphasize the first appearances in print of Burns’s writings,’ this work seeks to provide comprehensive details about each main edition, as well as renewing or correcting previous or outdated assumptions about first appearances and authorship of certain poems and songs. The method for doing this was refined over time, but the end result is hopefully easy to follow, especially with the focus on the contents, ie. -

Fifteen Songs of Robert Burns

FIFTEEN SOMGS OF ROBERT BURNS LOIS G. WILLIAMS B. A., University of California, 1963 A MASTER'S REPORT suijmltted in partial fulfillioent of the requirements for the degree V MASTER OF ARTS Department of English KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1966 Approved by: .tl^±Scmierv^^ Major Professor The great fascination vlth £olk song ^ilch began In the eighteenth century and grew to gigantic proportions in the twentieth con8taxU;ly seeks new avenues of interest. Ei^teenth-century collectors and editors amassed large collections of songs. Although the collector was concerned with the antiquity of a song, he was inclined to edit elements of "barbarista." Collectors of the twentieth century, on the other hand, have been concerned with tracing the genealogies of songs, with establishing the ''authenticity" of words or tune. As everyone knows, a folk song must be very old, must betray no polished literary skill, and must certainly be anonymous. Contenqiorary collectors would probably disregard the songs o£ Robert Bums, since, after all, they are not really old, are not works of an unskilled literary hand, and are not even sanctified by anonymity. A song has two equally important elemeots: words and noisic. Until recently, song collectors have been primarily Interested in words because of the difficulties in tracing old tunes which are caused by notational problems and absence of historical records. In the divorce of these two elements, as Gavin Greig points out, both have suffered: Taken apart from the music the words have come to be judged mainly by literary standards. But 'good is good for what it suits'; and the words of a song being intended for singing cannot fairly be judged apart from the music.