Episode Twenty Three Chapter 7Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WRECK DIVING™ ...Uncover the Past Magazine

WRECK DIVING™ ...uncover the past Magazine Graf Zeppelin • La Galga • Mystery Ship • San Francisco Maru Scapa Flow • Treasure Hunting Part I • U-869 Part III • Ville de Dieppe WRECK DIVING MAGAZINE The Fate of the U-869 Reexamined Part III SanSan FranciscoFrancisco MaruMaru:: TheThe MillionMillion DollarDollar WreckWreck ofof TRUKTRUK LAGOONLAGOON Issue 19 A Quarterly Publication U-869 In In our previousour articles, we described the discovery and the long road to the identification ofU-869 off the The Fate Of New Jersey coast. We also examined the revised histories issued by the US Coast Guard Historical Center and the US Naval Historical Center, both of which claimed The U-869 the sinking was a result of a depth charge attack by two US Navy vessels in 1945. The conclusion we reached was that the attack by the destroyers was most likely Reexamined, Part on the already-wrecked U-869. If our conclusion is correct, then how did the U-869 come to be on the III bottom of the Atlantic? The Loss of the German Submarine Early Theories The most effective and successful branch of the German By John Chatterton, Richie Kohler, and John Yurga Navy in World War II was the U-boat arm. Hitler feared he would lose in a direct confrontation with the Royal Navy, so the German surface fleet largely sat idle at anchor. Meanwhile, the U-boats and their all- volunteer crews were out at sea, hunting down enemy vessels. They sank the merchant vessels delivering the Allies’ much-needed materials of war, and even were able to achieve some success against much larger enemy warships. -

Maritime Patrol Aviation: 90 Years of Continuing Innovation

J. F. KEANE AND C. A. EASTERLING Maritime Patrol Aviation: 90 Years of Continuing Innovation John F. Keane and CAPT C. Alan Easterling, USN Since its beginnings in 1912, maritime patrol aviation has recognized the importance of long-range, persistent, and armed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in sup- port of operations afl oat and ashore. Throughout its history, it has demonstrated the fl ex- ibility to respond to changing threats, environments, and missions. The need for increased range and payload to counter submarine and surface threats would dictate aircraft opera- tional requirements as early as 1917. As maritime patrol transitioned from fl ying boats to land-based aircraft, both its mission set and areas of operation expanded, requiring further developments to accommodate advanced sensor and weapons systems. Tomorrow’s squad- rons will possess capabilities far beyond the imaginations of the early pioneers, but the mis- sion will remain essentially the same—to quench the battle force commander’s increasing demand for over-the-horizon situational awareness. INTRODUCTION In 1942, Rear Admiral J. S. McCain, as Com- plane. With their normal and advance bases strategically mander, Aircraft Scouting Forces, U.S. Fleet, stated the located, surprise contacts between major forces can hardly following: occur. In addition to receiving contact reports on enemy forces in these vital areas the patrol planes, due to their great Information is without doubt the most important service endurance, can shadow and track these forces, keeping the required by a fl eet commander. Accurate, complete and up fl eet commander informed of their every movement.1 to the minute knowledge of the position, strength and move- ment of enemy forces is very diffi cult to obtain under war Although prescient, Rear Admiral McCain was hardly conditions. -

Submarine Warfare, Fiction Or Reality? John Charles Cheska University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1962 Submarine warfare, fiction or reality? John Charles Cheska University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Cheska, John Charles, "Submarine warfare, fiction or reality?" (1962). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1392. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1392 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. bmbb ittmtL a zia a musv John C. Chaaka, Jr. A.B. Aaharat Collag* ThMis subnlttwi to tho Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of tha requlraaanta for tha degraa of Master of Arta Uoiwaity of Maaaaohuaetta Aaherat August, 1962 a 3, v TABU OF CONTENTS Hm ramp _, 4 CHAPTER I Command Structure and Policy 1 II Material III Operations 28 I? The Submarine War ae the Public Saw It V The Number of U-Boate Actually Sunk V VI Conclusion 69 APPENDXEJB APPENDIX 1 Admiralty Organisation in 1941 75 2 German 0-Boat 76 3 Effects of Strategic Bombing on Late Model 78 U-Boat Productions and Operations 4 U-Boats Sunk Off the United States Coaat 79 by United States Forces 5 U-Boats Sunk in Middle American Zone 80 inr United StatM ?bkii 6 U-Bosta Sunk Off South America 81 by United States Forces 7 U-Boats Sunk in the Atlantio in Area A 82 1 U-Boats Sunk in the Atlentio in Area B 84 9A U-Boats Sunk Off European Coast 87 by United States Forces 9B U-Bnata Sunk in Mediterranean Sea by United 87 States Forces TABLE OF CONTENTS klWDU p«g« 10 U-Boats Sunk by Strategic Bombing 38 by United States Amy Air Foreee 11 U-Boats Sunk by United States Forces in 90 Cooperation with other Nationalities 12 Bibliography 91 LIST OF MAPS AND GRAPHS MAP NO. -

Appendix A: Navy Activities Descriptions

Appendix A: Navy Activities Descriptions NORTHWEST TRAINING AND TESTING FINAL EIS/OEIS OCTOBER 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A NAVY ACTIVITIES DESCRIPTIONS .............................................................................. A-1 A.1 TRAINING ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................................. A-1 A.1.1 ANTI-AIR WARFARE TRAINING ............................................................................................................ A-1 A.1.1.1 Air Combat Maneuver ............................................................................................................... A-2 A.1.1.2 Missile Exercise (Air-to-Air) ....................................................................................................... A-3 A.1.1.3 Gunnery Exercise (Surface-to-Air) ............................................................................................. A-4 A.1.1.4 Missile Exercise (Surface-to-Air) ................................................................................................ A-5 A.1.2 ANTI-SURFACE WARFARE TRAINING ..................................................................................................... A-6 A.1.2.1 Gunnery Exercise Surface-to-Surface (Ship) .............................................................................. A-7 A.1.2.2 Missile Exercise Air-to-Surface .................................................................................................. A-8 A.1.2.3 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile -

4 Convoy Presentation Final V1.1

ALLIED CONVOY OPERATIONS IN THE BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC 1939-43 INTRODUCTION • History of Allied convoy operations IS the history of the Battle of the Atlantic • Scope of this effort: convoy operations along major transatlantic convoy routes • Detailed overview • Focus on role of Allied intelligence in the Battle of the Atlantic OUTLINE • Convoy Operations in the First Battle of the Atlantic, 1914-18 • Anglo-Canadian Convoy Operations, September 1939 – September 1941 • Enter The Americans: Allied Convoy Operations, September 1941 – Fall 1942 • The Allied Convoy System Fully Realized: Allied Convoy Operations, Fall 1942 – Summer 1943 THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC, 1914-18 • 1914-17: No convoy operations § All vessels sailed independently • Kaiserliche Marine use of U-boats primarily focused on starving Britain into submission § Prize rules • February 1915: “Unrestricted submarine warfare” § May 7, 1915 – RMS Lusitania u U-20 u 1,198 dead – 128 Americans • February 1917: unrestricted submarine warfare resumed § Directly led to US entry into WWI THE FIRST BATTLE OF THE ATLANTIC, 1914-18 • Unrestricted submarine warfare initially very effective § 25% of all shipping bound for Britain in March 1917 lost to U-boat attack • Transatlantic convoys instituted in May 1917 § Dramatically cut Allied losses • Post-war, Dönitz conceptualizes Rudeltaktik as countermeasure to convoys ANGLO-CANADIAN CONVOY OPERATIONS, SEPTEMBER 1939 – SEPTEMBER 1941 GERMAN U-BOAT FORCE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE WAR • On the outbreak of WWII, Hitler directed U-boat force -

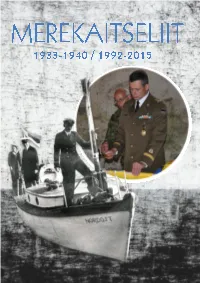

Merekaitseliit 1933-1940/1992-2015

MEREKAITSELIIT 1933–1940 / 1992–2015 Tallinn 2015 Väljaandja: Kaitseliit Koostaja: Tanel Lään Keelenõu: Piret Pääsuke Toimetaja: major Tanel Rütman Küljendus: Arielle Carroll Kaane kujundus: Erkki Pung Trükk: Hepter Grupp OÜ Esikaanel: Kaitseliidu Narva maleva „Nordost“ Merekaitseliidu 1937. a. sügisõppusel. Ringis: Kaitseliidu Saaremaa maleva pealik kolonelleitnant Kristjan Moora lööb naela Meremalevkonna lipu vardasse, tema selja taga kapten Jaen Teär 23. juunil 2014. Tagakaanel: Signalistid lähevad võistluspaika Narva-Jõesuus 1939. a. juu- nis. Õppetund mootoriklassis mereüksuste pealikute kursusel 1938. aastal. Veeteede Ameti hüdrograafialaev ja AS PKL vedurlaev „Helmut Kanter“ 2006. a. võidupühal Küdema lahel ISBN 978-9949-9443-1-6 Eessõna Hea Lugeja! Sa hoiad käes raamatut, mis püüab linnulennult anda ülevaate Kaitseliidu meren- dusalasest tegevusest läbi aegade. Algmaterjalina on käesoleva väljaande esimeses osas kasutatud lisaks vähestele arhiivimaterjalidele kirjandust, mälestusi, intervjuusid ja Kaitseliidu ajakirja Kaitse Kodu! ning malevate Teated 1930-1940. aastate numbreid. Viimastes aval- datud käskkirjad ja erinevad protokollid võimaldavad taastada suhteliselt täpselt Merekaitseliidu tolleaegse kronoloogia. Olukirjeldusi õppustest ja tegemistest leidub aga ajakirjas Kaitse Kodu!. Käesolev kogumik annab hea ajaloolise ülevaate Eestis rannikukaitse arendami- seks tehtud ettepanekutest ja otsustest aastatel 1930-1940. Võrdlusena saa- me ülevaate ka sellest, mida me pärast taasiseseisvumist oleme samas valdkonnas tänaseks -

Issue 5 Alumni & Affiliates Newsletter

Manchester & Salford Universities Royal Naval Unit M&S URNU Issue 5 Alumni & Affiliates Newsletter Message from the Boss Issue 5 I can hardly believe it’s been contractors and our own to find our sea legs again and July 2013 six months since I last took engineers have delivered the visit some of our most loved the opportunity to write in this most up to date and capable ports whilst again achieving newsletter but in the I P2000 in the Royal Navy. the URNU Mission Statement. ntervening period, the unit Despite a lack of ship, the We will again return to a busy has been extremely busy and unit and it’ members have in autumn programme of has gone through immense no way been idle and this time recruiting and inducting new change. The greatest chal- has allowed us to strengthen members. The annual HMS BITER lenge of recent months has our links with the wider armed Trafalgar night dinner and a BFPO 229 undoubtedly been the forces. As you will read later hectic series of Sea Training M&S URNU extended maintenance period in this newsletter, members weekends. The busy University Barracks and re-engineering of HMS have travelled the length and academic term will culminate Boundary Lane MANCHESTER BITER. What began as a breadth of the world, on a in the Re-dedication of HMS M15 6DH simple 8 week overhaul and plethora of RN ships and BITER. This will be a huge engine replacement quickly yachts and we are all a little event, held at the Imperial T: 0161 237 3308 developed into a major fitter for the amount of sport War Museum North when we [email protected] project. -

Ministry of Defence Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym Long Title 1ACC No. 1 Air Control Centre 1SL First Sea Lord 200D Second OOD 200W Second 00W 2C Second Customer 2C (CL) Second Customer (Core Leadership) 2C (PM) Second Customer (Pivotal Management) 2CMG Customer 2 Management Group 2IC Second in Command 2Lt Second Lieutenant 2nd PUS Second Permanent Under Secretary of State 2SL Second Sea Lord 2SL/CNH Second Sea Lord Commander in Chief Naval Home Command 3GL Third Generation Language 3IC Third in Command 3PL Third Party Logistics 3PN Third Party Nationals 4C Co‐operation Co‐ordination Communication Control 4GL Fourth Generation Language A&A Alteration & Addition A&A Approval and Authorisation A&AEW Avionics And Air Electronic Warfare A&E Assurance and Evaluations A&ER Ammunition and Explosives Regulations A&F Assessment and Feedback A&RP Activity & Resource Planning A&SD Arms and Service Director A/AS Advanced/Advanced Supplementary A/D conv Analogue/ Digital Conversion A/G Air‐to‐Ground A/G/A Air Ground Air A/R As Required A/S Anti‐Submarine A/S or AS Anti Submarine A/WST Avionic/Weapons, Systems Trainer A3*G Acquisition 3‐Star Group A3I Accelerated Architecture Acquisition Initiative A3P Advanced Avionics Architectures and Packaging AA Acceptance Authority AA Active Adjunct AA Administering Authority AA Administrative Assistant AA Air Adviser AA Air Attache AA Air‐to‐Air AA Alternative Assumption AA Anti‐Aircraft AA Application Administrator AA Area Administrator AA Australian Army AAA Anti‐Aircraft Artillery AAA Automatic Anti‐Aircraft AAAD Airborne Anti‐Armour Defence Acronym -

BRIEF HISTORY of HMCS AMHERST the “Flower” Class

BRIEF HISTORY OF HMCS AMHERST The “Flower” Class corvette, HMCS AMHERST, pennant number K-148, was the first of three ships of the same class completed by the Saint John Drydock and Shipbuilding Co. Ltd.1 Laid down on 25 May 1940, she was launched on 4 December the same year, Mrs. Frederick F. Mathers, wife of the Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, sponsoring the ship.2 HMCS AMHERST may be justly called a “fighting ship.” Built quickly in a time of emergency, when ships were scare and the need great, she lived fully in a time of war and, with the coming of peace, vanished. Her’s was a lifetime of fire and peril when, it can be quite truthfully said, she did not know for months on end when the torpedoes which ended the lives of the merchant ships she shepherded and sometimes those of her mates, would come out of the dark night and destroy her too. Endurance trials for the corvette were held in July 1941 and acceptance trials on the 4th of the following month. On 5 August 1941, HMCS AMHERST was commissioned with Lieutenant-Commander A. K. Young, RCNR, as her first Commanding Officer.3 The ship was named after Amherst, the shire town of Cumberland County, Nova Scotia. Earlier, this town had been called Les Planches by the French, but was given its present name in 1759 in honour of General Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of the forces in North America and, a year later, Governor-General of British North America. Even before she was commissioned, AMHERST became a special charge of the War Workers of the Toronto Evening Telegram. -

Introduction to Sonar, Naval Education and Training Command. Revised Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 129 585 SE 021 157 TITLE Introduction to Sonar, Naval Education and Irainin(; Command. Revised Edition. INSTITUTION Naval Education and Training Command, Pensacola, Fla. REPORT NO NAVEDTRA-10130-C PUB DATE 76 NOTE 223p.; Photographs and shaded figures may not reproduce well AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Stock Number 0502-LP-050-6510; No price quoted) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$12.71 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acoustics; *Inservice Education; *InLicructional Ni..terials; *Marine Technicians; Military Personnel; Military Training; *Physics; Science Education; *Technical Education; Textbooks IDENTIFIERS *Navy; *Sonar ABSTRACT This Rate Training Manual (FTM) and Nonresident Career Course form a self-study package for those U.S. Navy personnel who are seeking advancement in the Sonar Technician Rating. Among the requirements of the rating are the abilities to obtain and interpret underwater data, operate and maintain upkeep of sonar equipment, and interpret target and oceonographic data. Designed for individual study and not formal classroom instruction, this book provides subject matter that relates directly to the occupational qualifications of the Sonar Technician Rating. Included in the book are chapters on the physics of sound, the bathythermograph, principles of sonar, basic fire control, test equipment and methods, and security. (Author/MH) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished *materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort* *to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal *reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality *of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available *via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). -

Avenger Class Escort Carrier

28 - Avenger Class EC Version 5 1 Avenger Class Escort Carrier [1] [2] [3] Commissioned Ships of class Ships lost HMS Avenger2 Mar 42 15 Nov 1942 (U 155 west of Gibraltar) HMS Biter May 42 HMS Dasher Jul 42 27 Mar 1943 (Internal explosion in the Clyde Estuary) HMS Charger3 Mar 42 HMS Dasher [4] 1 Lend lease vessels built in US and converted from merchantmen whilst still in build. US classification was BAVG and it was a modified US Long Island Class. 2 Avenger had no Island. 3 Retained in US and used for training of USN and FAA personnel. 1 28 - Avenger Class EC Version 5 HMS Dasher [4] HMS Dasher [4] Sea Hurricane Mk 1b, on lift of HMS Avenger, Sept 1942 [5] 2 28 - Avenger Class EC Version 5 HULL DATA Length (pp) Length (oa) 150.04 m [6] Beam 20.35 m [6] Full load displacement 9,144 tonne [1] Propulsion Machinery 4 x Diesel engines [6]4 1 shaft [6] 16.5 knots [6] 8,500 SHP [6] Complement 555 [6] 56 Aircraft 15 [6] ARMAMENT DATA Main Armament [6] 3 x 4 inch Single mountings [7]. 2 fwd and 1 aft. Secondary Armament [6] 15 x 20 mm 4 x twin mounting 7 x single mounting [7] 4” outload [8, p. C5] 330 rpg 990 20 mm outload 15,000 estimated Depth Charge [9, pp. a1-3] Mk II* 104 Torpedo outload [10, pp. 13, Oct 44] 18 inch 14 Demolition Charges [11, p. 95] Block TNT 1¼ lb 100 7 Bombs [12, p. -

Canadian Innovations in Naval Acoustics from World War II to 1967

CAN UNCLASSIFIED Canadian Innovations in Naval Acoustics from World War II to 1967 Cristina D. S. Tollefsen DRDC – Atlantic Research Centre Acoustics Today Volume number: 14 Issue number: 2 Pagination info: 25–33 Date of Publication from Ext Publisher: June 2018 Defence Research and Development Canada External Literature (P) DRDC-RDDC-2018-P094 July 2018 CAN UNCLASSIFIED CAN UNCLASSIFIED IMPORTANT INFORMATIVE STATEMENTS This document was reviewed for Controlled Goods by Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC) using the Schedule to the Defence Production Act. Disclaimer: This document is not published by the Editorial Office of Defence Research and Development Canada, an agency of the Department of National Defence of Canada but is to be catalogued in the Canadian Defence Information System (CANDIS), the national repository for Defence S&T documents. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (Department of National Defence) makes no representations or warranties, expressed or implied, of any kind whatsoever, and assumes no liability for the accuracy, reliability, completeness, currency or usefulness of any information, product, process or material included in this document. Nothing in this document should be interpreted as an endorsement for the specific use of any tool, technique or process examined in it. Any reliance on, or use of, any information, product, process or material included in this document is at the sole risk of the person so using it or relying on it. Canada does not assume any liability in respect of any damages or losses arising out of or in connection with the use of, or reliance on, any information, product, process or material included in this document.