Thrushes Wildlife Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swainson's Thrush

Swainson’s Thrush Catharus ustulatus Account #: 8365 Species code: SWTH Band size: 1B Skull: 1 Nov (Small windows may remain indefinitely) Pyle: p397 Moult timing Sibley: p407 Moult Formative Definitive Basic 10 primaries (10th reduced) 9 secondaries 12 tail feathers Juvenile plumage is distinctive. Formative and basic plumages are very similar. The absence of moult limits is not easily discerned. Ageing Use moult limits to separate formative plumage from basic plumage. Tail shape may be reliable in some cases, but intermediates occur. P10 length may also be useful. Moult limit Formative Basic Juvenile feathers among the great- er coverts typically have buffy tips. Spots are generally larger on the innermost feathers. Spots become more subtle and may disappear when feathers are worn. Tail Shape Juvenile/Formative Basic The angle of the feather tip differs. Formative = 88° angle Basic = 109° angle Worn feathers may be misleading. Sexing Juvenile Formative Basic No known plumage methods. During the breeding season cloacal protuberance and brood patch are well developed. References: Collier & Wallace 1989, MacGill Bird Observatory, Morris & Bradley 2000, Pyle 1997, Tabular Pyle 2007. Images: David Hodkinson. Compiled by David Hodkinson, 12 December 2011; North American edition General editor: David Hodkinson - [email protected] 8365 Identification Similar species: Hermit Thrush, Grey-cheeked Thrush, Bicknell’s Thrush & Veery. Hermit Thrush Swainson’s Thrush P6 emargination P9 P9 Swainson’s - No emargination Hermit - Emarginated Grey-cheeked - Often emarginated Veery - Slight emargination P6 P6 Wing Formula Hermit: P9 < P6, Swainson’s, Grey-cheeked & Veery: P9 > P6 Hermit Thrush Swainson’s Thrush Back vs Tail colour Swainson’s - No contrast Hermit - Tail colour contrasts with back colour. -

Hermit Thrush (<Em>Catharus Guttatus</Em>) and Veery (<Em>C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2010 Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus) and Veery (C. fuscescens) Breeding Habitat Associations in Southern Appalachian High-Elevation Forests. Andrew J. Laughlin East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Laughlin, Andrew J., "Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus) and Veery (C. fuscescens) Breeding Habitat Associations in Southern Appalachian High-Elevation Forests." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1695. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1695 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus) and Veery (C. fuscescens) Breeding Habitat Associations in Southern Appalachian High-Elevation Forests __________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Biological Sciences East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree Masters of Science in Biological Sciences _________________ by Andrew J. Laughlin May 2010 __________________ Dr. Fred J. Alsop III, Chair Dr. Istvan Karsai Dr. Thomas F. Laughlin Keywords: Birds, Habitat Partitioning, Principal Components Analysis ABSTRACT Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus) and Veery (C. fuscescens) Breeding Habitat Associations in Southern Appalachian High-Elevation Forests by Andrew J. Laughlin The Hermit Thrush is a new breeding bird in the Southern Appalachian high-elevation mountains, having expanded its range southward over the last few decades. -

Understanding the Importance of Color Matching Coding the Colors

When red is not red: Understanding the importance of color matching Color as brand Color is an integral part of branding. Whether it’s the robin’s egg blue box with jewelry inside, a green and yellow tractor or the white delivery truck with a purple and orange logo, we instinctively know brands by their colors. As a commercial printer, we understand that achieving accurate and consistent color results in everything we produce is vital in protecting the integrity of your brand. Color Color vs. perception reality Color perception is the way your eye Color reality is the scientific means of sees the color. Many factors can affect it matching a color. We have — the lighting, the environment, the type spectrophotometers that measure any of printer being used (toner-based or color visible to the human eye. inkjet), and even the eye of the beholder! We don’t all see color the same way. Color perception Color reality Lighting Environment Spectrophotometers Printer Your Eye Simply put, the red you see may not be the red you wanted. To match colors, we examine the color we want to achieve against the color we’ve printed to see how close they actually are. Our color management team works to get your color correct every time. Coding CMYK, which stands for “Cyan Magenta Yellow Black,” is primarily concerned with the combination of ink on the paper to produce the colors colors—in particular, the four basic colors used for printing color images. We combine these four colors on a substrate (the underlying surface), which is essentially the fifth color. -

Catharus Fuscescens the Veery, Like Most Woodland Thrushes, Is More

Veery Catharus fuscescens The Veery, like most woodland thrushes, is more frequently heard than seen. Most bird ers are familiar with its veer alarm call. Its melodious song, a series of downward spiraling notes, rivals that of the Hermit Thrush. Veeries breed throughout Vermont; their range of accepted habitats overlaps that of all other thrushes except the Gray cheeked. Although accepting a nearly ubiq uitous array of breeding areas, in Connecti cut Veeries preferred moist sites (Berlin 1977) and, indeed, few swamps or moist son's thrushes in overlapping territories woodlands in the Northeast are unoccupied (D. P. Kibbe, pers. observ.). by Veeries. However, Vermont's greatest re The Veery's bulky nest is built on a thick corded breeding densities for the Veery-64 foundation of dead leaves, usually among to 91 pairs per 100 ha (26 to 37 pairs per saplings or in shrubbery on or near the lOa a)-have been found in habitat com ground. Three to 5 pale blue eggs are laid; posed of mixed forest and old fields in cen they are incubated for II to 12 days. Twenty tral Vermont (Nicholson 1973, 1975, 1978). three Vermont egg dates range from May 26 Dilger (195 6a) found that Veeries preferred to July 23, with a peak in early June. Nest disturbed (cutover) forests, presumably lings grow rapidly, and they may leave the because of dense undergrowth there. The nest in as few as 10 days. Nestlings have Veery's acceptance of varied habitat is not been found as early as June 10 and as late surprising in light of its geographic distri as July 6. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Conservation Assessment for Swainson's Thrush (Catharus

Conservation Assessment for Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) Photo: Maria Bajema USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region May 10, 2004 Tony Rinaldi Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Mike Worland Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on the Swainson’s Thrush and provides information to serve as a Conservation Assessment for the Eastern Region of the Forest Service. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the Swainson’s Thrush, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service - Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 580 Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.....................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................5 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY...............................................5 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES................................................................5 LIFE HISTORY......................................................................................6 Reproduction..........................................................................................6 -

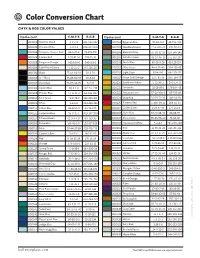

Color Conversion Chart

Color Conversion Chart CMYK & RGB COLOR VALUES Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B Opalescent C-M-Y-K R-G-B 000009 Reactive Cloud 4-2-1-0 241-243-247 000164 Egyptian Blue 81-48-0-0 49-116-184 000013 Opaque White 4-2-2-1 246-247-249 000203 Woodland Brown 22-63-87-49 120-70-29 000016 Turquoise Opaque Rod 65-4-27-6 75-174-179 000206 Elephant Gray 35-30-32-18 150-145-142 000024 Tomato Red 1-99-81-16 198-15-36 000207 Celadon Green 43-14-46-13 141-167-137 000025 Tangerine Orange 1-63-100-0 240-119-2 000208 Dusty Blue 60-25-9-28 83-123-154 000034 Light Peach Cream 5-12-15-0 243-226-213 000212 Olive Green 44-4-91-40 104-133-42 000100 Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000216 Light Cyan 62-4-9-0 88-190-221 000101 Stiff Black 75-66-60-91 10-9-10 000217 Green Gold Stringer 11-6-83-13 206-194-55 000102 Blue Black 76-69-64-85 6-7-13 000220 Sunflower Yellow 5-33-99-1 240-174-0 000104 Glacier Blue 38-3-5-0 162-211-235 000221 Citronelle 35-15-95-1 179-184-43 000108 Powder Blue 41-15-11-3 153-186-207 000222 Avocado Green 57-24-100-2 125-155-48 000112 Mint Green 43-2-49-2 155-201-152 000224 Deep Red 16-99-73-38 140-24-38 000113 White 5-2-5-0 244-245-241 000225 Pimento Red 1-100-99-11 208-10-13 000114 Cobalt Blue 86-61-0-0 43-96-170 000227 Golden Green 2-24-97-34 177-141-0 000116 Turquoise Blue 56-0-21-1 109-197-203 000236 Slate Gray 57-47-38-40 86-88-97 000117 Mineral Green 62-9-64-27 80-139-96 000241 Moss Green 66-45-98-40 73-84-36 000118 Periwinkle 66-46-1-0 102-127-188 000243 Translucent White 5-4-4-1 241-240-240 000119 Mink 37-44-37-28 132-113-113 000301 Pink 13-75-22-10 -

Luscinia Luscinia)

Ornis Hungarica 2018. 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia) Tibor CSÖRGO˝ 1 , Péter FEHÉRVÁRI2, Zsolt KARCZA3, Péter ÓCSAI4 & Andrea HARNOS2* Received: April 20, 2018 – Revised: May 10, 2018 – Accepted: May 20, 2018 Tibor Csörgo,˝ Péter Fehérvári, Zsolt Karcza, Péter Ócsai & Andrea Harnos 2018. Exploratory analyses of migration timing and morphometrics of the Thrush Nightingale (Luscinia luscinia). – Ornis Hungarica 26(1): 149–170. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0010 Abstract Ornithological studies often rely on long-term bird ringing data sets as sources of information. However, basic descriptive statistics of raw data are rarely provided. In order to fill this gap, here we present the seventh item of a series of exploratory analyses of migration timing and body size measurements of the most frequent Passerine species at a ringing station located in Central Hungary (1984–2017). First, we give a concise description of foreign ring recoveries of the Thrush Nightingale in relation to Hungary. We then shift focus to data of 1138 ringed and 547 recaptured individuals with 1557 recaptures (several years recaptures in 76 individuals) derived from the ringing station, where birds have been trapped, handled and ringed with standardized methodology since 1984. Timing is described through annual and daily capture and recapture frequencies and their descriptive statistics. We show annual mean arrival dates within the study period and present the cumulative distributions of first captures with stopover durations. We present the distributions of wing, third primary, tail length and body mass, and the annual means of these variables. -

Bird Species Checklist

6 7 8 1 COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi COMMON NAME Sp Su Fa Wi Bank Swallow R White-throated Sparrow R R R Bird Species Barn Swallow C C U O Vesper Sparrow O O Cliff Swallow R R R Savannah Sparrow C C U Song Sparrow C C C C Checklist Chickadees, Nuthataches, Wrens Lincoln’s Sparrow R U R Black-capped Chickadee C C C C Swamp Sparrow O O O Chestnut-backed Chickadee O O O Spotted Towhee C C C C Bushtit C C C C Black-headed Grosbeak C C R Red-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Lazuli Bunting C C R White-breasted Nuthatch U U U U Blackbirds, Meadowlarks, Orioles Brown Creeper U U U U Yellow-headed Blackbird R R O House Wren U U R Western Meadowlark R O R Pacific Wren R R R Bullock’s Oriole U U Marsh Wren R R R U Red-winged Blackbird C C U U Bewick’s Wren C C C C Brown-headed Cowbird C C O Kinglets, Thrushes, Brewer’s Blackbird R R R R Starlings, Waxwings Finches, Old World Sparrows Golden-crowned Kinglet R R R Evening Grosbeak R R R Ruby-crowned Kinglet U R U Common Yellowthroat House Finch C C C C Photo by Dan Pancamo, Wikimedia Commons Western Bluebird O O O Purple Finch U U O R Swainson’s Thrush U C U Red Crossbill O O O O Hermit Thrush R R To Coast Jackson Bottom is 6 Miles South of Exit 57. -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Systematics of Zoothera Thrushes, and a Synthesis of True Thrush Molecular Systematic Relationships

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 49 (2008) 377–381 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Short Communication Systematics of Zoothera thrushes, and a synthesis of true thrush molecular systematic relationships Gary Voelker a,*, John Klicka b a Department of Biology, University of Memphis, 3700 Walker Avenue, Memphis, TN 38152, USA b Barrick Museum of Natural History, Box 454012, University of Nevada Las Vegas, 4504 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, NV 89154-4012, USA 1. Introduction Questions regarding inter-specific relationships remain within both Catharus and Myadestes. At the inter-generic level, Klicka The true thrushes (Turdinae; Sibley and Monroe, 1990) are a et al. (2005) conducted analyses of true thrush relationships, using speciose lineage of songbirds, with a near-cosmopolitan distribu- the Sialia–Myadestes–Neocossyphus clade (hereafter referred to as tion. Following the systematic placement of true thrushes as a the ‘‘Sialia clade”) as the outgroup. While clearly a true thrush line- close relative of Old World flycatchers and chats (Muscicapinae) age, the Sialia clade is very divergent from other true thrush lin- by the DNA–DNA hybridization work of Sibley and Ahlquist eages. Homoplasy caused by the use of this divergent clade as a (1990), a number of molecular systematic studies have focused root could explain at least some of the as yet unresolved inter-gen- on various aspects of true thrush relationships. These studies have eric relationships within true thrushes. included phylogenetic assessments of genera membership in true Our main objective in this study is to use dense taxon sampling thrushes, assessments of relationships among and within true across true thrushes to resolve inter- and intra-generic relation- thrush genera, and the recognition of ‘‘new” species (Bowie et al., ships that remain unclear.