Fhlbiamendcomplrescissiond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JP Morgan Chase Sofya Frantslikh Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 3-14-2005 Mergers and Acquisitions, Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase Sofya Frantslikh Pace University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Corporate Finance Commons Recommended Citation Frantslikh, Sofya, "Mergers and Acquisitions, Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase" (2005). Honors College Theses. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thesis Mergers and Acquisitions Featured Case Study: JP Morgan Chase By: Sofya Frantslikh 1 Dedicated to: My grandmother, who made it her life time calling to educate people and in this way, make their world better, and especially mine. 2 Table of Contents 1) Abstract . .p.4 2) Introduction . .p.5 3) Mergers and Acquisitions Overview . p.6 4) Case In Point: JP Morgan Chase . .p.24 5) Conclusion . .p.40 6) Appendix (graphs, stats, etc.) . .p.43 7) References . .p.71 8) Annual Reports for 2002, 2003 of JP Morgan Chase* *The annual reports can be found at http://www.shareholder.com/jpmorganchase/annual.cfm) 3 Abstract Mergers and acquisitions have become the most frequently used methods of growth for companies in the twenty first century. They present a company with a potentially larger market share and open it u p to a more diversified market. A merger is considered to be successful, if it increases the acquiring firm’s value; m ost mergers have actually been known to benefit both competition and consumers by allowing firms to operate more efficiently. -

Global Payments, Inc. (GPN) J.P

Corrected Transcript 14-Nov-2017 Global Payments, Inc. (GPN) J.P. Morgan Ultimate Services Investor Conference Total Pages: 18 1-877-FACTSET www.callstreet.com Copyright © 2001-2017 FactSet CallStreet, LLC Global Payments, Inc. (GPN) Corrected Transcript J.P. Morgan Ultimate Services Investor Conference 14-Nov-2017 CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Tien-Tsin Huang Analyst, JPMorgan Securities LLC Jeffrey Steven Sloan Chief Executive Officer & Director, Global Payments, Inc. ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION SECTION Tien-Tsin Huang Analyst, JPMorgan Securities LLC Thanks, everybody for joining. My name is Tien-Tsin Huang; cover the Payments and IT Services Group at JPMorgan and super-excited and delighted to have Jeff Sloan back with us, CEO of Global Payments, [indiscernible] (00:14) always busy – we respect having him here again. So thank you. So what we'll do is, we'll have Q&A, I'll field it as I always do. I took a lot of questions from you guys and pieced it together. We'll go through some of these and then we'll open it up for Q&A. ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... QUESTION AND ANSWER SECTION Tien-Tsin -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION MARGARITA VILLAGRAN, § § Plaintiff, §

Case 4:05-cv-02685 Document 75 Filed in TXSD on 10/23/07 Page 1 of 43 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION MARGARITA VILLAGRAN, § § Plaintiff, § v. § CIVIL ACTION NO. H-05-2685 § CENTRAL FORD, INC., § § Defendant. § MEMORANDUM AND OPINION Margarita Villagran sues on her own behalf and on behalf of a class of people sent mailings by Central Ford, Inc., an automobile dealership. Villagran alleges that the mailings violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), 15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq., because they used information obtained without authorization from the addressees’ credit reports, for a purpose not permitted under the Act. The FCRA allows companies such as Central Ford to use information obtained from consumers’ credit reports for communications that extend “firm offers of credit.” The FCRA prohibits the use of such information to advertise rather than extend “firm offers of credit.” Villagran alleges that the mailing she and others received did not extend a “firm offer of credit.” She seeks damages under 15 U.S.C. § 1681n(a), which provides that for each violation, the consumer may recover “any actual damages sustained by the consumer as a result of [a violation] or damages of not less than $100 and not more than $1,000,” punitive damages, attorney’s fees, and costs. Villagran has amended her motion to certify a class action, (Docket Entry No. 55); Case 4:05-cv-02685 Document 75 Filed in TXSD on 10/23/07 Page 2 of 43 Central Ford has responded, (Docket Entry No. -

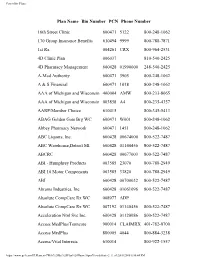

Powerline Plans

Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number 16th Street Clinic 600471 5122 800-248-1062 170 Group Insurance Benefits 610494 9999 800-788-7871 1st Rx 004261 CRX 800-964-2531 4D Clinic Plan 006037 810-540-2425 4D Pharmacy Management 600428 01990000 248-540-2425 A-Med Authority 600471 3905 800-248-1062 A & S Financial 600471 1018 800-248-1062 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 400004 AMW 800-233-8065 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 003858 A4 800-235-4357 AARP/Member Choice 610415 800-345-5413 ABAG Golden Gate Brg WC 600471 W001 800-248-1062 Abbey Pharmacy Network 600471 1451 800-248-1062 ABC Liquors, Inc. 600428 00674000 800-522-7487 ABC Warehouse,Detroit MI 600428 01140456 800-522-7487 ABCRC 600428 00677003 800-522-7487 ABI - Humphrey Products 003585 23070 800-788-2949 ABI 10 Motor Components 003585 33820 800-788-2949 ABI 600428 00700032 800-522-7487 Abrams Industries, Inc. 600428 01061096 800-522-7487 Absolute CompCare Rx WC 008977 ADP Absolute CompCare Rx WC 007192 01140456 800-522-7487 Acceleration Ntnl Svc Inc. 600428 01120086 800-522-7487 Access MedPlus/Tenncare 900014 CLAIMRX 401-782-0700 Access MedPlus 880005 4044 800-884-3238 Access/Vital Interests 610014 800-922-1557 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (1 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Accident Fund of Michigan 600428 00700054 800-522-7487 Accubank Mortgage Inc 600428 00672018 800-522-7487 Aclaim 005848 800-422-5246 ACMG Employers Health Plan 400004 ACM 800-233-8065 Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (2 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 ACT Industries, Inc. -

List of Participating Merchants Mastercard Automatic Billing Updater

List of Participating Merchants MasterCard Automatic Billing Updater 3801 Agoura Fitness 1835-180 MAIN STREET SUIT 247 Sports 5378 FAMILY FITNESS FREE 1870 AF Gilroy 2570 AF MAPLEWOOD SIMARD LIMITED 1881 AF Morgan Hill 2576 FITNESS PREMIER Mant (BISL) AUTO & GEN REC 190-Sovereign Society 2596 Fitness Premier Beec 794 FAMILY FITNESS N M 1931 AF Little Canada 2597 FITNESS PREMIER BOUR 5623 AF Purcellville 1935 POWERHOUSE FITNESS 2621 AF INDIANAPOLIS 1 BLOC LLC 195-Boom & Bust 2635 FAST FITNESS BOOTCAM 1&1 INTERNET INC 197-Strategic Investment 2697 Family Fitness Holla 1&1 Internet limited 1981 AF Stillwater 2700 Phoenix Performance 100K Portfolio 2 Buck TV 2706 AF POOLER GEORGIA 1106 NSFit Chico 2 Buck TV Internet 2707 AF WHITEMARSH ISLAND 121 LIMITED 2 Min Miracle 2709 AF 50 BERWICK BLVD 123 MONEY LIMITED 2009 Family Fitness Spart 2711 FAST FIT BOOTCAMP ED 123HJEMMESIDE APS 2010 Family Fitness Plain 2834 FITNESS PREMIER LOWE 125-Bonner & Partners Fam 2-10 HBW WARRANTY OF CALI 2864 ECLIPSE FITNESS 1288 SlimSpa Diet 2-10 HOLDCO, INC. 2865 Family Fitness Stand 141 The Open Gym 2-10 HOME BUYERS WARRRANT 2CHECKOUT.COM 142B kit merchant 21ST CENTURY INS&FINANCE 300-Oxford Club 147 AF Mendota 2348 AF Alexandria 3012 AF NICHOLASVILLE 1486 Push 2 Crossfit 2369 Olympus 365 3026 Family Fitness Alpin 1496 CKO KICKBOXING 2382 Sequence Fitness PCB 303-Wall Street Daily 1535 KFIT BOOTCAMP 2389730 ONTARIO INC 3045 AF GALLATIN 1539 Family Fitness Norto 2390 Family Fitness Apple 304-Money Map Press 1540 Family Fitness Plain 24 Assistance CAN/US 3171 AF -

Actions of the Board, Its Staff, and the Federal Reserve Banks; Applications and Reports Received

Federal Reserve Release H.2 Actions of the Board, Its Staff, and the Federal Reserve Banks; Applications and Reports Received No. 45 Week Ending November 7, 1998 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC 20551 H.2 Board Actions November 1, 1998 to November 7, 1998 Bank Holding Companies Banc One Corporation, Columbus, Ohio -- requests by certain commenters for reconsideration of the Board's approval of the application to merge with First Chicago NBD Corporation, Chicago, Illinois. - Denied, November 2, 1998 Peoples Heritage Financial Group, Inc., Portland, Maine, and Peoples Heritage Merger Corp. -- to merge with SIS Bancorp, Inc., Springfield, Massachusetts, and acquire Springfield Institution for Savings and Glastonbury Bank & Trust Company, Glastonbury, Connecticut. - Approved, November 4, 1998 Banks, State Member Marine Midland Bank, Buffalo, New York -- request for an exemption from section 23A of the Federal Reserve Act to acquire the commercial loan portfolio of the New York City and Chicago branches and related Cayman Island branch and International Banking facility of Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, Ltd., Victoria, Hong Kong. - Granted, November 3, 1998 Currency Federal Reserve notes -- 1999 new currency budget. - Approved, November 4, 1998 Regulations And Policies To Their Credit: Women-Owned Businesses -- availability of a videotape designed to heighten awareness among lenders about the business opportunities available in lending to businesses owned by women. - Announced, November 2, 1998 Reserve -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

1 THE HONORABLE CATHERINE SHAFFER 2 3 4 5 6 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF WASHINGTON IN AND FOR KING COUNTY 8 FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK OF ) CHICAGO, ) 9 ) Case No. 10-2-36526-5 SEA 10 Plaintiff, ) ) AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR 11 v. ) RESCISSION AND DAMAGES ) 12 BANC OF AMERICA SECURITIES LLC; ) 13 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC; ) GOLDMAN, SACHS & CO.; RBS ) 14 SECURITIES INC. f/k/a GREENWICH ) CAPITAL MARKETS, INC.; MERRILL ) 15 LYNCH, PIERCE, FENNER & SMITH ) INCORPORATED; LONG BEACH ) 16 SECURITIES CORP.; WAMU ASSET ) 17 ACCEPTANCE CORP.; WAMU CAPITAL ) CORP.; and JOHN DOE DEFENDANTS, 1- ) 18 50, ) ) 19 Defendants. ) ) 20 ) 21 ) 22 23 24 25 26 LAW OFFICES OF KELLER ROHRBACK L .L .P. 1201 THIRD AVENUE, SUITE 3200 AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR RESCISSION AND DAMAGES SEATTLE, WASHINGTON 98101-3052 TELEPHONE: (206) 623-1900 FACSIMILE: (206) 623-3384 1 Table of Contents 2 I. NATURE OF THE ACTION............................................................................................1 3 4 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE........................................................................................8 5 III. THE PARTIES................................................................................................................10 6 A. Plaintiff................................................................................................................10 7 B. Defendants...........................................................................................................12 8 C. The John Doe Defendants ...................................................................................17 -

BANK UNITED of TEXAS FSB V. US CONCLUSION For

BANK UNITED OF TEXAS FSB v. U.S. 645 Cite as 50 Fed.Cl. 645 (2001) CONCLUSION to damages of $8,826,783 for the proven For the foregoing reasons, the court finds costs incurred to mitigate the breach. that plaintiffs have not met the requirements So ordered. for class certification as set forth in RCFC 23 and Quinault. Plaintiffs have not demon- strated that certification in this action will United States O74(13, 15) serve the interests of justice or is otherwise Plaintiffs who prevailed in liability phase appropriate.10 Therefore, the court DE- of Winstar action were not entitled to recov- NIES plaintiffs’ September 21, 1999 motion ery of lost profits from the contract breach, for class certification. since they could and did mitigate the signifi- cant loss of borrowing capacity caused by the IT IS SO ORDERED. passage of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA); rather, plaintiffs were entitled to damages of , $8,826,783 for the proven costs incurred to mitigate the breach. Federal Deposit Insur- ance Act, § 2[1] et seq., 12 U.S.C.A. § 1811 et seq. BANK UNITED OF TEXAS FSB, USAT Walter B. Stuart, IV, Houston, TX, for Holdings Inc., Hyperion Holdings Inc. plaintiffs. David T. Hedges, Jr., John D. and Hyperion Partners L.P., Plaintiffs, Taurman, Karen Jewell, James A. Reeder, v. Jr., Tegan Flynn, Joseph E. Hunsader, Fred Williams and Michael Holmes, of counsel. UNITED STATES of America, Defendant. John J. Hoffman, with whom were Acting No. 95–473 C. Assistant Attorney General David W. Ogden, David M. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 199 / Monday, October 16, 1995 / Notices 53611

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 199 / Monday, October 16, 1995 / Notices 53611 (``the Stafford Act''). I, therefore, declare that (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance No. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Notice is such a disaster exists in the State of Florida. 83.516, Disaster Assistance) hereby given that, in a letter dated You are authorized to coordinate all James L. Witt, September 29, 1995, the President disaster relief efforts which have the purpose Director. amended the cost-sharing arrangements of alleviating the hardship and suffering [FR Doc. 95±25574 Filed 10±13±95; 8:45 am] concerning Federal funds provided caused by the disaster on the local BILLING CODE 6718±02±P under the authority of the Robert T. population, and to provide appropriate Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency assistance for required emergency measures, Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 51521 et seq.), authorized under Title IV of the Stafford Act, [FEMA±1069±DR] in a letter to James L. Witt, Director of to save lives, protect property and public the Federal Emergency Management health and safety, and lessen or avert the Florida; Amendment to Notice of a threat of a catastrophe in the designated Major Disaster Declaration Agency, as follows: areas. Specifically, you are authorized to I have determined that the damage in the identify, mobilize, and provide at your AGENCY: Federal Emergency U.S. Virgin Islands, resulting from Hurricane discretion, equipment and resources Management Agency (FEMA). Marilyn on September 15±17, 1995, is of necessary to alleviate the impacts of the ACTION: Notice. sufficient severity and magnitude that special disaster. I have further authorized direct cost-sharing conditions are warranted under Federal assistance for the first 72 hours at SUMMARY: This notice amends the notice the Robert T. -

No. 541 Expert Report of Daniel R. Fischel

FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 03/14/2013 INDEX NO. 651786/2011 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 541 CONFIDENTIAL RECEIVED NYSCEF: 03/14/2013 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEWYORK COUNTY OF NEWYORK __________________________________________ ) In the matter of the application of ) Index No. 651786/2011 THE BANK OF NEW YORK MELLON (as ) Trustee under various Pooling and Servicing ) Assigned to: Kapnick, J. Agreements and Indenture Trustee ) under various Indentures), et al. ) ) Petitioners, ) ) for an order, pursuant to C.P.L.R. § 7701, seeking ) judicial instructions and approval of a proposed ) settlement. ) _________________________________________ ) EXPERT REPORT OF DANIEL R. FISCHEL I. QUALIFICATIONS 1. I am President of Compass Lexecon, a consulting firm that specializes in the application of economics to a variety of legal and regulatory issues. I am also the Lee and Brena Freeman Professor of Law and Business Emeritus at The University of Chicago Law School. I have served previously as Dean of The University of Chicago Law School, Director of the Law and Economics Program at The University of Chicago, and as Professor of Law and Business at The University of Chicago Graduate School of Business, the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, and at the Northwestern University Law School. 2. Both my research and my teaching have concerned the economics of corporate law and financial markets. I have published approximately fifty articles in leading legal and economics journals and am coauthor, with Judge Frank Easterbrook of - 1 - the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, of the book The Economic Structure of Corporate Law (Harvard University Press). Courts of all levels, including the Supreme Court of the United States and the Delaware Supreme Court, have cited my articles as authoritative. -

Best Bank M&A Deals

Ranking banking BEST BANK M&A DEALS 2020 1 BEST BANK M&A DEALS SPONSORED BY: 2 Defining Success in M&A ow do you define success in bank M&A? M&A can have a transformative impact upon an organization, par- ticularly a community or regional bank. The organization gets larger and gains more operational scale. Lending officers are now empowered to make bigger loans in the bank’s market. The acquirer can make new loans and grow deposits in new markets, and expand market share in its existing geographic footprint. This should all have a positive long-term effect on the metrics we tend to track when evaluating the performance of a bank — its tangible book value per share, profitability measurements like return on assets and earn- ings per share growth, and its efficiency ratio, among other variables. These are all important indicators in understanding the financial impact H of the deal on the combined entity. But it’s the intangible elements — leadership, talent, culture and communication — that drive those metrics and inform a deal’s ultimate success. Bank Director’s core mission for its almost 30-year history has been focused on the stra- tegic issues facing bank executives and boards. How your bank chooses to approach M&A — whether by blazing a path as an active acquirer, focusing on organic growth opportunities or considering whether it’s the right time to sell — impacts your organization’s future. For this reason, the 2020 RankingBanking study, sponsored by Crowe LLP, focuses on the best M&A transactions across several categories, including by asset size and market reaction. -

1 April 28, 2017 THIS TRANSMITTAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT INFORMATION THAT IS of INTEREST to the BENEFICIAL OWNERS of the SUBJECT

April 28, 2017 THIS TRANSMITTAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT INFORMATION THAT IS OF INTEREST TO THE BENEFICIAL OWNERS OF THE SUBJECT CERTIFICATES. IF APPLICABLE, ALL DEPOSITORIES, CUSTODIANS AND OTHER INTERMEDIARIES RECEIVING THIS NOTICE ARE REQUESTED TO EXPEDITE RE-TRANSMITTAL TO SUCH BENEFICIAL OWNERS IN A TIMELY MANNER. Time Sensitive Informational Notice Regarding the Hearing Date for Trust Instructional Proceeding For the Trusts Listed on Exhibits 1-A and 1-B (“Trusts”) -and- Update on Settlement Concerning Litigation Against the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation as Receiver for Washington Mutual Bank, JPMorgan Chase, N.A., and Washington Mortgage Securities Corporation (the “Litigation”) To the Holders of Certain Residential Mortgage Backed Securities Sponsored by Washington Mutual Bank, Long Beach Mortgage Company, Washington Mutual Mortgage Securities Corporation or Washington Mutual Asset Acceptance Corp. (Collectively, the “WaMu Securities”) CLASSES OF CERTIFICATES AND CUSIP NUMBERS LISTED ON EXHIBIT 21 Deutsche Bank National Trust Company (hereinafter, the “Trustee”) acts as trustee (including as trustee for certain related supplemental interest trusts) under the governing documents, which may include Pooling and Servicing Agreements, Servicing Agreements, Sale and Servicing Agreements, Trust Agreements or Indentures (collectively, the “Governing Documents”) for the residential mortgage backed securities trusts (collectively, the “WaMu Securities”). For additional information, holders of WaMu Securities are referred to the Trustee’s Report Regarding Status of Litigation to Enforce Certain Trust Claims dated October 17, 2012 and updates dated July 28, 2014, October 16, 2014, June 12, 2015, June 29, 2015, April 18, 2016, August 8, 2016, and August 19, 2016 (collectively the “Litigation Status Reports”) and the Informational Notice Regarding the Hearing Date for Trust Instructional Proceeding for Trusts Listed on Exhibits 1-A and 1-B, dated December 22, 2016.