SYRIZA, Left Populism and the European Migration Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India – Greece Bilateral Relations Basic Facts About the Country Name

India – Greece Bilateral Relations Basic facts about the country Name and capital of the country: Hellenic Republic, Athens Provinces/Administrative Divisions: 13 regions and 1 autonomous region -AgionOros (Mt. Athos). Population: 10.8 million (as per 2011 census - ELSTAT) Currency: Euro Language spoken: Greek Time: 3½ hours behind IST in winter; 2½ hours in summer Head of State: Mr. ProkopisPavlopoulos Head of Government: Mr. Alexis Tsipras Foreign Minister: Mr. Nikos Kotzias Political Relations India and Greece established diplomatic relations in May 1950. India opened its resident Embassy in Athens in March 1978. Interaction between India and Greece goes back to antiquity. In modern times, the two countries have developed a warm relationship based on a common commitment to democracy, peace and development in the world and to a social system imbued with principles of justice and equality. India and Greece also share common approaches to many international issues, such as UN reforms and Cyprus. Greece has consistently supported India’s core foreign policy objectives. Greece participated with India in the Six-National Delhi Declaration on Nuclear Disarmament in 1985. The relationship has progressed smoothly over the last 65 years. Bilateral VVIP visits have taken place regularly. President A.P.J. Abdul Kalam visited Greece in April 2007. Greek Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis visited India in January 2008. The two countries held Foreign Office Consultations in New Delhi on 26 October 2016 and discussion focused on various issues of bilateral, regional and international importance. Commercial Relations India and Greece are keen to increase their commercial and investment contacts.Greece looks for Indian investments in their program of privatization of public assets. -

First Thoughts on the 25 January 2015 Election in Greece

GPSG Pamphlet No 4 First thoughts on the 25 January 2015 election in Greece Edited by Roman Gerodimos Copy editing: Patty Dohle Roman Gerodimos Pamphlet design: Ana Alania Cover photo: The Zappeion Hall, by Panoramas on Flickr Inside photos: Jenny Tolou Eveline Konstantinidis – Ziegler Spyros Papaspyropoulos (Flickr) Ana Alania Roman Gerodimos Published with the support of the Politics & Media Research Group, Bournemouth University Selection and editorial matter © Roman Gerodimos for the Greek Politics Specialist Group 2015 All remaining articles © respective authors 2015 All photos used with permission or under a Creative Commons licence Published on 2 February 2015 by the Greek Politics Specialist Group (GPSG) www.gpsg.org.uk Editorial | Roman Gerodimos Continuing a tradition that started in 2012, a couple of weeks ago the Greek Politics Specialist Group (GPSG) invited short commentaries from its members, affiliates and the broader academ- ic community, as a first ‘rapid’ reaction to the election results. The scale of the response was humbling and posed an editorial dilemma, namely whether the pamphlet should be limited to a small number of indicative perspectives, perhaps favouring more established voices, or whether it should capture the full range of viewpoints. As two of the founding principles and core aims of the GPSG are to act as a forum for the free exchange of ideas and also to give voice to younger and emerging scholars, it was decided that all contributions that met our editorial standards of factual accuracy and timely -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTION IN GREECE 7th July 2019 European New Democracy is the favourite in the Elections monitor Greek general election of 7th July Corinne Deloy On 26th May, just a few hours after the announcement of the results of the European, regional and local elections held in Greece, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA), whose party came second to the main opposition party, New Analysis Democracy (ND), declared: “I cannot ignore this result. It is for the people to decide and I am therefore going to request the organisation of an early general election”. Organisation of an early general election (3 months’ early) surprised some observers of Greek political life who thought that the head of government would call on compatriots to vote as late as possible to allow the country’s position to improve as much as possible. New Democracy won in the European elections with 33.12% of the vote, ahead of SYRIZA, with 23.76%. The Movement for Change (Kinima allagis, KINAL), the left-wing opposition party which includes the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), the Social Democrats Movement (KIDISO), the River (To Potami) and the Democratic Left (DIMAR), collected 7.72% of the vote and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), 5.35%. Alexis Tsipras had made these elections a referendum Costas Bakoyannis (ND), the new mayor of Athens, on the action of his government. “We are not voting belongs to a political dynasty: he is the son of Dora for a new government, but it is clear that this vote is Bakoyannis, former Minister of Culture (1992-1993) not without consequence. -

REPORT Volume 45 Number 257 AMERICAN HELLENIC INSTITUTE JUNE 2018

REPORT Volume 45 Number 257 AMERICAN HELLENIC INSTITUTE JUNE 2018 American Hellenic, American Jewish Groups Hail Third Three-Country Leadership Honorees (L-R): Phil Angelides, Isidoros Garifalakis, Nancy Papaionnou, Tim Tassopoulos. Mission AHI Hosts 43rd Anniversary Awards Dinner The American Hellenic Institute (AHI) hosted its 43rd Anniversary Hellenic Heritage Achievement and National Public Service Awards Dinner, March 3, 2018, Capital Hilton, Washington, D.C. AHI honored a distinguished set of awardees based upon their important career achievements and contributions to the Greek American community or community at-large. They were: Nancy Papaioannou, President, Atlantic Bank of New York; Isidoros Garifalakis, Businessman and Philanthropist; Tim Tassopoulos, President and Chief Operating Officer, Chick-fil-A; and Phil Angelides, former California (L-R) Delegation Heads Stephen Greenberg, State Treasurer, former Chairman of the U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, Chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations; Nick and Businessman. Larigakis, President of AHI; Prime Minister Alexis Larry Michael, “Voice of the Redskins,” and chief content officer and senior vice Tsipras, Prime Minister of Greece; Carl R. Hollister, president, Washington Redskins; was the evening’s emcee. AHI Board of Directors Supreme President of AHEPA; Gary P. Saltzman, International President of B’nai B’rith International. Member Leon Andris introduced Michael. The Marines of Headquarters Battalion presented the colors and the -

Euroscepticism in Political Parties of Greece

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND DIPLOMACY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE Eimantas Kočanas EUROSCEPTICISM IN POLITICAL PARTIES OF GREECE Master’s Thesis Contemporary European politics study program, state code 621L20005 Political sciences study direction Supervisor: Prof. Doc. Mindaugas Jurkynas Defended: PMDF Dean - Prof. Doc. Šarūnas Liekis Kaunas 2016 European Union is like a painting displayed in a museum. Some admire it, others critique it, and few despise it. In all regards, the fact that the painting is being criticized only shows that there is no true way to please everybody – be it in art or politics. - Author of this paper. 1 Summary Eimantas Kocanas ‘Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece’, Master’s Thesis. Paper supervisor Prof. Doc. Mindaugas Jurkynas, Kaunas Vytautas Magnus University, Department of Diplomacy and Political Sciences. Faculty of Political Sciences. Euroscepticism (anti-EUism) had become a subject of analysis in contemporary European studies due to its effect on governments, parties and nations. With Greece being one of the nations in the center of attention on effects of Euroscepticism, it’s imperative to constantly analyze and research the eurosceptic elements residing within the political elements of this nation. Analyzing eurosceptic elements within Greek political parties, the goal is to: detect, analyze and evaluate the expressions of Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece. To achieve this: 1). Conceptualization of Euroscepticism is described; 2). Methods of its detection and measurement are described; 3). Methods of Euroscepticism analysis are applied to political parties of Greece in order to conclude what type and expressions of eurosceptic behavior are present. To achieve the goal presented in this paper, political literature, on the subject of Euroscepticism: 1). -

Gender Stereotypes and Media Bias in Women's

Gender Stereotypes and Media Bias in Women’s Campaigns for Executive Office: The 2009 Campaign of Dora Bakoyannis for the Leadership of Nea Dimokratia in Greece by Stefanos Oikonomou B.A. in Communications and Media Studies, February 2010, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of College of Professional Studies of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Studies August 31, 2014 Thesis directed by Michael Cornfield Associate Professor of Political Management Acknowledgments I would like to thank my parents, Stella Triantafullopoulou and Kostas Oikonomou, to whom this work is dedicated, for their continuous love, support, and encouragement and for helping me realize my dreams. I would also like to thank Chrysanthi Hatzimasoura and Philip Soucacos, for their unyielding friendship, without whom this work would have never been completed. Finally, I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Michael Cornfield for his insights and for helping me cross the finish line; Professor David Ettinger for his guidance during the first stage of this research and for helping me adjust its scope; and the Director of Academic Administration at The Graduate School of Political Management, Suzanne Farrand, for her tremendous generosity and understanding throughout this process. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..ii List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………….vi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………….vii -

2019 © Timbro 2019 [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019

TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX 2019 © Timbro 2019 www.timbro.se [email protected] Layout: Konow Kommunikation Cover: Anders Meisner FEBRUARY 2019 ABOUT THE TIMBRO AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM INDEX Authoritarian Populism has established itself as the third ideological force in European politics. This poses a long-term threat to liberal democracies. The Timbro Authoritarian Populism Index (TAP) continuously explores and analyses electoral data in order to improve the knowledge and understanding of the development among politicians, media and the general public. TAP contains data stretching back to 1980, which makes it the most comprehensive index of populism in Europe. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • 26.8 percent of voters in Europe – more than one in four – cast their vote for an authoritarian populist party last time they voted in a national election. • Voter support for authoritarian populists increased in all six elections in Europe during 2018 and has on an aggregated level increased in ten out of the last eleven elections. • The combined support for left- and right-wing populist parties now equals the support for Social democratic parties and is twice the size of support for liberal parties. • Right-wing populist parties are currently growing more rapidly than ever before and have increased their voter support with 33 percent in four years. • Left-wing populist parties have stagnated and have a considerable influence only in southern Europe. The median support for left-wing populist in Europe is 1.3 percent. • Extremist parties on the left and on the right are marginalised in almost all of Europe with negligible voter support and almost no political influence. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 The human capital of Greece is its single best hope for the future. Giving young people who face a 50% unemployment rate in Greece the opportunity to receive training, internships, mentorship, and compensation is a priority of THI. Together, we can build a better tomorrow for Greece, and give the hundreds of thousands, who have been forced to leave to find work, the possibility to return to their homeland. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 1 2 3 THI New Leaders The 2nd Annual Venture Fair The 3rd Annual Gala 5 13 29 4 5 6 THI Programs THI Around the World Friends of THI 51 77 87 7 8 9 THI Board Member Profile: THI Donor Profiles Financials Corinne Mentzelopoulos 91 99 103 ON THE COVER: The many points of light of THI’s partners, friends and beneficiaries EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President Bill Clinton, Honorary Chairman Andrew N. Liveris, Chairman Dean Dakolias George A. David Muhtar Kent Nicholas Lazares George M. Logothetis Dennis Mehiel Alexander Navab John Pappajohn George Sakellaris George P. Stamas, President Harry Wilson Father Alexander Karloutsos, Honorary Advisor Te fag of the Φιλική Εταιρεία, BOARD MEMBERS the “Society of Friends.” Maria Allwin Drake Behrakis It has the letters "ΗΕΑ" (Ή ΕλευθερίΑ") John P. Calamos, Sr. and "ΗΘΣ" ("Ή ΘάνατοΣ") Aris Candris John Catsimatidis which are a shorthand for the words Achilles Constantakopoulos “Ελευθερία ή θάνατος” – “Freedom or Death.” Jeremy Downward William P. Doucas John D. Georges Arianna Hufngton Constantine Karides Savas Konstantinides John S. Koudounis Amb. Eleni T. Kounalakis Ted Leonsis Alexander Macridis George Marcus Panos Marinopoulos Corinne Mentzelopoulos C. -

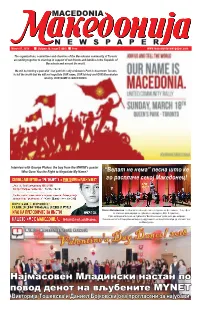

Најмасовен Младински Настан По Повод Денот На Вљубените MYNET Викторија Тошевска И Даниел Бојковски Беа Прогласени За Најубави Страница 2 Македонија March 01, 2018

MACEDONIA NEWSPAPER March 01, 2018 Volume 34, Issue 5 (401) Free www.macedonianewspaper.com The organizations, committees and churches of the Macedonian community of Toronto are uniting together to stand up in support of our friends and families in the Republic of Macedonia and around the world. We will be holding a peaceful - but patriotic rally at Queen's Park in downtown Toronto to tell the world that we will not negotiate OUR name, OUR history and OUR Macedonian identity. OUR NAME IS MACEDONIA. Interview with George Plukov, the boy from the MHRMI’s poster Who Gave You the Right to Negotiate My Name? “Велат не нема” песна што ќе го расплаче секој Македонец! Влатко Миладиноски е победник на овогодинешното издание на фестивалот “Гоце фест” со освоена прва награда од публиката, наградата ,,Војо Стојаноски,,. Прво наградената песна од публиката “Велат не нема” доби уште две награди: Сценски настап и Специјална награда од здружението на децата бегалци од егејскиот дел на Македонија. Најмасовен Младински настан по повод денот на вљубените MYNET Викторија Тошевска и Даниел Бојковски беа прогласени за најубави Страница 2 Македонија March 01, 2018 Извадок од монодрамата на Јордан Плевнеш „Така зборува Исидор Солунски“ Е месечен весник, гласи- ло на Македонците во Северна Америка. Тешко ми е Татковино… тешко многу ми е… Излегува во првата сед- Ми се скамени летот во ‘рбетот, оти ти ми беше и крило и мица од месецот. небо. Секоја ноќ те сонувам, на Белата Кула во Солун, за- Првиот број на “Македо- гледана во Белото море, како ги чекаш своите големи синови нија“ излезе на први ноем- ври 1984 година и оттогаш Филип и Александар, да те избават од овој голем срам, во кој весникот излегува редов- те втурнаа предавниците. -

Election and Aftermath

Order Code RS20575 Updated June 9, 2000 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Greece: Election and Aftermath (name redacted) Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Summary Prime Minister Simitis of Greece called an early election for April 9, 2000 because he believed that his government’s achievement in meeting the criteria for entry into the European Monetary Union (EMU) would return his PanHellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) party to power. PASOK’s narrow victory endorsed Simitis’s decision, but the opposition New Democracy’s (ND) strong showing also validated Costas Karamanlis’s leadership of that party. The election continued a trend toward bipolarism, as votes for smaller parties, except for the Communists, declined appreciably. Simitis reappointed most key members of his previous government, and brought in close allies and technocrats to carry out a revitalized domestic agenda. In foreign policy, the government will try to continue the Greek-Turkish rapprochement, to help stabilize the Balkans, and to move closer to Europe through the EMU and the European Security and Defense Policy. Greek-U.S. relations are warm, but intermittently troubled by differences over the future of the former Yugoslavia, terrorism and counterterrorism in Greece, and minor issues. This report will be updated if developments warrant. Introduction1 On February 4, 2000, Prime Minister Costas Simitis called an early election for April 9, six months before his government’s term was to expire. On March 9, parliament reelected President Costas Stephanopoulos and Greece applied for membership in the European Monetary Union (EMU) single currency zone. -

The Making of SYRIZA

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Panos Petrou The making of SYRIZA Published: June 11, 2012. http://socialistworker.org/print/2012/06/11/the-making-of-syriza Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. June 11, 2012 -- Socialist Worker (USA) -- Greece's Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA, has a chance of winning parliamentary elections in Greece on June 17, which would give it an opportunity to form a government of the left that would reject the drastic austerity measures imposed on Greece as a condition of the European Union's bailout of the country's financial elite. SYRIZA rose from small-party status to a second-place finish in elections on May 6, 2012, finishing ahead of the PASOK party, which has ruled Greece for most of the past four decades, and close behind the main conservative party New Democracy. When none of the three top finishers were able to form a government with a majority in parliament, a date for a new election was set -- and SYRIZA has been neck-and-neck with New Democracy ever since. Where did SYRIZA, an alliance of numerous left-wing organisations and unaffiliated individuals, come from? Panos Petrou, a leading member of Internationalist Workers Left (DEA, by its initials in Greek), a revolutionary socialist organisation that co-founded SYRIZA in 2004, explains how the coalition rose to the prominence it has today. -

El Salto 19-07 Mission Accomplished. but After the Game Is Before The

El salto 19-07 Mission Accomplished. But after the Game is before the Game Wolfgang Streeck Six weeks after the election of a new European Parliament, while winners and losers in Stras- burg and Brussels were still fighting over the spoils (likely the high point of their political life during the next five years), Alexis Tsipras was voted out as Prime Minister of Greece. In the preceding European election, in 2014, Tsipras had been the top candidate (the Spitzenkandi- dat) and the great political hope of the (more or less) united European Left. One year later he was elected Prime Minister of his country and tried to incite a revolt against the euro austerity regime that was and still is suffocating the economies of Southern Europe. Under his leader- ship, the Greek government refused to sign the Memoranda of Understanding (the MoUs) presented to it by the Eurogroup, containing long lists of policy measures designed to rescue the euro by strangling the Greek people. But it took no longer than half a year of hardball di- plomacy, including the European Central Bank cutting off the supply of euro cash to Greek banks, until Tsipras was forced to cave in. Advised by Angela Merkel on the high art of statesmanship, he ultimately signed a MoU more punitive than anything ever forced on his predecessors, on the day after he had won a referendum in which Greek voters had, at his re- quest, instructed him not to do so. Tsipras’ landslide defeat (with 31.5 percent for his party, Syriza, compared to 39.9 percent for the opposition, the New Democracy Party) cannot have come as a surprise, nor can the record-low turnout of 58 percent.