Non-Professional Translation in the City of Antwerp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lions Clubs International Liability Insurance Program

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL LIABILITY INSURANCE PROGRAM GENERAL NAMED INSURED The International Association of Lions Clubs has a program of Commercial General Liability The International Association of Lions Clubs, all Insurance that covers Lions on a worldwide Districts (Single, Sub - and Multiple) of said basis. The policy is issued by ACE American Association, all individual Lions Clubs Insurance. All Clubs and Districts are organized or chartered by said Association, Leo automatically insured. No action on your part Clubs, Lioness Clubs and any other Lions is necessary. organization owned, controlled or operated by a Named Insured or by individual Lion members The purpose of this booklet is to describe the while acting on behalf of a Named Insured. plan in a manner that will enable Lions to understand its application to their activities. The If an entity falls within this definition, it is a Provisions of the policy apply to most normal named insured under the policy. Note, however, liability exposures of Lions Clubs and Districts, that the Constitution and By-Laws of the including their functions and activities. Claims International Association of Lions Clubs provide arising out of liability for the operation, use, or that no individual or entity other than Lions maintenance of aircraft, automobiles owned by Clubs and Districts may use the Lions name or Lions organizations and certain water- craft are emblem without a specific license granted by the not covered (See “Exclusions”). These pages are International Board of Directors. (See question explanatory only and cannot cover all possible number 20.) We cannot issue a certificate of situations. -

Participants Brochure REPUBLIC of KOREA 10 > 17 June 2017 BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION

BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION Participants Brochure REPUBLIC OF KOREA 10 > 17 June 2017 BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION 10 > 17 June 2017 Organised by the regional agencies for the promotion of Foreign Trade & Investment (Brussels Invest & Export, Flanders Investment & Trade (FIT), Wallonia Export-Investment Agency), FPS Foreign Affairs and the Belgian Foreign Trade Agency. Publication date: 10th May 2017 REPUBLIC OF KOREA This publication contains information on all participants who have registered before its publication date. The profiles of all participants and companies, including the ones who have registered at a later date, are however published on the website of the mission www.belgianeconomicmission.be and on the app of the mission “Belgian Economic Mission” in the App Store and Google Play. Besides this participants brochure, other publications, such as economic studies, useful information guide, etc. are also available on the above-mentioned website and app. REPUBLIC OF KOREA BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSIONS 4 CALENDAR 2017 IVORY COAST 22 > 26 October 2017 CALENDAR 2018 ARGENTINA & URUGUAY June 2018 MOROCCO End of November 2018 (The dates are subject to change) BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION REPUBLIC OF KOREA Her Royal Highness Princess Astrid, Princess mothers and people lacking in education and On 20 June 2013, the Secretariat of the Ot- of Belgium, was born in Brussels on 5 June skills. tawa Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention 1962. She is the second child of King Albert announced that Princess Astrid - as Special II and Queen Paola. In late June 2009, the International Paralym- Envoy of the Convention - would be part of pic Committee (IPC) Governing Board ratified a working group tasked with promoting the After her secondary education in Brussels, the appointment of Princess Astrid as a mem- treaty at a diplomatic level in states that had Princess Astrid studied art history for a year ber of the IPC Honorary Board. -

The Latin American Pentecostal Community of Superdiverse Berchem

The Latin American Pentecostal community of superdiverse Berchem Marco Jose Rueda Aguila Anr: 688984 Master’s Thesis Communication and Information Sciences Specialization: Data Journalism Faculty of Humanities Tilburg University, Tilburg Supervisor: prof. dr. J.M.E. Blommaert Second Reader: dr. M. Spotti October 2016 Abstract: The globalization and the gradual increase of worldwide information and communication technologies has brought deep transformations in some of the landscapes of European urban areas. Such changes are related as well with the escalation of international migration, which means an unprecedented mixture of people with different cultural and ethnic backgrounds living in the same environment. This phenomenon, which is called super-diversity, demands new formulas aimed at solving people identity, adaptation and integration challenges arisen from this complex situation. In this context, the ethnographic study of a community reveals itself as a powerful technique to observe and comprehend who are them, where are they from and how do they relate with their host country as well as with their country of origin. In particular, this study revolves around the Latin American Pentecostal community of Berchem, an Antwerp’s district in which ‘superdiverse’ features are found. Pentecostal churches are one of the most significant appearances in the neighbourhood within the last ten years. The research discloses the way in which Pentecostal churchers are connected to the last stage of migration by investigating their role within the community in which they operate. These places, which are a matter of debate among public institutions in Belgium, provide social and emotional assistance to their converts, which makes of them important infrastructures in superdiverse environments. -

Robert Laffont, Soon Be Forgotten

FRENCH PUBLISHING 2017 FRANKFURT GUEST OF HONOUR Special issue - October 2017 CHRISTEL PETITCOLLIN our number 1 bestselling author in SELF-IMPROVEMENT JePenseMieux COUV_Mise en page 1 10/02/2015 15:26 Page1 La parution de Je pense trop a été (et est encore !) une aventure extraordinaire. Je n’avais jamais reçu autant de lettres, d’e-mails, de posts, de textos à propos d’un de mes livres ! Vous m’avez fait part de votre enthousiasme, de votre soulagement et vous m’avez bombardée de questions : sur les moyens d’endiguer votre hyperémotivité, de développer votre confiance en vous, de bien vivre votre surefficience dans le monde du travail et dans vos relations amoureuses… Vous avez abondamment commenté le livre. Je me suis donc appuyée sur vos réactions, vos avis, vos témoignages et vos astuces personnelles pour répondre à toutes ces questions. Je pense trop est devenu le socle à partir duquel j’ai élaboré avec votre participation active de nouvelles pistes de réflexion pour mieux gérer votre cerveau. Je pense mieux est un livre-lettre, un livre-dialogue, Over destiné aux lecteurs qui connaissent déjà Je pense trop et qui en attendent la suite. 175,000 Christel Petitcollin est conseil et formatrice en communication et développement personnel, conférencière et écrivain. Passionnée de relations humaines, elle sait donner à ses livres un ton simple, accessible et concret. Elle est l’auteur des best-sellers Échapper aux manipulateurs, Divorcer d’un manipu- copies lateur, Enfants de manipulateurs et Je pense trop. © Anna Skortsova © sold in France -

Road Safety Review: Belgium Know Before You Go Driving Culture Driving Is on the Right

Association for Safe International Road Travel Road Safety Review: Belgium Know Before You Go Driving Culture Driving is on the right. • A driving study named Belgian drivers the most Drivers are required to carry proof of third party aggressive in Europe. insurance, passport and vehicle registration. Non-EU • Drivers typically blast horns to express irritation. drivers must carry an International Driving Permit (IDP). • Road rage is common. Pedestrian crashes are the second leading cause of road • Drivers often use rude gestures to communicate with deaths in Belgium. other motorists. Belgium is one of the least safe countries in Europe • Despite laws prohibiting cell phone use while driving, for road travel, ranking 23 out of 30 countries studied. Belgian drivers frequently use electronic devices Reasons include speeding, and use of alcohol and while operating motorized vehicles. One in ten drugs. Blood alcohol limit is below 0.05 g/dl for all drivers. Belgian drivers has been in a crash involving use of a There are 5.8 road deaths per 100,000 people in smartphone. Belgium, compared to 2.8 in Sweden and 3.1 in the UK. • Speeding is widespread. Road Conditions • There are 118,414 km (73,579 miles) of paved roads in Belgium, including 1,747 km (1,085 miles) of expressways. • Roads are generally in good condition and are well maintained. • Highway lightingis adequate; lighting along rural roads may be insufficient or nonexistent. • Many highways are overcrowded. • Highways are designated by the letter “A,” followed by a number; and may also carry the European route, indicated by the letter “E,” followed by a number. -

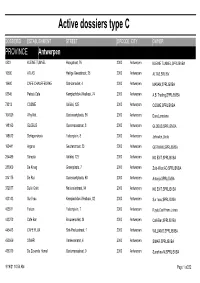

Active Dossiers Type C

Active dossiers type C DOSSIERID ESTABLISHMENT STREET ZIPCODE CITY OWNER PROVINCE Antwerpen 4523 KLEINE TUNNEL Hoogstraat, 76 2000 Antwerpen KLEINE TUNNEL,SPRL/BVBA 16580 ATLAS Heilige Geeststraat, 25 2000 Antwerpen ALTAS,SRL/BV 19680 CAFE CHAUFFEURKE Sint-Jansvliet, 4 2000 Antwerpen MASAN,SPRL/BVBA 63345 Petra's Cafe Kempischdok-Westkaai, 74 2000 Antwerpen A.B. Trading,SPRL/BVBA 73312 COSME Italiëlei, 125 2000 Antwerpen COSME,SPRL/BVBA 104029 Why Not Oudevaartplaats, 56 2000 Antwerpen Dura,Loredana 148160 GLOBUS Oudemansstraat, 8 2000 Antwerpen GLOBUS,SPRL/BVBA 148612 Schippershoek Falconplein, 8 2000 Antwerpen Johnston,Linda 160441 Argana Geuzenstraat, 23 2000 Antwerpen GERWAW,SPRL/BVBA 264489 Sarepta Italiëlei, 123 2000 Antwerpen NO EXIT,SPRL/BVBA 283969 De Kroeg Groenplaats, 7 2000 Antwerpen Zuid-West AD,SPRL/BVBA 314175 De Rui Oudevaartplaats, 60 2000 Antwerpen Antanja,SPRL/BVBA 372877 Dulle Griet Nationalestraat, 94 2000 Antwerpen NO EXIT,SPRL/BVBA 403143 Sur l'eau Kempischdok-Westkaai, 82 2000 Antwerpen Sur l'eau,SPRL/BVBA 405511 Falcon Falconplein, 7 2000 Antwerpen Ruyts,Carl Frans Johan 443272 Café Bar Brouwersvliet, 34 2000 Antwerpen Café Bar,SPRL/BVBA 445413 CAFE FLUX Sint-Paulusstraat, 1 2000 Antwerpen WILLIAMS,SPRL/BVBA 450569 SIMAR Varkensmarkt, 4 2000 Antwerpen SIMAR,SPRL/BVBA 456319 De Zevende Hemel Oudemansstraat, 9 2000 Antwerpen Sunshine-M,SPRL/BVBA 9/16/21 10:54 AM Page 1 of232 DOSSIERID ESTABLISHMENT STREET ZIPCODE CITY OWNER 459399 De Schelde Scheldestraat, 36 2000 Antwerpen SOUTH INVEST,SCS/Comm.V 474854 Antwerp -

USA - TEXAS 3 > 11 December 2016 Publication Date: 20 October 2016

BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION Participants Brochure USA - TEXAS 3 > 11 December 2016 Publication date: 20 October 2016 This publication contains information on all participants who have registered before its publication date. The profiles of all participants and companies, including the ones who have registered at a later date, are however published on the website of the mission www.belgianeconomicmission.be and on the app of the mission “Belgian Economic Mission” in the App Store and Google Play. Besides this participants brochure, other publications, such as economic studies, useful information guide, etc. are also available on the above-mentioned website and app. BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION 3 > 11 December 2016 Organized by the regional agencies for the promotion of Foreign Trade & Investment (Brussels Invest & Export, Flanders Investment & Trade (FIT), Wallonia Export-Investment Agency), FPS Foreign Affairs and the Belgian USA - TEXAS Foreign Trade Agency. USA - TEXAS 4 BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSIONS CALENDAR 2017 REPUBLIC OF KOREA 10 > 16 June 2017 IVORY COAST mid-October 2017 (The dates are subject to change) USA - TEXAS HRH PRINCESS ASTRID 6 OF BELGIUM REPRESENTATIVE OF HIS MAJESTY THE KING BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION © FPS Chancery of the Prime Minister-Directorate-General External Communication-Belgium-Photographe: Shimera-Ansotte Her Royal Highness Princess Astrid, Princess mothers and people lacking in education and On 20 June 2013, the Secretariat of the of Belgium, was born in Brussels on 5 June skills. Ottawa Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention 1962. She is the second child of King Albert announced that Princess Astrid - as Special II and Queen Paola. In late June 2009, the International Envoy of the Convention - would be part of Paralympic Committee (IPC) Governing Board a working group tasked with promoting the After her secondary education in Brussels, ratified the appointment of Princess Astrid as treaty at a diplomatic level in states that had Princess Astrid studied art history for a year a member of the IPC Honorary Board. -

Belgium Vicinal Railways

BELGIUM VICINAL RAILWAYS (1) - SL 299 01.05.20 page 1 of 58 PASSENGER STATIONS & STOPS excluding Mons-Charleroi area (see Belgium Vicinal Rlys (2), SL180); including Tramways Liege-Seraing & Glossary Based on Indicateur Officiel/Officiële Reisgids 1895 (z), 1914 (a), 1925 (b), 1938 (c), 1952 (d), 1976 (e) & current Kusttram TT (f). Also, Indicateurs 1906/1907 (p), 1930 (q), 1945 (s),1950 (t) & local SNCV/NMVB TTs Kustlynen 1925, Luxembourg 1957, Antwerpen 1959, Brabant 1969 & West Vlaanderen 1971, personal observation 1960's, The Vicinal Story 1885-1991 (WJK Davies), Rail Atlas Vicinal and Les C.de F. Vicinaux de Brabant. #: from Histories. tm: terminus at date shown Former names: [ ] Distances in tariff kilometres; Gauge 1.0m unless noted; E: electrified lines; [90]: route nos. Bilingual representation: First name shown as current or final timetables, usually Flemish/French in the bilingual Brussels area and in the Flemish speaking areas north, north-east and west of Brussels; French/Flemish (or German)in the French (and part German) speaking areas south and south-east of Brussels. After WW2, the alternative French or Flemish name was gradually discontinued in most areas. Only the Brussels area remains bilingual. All French names on Kusttram (577) have been shown as former names. Until after 1907, TTs showed most minor stops in the main table. By 1914, most of the minor stops were only shown in footnotes, making stops opened or renamed after 1907 difficult to locate (1970's bus timetables have enabled many to be located). Some line TTs did not show the minor stops, particularly suburban lines after electrification. -

Download Programme Antwerp Barok 2018

FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 ANTWERP BAROQUE 2018 BAROQUE ANTWERP PROGRAMME Programme www.antwerpbaroque2018.be Cultural city festival I june 2018 — january 2019 © Paul Kooiker, uit de serie Sunday, 2011 — vu: Wim Van Damme, Francis Wellesplein 1, 2018 Antwerpen 1, 2018 Wellesplein Francis Damme, — vu: Wim Van 2011 uit de serie Sunday, Kooiker, © Paul Paul Kooiker The cover photo was taken by the Dutch photographer Paul Kooiker. See more of his surprising nudes at the FOMU. expo Paul Kooiker 71 Behind the scenes Frieke Janssens The striking portraits in this portrayed. The ostrich feathers brochure were taken by the in Herr Seele’s portrait epitomise Belgian photographer Frieke exoticism and lavish excess. Janssens. “Baroque suits me, it Yvon Tordoir also paints skulls suits my photographic style.” in his street art but a skull also Janssens mainly studied the embodies power, fearlessness and self-portraits of Rubens and the rebelliousness. The soap bubbles in portrait of his wife, Isabella Brant. the portrait of the musician Pieter “I refer to the pose, the attributes, Theuns symbolise the “ephemeral” that same atmosphere in my while the peacock represents photos. People often associate pride and vanity. I thought this Baroque with exuberance and was a perfect element for Stef excess, whereas my portraits are Aerts and Damiaan De Schrijver, almost austere. Chiaroscuro is a who work in the theatre. I chose typically Baroque effect though. herring, the most popular ocean I use natural daylight, which fish in the sixteenth century for makes my photos look almost like the ladies of Alle Dagen Honger. paintings.” I wanted to highlight the female “I also wanted the portraits power of Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven to have a contemporary feel. -

Smartphone Applications

Every Æ Aware Project no. 265432 EveryAware Enhance Environmental Awareness through Social Information Technologies http://www.everyaware.eu Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) Future and Emerging Technologies of the Information Communication Technologies (ICT FET Open) D1.2: Final report on: sensor selection, calibration and testing; EveryAware platform; smartphone applications Period covered: from 01/09/2012 to 28/02/2014 Date of preparation: 28/02/2014 Start date of project: March 1st, 2011 Duration: 36 months Due date of deliverable: Apr 30th, 2014 Actual submission date: Apr 30th, 2014 Distribution: Public Status: Final Project coordinator: Vittorio Loreto Project coordinator organisation name: Fondazione ISI, Turin, Italy (ISI) Lead contractor for this deliverable: Fondazione ISI, Turin, Italy (ISI) 2014 c Copyright lies with the respective authors and their institutions Page 2 of 41 EveryAware: Enhance Environmental Awareness through Social Information Technologies Every Æ Contents Aware 1 The sensor box for air quality monitoring 7 1.1 The AirProbe mobile application . .7 1.1.1 Live Track mode . .8 1.1.2 Synchronization mode . .8 1.1.3 Browsing mode . .9 2 The smartphone for noise pollution monitoring 10 3 Calibration of the sensor box 11 3.1 Introduction . 11 3.2 EveryAware sensorbox calibration approach . 11 3.3 Calibration Stages . 14 3.3.1 Stationary Calibration in Turin . 14 3.3.2 Parameterization of the calibration model . 14 3.3.3 Testing of the calibration model . 16 3.4 Mobile and Indoor Calibration for Turin . 18 3.5 Calibration for the international test case . 19 3.5.1 Collection of representative data . 19 3.5.2 Model training and testing . -

Urban Development in Antwerp in Antwerp Urban Development Antwerp Designing

Urban development in Antwerp Designing Antwerp Urban development in Antwerp Urban development Designing Antwerp Designing Project index CityStad and en districtsdistricten Colophon Berendrecht-Zandvliet-Lillo Editor Alix Lorquet Amuz 129 Antwerp Berchem 33 Editorial committee Diamond District 33 Kristiaan Borret, Patricia De Somer, Hardwin De Wever, Ruben Haerens, Pieter Tan, Katlijn Van der Veken, Yrsa Vermaut Barreiro 88 Boekenbergpark 132 Translation BRABO II 144 Belgian Translation Centre Bremweide 106 Central fire station 127 With cooperation from Diamond District 120 Petra Panis, Jo Van de Velde, Annemie Libert, Leo Verbeke, Eveline Leemans, Ian De Bist 107 Coomans, Katrijn Apostel, Karina Rooman, Pieter Dierckx, David Van Proeyen, Kris Den Bell 133 Peeters, Cindy Broeckaert, Sacha Jennis, Klaas Meesters, Frederik Picard, Kathleen EcoHuis 143 Wens, Dorien Vanderhenst, Ivan Demil, Ilse Peleman, Liesbeth Lanneau, Kitty Haine, Eendrachtstraat 93 Tinne Buelens, Filip Pittillion, Filip Smits, Philippe Teughels, Heidi Vandenbroecke, Familiestraat 92 Greet De Roey, Joke Van haecke, Ellen Lamberts, Geert Troucheau, Anke De Geest, FelixArchief 131 Iris Gommers, Peter De Pauw, Johan Veeckman, Greet Donckers, Anne Schryvers, Gravenhof 85, 120 Dirk Van Regenmortel, Saskia Goossens, Stephanie D’hulst Antwerpen-haven Ekeren Groen Kwartier 84 Groen Zuid 85 Maps Pieter Beck Handelsstraat 92 Hof De Bist 120 Antwerpen-Luchtbal Images Hollebeekvallei 112 © City of Antwerp unless specified otherwise Investing in Europark 124 LIVAN 145 Merksem Layout -

Campenon Bernard Sge Management Team 2

1998 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CAMPENON BERNARD SGE MANAGEMENT TEAM 2 EDITORIAL 3 KEY FIGURES 4 INTERNATIONAL 6 BUILDING 8 Building export 10 Germany 14 Île-de-France 18 Rhône-Alpes, Auvergne, Bourgogne, Franche-Comté 20 Provence, Alpes, Côte d’Azur 22 CIVIL ENGINEERING 24 International division 26 Civil engineering export 28 Civil engineering France 30 Earthworks 32 Specialised works 34 NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF THE MAIN SUBSIDIARIES 36 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 39 THE MANAGEMENT TEAM SENIOR MANAGEMENT HEADS OF OPERATING DIVISIONS Henri Stouff Patrick Alvergne Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Provence, Alpes, Côte d’Azur Bernard Bonnet Guy-Jacques Barlet Vice-President Civil Engineering France Pierre Linden Renaud Bentegeat Vice-President Building Île-de-France Bernard Lozé Michel Bernard Vice-President Deputy, Civil Engineering Export Jean-Etienne Treffandier Raoul Dessaigne Vice-President Brüggemann, OBAG, UBG Charles Lénès International FUNCTIONAL DIRECTORS Jean-Marc Médio Olivier Caplain Special Works Technical Director Jacques Mimran Pierre Coppey Earthworks Director of Communication Christophe Pélissié du Rausas Jean-Marie Lambert Civil Engineering Export Director of Human Resources Yves Périllat Christian Simon Rhônes-Alpes, Auvergne, Financial Director Bourgogne, Franche-Comté Arnaud Vercken Michael Schmieder Company Secretary Klee Jean Volff Building Export 2 EDITORIAL 1998 was not only Persistently slim profit margins, even though there a year of transition was something of a recovery in building, the cut- on civil engineering back of public sector investment in France and the and building mar- collapse of accessible markets in Asia have all led kets, it was also a us to anticipate a further downturn in sales of year of far-reaching around 5% in 1999 and workforce reductions reorganisation of about 8%.