Performing the Singapore State 1988-1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Anne-Sophie Adelys

by Anne-Sophie Adelys © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 3 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz My name is Anne-Sophie Adelys. I’m French and have been living in New Zealand since 2001. I’m an artist. A painter. Each week I check “The Big idea” website for any open call for artists. On Saturday the 29th of June 2013, I answered an artist call titled: “Artist for a fringe campaign on Porn” posted by the organisation: The Porn Project. This diary documents the process of my work around this project. I’m not a writer and English is not even my first language. Far from a paper, this diary only serves one purpose: documenting my process while working on ‘The Porn Project’. Note: I have asked my friend Becky to proof-read the diary to make sure my ‘FrenchGlish’ is not too distracting for English readers. But her response was “your FrenchGlish is damn cute”. So I assume she has left it as is… © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 4 4 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz The artist call as per The Big Idea post (http://www.thebigidea.co.nz) Artists for a fringe campaign on porn 28 June 2013 Organisation/person name: The Porn Project Work type: Casual Work classification: OTHER Job description: The Porn Project A Fringe Art Campaign Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, Aotearoa/New Zealand August, 2013 In 2012, Pornography in the Public Eye was launched by people at the University of Auckland to explore issues in relation to pornography through research, art and community-based action. -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

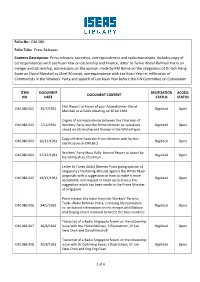

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press Releases, Speeches, Correspondences and Radio Transcripts

Folio No: DM.086 Folio Title: Press Releases Content Description: Press releases, speeches, correspondences and radio transcripts. Includes copy of correspondences with Lee Kuan Yew on citizenship and finance, letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra on merger and citizenship, submissions on the opinion made by KM Byrne on the allegations of Dr Goh Keng Swee on David Marshall as Chief Minister, correspondence with Lee Kuan Yew re: infiltration of Communists in the Workers' Party and speech of Lee Kuan Yew before the UN Committee on Colonialism ITEM DOCUMENT DIGITIZATION ACCESS DOCUMENT CONTENT NO DATE STATUS STATUS First Report to Anson of your Assemblyman David DM.086.001 30/7/1961 Digitized Open Marshall at a Public Meeting on 30 Jul 1961 Copies of correspondence between the Chairman of DM.086.002 7/12/1961 Workers' Party and the Prime Minister re: questions Digitized Open raised on citizenship and finance in the White Paper Copy of letter from the Prime Minister with further DM.086.003 16/12/1961 Digitized Open clarification on DM.86.2 Workers' Party Mass Rally: Second Report to Anson by DM.086.004 17/12/1961 Digitized Open David Marshall, Chairman Letter to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra giving opinion of Singapore's hardening attitude against the White Paper proposals with a suggestion on how to make it more DM.086.005 19/12/1961 Digitized Open acceptable, and request to meet up to discuss this suggestion which has been made to the Prime Minister of Singapore Press release of a letter from the Workers' Party to Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra, enclosing -

KLAS Art Auction 2014 Malaysian Modern & Contemporary Art Edition XI

Lot 36, Abdul Latiff Mohidin Mindscape - 27, 1983 KLAS Art Auction 2014 Malaysian modern & contemporary art Edition XI Auction Day Sunday, September 28, 2014 1.00 pm Registration & Brunch Starts 11.30 am Artworks Inspection From 11.30 am onwards Nexus 3 Ballroom, Level 3A Connexion@Nexus No 7, Jalan Kerinchi Bangsar South City 59200 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Lot 65, Ong Kim Seng Himalayan Panorama, 1982 2 3 Lot 64, Lim Tze Peng Thian Hock Keng Temple, Circa 1970s KL Lifestyle Art Space c/o Mediate Communications Sdn Bhd 150, Jalan Maarof Bukit Bandaraya 59100 Kuala Lumpur t: +603 20932668 f: +603 20936688 e: [email protected] Contact Information Auction enquiries and condition report Lydia Teoh +6019 2609668 [email protected] Datuk Gary Thanasan [email protected] Bidder registration and telephone / absentee bid Lydia Teoh +6019 2609668 [email protected] Shamila +6019 3337668 [email protected] Payment and collection Shamila +6019 3337668 [email protected] Lot 78, Ibrahim Hussein, Datuk Untitled, 1974 Kuala Lumpur Full Preview Date: September 11 - September 27, 2014 Venue: KL Lifestyle Art Space 150, Jalan Maarof Bukit Bandaraya 59100 Kuala Lumpur Auction Day Date: Sunday, September 28, 2014 Venue: Nexus 3 Ballroom, Level 3A Connexion@Nexus No 7, Jalan Kerinchi Bangsar South City 59200 Kuala Lumpur Time: 1.00 pm Map to Connexion@Nexus 7 Lot 77, Abdullah Ariff Chinese Junk, 1956 Contents 7 Auction Information 10 Glossary 18 Lot 1 - 77 149 Auction Terms and Conditions 158 Index of Artists Lot 37, Yusof Ghani Siri Tari, 1989 Glossary 6 BASOEKI ABDULLAH 1 AWANG DAMIT AHMAD Indonesian WomAn in Red, 2006 Iraga Dayung Patah, 2006 Oil on canvas | 69 x 50 cm Mixed media on canvas | 100 x 101 cm RM 35,000 - RM 45,000 RM 8,000 - RM 18,000 2 TAJUDDIN ISMAIL 7 JEIHAN SUKMANTORO Magenta Landscape, 2001 Miryam, 1997 Acrylic and pastel on board | 61 x 60 cm Oil on canvas | 70 x 70 cm RM 3,000 - RM 8,000 RM 7,000 - RM 12,000 3 Ismail Latiff 8 HAN SNEL Angkasa Mandi Angin No. -

Exhibition Guide

ArTScience MuSeuM™ PreSenTS ceLeBrATinG SinGAPOre’S cOnTeMPOrArY ArT Exhibition GuidE Detail, And We Were Like Those Who Dreamed, Donna Ong Open 10am to 7pm daily | www.MarinaBaySands.com/ArtScienceMuseum Facebook.com/ArtScienceMuseum | Twitter.com/ArtSciMuseum WELCOME TO PRUDENTIAL SINGAPORE EYE Angela Chong Angela chong is an installation artist who Prudential Singapore Eye presents a with great conceptual confidence. uses light, sound, narrative and interactive comprehensive survey of Singapore’s Works range across media including media to blur the line between fiction and contemporary art scene through the painting, installation and photography. reality. She has shown work in Amsterdam Light Festival in the netherlands; Vivid works of some of the country’s most The line-up includes a number of Festival in Sydney; 100 Points of Light Festival innovative artists. The exhibiting artists who are gaining an international in Melbourne; cP international Biennale in artists were chosen from over 110 following, to artists who are just Jakarta, indonesia, and iLight Marina Bay in submissions and represent a selection beginning to be known. Like all the other Singapore. of the best contemporary art in Prudential Eye exhibitions, Prudential 3D Tic-Tac-Toe is an interactive light sculpture Singapore. Prudential Singapore Eye is Singapore Eye aims to bring to light which allows multiple players of all ages to the first major exhibition in a year of a new and exciting contemporary art play Tic-Tac-Toe with one another. cultural celebrations of the nation’s 50th scene and foster greater appreciation of anniversary. Singapore’s visual art scene both locally and internationally. 3D Tic-Tac-Toe, 2014 The works of the exhibiting artists demonstrate versatility, with many of the artists working experimentally Jeremy Sharma Jeremy Sharma works primarily as a conceptual painter. -

PDF (Digitised by BL Ethos Service)

Durham E-Theses The formation of identities and art museum education: the Singapore case Leong, Wai Yee Jane How to cite: Leong, Wai Yee Jane (2009) The formation of identities and art museum education: the Singapore case, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1347/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ano Iq/Durham uºYivet"sity The Formation of Identities and Art Museum Education: The Singapore Case The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. Leong Wai Yee Jane A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Education School of Education University of Durham, U. -

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Singapore: the Location of Choice for Asset and Wealth Management in Asia Pacific

Singapore: the location of choice for asset and wealth management in Asia Pacific Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet 2 | PwC Contents Singapore as a location for asset managers 4 Singapore’s asset management landscape 12 Fund manager regime in Singapore 16 Investment funds in Singapore 21 Singapore market entry report 28 Asian investment fund centre 31 Connect with our experts 32 Singapore - Asset and Wealth management location of choice in Asia Pacific | 3 Singapore as a location for asset managers 4 | PwC Introducing Singapore A global business hub Singapore is strategically located the heart of Southeast The USD-SGD exchange rate has remained largely Asia. The country is 724 square kilometers, or 280 square stable over the last ten years, trading in the band of miles. Whilst smaller than other financial centres like 1.2 - 1.45. London, New York, or Hong Kong, it’s small size is no Having a small and open economy, Singapore’s impediment to its role as a global asset and wealth monetary policy has thus been centered on the management centre. management of the exchange rate, with the primary With a population of 5.8 million in 2019, one of Singapore’s objective of promoting medium term price stability as a strengths is its diverse population. Comprising three main sound basis for sustainable economic growth. ethnic groups and cultures, with smaller ones interspersed These are essential factors that enhance the ecosystem across the community, Singapore’s workforce is able to and economical support of Singapore as a choice communicate culturally and linguistically with the key location for setting up fund management operations markets of China and India, as well as engaging on the focused on investments in Asia, particularly in India and global scale. -

SPAFA Digest 1990, Vol 11, No. 3

39 (Symbolic Communication in Theatre: A Malaysian Chinese Case by Dr. Chua Soo Pong Theatrical event in Asian Examination of the details of the feelings of the Chinese community in societies has never been a purely structural processes in the artistic Malaysia. But they also reflect the artistic event. It usually has several production of the arts could locate awareness of the Chinese artistes in functions simultaneously. Subli in the specific issues in the wider social stating their inspiration to promote Philippines, Wayang Purwa in Java, context. Malay, Indian, and Chinese dance on Chinese opera in Singapore, Mayong This paper is based on personal equal footing. It is clear that the in Kelantan, or Lakorn Chatri in involvement as adjudicator in the Chinese artistes would prefer the art Thailand, all demonstrate the fact four dance festivals (1983, 1984, 1987, forms of the various ethnic groups to that theatrical events in the region 1989) organized by a number of be developed side by side with one serve a variety of political, social or Chinese cultural organizations in another. religious purposes much more expli- Malaysia and in the author's long citly than the art forms in the West. time observations and research on Gathering in Penang Anthropologists of the art and dance in Malaysia. In this article expressive culture have in recent years the author will focus on three areas. The last two days of 1983 have advanced their studies and proposed It provides an overview of the been most exciting for the dance several approaches in the analysis of festivals organized in the last few audience in Penang. -

Nhb13093018.Pdf

Annual Report 2012/2013 CONTENTS 2 Highlights for FY2012 14 Board Members 16 Corporate Information 17 Organisational Structure 18 Corporate Governance 20 Grants & Capability Development 24 Giving 32 Donations & Acquisitions 38 Publications FY2012 was an exciting year of new developments. On 1 November 2012, we came under a new ministry – the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth. Under the new ministry, we aspire 40 Financial Statements to deepen our conversations and engagements with various sectors. We will continue to nurture Statement by Board Members an appreciation for Singapore’s diverse and multicultural heritage and provide platforms for Independent Auditors’ Report community involvement. Financials A new family member, the Language Council joined the NHB family and we warmly welcome Notes to Financial Statements them. Language is closely linked to one’s heritage and the work that the LCS does will allow NHB to be more synergistic in our heritage offerings for Singaporeans. In FY2012, we launched several new initiatives. Of particular significance was the launch of Our Museum @ Taman Jurong – the first community museum in Singapore’s heartlands. The Malay Heritage Centre was re-opened with a renewed focus on Kampong Gelam, and the contributions of the local Malay community. The Asian Civilisations Museum also announced a new extension, which will allow for more of our National Collection to be displayed. Community engagement remained a priority as we stepped up our efforts to engage Singaporeans from all walks of life – heritage enthusiasts, corporations, interest groups, volunteer guides, patrons and many more, joined us in furthering the heritage cause. Their stories and memories were shared and incorporated into a wide range of offerings including community exhibitions and events, heritage trails, merchandise and e-books.