Artistic Codemixing. Michael D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Enrique Iglesias' “Duele El Corazon” Reaches Over 1 Billion Cumulative Streams and Over 2 Million Downloads Sold Worldwide

ENRIQUE IGLESIAS’ “DUELE EL CORAZON” REACHES OVER 1 BILLION CUMULATIVE STREAMS AND OVER 2 MILLION DOWNLOADS SOLD WORLDWIDE RECEIVES AMERICAN MUSIC AWARD FOR BEST LATIN ARTIST (New York, New York) – This past Sunday, global superstar Enrique Iglesias wins the American Music Award for Favorite Latin Artist – the eighth in his career and the most by any artist in this category. The award comes on the heels of a whirlwind year for Enrique. His latest single, “DUELE EL CORAZON” has shattered records across the globe. The track (click here to listen) spent 14 weeks at #1 on the Hot Latin Songs chart, held the #1 spot on the Latin Pop Songs chart for 10 weeks and has over 1 billion cumulative streams and over 2 million tracks sold worldwide. The track also marks Enrique’s 14th #1 on the Dance Club Play chart, the most by any male artist. He also holds the record for the most #1 debuts on Billboard’s Latin Airplay chart. In addition to his recent AMA win, Enrique also took home 5 awards at this year’s Latin American Music Awards for Artist of the Year, Favorite Male Pop/Rock Artist and Favorite Song of the Year, Favorite Song Pop/Rock and Favorite Collaboration for “DUELE EL CORAZON” ft. Wisin. Earlier this month, Enrique went to France to receive the NRJ Award of Honor. For the past two years, Enrique has been touring the world on his SEX AND LOVE Tour which will culminate in Prague, Czech Republic on December 18th. Remaining 2016 Tour Dates Nov. -

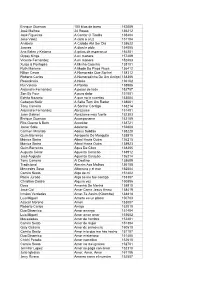

Spanish NACH INTERPRET

Enrique Guzman 100 kilos de barro 152009 José Malhoa 24 Rosas 136212 José Figueiras A Cantar O Tirolês 138404 Jose Velez A cara o cruz 151104 Anabela A Cidade Até Ser Dia 138622 Juanes A dios le pido 154005 Ana Belen y Ketama A gritos de esperanza 154201 Gypsy Kings A mi manera 157409 Vicente Fernandez A mi manera 152403 Xutos & Pontapés A Minha Casinha 138101 Ruth Marlene A Moda Do Pisca Pisca 136412 Nilton Cesar A Namorada Que Sonhei 138312 Roberto Carlos A Namoradinha De Um Amigo M138306 Resistência A Noite 136102 Rui Veloso A Paixão 138906 Alejandro Fernandez A pesar de todo 152707 Son By Four A puro dolor 151001 Ednita Nazario A que no le cuentas 153004 Cabeças NoAr A Seita Tem Um Radar 138601 Tony Carreira A Sonhar Contigo 138214 Alejandro Fernandez Abrazame 151401 Juan Gabriel Abrazame muy fuerte 152303 Enrique Guzman Acompaname 152109 Rita Guerra & Beto Acreditar 138721 Javier Solis Adelante 152808 Carmen Miranda Adeus Solidão 138220 Quim Barreiros Aeroporto De Mosquito 138510 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 136215 Mónica Sintra Afinal Havia Outra 138923 Quim Barreiros Água De Côco 138205 Augusto César Aguenta Coração 138912 José Augusto Aguenta Coração 136214 Tony Carreira Ai Destino 138609 Tradicional Alecrim Aos Molhos 136108 Mercedes Sosa Alfonsina y el mar 152504 Camilo Sesto Algo de mi 151402 Rocio Jurado Algo se me fue contigo 153307 Christian Castro Alguna vez 150806 Doce Amanhã De Manhã 138910 José Cid Amar Como Jesus Amou 138419 Irmãos Verdades Amar-Te Assim (Kizomba) 138818 Luis Miguel Amarte es un placer 150703 Azucar -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Accord

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON TARIFFS AND TRADE MIN(86)/INF/3 ACCORD GENERAL SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ET LE COMMERCE 17 September 1986 ACUERDO GENERAL SOBRE ARANCELES ADUANEROS Y COMERCIO Limited Distribution CONTRACTING PARTIES PARTIES CONTRACTANTES PARTES CONTRATANTIS Session at Ministerial Session à l'échelon Periodo de sesiones a nivel Level ministériel ministerial 15-19 September 1986 15-19 septembre 1986 15-19 setiembre 1986 LIST OF REPRESENTATIVES LISTE DES REPRESENTANTS LISTA DE REPRESENTANTES Chairman: S.E. Sr. Enrique Iglesias Président; Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores Présidente; de la Republica Oriental del Uruguay ARGENTINA Représentantes Lie. Dante Caputo Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto » Dr. Juan V. Sourrouille Ministro de Economia Dr. Roberto Lavagna Secretario de Industria y Comercio Exterior Ing. Lucio Reca Secretario de Agricultura, Ganaderïa y Pesca Dr. Bernardo Grinspun Secretario de Planificaciôn Dr. Adolfo Canitrot Secretario de Coordinaciôn Econômica 86-1560 MIN(86)/INF/3 Page 2 ARGENTINA (cont) Représentantes (cont) S.E. Sr. Jorge Romero Embajador Subsecretario de Relaciones Internacionales Econômicas Lie. Guillermo Campbell Subsecretario de Intercambio Comercial Dr. Marcelo Kiguel Vicepresidente del Banco Central de la Republica Argentina S.E. Leopoldo Tettamanti Embaj ador Représentante Permanante ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra S.E. Carlos H. Perette Embajador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la Republica Oriental del Uruguay S.E. Ricardo Campero Embaj ador Représentante Permanente de la Republica Argentina ante la ALADI Sr. Pablo Quiroga Secretario Ejecutivo del Comité de Politicas de Exportaciones Dr. Jorge Cort Présidente de la Junta Nacional de Granos Sr. Emilio Ramôn Pardo Ministro Plenipotenciario Director de Relaciones Econômicas Multilatérales del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto Sr. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

03.12.13 GGB Master Set List.Xlsx

GGB MASTER SET LIST Name Artist Alone Heart Babe I'm gonna leave you Gina Glocksen Band Bad U2 Barely Gina Glocksen Before He Cheats Carrie Underwood Betterman Pearl Jam Blister in the Sun Violent Femmes Blown Away Carrie Underwood Can't Help Falling In Love With You Elvis Presley Crazy Train Ozzy Osbourne Dammit blink-182 Dream On Aerosmith Drink In My Hand Eric Church Eleanor Rigby Gina Glocksen Band Everlong Foo Fighters Everybody Talks Neon Trees Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash Forget You Cee Lo Green Gunpowder & Lead Miranda Lambert Harder to Breathe Maroon 5 Hemorrhage Fuel Hey Jude The Beatles Higher Ground Red Hot Chili Peppers Ho Hey The Lumineers Hot Stuff Donna Summer Hurt Gina Glocksen I'll Stand By You Pretenders I Knew You Were Trouble Taylor Swift I Think We're Alone Now Tiffany I Want You to Want Me Cheap Trick I Will Wait Mumford & Sons I Wish Stevie Wonder Interstate Love Song Stone Temple Pilots Jack & Diane John Mellencamp Landslide Dixie Chicks Let's Get It On Marvin Gaye Lightning Crashes Live Man in the Box Alice In Chains Mary Jane's Last Dance Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers Misery Business Paramore Mr. Brownstone Guns N' Roses Name Artist My Own Worst Enemy Lit Never Gonna Give You Up Rick Astley Old Dance Medley Gina Glocksen Band The Only Exception Paramore Over the Hills and Far Away Led Zeppelin Paradise City Guns N' Roses Piece of My Heart Janis Joplin Play That Funky Music Wild Cherry Pour Some Sugar on Me Def Leppard Livin' on a Prayer Bon Jovi Pride (In the Name of Love) U2 Raise Your Glass Pink Red Solo Cup Toby Keith Redneck Woman Gretchen Wilson Rihanna Medley Gina Glocksen Band Satellite Dave Matthews Band Say It Ain't So Weezer Shimmer Fuel Shine Collective Soul Shout The Isley Brothers (Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay Sara Bareilles Spiderwebs No Doubt Stars Grace Potter & The Nocturnals The Story Brandi Carlile Stranglehold Ted Nugent Stuck like glue Gina Glocksen Band Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 Superhero Gina Glocksen Sweet Child O' Mine Guns N' Roses T.N.T. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

Communiqué De Presse Maroc Telecom Lance Le Forfait Universal

Communiqué de presse Rabat, le 03 décembre 2010 Maroc Telecom lance le Forfait Universal Music 60 minutes de communication, 300 SMS / MMS, l’accès exclusif et illimité un catalogue riche et inédit de vidéos clips Universal Music et aux 4 chaînes de télévision MTV, le tout à 99 DH, c’est le nouveau Forfait de Maroc Telecom pour les jeunes. Le Forfait Universal Music est le fruit d’un partenariat entre Maroc Telecom, Universal Music, leader mondial de la musique et pionnier de la distribution musicale numérique et MTV (Music Television), chaîne de télévision spécialisée dans la diffusion des vidéo-clips musicaux. Visionner sur leur mobile les contenus vidéos clips sans cesse renouvelés et enrichis du catalogue d’Universal Music, accéder aux 4 chaînes du bouquet MTV, rester en contact avec leurs parents et leurs proches grâce à 60 minutes de communications valables vers toutes les destinations nationales et internationales** et à 300 SMS / MMS vers tous les opérateurs nationaux, c’est tout cela à la fois que Maroc Telecom offre aux jeunes en un seul forfait, pour 99 DH seulement. Pour leur permettre de profiter pleinement du forfait Universal Music Mobile, Maroc Telecom met à leur disposition une large gamme de terminaux à partir de 0 DH*. Ils pourront également participer à des animations et des jeux concours dédiés et bénéficier gratuitement des services de transfert et de réception d’argent sur mobile, Mobicash. L’offre Forfait Universal Music, bâtie sur des savoir-faire complémentaires, reflète la volonté de Maroc Telecom de satisfaire toujours mieux les attentes d’une clientèle jeune, avide de communication et de nouveaux contenus mais soucieuse de maîtriser son budget. -

Después De 17 Años, Todo Indica Que Enrique Iglesias Dejará Su Cargo

PRESIDENCIA+BID La sucesión POR LUCY CONGER AY CONSENSO. PERO en el BID ¿habrá consenso? Se Después de 17 años, todo indica que avecina una elección en el Banco Intera- Enrique Iglesias dejará su cargo este año. mericano de Desa- ¿Quiénes son los candidatos a sucederle? Hrrollo para seleccionar a quien será el presidente que suceda al veterano Enrique Iglesias. ¿Veremos una divi- Andina de Fomento (CAF) desde 1991; mocionó como su candidato durante sión como la que surgió en la reciente Luis Alberto Moreno, Embajador de la Cumbre Ibero-americana en San elección en la OEA? Colombia en Washington desde hace José, Costa Rica, en noviembre del año Hasta ahora, hay consenso en la casi siete años, y João Sayad, el vice- pasado. Sin embargo, los funcionarios especulación sobre los candidatos presidente de Planeamiento y Admi- colombianos contactados por PODER para suceder a Iglesias, quien acaba nistración del BID desde septiembre no quisieron confirmar la postulación de marcar un récord en la presidencia de 2004. Claro, estas candidaturas de Moreno mientras Iglesias continúe del BID, al cumplir 17 años al frente no son ni anunciadas ni confirma- en la presidencia. de la entidad. Los candidatos para das, pero son los nombres barajados Por razones obvias, algo semejan- quedar al frente del banco multilate- en Washington entre una gama de te ocurre con Iglesias, de 74 años, un ral que más presta a América Latina fuentes muy bien informadas. consumado diplomático que fue can- son, en cuidadoso orden alfabético En realidad, la de Moreno ha sido ciller de Uruguay entre 1985 y 1988, (por nombre y no por país): Enrique una candidatura “anunciada” desde antes de ser electo para presidir el García, presidente de la Corporación que el presidente Álvaro Uribe lo pro- banco. -

2016 CCD Ourglass

Community College of Denver Student Literary & Art Magazine 2015 & 2016 Community College of Denver Student Literary & Art Magazine 2015 & 2016 Hi! Ourglass, now in its 36th year of publication, is the journal of the English, Graphic Design, and Visual Arts departments at Community College of Denver, dedicated to providing a forum for the poetry, prose, drama, design, and artwork of our students. Please consider submitting your work to Ourglass. If you are attending CCD or have attended in the past, you are eligible to submit. Submissions are accepted between September 15th and March 24th of each year. We accept submissions of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, drama, and artwork, as well as any interesting combinations thereof, exclusively through our email address: [email protected]. All work submitted must include your name, phone number and current email address. Submit one story or essay at a time; poems can be sent in groups. Send in only low-resolution copies of artwork; we will contact you for high-resolution versions at a later time. Due to the sheer volume of work we must consider, we can only notify you if your work is chosen to be published. If you don’t hear from us, please do try again next year! We love hearing from CCD students and alumni. Follow US! Facebook | Facebook.com/CCDOurglass Twitter | Twitter.com/OurglassCCD If you have any questions, please email us at [email protected]. Thanks, The Editors Poetry & Prose Harmony Sheehan Gemini 1 Harmony Sheehan What They Don’t Tell You 4 Claudia Graham Kaleidoscope Eyes 5 Amber Dorr The Problem with Soulmates 11 Kelly Kracke Muses pt. -

The Object Who Knew Too Much Donald Kunze

The Object Who Knew Too Much Donald Kunze Pere Borrell del Caso, Escapando de la crítica (Escaping Criticism), 1874. The painter's products stand before us as though they were alive, but if you question them, they maintain a most majestic silence. It is the same with written words; they seem to talk to you as if they were intelligent, but if you ask them anything about what they say, from a desire to be instructed, they go on telling you just the same thing forever [emphasis mine]. ——Plato, Phædrus, 275d When objects speak to us, they engage poetic mentality that uses frames and exchanges across frames to construct a “boundary language.” Modern rhetorical theory generally assigns such actions to the figure of ekphrasis, but a more specific definition is needed. What is inside the frame “signals” to The Object Who Knew Too Much 1 us in a conventionalized way; but passage across and within framed spaces must shift to a new channel of communication. Although the art object must travel along smugglers’ trails by night and use special codes to “signalize” to us, the subjects–who–see, this signalizing constructs new channels in space and time. The covert message cannot be experienced in a detached way. The object in art engages the subject in sheer immediacy. This is the power of ekphrasis. We can imagine a shamanistic origin for this “here and now” function, where natural and specially constructed objects are empowered to speak a voix acousmatique, in codes and channels designated as permanently authentic. We already allow that art has a basic, native ekphrastic power: after all, poetry is sung to the heart, architecture is, naturally, architecture parlant. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question