OUGS Journal 28(1) © Copyright Reserved Email: [email protected] Spring Edition 2007 Cover Illustration: Thin Sections of Several Different Habits of Barite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

2002 New Zealand Botanical Society

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 67 MARCH 2002 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Anthony Wright Secretary/Treasurer: Doug Rogan Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 Subscriptions The 2002 ordinary and institutional subscriptions are $18 (reduced to $15 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 2002 student subscription, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28th February each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next years subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the June 2002 issue (68) is 25 May 2002. Please post contributions to: Joy Talbot 23 Salmond Street Christchurch 8002 Send email contributions to [email protected] Files can be in WordPerfect (version 8 or earlier), MS Word (Word 97 or earlier) or saved as RTF or ASCII. -

Moutere Gravels

LAND USE ON THE MOUTERE GRAVELS, I\TELSON, AND THE DilPORTANOE OF PHYSIC.AL AND EOONMIC FACTORS IN DEVJt~LOPHTG THE F'T:?ESE:NT PATTERN. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS ( Honours ) GEOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF NEW ZEALAND 1953 H. B. BOURNE-WEBB.- - TABLE OF CONTENTS. CRAFTER 1. INTRODUCTION. Page i. Terminology. Location. Maps. General Description. CH.AFTER 11. HISTORY OF LAND USE. Page 1. Natural Vegetation 1840. Land use in 1860. Land use in 1905. Land use in 1915. Land use in 1930. CHA.PrER 111. PRESENT DAY LAND USE. Page 17. Intensively farmed areas. Forestry in the region. Reversion in the region. CHA.PrER l V. A NOTE ON TEE GEOLOGY OF THE REGION Page 48. Geological History. Composition of the gravels. Structure and surface forms. Slope. Effect on land use. CHA.mm v. CLIMATE OF THE REGION. Page 55. Effect on land use. CRAFTER Vl. SOILS ON Tlffi: MGm'ERE GRAVELS. Page 59. Soil.tYJDes. Effect on land use. CHAPrER Vll. ECONOMIC FACTORS WrIICH HAVE INFLUENCED TEE LAND USE PATTERN. Page 66. ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS. ~- After page. l. Location. ii. 2. Natu.ral Vegetation. i2. 3. Land use in 1905. 6. Land use regions and generalized land use. 5. Terraces and sub-regions at Motupiko. 27a. 6. Slope Map. Folder at back. 7. Rainfall Distribution. 55. 8. Soils. 59. PLATES. Page. 1. Lower Moutere 20. 2. Tapawera. 29. 3. View of Orcharding Arf;;a. 34a. 4. Contoured Orchard. 37. 5. Reversion and Orchards. 38a. 6. Golden Downs State Forest. 39a. 7. Japanese Larch. 40a. B. -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material S1 Eruptions considered Askja 1875 Askja, within Iceland’s Northern Volcanic Zone (NVZ), erupted in six phases of varying intensity, lasting 17 hours on 28–29 March 1875. The main eruption included a Subplinian phase (Unit B) followed by hydromagmatic fall and with some proximal pyroclastic flow (Unit C) and a magmatic Plinian phase (Unit D). Units C and D consisted of 4.5 x 108 m3 and 1.37 x 109 m3 of rhyolitic tephra, respectively [1–3]. Eyjafjallajökull 2010 Eyjafjallajökull is situated in the Eastern Volcanic Zone (EVZ) in southern Iceland. The Subplinian 2010 eruption lasted from 14 April to 21 May, resulting in significant disruption to European airspace. Plume heights ranged from 3 to 10 km and dispersing 2.7 x 105 m3 of trachytic tephra [4]. Hverfjall 2000 BP Hverfjall Fires occurred from a 50 km long fissure in the Krafla Volcanic System in Iceland’s NVZ. Magma interaction with an aquifer resulted in an initial basaltic hydromagmatic fall deposit from the Hverfjall vent with a total volume of 8 x 107 m3 [5]. Eldgja 10th century The flood lava eruption in the first half of the 10th century occurred from the Eldgja fissure within the Katla Volcanic System in Iceland’s EVZ. The mainly effusive basaltic eruption is estimated to have lasted between 6 months and 6 years, and included approximately 16 explosive episodes, both magmatic and hydromagmatic. A subaerial eruption produced magmatic Unit 7 (2.4 x 107 m3 of tephra) and a subglacial eruption produced hydromagmatic Unit 8 (2.8 x 107 m3 of tephra). -

Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 Pp. Donovan, B. J. 2007

Donovan, B. J. 2007: Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 pp. EDITORIAL BOARD REPRESENTATIVES OF L ANDCARE R ESEARCH Dr D. Choquenot Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Dr R. J. B. Hoare Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF UNIVERSITIES Dr R.M. Emberson c/- Bio-Protection and Ecology Division P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF M USEUMS Mr R.L. Palma Natural Environment Department Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF OVERSEAS I NSTITUTIONS Dr M. J. Fletcher Director of the Collections NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit Forest Road, Orange NSW 2800, Australia * * * SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 57 Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) B. J. Donovan Donovan Scientific Insect Research, Canterbury Agriculture and Science Centre, Lincoln, New Zealand [email protected] Manaaki W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2007 4 Donovan (2007): Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2007 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Cataloguing in publication Donovan, B. J. (Barry James), 1941– Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) / B. J. Donovan – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, 2007. (Fauna of New Zealand, ISSN 0111–5383 ; no. -

Nzbotsoc No 83 March 2006

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 83 MARCH 2006 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Anthony Wright Secretary/Treasurer: Ewen Cameron Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 Subscriptions The 2006 ordinary and institutional subscriptions are $25 (reduced to $18 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 2006 student subscription, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28th February each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next years subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the June 2006 issue is 28 May 2006. Please post contributions to: Joy Talbot 17 Ford Road Christchurch 8002 Send email contributions to [email protected] or [email protected]. Files are preferably in MS Word (Word XP or earlier) or saved as RTF or ASCII. -

The-Pembrokeshire-Marine-Code.Pdf

1 Skomer Island 2 South Pembrokeshire (Area 1) 4 Ramsey Island 100m from island P MOD Danger Area Caution Stack Rocks sensitive area for cetaceans Caution Caution porpoise sensitive area sensitive area for cetaceans Harbour (N 51 deg 44.36’ W 5 deg 16.88’) 3 South Pembrokeshire (Area 2) You are welcome to land on Skomer in North Haven You are more likely to (on the right hand beach as you approach from encounter porpoise 1hr the sea) GR 735 095. Access up onto the Island is Access to either side of slack between 10am and 6pm every day except Mondays, Wick allowed Skomer Marine Nature Reserve water. Extra caution (bank holidays excluded). It’s free if you remain on during August only required in this the beach, £6 landing fee payable for access onto Broad Haven Beach area at these the Island. Please find a member of staff for an times introductory talk and stay on the paths to avoid the P puffin burrows. Skomer Warden: 07971 114302 Stackpole Head Church Rock 5 St Margarets & Caldey Island 6 The Smalls Access: Caldey is a private island owned by the Reformed Cistercian Community. Boat owners are reminded that landing on Caldey from craft Extreme caution other than those in the Caldey highly sensitive Pool is not permitted. Access may be granted on special porpoise area occasions by pre-arrangement. 100m from island T 01834 844453 minimum safe 8 Grassholm 11 Strumble Head navigable speed only, Access to Grassholm is on south going tide. restricted due to the island 7 Skokholm Island being the worlds third largest Caution gannet colony (RSPB). -

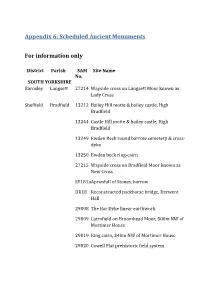

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Explosive Subaqueous Eruptions: the Influence of Volcanic Jets on Eruption Dynamics and Tephra Dispersal in Underwater Eruptions

EXPLOSIVE SUBAQUEOUS ERUPTIONS: THE INFLUENCE OF VOLCANIC JETS ON ERUPTION DYNAMICS AND TEPHRA DISPERSAL IN UNDERWATER ERUPTIONS by RYAN CAIN CAHALAN A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Earth ScIences and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon In partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy December 2020 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ryan CaIn CahaLan Title: ExplosIve Subaqueous EruptIons: The Influence of Volcanic Jets on EruptIon DynamIcs and Tephra DIspersaL In Underwater EruptIons This dissertatIon has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Doctor of PhiLosophy degree in the Department of Earth ScIences by: Dr. Josef Dufek ChaIrperson Dr. Thomas GIachettI Core Member Dr. Paul WaLLace Core Member Dr. KeLLy Sutherland InstItutIonaL RepresentatIve and Kate Mondloch Interim VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2020 II © 2020 Ryan Cain Cahalan III DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Ryan CaIn CahaLan Doctor of PhiLosophy Department of Earth ScIences December 2020 Title: ExplosIve Subaqueous EruptIons: The Influence of Volcanic Jets on EruptIon DynamIcs and Tephra DIspersaL In Underwater EruptIons Subaqueous eruptIons are often overlooked in hazard consIderatIons though they represent sIgnificant hazards to shipping, coastLInes, and in some cases, aIrcraft. In explosIve subaqueous eruptIons, volcanic jets transport fragmented tephra and exsolved gases from the conduit into the water column. Upon eruptIon the volcanic jet mIxes wIth seawater and rapidly cools. This mIxing and assocIated heat transfer ultImateLy determInes whether steam present in the jet wILL completeLy condense or rise to breach the sea surface and become a subaeriaL hazard. -

New Zealand National Climate Summary 2011: a Year of Extremes

NIWA MEDIA RELEASE: 12 JANUARY 2012 New Zealand national climate summary 2011: A year of extremes The year 2011 will be remembered as one of extremes. Sub-tropical lows during January produced record-breaking rainfalls. The country melted under exceptional heat for the first half of February. Winter arrived extremely late – May was the warmest on record, and June was the 3 rd -warmest experienced. In contrast, two significant snowfall events in late July and mid-August affected large areas of the country. A polar blast during 24-26 July delivered a bitterly cold air mass over the country. Snowfall was heavy and to low levels over Canterbury, the Kaikoura Ranges, the Richmond, Tararua and Rimutaka Ranges, the Central Plateau, and around Mt Egmont. Brief dustings of snow were also reported in the ranges of Motueka and Northland. In mid-August, a second polar outbreak brought heavy snow to unusually low levels across eastern and alpine areas of the South Island, as well as to suburban Wellington. Snow also fell across the lower North Island, with flurries in unusual locations further north, such as Auckland and Northland. Numerous August (as well as all-time) low temperature records were broken between 14 – 17 August. And torrential rain caused a State of Emergency to be declared in Nelson on 14 December, following record- breaking rainfall, widespread flooding and land slips. Annual mean sea level pressures were much higher than usual well to the east of the North Island in 2011, producing more northeasterly winds than usual over northern and central New Zealand. -

No 88, 18 November 1931, 3341

~umb. 88. 3341 SUPPLEMENT TO THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE OF THURSDAY. NOVEMBER 12, 1931. WELLINGTON, WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 18, 1931. TY1'its for Election of Members of Pw·liament. [L.S.] BLEDISLOE, Governor-General. A PROCLAJI.'IATION. To ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN: GREETING. KNOW ye that J, Charles, Ba.ron Bledisloe, the Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, being desirous that the General Assembly of New Zealand should be holden as soon as may be, do declare that I have this day signed my Warrant directing the Clerk of the Writs to proceed with the election of members of Parliament to serve in the House of Representatives for all the electoral districts within the said Dominion of New Zealand. Given under the hand of His Excellency the' Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, and issued under the Seal of that Dominion, this 12th day of November, 1931. GEO. W. FORBES. GOD SAVE THE KING ! 3342 THE NEW ZE~ GAZETTE. [No. 88 Returning O.fficers appointed. RegiBtrars of Electors appointed. T is hereby notified that each of the undermentioned T is hereby notified that each of the undermentioned persons I persons has been appointed. Registrar of Electors for I has been appointed Ret~ing Officer for the electoral the electoral district the name of which appears opposite district~ the name of which appears opposite his name. his name. Erwin Sharman Molony Auckland Central. Frank Evans Auckland Central. George Chetwyn Parker .. Auckland East. Frank Evans Auckland East. Edward William John Bowden Auckland Suburbs. Frank Evans Auckland Suburbs. Thomas Mitchell Crawford ., Auckland West. -

Conservation Campsites South Island 2019-20 Nelson

NELSON/TASMAN Note: Campsites 1–8 and 11 are pack in, pack out (no rubbish or recycling facilities). See page 3. Westhaven (Te Tai Tapu) Marine Reserve North-west Nelson Forest Park 1 Kahurangi Marine Takaka Tonga Island Reserve 2 Marine Reserve ABEL TASMAN NATIONAL PARK 60 3 Horoirangi Motueka Marine KAHURANGI Reserve NATIONAL 60 6 Karamea PARK NELSON Picton Nelson Visitor Centre 4 6 Wakefield 1 Mount 5 6 Richmond Forest Park BLENHEIM 67 6 63 6 Westport 7 9 10 Murchison 6 8 Rotoiti/Nelson Lakes 1 Visitor Centre 69 65 11 Punakaiki NELSON Marine ReservePunakaiki Reefton LAKES NATIONAL PARK 7 6 7 Kaikōura Greymouth 70 Hanmer Springs 7 Kumara Nelson Visitor Centre P Millers Acre/Taha o te Awa Hokitika 73 79 Trafalgar St, Nelson 1 P (03) 546 9339 7 6 P [email protected] Rotoiti / Nelson Lakes Visitor Centre Waiau Glacier Coast P View Road, St Arnaud Marine Reserve P (03) 521 1806 Oxford 72 Rangiora 73 0 25 50 km P [email protected] Kaiapoi Franz Josef/Waiau 77 73 CHRISTCHURCH Methven 5 6 1 72 77 Lake 75 Tauparikākā Ellesmere Marine Reserve Akaroa Haast 80 ASHBURTON Lake 1 6 Pukaki 8 Fairlie Geraldine 79 Hautai Marine Temuka Reserve Twizel 8 Makaroa 8 TIMARU Lake Hāwea 8 1 6 Lake 83 Wanaka Waimate Wanaka Kurow Milford Sound 82 94 6 83 Arrowtown 85 6 Cromwell OAMARU QUEENSTOWN 8 Ranfurly Lake Clyde Wakatipu Alexandra 85 Lake Te Anau 94 6 Palmerston Te Anau 87 8 Lake Waikouaiti Manapouri 94 1 Mossburn Lumsden DUNEDIN 94 90 Fairfield Dipton 8 1 96 6 GORE Milton Winton 1 96 Mataura Balclutha 1 Kaka Point 99 Riverton/ INVERCARGILL Aparima Legend 1 Visitor centre " Campsite Oban Stewart Island/ National park Rakiura Conservation park Other public conservation land Marine reserve Marine mammal sanctuary 0 25 50 100 km NELSON/TASMAN Photo: DOC 1 Tōtaranui 269 This large and very popular campsite is a great base for activities; it’s a good entrance point to the Abel Tasman Coast Track.