We Survived … at Last I Speak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'internement En France 1940-1946

PROJET ÉDUCATION DES ROMS | HISTOIRE ENFANTS ROMS COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L´EUROPE EN EUROPE L’INTERNEMENT 5.3 EN FRANCE 1940-1946 l’internement en France 1940-1946 Marie-Christine Hubert Identifier les « Tsiganes » et suivre leurs mouvements | Ordres d’assignation à résidence des « nomades » vivant sur le territoire du troisième Reich | Internement dans la zone libre | Internement dans la zone occupée | Après la Libération | Vie quotidienne dans les camps | Cas de déportation depuis les camps d’internement français En France, deux approches différentes mais parallèles coexistent concernant ce qu’il est convenu d’appeler « la question tsigane ». L’approche française consistant à recourir à l’internement afin d’intégrer les « Tsiganes » à la société majoritaire prévaut sur l’approche allemande de l’internement en tant que première phase de l’assassinat collectif. De sorte que les Roms de France, à la différence de leurs homologues des autres pays occupés par les Allemands, ne seront pas exterminés dans le camp d’Auschwitz. Toutefois, ils n’échappent pas à la persécution : des familles entières sont internées dans des camps spéciaux à travers tout le pays pendant et après l’occupation. CAMPS D’INTERNEMENT POUR « TSIGANES » INTRODUCTION EN FRANCE DURANT LA SECONDE GUERRE MONDIALE Ill. 1 Alors que dans les années 1930, en Allemagne, (par Jo Saville et Marie-Christine Hubert, extrait du Bulletin la « question tsigane » est considérée comme de l’Association des Enfants cachés, n° 8, mars 1998) 4 ZONE GOUVERNÉE DEPUIS LE QUARTIER GÉNÉRAL compliquée, dans la mesure où elle englobe des NB. Les autres camps d’internement (ceux destinés ALLEMAND DE BRUXELLES aspects raciaux, sociaux et culturels, les auto- aux Juifs) ne figurent pas sur cette carte. -

Maintenir L'ordre À Lyon 1940-1943

Université Lyon 2 IEP de Lyon Séminaire d’Histoire contemporaine Mémoire de fin d’études Maintenir l’ordre à Lyon 1940-1943 MANZONI Delphine Sous la direction de Bruno Benoît Mémoire soutenu le 04/09/2007 Table des matières Dédicace . 5 Remerciements . 6 Introduction générale . 7 Chapitre préliminaire : De la défaite à l’instauration d’un ordre nouveau : L’état des lieux de la France et de la ville de Lyon en 1940 . 12 I De la drôle de guerre à la débâcle : La France foudroyée20 . 14 A – Une guerre qui se fait attendre… . 14 B – …Mais qui ne s’éternise pas : une défaite à plate couture . 16 II L’instauration d’un ordre nouveau . 18 A- L’Etat français ou la mise en place d’une véritable monarchie pétainiste . 18 B- La révolution nationale : l’ordre nouveau au service du III Reich . 21 Chapitre I : Les protagonistes du maintien de l’ordre . 25 Introduction : Créer une police au service de Vichy : étatisation et épuration de la police . 25 I La mise en place d’un état policier : police nationale et polices spéciales, la distribution des compétences au service de l’ordre nouveau . 26 A- Deux réformes majeures pour une police nationale au service de Vichy . 27 B- Les polices spéciales : police politique de Vichy . 35 II La construction d’un nouvel édifice policier : le préfet régional, pivot du système . 39 A- Le préfet de région : innovation majeur de Vichy dans un objectif de concentration . 39 B- Le préfet de région : sommet de la hiérarchie locale . 43 Conclusion . 48 Chapitre 2 : Le maintien de l’ordre au quotidien . -

Paul Touvier and the Crime Against Humanity'

Paul Touvier and the Crime Against Humanity' MICHAEL E. TIGARt SUSAN C. CASEYtt ISABELLE GIORDANItM SIVAKUMAREN MARDEMOOTOOt Hi SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION ............................................... 286 II. VICHY FRANCE: THE BACKGROUND ................................ 286 III. TOUVIER'S ROLE IN VICHY FRANCE ................................ 288 IV. THE CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY ................................. 291 A The August 1945 Charter ................................... 291 B. The French Penal Code .................................... 293 C. The Barbie Case: Too Clever by Half ........................... 294 V. THE TouviER LITIGATION ....................................... 296 A The Events SurroundingTouvier's Captureand the PretrialLegal Battle ... 296 B. Touvier's Day in Court ..................................... 299 VI. LEGAL ANALYSIS: THE STATE AGENCY DILEMMA.. ...................... 304 VII. CONCLUSION ............................................... 309 " The idea for this essay began at a discussion of the Touvier trial with Professor Tigar's students at the Facut de Droit at Aix-en-Provence, with the assistance of Professor Andr6 Baldous. Ms. Casey provided further impetus for it by her research assistance on international human rights issues, and continued with research and editorial work as the essay developed. Ms. Giordani researched French law and procedure and obtained original sources. Mr. Mardemootoo worked on further research and assisted in formulating the issues. The translations of most French materials were initially done by Professor Tigar and reviewed by Ms. Giordani and Mr. Mardemootoo. As we were working on the project, the Texas InternationalLaw Journaleditors told us of Ms. Finkelstein's article, and we decided to turn our effort into a complementary piece that drew some slightly different conclusions. if Professor of Law and holder of the Joseph D. Jamail Centennial Chair in Law, The University of Texas School of Law. J# J.D. -

Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy

Dr. Francesco Gallo OUTSTANDING FAMILIES of Aiello Calabro (CS) Italy from the XVI to the XX centuries EMIGRATION to USA and Canada from 1880 to 1930 Padua, Italy August 2014 1 Photo on front cover: Graphic drawing of Aiello of the XVII century by Pietro Angius 2014, an readaptation of Giovan Battista Pacichelli's drawing of 1693 (see page 6) Photo on page 1: Oil painting of Aiello Calabro by Rosario Bernardo (1993) Photo on back cover: George Benjamin Luks, In the Steerage, 1900 Oil on canvas 77.8 x 48.9 cm North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. Purchased with funds from the Elizabeth Gibson Taylor and Walter Frank Taylor Fund and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.12 2 With deep felt gratitude and humility I dedicate this publication to Prof. Rocco Liberti a pioneer in studying Aiello's local history and author of the books: "Ajello Calabro: note storiche " published in 1969 and "Storia dello Stato di Aiello in Calabria " published in 1978 The author is Francesco Gallo, a Medical Doctor, a Psychiatrist, a Professor at the University of Maryland (European Division) and a local history researcher. He is a member of various historical societies: Historical Association of Calabria, Academy of Cosenza and Historic Salida Inc. 3 Coat of arms of some Aiellese noble families (from the book by Cesare Orlandi (1734-1779): "Delle città d'Italia e sue isole adjacenti compendiose notizie", Printer "Augusta" in Perugia, 1770) 4 SUMMARY of the book Introduction 7 Presentation 9 Brief History of the town of Aiello Calabro -

DP Musée De La Libération UK.Indd

PRESS KIT LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 OPENING 25 AUGUST 2019 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN The musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin will be ofcially opened on 25 August 2019, marking the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of Paris. Entirely restored and newly laid out, the museum in the 14th arrondissement comprises the 18th-century Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau and the adjacent 19th-century building. The aim is let the general public share three historic aspects of the Second World War: the heroic gures of Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque and Jean Moulin, and the liberation of the French capital. 2 Place Denfert-Rochereau, musée de la Libération de Paris – musée-Général Leclerc – musée Jean Moulin © Pierre Antoine CONTENTS INTRODUCTION page 04 EDITORIALS page 05 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES page 06 THE MUSEUM OF TOMORROW: THE CHALLENGES A NEW HISTORICAL PRESENTATION page 07 AN EXHIBITION IN STEPS page 08 JEAN MOULIN (¡¢¢¢£¤) page 11 PHILIPPE DE HAUTECLOCQUE (¢§¢£¨) page 12 SCENOGRAPHY: THE CHOICES page 13 ENHANCED COLLECTIONS page 15 3 DONATIONS page 16 A MUSEUM FOR ALL page 17 A HERITAGE SETTING FOR A NEW MUSEUM page 19 THE INFORMATION CENTRE page 22 THE EXPERT ADVISORY COMMITTEE page 23 PARTNER BODIES page 24 SCHEDULE AND FINANCING OF THE WORKS page 26 SPONSORS page 27 PROJECT PERSONNEL page 28 THE CITY OF PARIS MUSEUM NETWORK page 29 PRESS VISUALS page 30 LE MUSÉE DE LA LIBÉRATION DE PARIS MUSÉE DU GÉNÉRAL LECLERC MUSÉE JEAN MOULIN INTRODUCTION New presentation, new venue: the museums devoted to general Leclerc, the Liberation of Paris and Resistance leader Jean Moulin are leaving the Gare Montparnasse for the Ledoux pavilions on Place Denfert-Rochereau. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé Annika Barrett Whitworth University

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University History of Christianity II: TH 314 Honors Program 5-2017 Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé Annika Barrett Whitworth University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/th314h Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Annika , "Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé" Whitworth University (2017). History of Christianity II: TH 314. Paper 16. https://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/th314h/16 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Christianity II: TH 314 by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. Annika Barrett The Story of Brother Roger and the Formation of Taizé What is it about the monastic community in Taizé, France that has inspired international admira- tion, especially among young people? Don’t most people today think of monasteries as archaic and dull, a place for religious extremists who were una- ble to marry? Yet, since its birth in the mid 1900s, Brother Roger at a prayer in Taizé. Taizé has drawn hundreds of thousands of young Photo credit: João Pedro Gonçalves adult pilgrims from all around the world, influenced worship practices on an international scale, and welcomed spiritual giants from Protestant, Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox backgrounds. Un- like traditional monastic orders, Taizé is made up of an ecumenical brotherhood that lives in dy- namic adaptability, practicing hospitality for culturally diverse believers while remaining rooted in the gospel. -

A Century at Sea Jul

Guernsey's A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI Friday - July 19, 2019 A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI 1: NS Savannah Set of China (31 pieces) USD 800 - 1,200 A collection of thirty-one (31) pieces of china from the NS Savannah. This set of china includes the following pieces: two (2) 10" round plates, three (3) 9 1/2" round plates, one (1) 10" novelty plate, one (1) 9 1/4" x 7" oval plate, one (1) 7 1/4" round plate, four (4) 6" round plates, one (1) ceramic drinking pitcher, one (1) cappachino cup and saucer (diameter of 4 1/2"), two (2) coffee cups and saucers (diameter 4"), one (1) 3 1/2" round cup, one (1) 3" x 3" round cup, one (1) 2 1/2" x 3" drinking glass, one (1) mini cognac glass, two (2) 2" x 4 1/2" shot glasses, three (3) drinking glasses, one (1) 3" x 5" wine glass, two (2) 4 1/2" x 8 3/4" silver dishes. The ship was remarkable in that it was the first nuclear-powered merchant ship. It was constructed with funding from United States government agencies with the mission to prove that the US was committed to the proposition of using atomic power for peace and part of President Eisenhower's larger "Atoms for Peace" project. The sleek and modern design of the ship led to some maritime historians believing it was the prettiest merchant ship ever built. This china embodies both the mission of using nuclear power for peace while incorporating the design inclinations of the ship. -

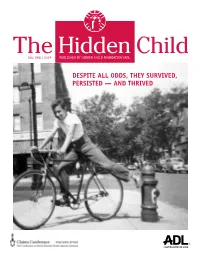

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children. -

Twenty Or So Years Ago, I Had the Great Privilege of Being at a Mass in St Peter’S Rome Celebrated by Pope St John Paul II

Twenty or so years ago, I had the great privilege of being at a mass in St Peter’s Rome celebrated by Pope St John Paul II. Also present on that occasion was the Protestant Brother Roger Schutz, the founder and then prior of the ecumenical monastic community of Taizé. Both now well on in years and ailing in different ways, Pope John Paul and Brother Roger had a well known friendship and it was touching to see the Pope personally give communion to his Protestant friend. This year, the Common Worship feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary, known by most Christians as her Assumption, the Dormition or the Falling Asleep, is also the eve of the fifteenth anniversary of Roger’s horrific, and equally public, murder in his own monastic church, within six months of the death of John Paul himself. I want to suggest three themes that were characteristic both of Mary and Brother Roger and also offer us a sure pathway for our own discipleship: joy, simplicity and mercy. I was led to these by an interview on TV many years ago with Br Alois, Brother Roger’s successor as prior of Taizé, who described how they were at the heart of Brother Roger’s approach to life and guidance of his community. He had written them into the Rule of Taizé, and saw them as a kind of summary of the Beatitudes: [3] "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. [4] "Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. -

(IN)CONNUE by Jennifer Ann Young

ABSTRACT DEUIL D’UNE (IN)CONNUE By Jennifer Ann Young Contemporary French author Patrick Modiano’s novels center almost entirely around memory and the traumatic events surrounding the Occupation. Modiano has spent most of his life dealing with the guilty remorse of having been born directly following the Occupation, while hundreds of thousands of others, including his estranged father, experienced it directly. Modiano’s Dora Bruder focuses on the chance encounter with a stranger and the possibility of caring deeply for this person. The heroine, Dora Bruder, mesmerizes Modiano as he devotes six years of his life to finding out the fate of this young girl, who disappeared during the Occupation. Her fate becomes his mission. This thesis explores the possibilities of loving someone without ever having met him or her. It also further discovers the (im)possibility of mourning the loss of an unknown individual. DEUIL D’UNE (IN)CONNUE A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of French by Jennifer Ann Young Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor __________________________________ James Creech Reader __________________________________ Elisabeth Hodges Reader __________________________________ Sven-Erik Rose TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………............. 1 Transformed Identities: La Place de l’Etoile and Dora Bruder…………….… 3 Lieux, Photos et Flâneur/Flâneuse…………………………………………... 8 Le Vide……………………………………………………………………… 19 Ecriture: Mourning and Melancholia……………………………………….… 23 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………… 32 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………. 33 ii Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the help of several individuals. The long, but rewarding road to its completion is due in part to your support, encouragement, and advice. -

Klaus Barbie Pre-Trial Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt509nf111 No online items Inventory of the Klaus Barbie pre-trial records Finding aid prepared by Josh Giglio. Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6010 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2008, 2014 Inventory of the Klaus Barbie 95008 1 pre-trial records Title: Klaus Barbie pre-trial records Date (inclusive): 1943-1985 Collection Number: 95008 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of the Materials : In French and German. Physical Description: 8 manuscript boxes(3.2 linear feet) Abstract: Trial instruction, including depositions and exhibits, in the case of Klaus Barbie before the Tribunal de grande instance de Lyon, relating to German war crimes in France during World War II. Photocopy. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Barbie, Klaus, 1913- , defendant. Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. We will then advise you of the accessibility of the material you wish to see or hear. Please note that not all audiovisual material is immediately accessible. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1995. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu/ .