Volume 21 1994 Issue 59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

Vegetable Trade Between Self-Governance and Ethnic Entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gebresenbet, Fana Working Paper Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1 Provided in Cooperation with: Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen Suggested Citation: Gebresenbet, Fana (2018) : Perishable state-making: Vegetable trade between self-governance and ethnic entitlement in Jigjiga, Ethiopia, DIIS Working Paper, No. 2018:1, ISBN 978-87-7605-911-8, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS), Copenhagen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/179454 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under -

Country of Origin Information Report Somalia July 2008

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SOMALIA 30 JULY 2008 UK BORDER AGENCY COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 30 JULY 2008 SOMALIA Contents Preface LATEST NEWS EVENTS IN SOMALIA, FROM 4 JULY 2008 TO 30 JULY 2008 REPORTS ON SOMALIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED SINCE 4 JULY 2008 Paragraphs Background Information GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................. 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.04 ECONOMY ................................................................................................. 2.01 Currency change, 2008 ................................................................ 2.06 Drought and famine, 2008 ........................................................... 2.10 Telecommunications.................................................................... 2.14 HISTORY ................................................................................................... 3.01 Collapse of central government and civil war ........................... 3.01 Peace initiatives 2000-2006 ......................................................... 3.14 ‘South West State of Somalia’ (Bay and Bakool) ...................... 3.19 ‘Puntland’ Regional Administration............................................ 3.20 The ‘Republic of Somaliland’ ...................................................... 3.21 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................... 4.01 CONSTITUTION ......................................................................................... -

Horn of Africa Crisis Situation Report No

Horn of Africa Crisis Situation Report No. 28 23 December 2011 This report is produced by OCHA Eastern Africa in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by OCHA in New York. It covers the period from 16 to 23 December. The next report will be issued on 30 December. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • Tensions remain high in North Eastern Province of Kenya following a series of explosive attacks targeting military and police convoys in the area. • Aid workers have further reduced operations in the Dadaab refugee camps following heightened insecurity. • WHO has called on health partners to intensify cholera preventative activities in Mogadishu following an increase in cases. II. Situation Overview While drought conditions have eased in many locations due to the recent rains, drought conditions are expected to worsen in parts of the Horn of Africa in the coming months as the dry season sets in. A new food security analysis of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system in Djibouti has indicated that the food security situation in Obock Region has deteriorated from ‘Stressed’ (IPC Phase 2) to ‘Crisis’ (IPC Phase 3).Deterioration in food security conditions is now likely in coastal and southeast areas as well. In Ethiopia, even as the seasonal deyr (October-December) rains continue in most lowland areas of southern and south-eastern Ethiopia, drought conditions are expected to worsen in the northernmost parts of the Afar Region and parts of northern Somali Region in the coming month. On the other hand, drought conditions in the northern, north-eastern and southern parts of Kenya have significantly eased following good rainfall received in the October-December short rains season.In Somalia, while the deyr rains have subsided in many parts of Lower and Middle Juba regions, flooding continues to affect many settlements in Middle Juba. -

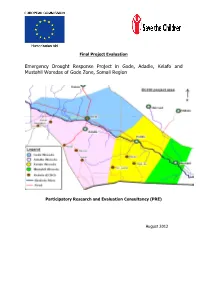

Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region

Final Project Evaluation Emergency Drought Response Project in Gode, Adadle, Kelafo and Mustahil Woredas of Gode Zone, Somali Region Participatory Research and Evaluation Consultancy (PRE) August 2012 Content SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................IV 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT INTERVENTION AREA ......................................................... 1 1.2 BACKGROUND TO SC UK’ S EMERGENCY DROUGHT RESPONSE ........................................ 2 2. THE FINAL EVALUATION ........................................................................................ 4 2.1 SCOPE OF THE EVALUATION .................................................................................. 4 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 Overall approach......................................................................................... 4 2.2.2 Desk review................................................................................................ 5 2.2.3 Field assessment......................................................................................... 5 2.2.4 Data collection and analysis ......................................................................... 9 3. EVALUATION FINDINGS ........................................................................................ -

The Role of Education in Livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia

J U N E 2 0 1 1 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice A report for the BRIDGES Project The Role of Education in Livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia Elanor Jackson ©2011 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Acknowledgements This study was funded by the Department for International Development as part of the BRIDGES pilot project, implemented by Save the Children UK, Mercy Corps, and Islamic Relief in the Somali Region. The author especially appreciates the support and ideas of Alison Napier of Tufts University in Addis Ababa. Thanks also to Mercy Corps BRIDGES project staff in Jijiga and Gode, Islamic Relief staff and driver in Hargelle, Save the Children UK staff in Dire Dawa, and the Tufts driver. In particular, thanks to Hussein from Mercy Corps in Jijiga for organizing so many of the interviews. Thanks also to Andy Catley from Tufts University and to Save the Children UK, Islamic Relief, Mercy Corps, and Tufts University staff in Addis Ababa for their ideas and logistical assistance. -

Groundwater Exploration and Assessment in the Eastern Lowlands and Associated Highlands of the Ogaden Basin Area, Eastern Ethiopia: Phase 1 Final Technical Report

Prepared in cooperation with the United States Geological Survey Groundwater Exploration and Assessment in the Eastern Lowlands and Associated Highlands of the Ogaden Basin Area, Eastern Ethiopia: Phase 1 Final Technical Report By Saud Amer, Alain Gachet, Wayne R. Belcher, James R. Bartolino, and Candice B. Hopkins Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Purpose and scope ............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Study Area ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Geographic location ............................................................................................................................................ 6 2.2. Climate ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 3. Geology .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Diaspora Et Terrorisme

Marc-An toi ne Pérous de M ntclos r Diaspora et terrorisme PRE SS ES DE SC IENC ES PO Diaspora et terrorisme Du même auteur Le Nigeria, Paris, Karthala, coll. « Méridiens », 1994, 323 p. Violence et sécurité urbaines en Afrique du Sud et au Nigeria, un essai de privatisation: Durban,johannesburg, Kano, Lagoset Port-Harcourt, Paris, L'Harmattan, coll. « Logiques politiques », 1997, 2 vol., 303 p. et 479 p. L'aide humanitaire, aide à la guerre?, Bruxelles, Complexe, 2001, 208 p. Villes et violences en Afrique subsabarienne, Paris, Karthala-IRD, 2002, 311 p. Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos Diaspora et terrorisme PRESSES DE SCIENCES PO Caralogage Électre-Bibliographie (avec le concours des Services de documentation de la FNSP) Pérouse de Monrclos, Marc-Antoine Diaspora er terrorisme. - Paris: Pressesde SciencesPo, 2003. - (Collection académique) ISBN 2-7246-0897-6 RAMEAU: réfugiés somaliens envois de fonds: Somalie Somalie: politique er gouvernement: 1960-... DEWEY: 325 : Migrations internationales et colonisation 320.7 : Sciencepolitique (politique er gouvernemenr). Conjoncture et condirions politiques 670 : Somalie Public concerné: Public motivé La loi de 1957 sur la propriété intellectuelle interdit expressément la photocopie à usage collectif sans autorisation des ayants droit (seule la phorocopie à usage privé du copiste est aurorisée). Nous rappelons donc que toute reproduction, partielle ou totale, du présent ouvrage esr interdite sans autorisarion de I'édireur ou du Centre français d'exploirarion du droit de copie (CFC, 3, rue Hautefeuille, 75006 Paris). Cauoertur«: Emmanuel Le Ngoc © 2003. PRESSESDE LA FONDATION NATIONALE DES SCIENCES POLITIQUES Table des matières AVANT-PROPOS Il INTRODUCTION 13 CHAPITRE 1. Somalie année zéro: les raisons d'une destruc- tion 21 La théorie du complot 22 L'explication par la tradition plutôt que par l'histoire 27 La dictature au centre des accusations 39 Sur les décombres de l'État 42 CHAPITRE 2. -

Somaliland: the Strains of Success

Somaliland: The Strains of Success Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°113 Nairobi/Brussels, 5 October 2015 I. Overview Somaliland’s hybrid system of tri-party democracy and traditional clan-based gov- ernance has enabled the consolidation of state-like authority, social and economic recovery and, above all, relative peace and security but now needs reform. Success has brought greater resources, including a special funding status with donors – especially the UK, Denmark and the European Union (EU) – as well as investment from and diplomatic ties with Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), though not inter- national recognition. It is increasingly part of the regional system; ties are especially strong with Ethiopia and Djibouti. Given the continued fragility of the Somalia Federal Government (SFG), which still rejects its former northern region’s independence claims, and civil war across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, Somaliland’s continued stabil- ity is vital. This in turn requires political reforms aimed at greater inclusion, respect for mediating institutions (especially the professional judiciary and parliament) and a regional and wider internationally backed framework for external cooperation and engagement. Successful state building has, nevertheless, raised the stakes of holding – and los- ing – power. While Somaliland has remained largely committed to democratic gov- ernment, elections are increasingly fraught. Fear of a return to bitter internal conflict is pushing more conservative politics: repression of the media and opposition, as well as resistance to reforming the increasingly unsustainable status quo. Recurrent po- litical crises and delayed elections (now set for March 2017) risk postponing much needed internal debate. The political elites have a limited window to decide on steps necessary to rebuild the decaying consensus, reduce social tensions and set an agenda for political and institutional reform. -

Diasporas, Development and Peacemaking in the Horn of Africa Edited by Liisa Laakso and Petri Hautaniemi

This PDF is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Licence. Further details regarding permitted usage can be found at http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Print and ebook editions of this work are available to purchase from Zed Books (www.zedbooks.co.uk). A frica Now Africa Now is published by Zed Books in association with the inter nationally respected Nordic Africa Institute. Featuring highquality, cuttingedge research from leading academics, the series addresses the big issues confronting Africa today. Accessible but indepth, and wideranging in its scope, Africa Now engages with the critical political, economic, sociological and development debates affecting the continent, shedding new light on pressing concerns. Nordic Africa Institute The Nordic Africa Institute (Nordiska Afrikainstitutet) is a centre for research, documentation and information on modern Africa. Based in Uppsala, Sweden, the Institute is dedicated to providing timely, critical and alternative research and analysis of Africa and to cooperation with African researchers. As a hub and a meeting place for a growing field of research and analysis, the Institute strives to put knowledge of African issues within reach of scholars, policy makers, politicians, media, students and the general public. The Institute is financed jointly by the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden). www.nai.uu.se Forthcoming titles Margaret C. Lee (ed.), Africa’s World Trade Godwin Murunga, Duncan Okello and Anders Sjögren (eds), Kenya: The Struggle for a New Constitutional Order Thiven Reddy, South Africa: Beyond Apartheid and Liberal Democracy Lisa Åkesson and Maria Eriksson Baaz (eds), Africa’s Return Migrants Titles already published Fantu Cheru and Cyril Obi (eds), The Rise of China and India in Africa Ilda Lindell (ed.), Africa’s Informal Workers Iman Hashim and Dorte Thorsen, Child Migration in Africa Prosper B. -

State-Making in Somalia and Somaliland

The London School of Economics and Political Science STATE -MAKING IN SOMALIA AND SOMALILAND Understanding War, Nationalism and State Trajectories as Processes of Institutional and Socio-Cognitive Standardization Mogadishu ● Dominik Balthasar A thesis submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics (LSE) for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2012 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 105,510. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Sue Redgrave. Cover illustration: Map source, URL: http://tinyurl.com/97ao5ug, accessed, 15 September 2012, adapted by the author. 2 Abstract Although the conundrums of why states falter, how they are reconstituted, and under what conditions war may be constitutive of state-making have received much scholarly attention, they are still hotly debated by academics and policy analysts. Advancing a novel conceptual framework and analysing diverse Somali state trajectories between 1960 and 2010, this thesis adds to those debates both theoretically and empirically.