Thanatography in Stephen King's Short Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set in Maine

Books Set in Maine Books Set in Maine Author Title Location Andrews, William D. Mapping Murder Atwood, Margaret The Handmaid's Tale Bachman, Richard Blaze Barr, Nevada Boar Island Acadia National Park One Goal: a Coach, a Team, and the Game That Brought a Divided Town Bass, Amy Together Lewiston Blake, Sarah The Guest Book an island in Maine Blake, Sarah Grange House A resort in Maine 2/26/2021 1 Books Set in Maine We Were an Island: the Maine life of Art Blanchard III, Peter P and Ann Kellam Placentia Island Bowen, Brenda Enchanted August an island in Maine Boyle, Gerry Lifeline Burroughs, Franklin Confluence: Merrymeeting Bay Merrymeeting Bay Chase, Mary Ellen The Lovely Ambition Downeast Maine Chee, Alexander Edinburgh Chute, Carolyn The Beans of Egypt Maine Coffin, Bruce Robert Within Plain Sight Portland 2/26/2021 2 Books Set in Maine Coffin, Bruce Robert Among the Shadows Portland Creature Discomforts: a dog lover's Conant, Susan mystery Acadia National Park Connolly, John Bad Men Maine island Connolly, John The Woman in the Woods Coperthwaite, William S. A Handmaid Life Portland Cronin, Justin The Summer Guest a fishing camp in Maine The Bar Harbor Retirement Home For DeFino, Terri-Lynne Famous Writers Bar Harbor Dickson, Margaret Octavia's Hill 2/26/2021 3 Books Set in Maine Doiron, Paul Almost Midnight wilderness areas Doiron, Paul The Poacher's Son wilderness areas Ferencik, Erika The River at Night wilderness areas The Stranger in the Woods: the extraordinary story of the last true Finkel, Michael hermit Gerritsen, Tess Bloodstream Gilbert, Elizabeth Stern Men Maine islands Gould, John Maine's Golden Road Grant, Richard Tex and Molly in the Afterlife\ 2/26/2021 4 Books Set in Maine Graves, Sarah The Dead Cat Bounce (Home Repair is HomicideEastport #1) Gray, T.M. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

Hitchhiking: the Travelling Female Body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Hitchhiking: the travelling female body Vivienne Plumb University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Plumb, Vivienne, Hitchhiking: the travelling female body, Doctorate of Creative Arts thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3913 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Hitchhiking: the travelling female body A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctorate of Creative Arts from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Vivienne Plumb M.A. B.A. (Victoria University, N.Z.) School of Creative Arts, Faculty of Law, Humanities & the Arts. 2012 i CERTIFICATION I, Vivienne Plumb, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Creative Arts, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Vivienne Plumb November 30th, 2012. ii Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the support of my friends and family throughout the period of time that I have worked on my thesis; and to acknowledge Professor Robyn Longhurst and her work on space and place, and I would also like to express sincerest thanks to my academic supervisor, Dr Shady Cosgrove, Sub Dean in the Creative Arts Faculty. Finally, I would like to thank the staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, in particular Olena Cullen, Teaching and Learning Manager, Creative Arts Faculty, who has always had time to help with any problems. -

Death Valley Junior Ranger Book

How to be a Junior Ranger Complete the number of activities for the animal level i. you would like to achieve. Circle that animal below. Roadrunner Level: Chuckwalla Level: Bighorn Sheep Level: at least 4 activities at least 6 activities at least 9 activities Compare Death Valley to where you live. You can watch the park movie at the Furnace Creek Visitor Center for inspiration. How is Death Valley similar How is Death Valley different to your home? from your home? ~o Become an Official Junior Ranger! Go to a visitor center or ranger station in Death Valley National Park. Show a ranger this book, and tell them about your adventure. You will be sworn in as an official Junior Ranger and get a badge! Junior Ranger patches Books may also be are available for purchase mailed to: at the bookstore. Just show Death Valley National Park Junior Ranger Program the certificate on the PO Box 579 back of this book! Death Valley, CA 92328 Let's get started! Packing for Your Adventure Before we go out on our Junior Ranger adventure, we must make sure we are prepared! If we bring the right things, we can have a fun and safe adventure in Death Valley! First things first-bring plenty of water, and remind your family to drink it! Help me pack for my hike by circling what I should bring! How might summer visitors prepare differently than visitors in the winter? Map of Your Adventure This is a map of your adventure in Death Valley. Draw the path you traveled to explore the hottest, driest, and lowest national park in the United States! Circle the places that you visited, and fill in the names of the blank spaces on the map. -

Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 606 CS 216 137 AUTHOR Power, Brenda Miller, Ed.; Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., Ed.; Chandler, Kelly, Ed. TITLE Reading Stephen King: Issues of Censorship, Student Choice, and Popular Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3905-1 PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 246p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 39051-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Censorship; Critical Thinking; *Fiction; Literature Appreciation; *Popular Culture; Public Schools; Reader Response; *Reading Material Selection; Reading Programs; Recreational Reading; Secondary Education; *Student Participation IDENTIFIERS *Contemporary Literature; Horror Fiction; *King (Stephen); Literary Canon; Response to Literature; Trade Books ABSTRACT This collection of essays grew out of the "Reading Stephen King Conference" held at the University of Mainin 1996. Stephen King's books have become a lightning rod for the tensions around issues of including "mass market" popular literature in middle and 1.i.gh school English classes and of who chooses what students read. King's fi'tion is among the most popular of "pop" literature, and among the most controversial. These essays spotlight the ways in which King's work intersects with the themes of the literary canon and its construction and maintenance, censorship in public schools, and the need for adolescent readers to be able to choose books in school reading programs. The essays and their authors are: (1) "Reading Stephen King: An Ethnography of an Event" (Brenda Miller Power); (2) "I Want to Be Typhoid Stevie" (Stephen King); (3) "King and Controversy in Classrooms: A Conversation between Teachers and Students" (Kelly Chandler and others); (4) "Of Cornflakes, Hot Dogs, Cabbages, and King" (Jeffrey D. -

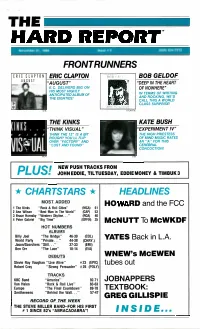

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

The Shawl by Cynthia Ozick

The Shawl by Cynthia Ozick 1 Table of Contents The Shawl “Just as you can’t About the Book.................................................... 3 grasp anything About the Author ................................................. 5 Historical and Literary Context .............................. 7 without an Other Works/Adaptations ..................................... 9 opposable thumb, Discussion Questions.......................................... 10 you can’t write Additional Resources .......................................... 11 Credits .............................................................. 12 anything without the aid of metaphor. Metaphor is the mind’s opposable thumb.” Preface What is the NEA Big Read? No event in modern history has inspired so many books as A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big the Holocaust. This monumental atrocity has compelled Read broadens our understanding of our world, our thousands of writers to reexamine their notions of history, communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a humanity, morality, and even theology. None of these good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers books, however, is quite like Cynthia Ozick's The Shawl—a grants to support innovative community reading programs remarkable feat of fiction which starts in darkest despair and designed around a single book. brings us, without simplification or condescension, to a glimmer of redemption. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. -

Death, Transition, and Resilience: a Narrative Study of the Academic Persistence of Bereaved College Students

DEATH, TRANSITION, AND RESILIENCE: A NARRATIVE STUDY OF THE ACADEMIC PERSISTENCE OF BEREAVED COLLEGE STUDENTS Cari Ann Urabe A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2020 Committee: Maureen E. Wilson, Committee Co-Chair D-L Stewart, Committee Co-Chair Paul Cesarini Graduate Faculty Representative Christina J. Lunceford © 2020 Cari Ann Urabe All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maureen E. Wilson, Committee Co-Chair D-L Stewart, Committee Co-Chair This study used narrative inquiry to focus on the lived experiences of undergraduate and graduate students who have experienced a significant death loss during their studies and have academically persisted in the face of adversity. The purpose of this research was to understand and describe how undergraduate and graduate students academically persist within higher education after a significant death loss. Providing this affirmative narrative illuminated the educational resilience that occurs following a death loss experience. Using educational resilience as the conceptual model and Schlossberg’s transition theory as the theoretical framework, the overarching research question that guided this study was: What are the narratives of bereaved college students who academically persist in the face of adversity? Participants included seven undergraduate and graduate students from three institutions of higher education across the United States. Participants engaged in two semi-structured interviews and an electronic journaling activity to share their death loss experience. Interviews were conducted face-to-face and virtually. Composite narratives were used to present the data from this study. The seven participants in this study were highlighted through four composite characters who met monthly at a Death Café. -

Reading Group Guide

FONT: Anavio regular (wwwUNDER.my nts.com) THE DOME ABOUT THE BOOK IN BRIEF: The idea for this story had its genesis in an unpublished novel titled The Cannibals which was about a group of inhabitants who find themselves trapped in their apartment building. In Under the Dome the story begins on a bright autumn morning, when a small Maine town is suddenly cut off from the rest of the world, and the inhabitants have to fight to survive. As food, electricity and water run short King performs an expert observation of human psychology, exploring how over a hundred characters deal with this terrifying scenario, bringing every one of his creations to three-dimensional life. Stephen King’s longest novel in many years, Under the Dome is a return to the large-scale storytelling of his ever-popular classic The Stand. IN DETAIL: Fast-paced, yet packed full of fascinating detail, the novel begins with a long list of characters, including three ‘dogs of note’ who were in Chester’s Mill on what comes to be known as ‘Dome Day’ — the day when the small Maine town finds itself forcibly isolated from the rest of America by an invisible force field. A woodchuck is chopped right in half; a gardener’s hand is severed at the wrist; a plane explodes with sheets of flame spreading to the ground. No one can get in and no one can get out. One of King’s great talents is his ability to alternate between large set-pieces and intimate moments of human drama, and King gets this balance exactly right in Under the Dome. -

A Collection of Short Stories

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1993 No place called home| A collection of short stories Mia Laurence The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Laurence, Mia, "No place called home| A collection of short stories" (1993). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3091. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3091 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFTFT T) T TRRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of No Place Called Home: a collection of short stories by Mia Laurence Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts University of Montana 1993 Approved by Chair, BoStrd of^E^miners } L/f Dean, Graduate School a. flii UMI Number: EP33868 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

JUST AFTER SUNSET Ebook Free Download

JUST AFTER SUNSET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen King | 539 pages | 04 Mar 2010 | Simon + Schuster Inc. | 9781439144916 | English | none JUST AFTER SUNSET PDF Book Terrible, in poor taste, I'm disgusted. Then they were both gone. He came upon a Budweiser can and kicked it awhile. Harvey's Dream-short but chilling.. Maybe her first name was Sally, but David thought he would have remembered a name like that; there were so few Sallys these days. Baby wants to dance. His shadow grew long, shortened in the glow of the hanging fluorescents, then grew long again. What we have here seems to be more like a collection of literary doodles or proof of concepts that just kind of fell out of King's brain. United States of America. And where, exactly, would she have gone looking for fun? N: A psychiatrist commits suicide and his sister reads the file on his last patient, an OCD man named N. The horror has the old school feel to it and is quite effective in places but not as a whole. It was a barn of a place—there had to be five hundred people whooping it up—but he had no concerns about finding Willa. Get A Copy. He dropped his eyes to his feet instead. I said yes immediately. It dealt a little with identity but was mostly a writer gathering up the courage to do something about a bad situation. Read those two lines at the bottom and then we can get this show on the road. It was red, white, and blue; in Wyoming, they did seem to love their red, white, and blue.