10485.Ch01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagon Master Caravana De Paz 1950, USA

Wagon Master Caravana de paz 1950, USA Prólogo: Una familia de bandoleros, los Cleggs, atraca un banco asesinando D: John Ford; G: Frank S. Nugent, a sangre fría a uno de sus empleados. Patrick Ford, John Ford; Pr: Lowell J. Farrell, Argosy Pictures; F: Bert Títulos de crédito: imágenes de una caravana de carretas atravesando un Glennon; M: Richard Hageman; río, rodando a través de (como dice la canción que las acompaña) “ríos y lla- Mn: Jack Murray, Barbara Ford; nuras, arenas y lluvia”. A: Ben Johnson, Joanne Dru, Harry Carey Jr., Ward Bond, 1849. A la pequeña población de Cristal City llegan dos tratantes de caballos, Charles Kemper, Alan Mowbray, Travis (Ben Johnson) y Sandy (Harry Carey Jr.) con la finalidad de vender sus Jane Darwell, Ruth Clifford, Russell recuas. Son abordados por un grupo de mormones que desean comprarles los Simpson, Kathleen O’Malley, caballos y contratarles como guías para que conduzcan a su gente hasta el río James Arness, Francis Ford; San Juan, más allá del territorio navajo, hasta “el valle que el señor nos tiene B/N, 86 min. DCP, VOSE reservado, que ha reservado a su pueblo para que lo sembremos y lo cultive- mos y lo hagamos fructífero a sus ojos”. Los jóvenes aceptan la primera oferta pero rechazan la segunda. A la mañana siguiente la caravana mormona se pone en camino, vigilada muy de cerca por las intolerantes gentes del pueblo. Travis y Sandy observan la partida sentados en una cerca. De repente, en apenas dos versos de la can- ción que entona Sandy, el destino da un vuelco y los jóvenes deciden incorpo- rarse al viaje hacia el oeste: “Nos vemos en el río. -

English 488/588 – 36001/36002 NATIVE AMERICAN FILM Professor Kirby Brown Class Meetings Office: 523 PLC Hall TR: 2-3:50Pm Offi

English 488/588 – 36001/36002 NATIVE AMERICAN FILM Professor Kirby Brown Class Meetings Office: 523 PLC Hall TR: 2-3:50pm Office Hours: T, 4-5pm; W, 9-11am, and by email appt. Location: ED 276 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION There is perhaps no image more widely recognized yet more grossly misunderstood in American popular culture than the “Indian.” Represented as everything from irredeemable savages and impediments to progress to idealized possessors of primitive innocence and arbiters of new-age spiritualism, “the Indian” stands as an anachronistic relic of a bygone era whose sacrifice on the altars of modernity and progress, while perhaps tragic, is both inevitable and necessary to the maintenance of narratives of US exceptionalism in the Americas. Though such images have a long history in a variety of discursive forms, the emergence of cinematic technologies in the early twentieth century and the explosion of film production and distribution in the ensuing decades solidified the Noble Savage/Vanishing American as indelible, if contradictory, threads in the fabric of the US national story. Of course, the Reel Indians produced by Hollywood say very little about Real Native peoples who not only refuse to vanish but who consistently reject their prescribed roles in the US national imaginary, insisting instead on rights to rhetorical and representational sovereignty. Through a juxtaposition of critical and cinematic texts, the first third of the course will explore the construction of “Reel Indians” from early ethnographic documentaries and Hollywood Westerns to their recuperation as countercultural anti-heroes in the 60s, 70s and 80s. The last two-thirds of the course will examine the various ways in which Native-produced films of the late 1990s to the present contest— if not outright refuse!—narrative, generic, and representational constructions of “the white man’s Indian” on the way to imagining more complex possibilities for “Real Indians” in the twenty-first century. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Film from Both Sides of the Pacific Arw

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2012 Apr 26th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific arW Avery Fischer Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Fischer, Avery, "Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific arW " (2012). Young Historians Conference. 9. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2012/oralpres/9 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific War Avery Fischer Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 202: History of the United States Portland State University March 21, 2012 Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific War On December 7, 1941, American eyes were focused on a new enemy. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, no longer were Americans concerned only with the European front, but suddenly an attack on American soil lead to a quick chain reaction. By the next day, a declaration of war was requested by President Roosevelt for "a date that will live on in infamy- the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan .. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

215269798.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

John Ford Film Series at Museum of Modern Art

I THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART No. 50 n WEST 53 STREET. NEW YORK 19. N. Y. For Immediate Release ffUFHONl: CIRCLI B-8900 JOHN FORD FILM SERIES AT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART JOHN FORD: NINE FILMS, a new auditorium series at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, will begin with THE IRON HCRSE, June 7-13, daily showings at 3 pm. The 1921* silent film, an epic of the first American trans-continental railroad, features George O'Brien and Madge Bellamy, With the program changing each Sunday, the review of films by Mr, Ford, the eminent American director, will continue daily at 3 and 5:30: June lk-20, FOUR SONS (19ft), with Margaret Mann, Francis X. Bushman, Jr; June 21-27, THE INFORMER (1935), with Victor McLaglen; June 28-July h, STAGECOACH (1929), with John Wayne, Claire Trevor, John Carradine; July 5-11, YOUNG MR. LINCOLN (1939), with Henry Fonda, Alice Brady; July 12-18, LONG VOYAGE HOME (19^0), with John Wayne, Thomas Mitchell, Barry Fitzgerald; July 19-25, T"E GRAPES OF WRATH (19lO), with Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, John Carradine; July 26-Aufust 1, MY DARLING CLEMINTINE (19^6), with Henry Fonda, Linda Darnell, Victor Mature; August 2-8, THE QUIET MAN (1952), with John Wayne, Maureen OfHara, Barry Fitzgerald. THE QUIET MAN will be shown at 3 pm only, Richard Griffith, Curator of the Film Library, says of the new Museum series: "To choose nine films by John Ford for this exhibition will seem to the great director's admirers an act of impertinence. -

Copyright by Joseph Paul Moser 2008

Copyright by Joseph Paul Moser 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Joseph Paul Moser certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Patriarchs, Pugilists, and Peacemakers: Interrogating Masculinity in Irish Film Committee: ____________________________ Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, Co-Supervisor ____________________________ Neville Hoad, Co-Supervisor ____________________________ Alan W. Friedman ____________________________ James N. Loehlin ____________________________ Charles Ramírez Berg Patriarchs, Pugilists, and Peacemakers: Interrogating Masculinity in Irish Film by Joseph Paul Moser, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 For my wife, Jennifer, who has given me love, support, and the freedom to be myself Acknowledgments I owe many people a huge debt for helping me complete this dissertation. Neville Hoad gave me a crash course in critical theory on gender; James Loehlin offered great feedback on the overall structure of the study; and Alan Friedman’s meticulous editing improved my writing immeasurably. I am lucky to have had the opportunity to study with Charles Ramírez Berg, who is as great a teacher and person as he is a scholar. He played a crucial role in shaping the chapters on John Ford and my overall understanding of film narrative, representation, and genre. By the same token, I am fortunate to have worked with Elizabeth Cullingford, who has been a great mentor. Her humility, wit, and generosity, as well as her brilliance and tenacity, have been a continual source of inspiration. -

Lilms Perisllecl

Film History, Volume 9, pp. 5-22, 1997. Text copyrig ht © 1997 David Pierce. Design, etc. copyright© John libbey & Company. ISSN: 0892-2 160. Pri nted in Australia l'lle legion of file conclemnecl - wlly American silenf lilms perisllecl David Pierce f the approximately 1 0 ,000 feature print survives for most silent films, usually therewere films and countless short subjects re not many copies lo begin with . While newspapers leased in the United States before or magazines were printed and sold by the thou O 1928, only a small portion survive . sands, relatively few projection prints were re While so me classics existand are widelyavailable, quired for even the most popular silent films . In the many silent films survive only in reviews, stills, pos earliest days of the industry, producers sold prints, ters and the memories of the few remaining audi and measured success bythe number ofcopies sol d. ence members who saw them on their original By the feature period, beginning around 1914, release. 1 copies were leased lo subdistributors or rented lo Why did most silent films not survive the pas exhibitors, and the owners retained tight control. sage of time? The curren! widespread availability The distribution of silent features was based on a of many tilles on home video, and the popularity of staggered release system, with filmgoers paying silent film presentations with live orchestral accom more lo see a film early in its run. Films opened in paniment might give the impression that silent films downtown theatres, moved lo neighbourhood had always been held in such high regard . -

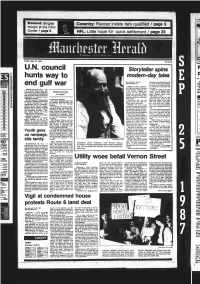

U.N. Council Hunts Way to End Gulf

W eekend: Singles Coventry: Planner insists he’s qualified / page 3 mingle at the Civic T Center / page 9 NFL: Little hope for quick settiement / page 23 aurlipstrr HrraiJi ManchRStRr - A City n! VillnijR Chdrm Friday,I iiw a j, Sept. 25, 1987IWOf 30 Cents S U.N. council Storyteller spins hunts way to modern-day tales B y IS E X1SIR: ‘ By Andrew J. Davis Clements is doing his best to try Herald Reporter to teach children such modern- end gulf war day morals. He said his stories jROPEI Children at Bowers Elemen are non-violent, non-sexist and tary School sat intently listening non-racist. UNITED NATIONS (AP) - The td a story about a blg-cjty ant. "These are children learning N»k 1 U.N. Security Council today dls- The children la u g h ^ and things." he said. Modem char ■ v .tl cusseg ways to end the Persian Gulf Related stories smiled as the storyteller acters, such as Rambo, don’t war, one day after the United States on page 7 weaved his carefully chosen teach children much about and the Soviet Union stressed the words, creating an image that P compassion, he said. importance of a common front in became a presence as the story He prefers to" tell his own stopping the conflict. grew longer. stories because stories of old Security Council President Obed 20 cease-fire resolution. But reports published today said “ Alfred the Ant" was the relate the values of the time Asamoah of Ghana summoned the big-city insect and Jehan Cle they were written. -

Films Refusés, Du Moins En Première Instance, Par La Censure 1917-1926 N.B

Films refusés, du moins en première instance, par la censure 1917-1926 N.B. : Ce tableau dresse, d’après les archives de la Régie du cinéma, la liste de tous les refus prononcés par le Bureau de la censure à l’égard d’une version de film soumise pour approbation. Comme de nombreux films ont été soumis plus d’une fois, dans des versions différentes, chaque refus successif fait l’objet d’une nouvelle ligne. La date est celle de la décision. Les « Remarques » sont reproduites telles qu’elles se trouvent dans les documents originaux, accompagnées parfois de commentaires entre [ ]. 1632 02 janv 1917 The wager Metro Immoral and criminal; commissioner of police in league with crooks to commit a frame-up robbery to win a wager. 1633 04 janv 1917 Blood money Bison Criminal and a very low type. 1634 04 janv 1917 The moral right Imperial Murder. 1635 05 janv 1917 The piper price Blue Bird Infidelity and not in good taste. 1636 08 janv 1917 Intolerance Griffith [Version modifiée]. Scafold scenes; naked woman; man in death cell; massacre; fights and murder; peeping thow kay hole and girl fixing her stocking; scenes in temple of love; raiding bawdy house; kissing and hugging; naked statue; girls half clad. 1637 09 janv 1917 Redeeming love Morosco Too much caricature on a clergyman; cabaret gambling and filthy scenes. 1638 12 janv 1917 Kick in Pathé Criminal and low. 1639 12 janv 1917 Her New-York Pathé With a tendency to immorality. 1640 12 janv 1917 Double room mystery Red Murder; robbery and of low type. -

From Curtis to Eleanor, What Splendor In-Between; from Curtis to Eleanor, Was It Only a Dream

From Curtis Ken Curtis To Eleanor Eleanor Parker An exercise in Proximity and Happenstance by Clark N. Nelson, Sr. (May be updated periodically: Last update 06-07-20) 1 Prelude The quality within several photographs, in particular, those from the motion pictures ‘Untamed Women’, ‘Santa Fe Passage’, and ‘The King and Four Queens’, might possibly prove questionable, yet were included based upon dwindling sources and time capsule philosophy. Posters and scenes relevant to the motion picture ‘Only Angels Have Wings’ from 1939 are not applicable to my personal accounts, yet are included based upon the flying sequences above Washington County by renowned all-ratings stunt pilot Paul Mantz. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions as well as those providing encouragements toward completion of this document: Emma Fife Pete Ewing LaRee Jones Heber Jones Eldon Hafen George R. Cannon. Jr. Winona Crosby Stanley Don Hafen Jim Kemple Rod Kulyk Kelton Hafen Bert Emett 2 Index Page Overture 4 Birth of a Movie Set 4 Preamble 8 Once Upon a Dime 19 Recognize this 4 year-old? 20 Rex’s Fountain 9 Dick’s Cafe 15 The Films Only Angels Have Wings 22 Stallion Canyon 26 Untamed Women 29 The Vanishing American 46 The Conqueror 51 Santa Fe Passage 71 Run of the Arrow 90 The King and Four Queens 97 3 Overture From the bosom of cataclysmic event, prehistoric sea bed, riddles in sandstone; petrified rainbows, tectonic lava flow; a world upside down; cataclysmic brush strokes, portraits in cataclysm; grandeur in script, grandeur in scene.