Mutual Aesthetics Joseph D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Voice and the Silent Cinema. PUB DATE Apr 75 NOTE 23P.; Paper Presented at the Society Tor Cinema Studies Conference (New York City, April 1975)

i t i DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 527 CS 501 036 AUTHOR Berg, Charles M. TITLE The Human Voice and the Silent Cinema. PUB DATE Apr 75 NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at the Society tor Cinema Studies Conference (New York City, April 1975) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.58 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Audiovisual Communication; Communication (Thought Transfer); *Films; *Film Study; Higher Education; *History; *Sound Films; Visual Literacy ABSTRACT This paper traces the history of motion pictures from Thomas Edison's vision in 1887 of an instrument that recorded body movements to the development cf synchronized sound-motion films in the late 1920s. The first synchronized sound film was made and demonstrated by W. K. L. Dickson, an assistant to Edison, in 1889. The popular acceptance of silent films and their contents is traced. through the development of film narrative and the use of music in the early 1900s. The silent era is labeled as a consequence of technological and economic chance and this chance is made to account for the accelerated development of the medium's visual communicative capacities. The thirty year time lapse between the development of film and the -e of live human voices can therefore be regarded as the critical stimuli which pushed the motion picture into becoming an essentially visual medium in which the audial channel is subordinate to and supportive of the visual channel. The time lapse also aided the motion picture to become a medium of artistic potential and significance. (RB) U SOEPARTME NT OF HEALTH. COUCATION I. WELFARE e NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF 4 EOUCATION D, - 1'HA. -

February 2009 I COMIN’AT ‘CHA!I 2008 SASS Southwest Regional Match

MercantileEXCITINGSee section our (starting on page 94) NovemberNovemberNovember 2001 2001 2001 CowboyCowboyCowboy ChronicleChronicleChronicle PagePagePage 111 The Cowboy Chronicle~ The Monthly Journal of the Single Action Shooting Society ® Vol. 22 No. 2 © Single Action Shooting Society, Inc. February 2009 i COMIN’AT ‘CHA!i 2008 SASS Southwest Regional Match By Ringo Fire, SASS Life #46037 and Buffy Lo Gal, SASS Life #46039 ES!!! It’s finally here!!! HIGHLIGHTS start on page 73 I’ve been waiting … what?!? It’s over??? check out the vendors, and get ready Y Bull Shoals, SASS for side matches in the afternoon. #25400, summed it up when he said, Side matches were the routine pis- “When you check in on Thursday it’s tol, rifle, and shotgun speed match- like getting on a non-stop carnival es, along with derringer, pocket pis- ride, and when you open your eyes, tol, and long-range events. it’s already Sunday, and it’s over!” Following the side matches was That’s pretty much the way it a Wild Bunch match, under the went at Comin’ at ‘Cha, the 2008 direction and coordination of Goody, SASS Southwest Regional. It was SASS #26190, and Silver Sam, SASS four days of full-tilt boogie, non-stop #34718. That evening was the Cow- action, and fun. T-Bone Dooley, SASS boy Garage Sale (although some #36388, has always called Comin’ at pards did some early shopping while ‘Cha a party with a shoot thrown in, side matches were being shot) where and this year was no different. Okay, folks could try to sell stuff they had the theme was different … Mardi laying around the house or RV they Gras!!! And this year it was the no longer wanted, followed by the SASS Southwest Regional Cham- first night of Karaoke and the accom- pionship … but, you know what I Mardi Gras was the match theme … the festivities started during opening panying general rowdiness. -

A Sound Selection

Alexander Horwath A Sound Selection Film Curatorship, Canonization, and a Film Program I am aware that the sort of wordplay represented by the title of this two-part program only works in English. Nevertheless, I would like to hope that even for non-English readers more than one wave of meaning will spill back and forth between the title and the films I have selected. The act of looking at and listening to these works will be the sounding board for what I have in mind. For one thing, the title not only relates to the films I have chosen, but also to the mission I’ve been given as a participant in this year’s Film Mutations festival: to contribute in a more general manner to a discussion about the ethics, aesthetics and politics of (film) curatorship. Considering how rarely curators have to justify or legitimate their choices (compared to other professions such as doctors, judges, politicians – or artists), one might ask by which standards a sound selection should be measured. To list only a few equivalents for the adjective sound : When is a selection of films ever “proper” or “solid” or “healthy” or “substantiated” or, of all things, “curative”? As far as I’m concerned, taking language seriously (including, of course, its playful uses) is the first step towards taking film and film curatorship seriously as well (including their playful uses). I have therefore tried to make a solid, substantiated and curative selection. One of several issues in the (still relatively small) field of film curatorial studies is the question of the combined program – that “feature-length” entity which consists of several “short” films. -

Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI)

Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) The Department of English RAJA N.L. KHAN WOMEN’S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Midnapore, West Bengal Course material- 2 on Techniques of Cinematography (Some other techniques) A close-up from Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) For SEC (English Hons.) Semester- IV Paper- SEC 2 (Film Studies) Prepared by SUPROMIT MAITI Faculty, Department of English, Raja N.L. Khan Women’s College (Autonomous) Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. April, 2020. 1 Dept. of English, RNLKWC--SEM- IV—SEC 2—Techniques of Cinematography: 2 (SUPROMIT MAITI) Techniques of Cinematography (Film Studies- Unit II: Part 2) Dolly shot Dolly shot uses a camera dolly, which is a small cart with wheels attached to it. The camera and the operator can mount the dolly and access a smooth horizontal or vertical movement while filming a scene, minimizing any possibility of visual shaking. During the execution of dolly shots, the camera is either moved towards the subject while the film is rolling, or away from the subject while filming. This process is usually referred to as ‘dollying in’ or ‘dollying out’. Establishing shot An establishing shot from Death in Venice (1971) by Luchino Visconti Establishing shots are generally shots that are used to relate the characters or individuals in the narrative to the situation, while contextualizing his presence in the scene. It is generally the shot that begins a scene, which shoulders the responsibility of conveying to the audience crucial impressions about the scene. Generally a very long and wide angle shot, establishing shot clearly displays the surroundings where the actions in the Prepared by: Supromit Maiti. -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

Wide Shot (Or Establishing Shot) Medium Shot Close-Up Extreme

Definitions: Wide Shot (or Establishing Shot) Medium Shot Close-up Extreme Close-up Pan –Right or left movement of the camera Tilt –Up or down movement of the camera Zoom –Change in focal length (magnification) of the lens V/O –Voice-over, narration not synchronized with video SOT –Sound on Tape, Interview audio synchronized with video B-Roll -Refers to the earlier days of film when you had two rolls of film – A and B – and you had to edit them together. A-roll is the main subject of your shot, with audio such as an interview with someone or SOT (Sound on Tape synchronized with the video). B-roll is the background video for your film, often just video over which you’ll lay an audio track (such as the person talking in the A-roll). Nat Sound (Wild Sound) –Natural sound recorded with B-Roll This is video that has some natural background noise – traffic on a street, birds chirping in a park, etc. This audio can add depth and impact to a two-dimensional video tape. 2-Shot –Shot of the interview subject and the person asking the questions Reverse Angle –Straight-on shot of the person asking the questions Use a Tripod Use a tripod to get a steady shot, particularly if you’re shooting something that is not moving or a formal interview. Shaky video, especially in close-ups, can cause the viewer to become dizzy, even nauseous. If you don’t have a tripod or you’re doing a shot where you’ll have to move quickly, then find something to steady your camera – i.e. -

National Box Office Digest Annual (1940)

Ho# Ujjfice JbiaeAt Haui: «m JL HE MOST IMPORTANT NEWS of many moons to this industry is the matter-of-fact announcement by Technicolor that it will put into effect a flat reduction of one cent a foot on release prints processed after August 1st. "There is a great industrial story of days and nights and months and years behind the manner in which Dr. Kalmus and his associates have boosted the quality and service of color to the industry, beaten down the price step by step, and maintained a great spirit of cooperation with production and exhibition. TECHNICOLOR MOTION PICTURE CORPORATION HERBERT T. KALMUS, President , 617 North La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, Subscription Rate, $10.00 Per ■Ml ^Ite. DIGEST ANNUAL *7lie. 1/ea>i WcM. D OMESTIC box office standings take on values in this year of vanished foreign markets that are tremendous in importance. They are the only ratings that mean anything to the producer, director, player, and exhibitor. Gone—at least for years to come—are the days when known box office failures in the American market could be pushed to fabulous income heights and foisted on the suffering American exhibitor because of a shadowy "for¬ eign value.” Gone are the days—and we hope forever—when producers could know¬ ingly, and with "malice aforethought,” set out on the production of top budgetted pictures that would admittedly have no appeal to American mass audiences, earn no dimes for American exhibitors. All because of that same shadowy foreign market. ^ ^ So THE DIGEST ANNUAL comes to you at an opportune time. -

3. Groundhog Day (1993) 4. Airplane! (1980) 5. Tootsie

1. ANNIE HALL (1977) 11. THIS IS SPINAL Tap (1984) Written by Woody Allen and Marshall Brickman Written by Christopher Guest & Michael McKean & Rob Reiner & Harry Shearer 2. SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959) Screenplay by Billy Wilder & I.A.L. Diamond, Based on the 12. THE PRODUCERS (1967) German film Fanfare of Love by Robert Thoeren and M. Logan Written by Mel Brooks 3. GROUNDHOG DaY (1993) 13. THE BIG LEBOWSKI (1998) Screenplay by Danny Rubin and Harold Ramis, Written by Ethan Coen & Joel Coen Story by Danny Rubin 14. GHOSTBUSTERS (1984) 4. AIRplaNE! (1980) Written by Dan Aykroyd and Harold Ramis Written by James Abrahams & David Zucker & Jerry Zucker 15. WHEN HARRY MET SALLY... (1989) 5. TOOTSIE (1982) Written by Nora Ephron Screenplay by Larry Gelbart and Murray Schisgal, Story by Don McGuire and Larry Gelbart 16. BRIDESMAIDS (2011) Written by Annie Mumolo & Kristen Wiig 6. YOUNG FRANKENSTEIN (1974) Screenplay by Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Screen Story by 17. DUCK SOUP (1933) Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks, Based on Characters in the Novel Story by Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby, Additional Dialogue by Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley Arthur Sheekman and Nat Perrin 7. DR. STRANGELOVE OR: HOW I LEARNED TO STOP 18. There’s SOMETHING ABOUT MARY (1998) WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB (1964) Screenplay by John J. Strauss & Ed Decter and Peter Farrelly & Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Peter George and Bobby Farrelly, Story by Ed Decter & John J. Strauss Terry Southern 19. THE JERK (1979) 8. BlaZING SADDLES (1974) Screenplay by Steve Martin, Carl Gottlieb, Michael Elias, Screenplay by Mel Brooks, Norman Steinberg Story by Steve Martin & Carl Gottlieb Andrew Bergman, Richard Pryor, Alan Uger, Story by Andrew Bergman 20. -

Film from Both Sides of the Pacific Arw

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2012 Apr 26th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific arW Avery Fischer Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Fischer, Avery, "Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific arW " (2012). Young Historians Conference. 9. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2012/oralpres/9 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific War Avery Fischer Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 202: History of the United States Portland State University March 21, 2012 Painting the Enemy in Motion: Film from both sides of the Pacific War On December 7, 1941, American eyes were focused on a new enemy. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, no longer were Americans concerned only with the European front, but suddenly an attack on American soil lead to a quick chain reaction. By the next day, a declaration of war was requested by President Roosevelt for "a date that will live on in infamy- the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan .. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

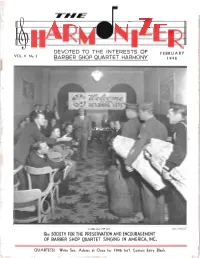

Devoted to the Interests of Barber Shop Quartet

DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF FEBRUARY VOL. V. No.3 BARBER SHOP QUARTET HARMONY 1946 PUBLISHED BY DICK STURGES '6he SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT OF BARBER SHOP QUARTET SINGING IN AMERICA, INC. QUARTETS! Write Sec. Adams at Once for 1946 Int'!. Contest Entry Blank. 2 fYlu HARMONIZER Costuming and Showmanship Are our quartets losing "color" b)' getting too far away from old ways and too far into new ways-in the matter of costuming? We think per --------- haps they are and we have asked a Published quarterly by the International Officers and the other members of few opmions on the subject. Here's the International Bo;.trd of Directors of the Society for the Preservation and one, in part, from one of SPEB's Vice Encouragement of Barber Shop Quartet Sing'jng in America, Inc., for free Presidents, distribution to the members of the Society. "For the sake of originality, why --------- can't more of our quartets do as the VOLUME V FEBRUARY, 1946 No, 3 Slap Happies of Saginaw did. They 35c per Copy bought green slacks (that can be worn anywhere). Then they located four used tuxedo jackets and some Carroll P. Adams - Editor and Business Manager green silk and paid a seamstress a few dollars to cover the lapels and 18270 Grand River Avenue, Detroit 23, Michigan cuffs with the silk. With top hats, Phone: VE 7-7300 just past their prime, and colorful ---_. flowing ties, the boys came up with CONTRIBUTING EDITORS fine looking costumes at a net ex O. C. CASH GE:ORGE W.