The 2019 State Energy Efficiency Scorecard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

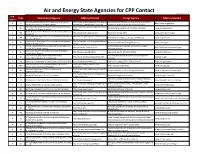

State Agency CPP SIP.Xlsx

Air and Energy State Agencies for CPP Contact Draft November 2015 EPA State Environment Agency Address/Contact Energy Agency Address/Contact Region Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental http://www.ct.gov/deep/cwp/view.asp?a= Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental 1 CT http://www.ct.gov/pura Protection; Bureau of Air Management 2684&q=321758&deepNav_GID=1619 Protection; Public Utilities Regulatory Authority Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection; http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/mass 1 MA Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources www.mass.gov/doer/ Air Quality and Climate Programs dep/air/ Maine Department of Environmental Protection; Bureau of 1 ME http://www.maine.gov/dep/air Governor's Energy Office www.maine.gov/energy/ Air Quality New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services; Air http://des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/ai 1 NH New Hampshire Office of Energy and Planning www.nh.gov/oep/ Resources Division r/ Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management; http://www.dem.ri.gov/programs/benviro 1 RI Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources www.riseo.ri.gov Office of Air Resources n/air/ Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation; Air Vermont Public Service Dept, Planning and Energy 1 VT http://www.anr.state.vt.us/air http://publicservice.vermont.gov/ Quality and Climate Division Resources Division New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection; 2 NJ http://www.nj.gov/dep/daq/ New Jersey Bureau of Public Utilities www.bpu.state.nj.us Division of Air Quality New York State -

US Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report

U.S. Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report: State of the Wind Industry in the Regions Ruth Baranowski, Frank Oteri, Ian Baring-Gould, and Suzanne Tegen National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Technical Report NREL/TP-5000-62942 March 2016 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 U.S. Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report: State of the Wind Industry in the Regions Ruth Baranowski, Frank Oteri, Ian Baring-Gould, and Suzanne Tegen National Renewable Energy Laboratory Prepared under Task No. WE14.BB01 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-5000-62942 Golden, CO 80401 March 2016 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. -

Standards and Requirements for Solar Equipment, Installation, and Licensing and Certification a Guide for States and Municipalities

SUSTAINABLE SOLAR EDUCATION PROJECT Beren Argetsinger, Keyes&FoxLLP•BenjaminInskeep,EQResearchLLC Beren Argetsinger, A GuideforStatesandMunicipalities and LicensingCertification for SolarEquipment,Installation, Standards andRequirements FEBRU A RY 2017 RY © B igstock/ilfede SUSTAINABLE SOLAR EDUCATION PROJECT ABOUT THIS GUIDE AND THE SUSTAINABLE SOLAR EDUCATION PROJECT Standards and Requirements for Solar Equipment, Installation, and Licensing and Certification: A Guide for States and Municipalities is one of six program guides being produced by the Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA) as part of its Sustainable Solar Ed- ucation Project. The project aims to provide information and educational resources to help states and municipalities ensure that distributed solar electricity remains consumer friendly and its benefits are accessible to low- and moderate-income households. In ad- dition to publishing guides, the Sustainable Solar Education Project will produce webinars, an online course, a monthly newsletter, and in-person training on topics related to strengthening solar accessibility and affordability, improving consumer information, and implementing consumer protection measures regarding solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. More information about the project, including a link to sign up to receive notices about the project’s activities, can be found at www.cesa.org/projects/sustainable-solar. ABOUT THE U.S. DEpaRTMENT OF ENERGY SUNSHOT INITIATIVE The U.S. Department of Energy SunShot Initiative is a collaborative national effort that aggressively drives innovation to make solar energy fully cost-competitive with traditional energy sources before the end of the decade. Through SunShot, the Energy Department supports efforts by private companies, universities, and national laboratories to drive down the cost of solar electricity to $0.06 per kilowatt-hour. -

Assessment of the Economic Potential of Distributed Wind in Colorado

Assessment of the Economic Potential of Distributed Wind in Colorado, Minnesota, and New York Kevin McCabe, Benjamin Sigrin, Eric Lantz, and Meghan Mooney National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-70547 January 2018 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Assessment of the Economic Potential of Distributed Wind in Colorado, Minnesota, and New York Kevin McCabe, Benjamin Sigrin, Eric Lantz, and Meghan Mooney National Renewable Energy Laboratory Suggested Citation McCabe, Kevin, Benjamin Sigrin, Eric Lantz, and Meghan Mooney. 2018. Assessment of the Economic Potential of Distributed Wind in Colorado, Minnesota, and New York. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-6A20-70547. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/ 70547.pdf. NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-6A20-70547 Golden, CO 80401 January 2018 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. -

Marine Energy in the United States: an Overview of Opportunities

Marine Energy in the United States: An Overview of Opportunities Levi Kilcher, Michelle Fogarty, and Michael Lawson National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5700-78773 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC February 2021 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Marine Energy in the United States: An Overview of Opportunities Levi Kilcher, Michelle Fogarty, and Michael Lawson National Renewable Energy Laboratory Suggested Citation Kilcher, Levi, Michelle Fogarty, and Michael Lawson. 2021. Marine Energy in the United States: An Overview of Opportunities. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL/TP-5700-78773. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/78773.pdf. NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Technical Report Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy NREL/TP-5700-78773 Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC February 2021 This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. 15013 Denver West Parkway Golden, CO 80401 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NOTICE This work was authored by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Water Power Technologies Office. -

Energy Conservation Standards for Manufactured Housing. Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

This document, concerning manufactured housing is an action issued by the Department of Energy. Though it is not intended or expected, should any discrepancy occur between the document posted here and the document published in the Federal Register, the Federal Register publication controls. This document is being made available through the Internet solely as a means to facilitate the public's access to this document. [6450-01-P] DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY 10 CFR Part 460 [Docket No. EERE-2009-BT-BC-0021] RIN: 1904-AC11 Energy Conservation Standards for Manufactured Housing AGENCY: Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Department of Energy. ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking and public meeting. SUMMARY: The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) today publishes a proposed rule to implement section 413 of the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, which directs DOE to establish energy conservation standards for manufactured housing. DOE proposes to establish energy conservation standards for manufactured housing based on the negotiated consensus recommendations of the manufactured housing working group (MH working group). The MH working group’s recommendations were based on the 2015 edition of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC), the impact of the IECC on the purchase price of manufactured housing, total lifecycle construction and operating costs, factory design and construction techniques unique to manufactured housing, and the current construction and safety standards set forth by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1 DATES: DOE will hold a public meeting on Wednesday, July 13, 2016 from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. in Washington, DC. -

U.S. Geological Survey Energy and Wildlife Research Annual Report For

U.S. Geological Survey—Energy and Wildlife Research Annual Report for 2017 Circular 1435 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Top: Wind energy facility in White Pine County, Nevada (Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]), and bats flying at night (Ann Froschaue, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). Middle: Utility-scale solar array on Moapa Band of Paiutes Indian land, southern Nevada (U.S. Department of Energy), and desert tortoise near Palm Springs, California (Jeffrey Lovich, USGS). Bottom: Glen Canyon Dam hydroelectric facility at night, Arizona (Thomas Ross Reeve, Bureau of Reclamation), and razorback sucker (Melanie Fischer, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service). U.S. Geological Survey—Energy and Wildlife Research Annual Report for 2017 Edited by Mona Khalil Agave plants at a U.S. Department of Agriculture experimental plot site near Phoenix, Arizona. The U.S. Geological Survey, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Arid Land Agricultural Research Center and Ohio University, is conducting tests for the potential production of agave biofuel. Photograph by Sasha Reed, U.S. Geological Survey. Circular 1435 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior RYAN K. ZINKE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey William H. Werkheiser, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2017 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit https://www.usgs.gov/ or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit https://store.usgs.gov. -

BUILD BACK BETTER, FASTER How a Federal Stimulus Focusing on Clean Energy Can Create Millions of Jobs and Restart America’S Economy © Dennis Schroeder/NREL

BUILD BACK BETTER, FASTER How a federal stimulus focusing on clean energy can create millions of jobs and restart America’s economy © Dennis Schroeder/NREL PRODUCED FOR: IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................................................................3 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................6 Energy Efficiency Economic Stimulus Impacts ......................................................................................................8 Introduction & Policy Overview ...................................................................................................................................................8 Energy Efficiency Stimulus Model Output .................................................................................................................................9 Renewable Energy Economic Stimulus Impacts...................................................................................................11 Introduction & Policy Overview ................................................................................................................................................ 11 Renewable Energy Stimulus Model Output ........................................................................................................................... -

2009 NGA Winter Meeting

1 1 NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 2 * * * 3 WINTER MEETING - OPENING PLENARY SESSION 4 * * * 5 J.W. MARRIOTT HOTEL 6 Salon III 7 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. 8 Washington, D.C. 9 * * * 10 Saturday, February 21, 2009 11 11:40 a.m. 12 13 The above-entitled matter convened on 14 Saturday, February 21, 2009 at 11:40 a.m., NGA Chair Governor 15 Edward G. Rendell, presiding. 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 2 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 (11:40 p.m.) 3 GOVERNOR RENDELL: Good afternoon, 4 everyone. It's my pleasure to call to order, the 5 2009 Winter Meeting of the National Governors 6 Association. May I have a motion for the adoption of 7 the Rules of Procedure for this meeting? 8 VOICES: So moved. 9 GOVERNOR RENDELL: Second? 10 VOICES: Second. 11 GOVERNOR RENDELL: All in favor, say aye. 12 (Chorus of ayes.) 13 GOVERNOR RENDELL: The ayes have it. Part 14 of the new rules require that any governor who wants 15 to a submit a new policy or resolution for adoption 16 at this meeting, will need a three-fourths vote to 17 suspend the Rules to do so. 18 If you want to do that, please submit a 19 proposal in writing to David Quam of the NGA staff, 20 by 5:00 p.m. Sunday, February 22nd. It's now my 21 pleasure to introduce our newest colleagues, five of 22 the six, I think, are here and present today. -

Sharing Success

BIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNES MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHO OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO REPUBLIC OF PALAU RHODE I S L A N D SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VERMONT VIRGIN ISLANDS GINIA WASHINGTON WEST VIRGINIA WISCONSIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA AMERICAN SAMOA ARIZONA ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO NORTHERN M ANA ISLANDS CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO ILLINOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MA MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRASKA NEVADA NEWHAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW Y NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO REPUBLIC OF PALAU RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH DAKOTA T NESSEE TEXAS UTAH VERMONT VIRGIN ISLANDS VIRGINIA WASHINGTON WEST VIRGINIA WISCONSIN WYOMING ALABAMA ALASKA AMERICAN SAMOA ARIZ ARKANSAS CALIFORNIA COLORADO NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS CONNECTICUT DELAWARE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FLORIDA GEORGIA GUAM HAWAII IDAHO NOIS INDIANA IOWA KANSAS KENTUCKY LOUISIANA MAINE MARYLAND MASSACHUSETTS MICHIGAN MINNESOTA MISSISSIPPI MISSOURI MONTANA NEBRA NEVADA NEW HAMPSHIRE NEW JERSEY NEW MEXICO NEW YORK NORTH CAROLINA NORTH DAKOTA OHIO OKLAHOMA OREGON PENNSYLVANIA PUERTO RICO REP LIC OF PALAU RHODE ISLAND SOUTH CAROLINA SOUTH DAKOTA TENNESSEE TEXAS UTAH VERMONT VIRGIN ISLANDS VIRGINIA WASHINGTON -

Energy Law As Federal Ceremony

01CONLAN -- FINAL 6/18/2010 6:46 AM ARTICLE ―O, FOR A MUSE OF FIRE‖: ENERGY LAW AS FEDERAL CEREMONY James P. Conlan* ABSTRACT .................................................................................... 2 I. THE ELEMENTS OF IMPERIAL CEREMONY ................................... 2 II. THE LEGAL REALITY OF OIL ....................................................... 5 III. THE ENERGY POLICY ACT OF 2005 (―EPACT‖) ........................ 11 IV. THE ENERGY INDEPENDENCE AND SECURITY ACT OF 2007 (EISA) ................................................................................. 19 V. DISTINGUISHING CEREMONIAL POSTURE FROM JURISDICTION ...................................................................... 24 VI. IMPERIAL POSTURING IN THE EPACT AND EISA ..................... 31 VII. THE EFFECT OF EISA ON THE STATES ................................... 35 VIII. THE PROPER REACTION OF PUERTO RICO TO FEDERAL ENERGY LAW ....................................................................... 39 IX. THE NEED FOR LOCAL LEGISLATION ....................................... 50 * James Peter Conlan, J.D., Ph.D., is a professor of English at the flagship campus of University of Puerto Rico where he teaches medieval and Renaissance English literature at the undergraduate and graduate levels as part of his regular charge and Early Modern English history by invitation. He holds a B.A. in history from Williams College, an M.A. in English from the University of Virginia, a Ph.D. in English from the University of California, Riverside, and a J.D. from -

Guide to Purchasing Green Power

Guide to Purchasing Green Power Renewable Electricity, Renewable Energy Certificates, and On-Site Renewable Generation This guide can be downloaded from: https://www.epa.gov/greenpower/guide-purchasing-green-power Office of Air (6202J) EPA430-K-04-015 www.epa.gov/greenpower March 2010 Updated: September 2018 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................v Chapter 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................1-1 Chapter 2 Introducing Green Power ............................................................................................................................2-1 What is Green Power? ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2-3 Introduction to Renewable Energy Certificates ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2-3 Introduction to the Voluntary Market .......................................................................................................................................... 2-5 Certification and Verification .........................................................................................................................................................