How States Count Polluting Energy Sources As Renewable (Food & Water Watch Study)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Agency CPP SIP.Xlsx

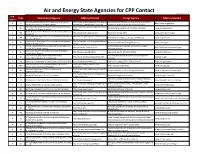

Air and Energy State Agencies for CPP Contact Draft November 2015 EPA State Environment Agency Address/Contact Energy Agency Address/Contact Region Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental http://www.ct.gov/deep/cwp/view.asp?a= Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental 1 CT http://www.ct.gov/pura Protection; Bureau of Air Management 2684&q=321758&deepNav_GID=1619 Protection; Public Utilities Regulatory Authority Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection; http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/mass 1 MA Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources www.mass.gov/doer/ Air Quality and Climate Programs dep/air/ Maine Department of Environmental Protection; Bureau of 1 ME http://www.maine.gov/dep/air Governor's Energy Office www.maine.gov/energy/ Air Quality New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services; Air http://des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/ai 1 NH New Hampshire Office of Energy and Planning www.nh.gov/oep/ Resources Division r/ Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management; http://www.dem.ri.gov/programs/benviro 1 RI Rhode Island Office of Energy Resources www.riseo.ri.gov Office of Air Resources n/air/ Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation; Air Vermont Public Service Dept, Planning and Energy 1 VT http://www.anr.state.vt.us/air http://publicservice.vermont.gov/ Quality and Climate Division Resources Division New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection; 2 NJ http://www.nj.gov/dep/daq/ New Jersey Bureau of Public Utilities www.bpu.state.nj.us Division of Air Quality New York State -

POWER GENERATION Kohler Power President Talks About Liebherr, Clarke Energy, What's Ahead for the Global Generator and Engine

POWER GENERATION Kohler Power president talks about Liebherr, Clarke Energy, what’s ahead for the global generator and engine manufacturer. By Mike Brezonick ne of the key architects of the company’s growth strategy is Tom Cromwell, Opresident of Kohler Power. A vice president at heat transfer specialist Modine Manufacturing before coming to Kohler in 2009, Cromwell served as president of gasoline and then global engine business before assuming leadership of the company’s development standpoint specific to overall engine and power generation segments in 2009. Diesel Progress recently talked G-drive engines. If you think about with Cromwell in his office in Kohler, Wis. most generator applications, it uses an engine that was developed for something In 2016, Kohler partnered these units. They’ve continued to add else and at some point, the engine is with Liebherr on a new range more and more capacity into both the retrofitted to be an acceptable generator of generator drive engines Bulle and Colmar facilities to support engine? and then launched the KD our growth. Everything that has been launched by series generator sets based They’ve done the engine development Liebherr so far for these large platform on those engines. Where work on the mining and construction engines has been for generators. might that relationship go in application for those engines and We changed where the turbos are the future? we’ve helped them from an engine configured and a lot about the base Liebherr’s capability, from a development standpoint, has been outstanding. They have strong “With the KD series, engineering capabilities; strong technical capabilities and they’ve invested a lot Kohler owns every into the partnership. -

US Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report

U.S. Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report: State of the Wind Industry in the Regions Ruth Baranowski, Frank Oteri, Ian Baring-Gould, and Suzanne Tegen National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. Technical Report NREL/TP-5000-62942 March 2016 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 U.S. Department of Energy Regional Resource Centers Report: State of the Wind Industry in the Regions Ruth Baranowski, Frank Oteri, Ian Baring-Gould, and Suzanne Tegen National Renewable Energy Laboratory Prepared under Task No. WE14.BB01 NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report 15013 Denver West Parkway NREL/TP-5000-62942 Golden, CO 80401 March 2016 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. -

WORKING TOGETHER Clarke's 2015 Sustainability Report

WORKING TOGETHER Clarke's 2015 Sustainability Report ii G4-1, G4-2 It is my pleasure to introduce our seventh Sustainability Report. This report highlights our work in 2015 and measures our progress toward our 2020 Sustainability Goals. 2015 was a year of working together. It was a year of collaboration and partnership— throughout all areas of our business and in all of our endeavors. Employees came together to share stories of their successes and to explore solutions to their challenges. Suppliers and partners helped us to eliminate unnecessary waste and improve efficiencies in our service operations and manufacturing processes. Our scientific and regulatory teams articulated a “road map” to guide the discovery, development and commercialization of our greener chemistry, Next Gen products. Those same teams partnered with local schools to educate and inspire the next generation of environmental and sustainability minded scientists. We worked with and within our local communities to give back and to demonstrate our care for people and for the planet. In 2015, we engaged with our stakeholders—employees, customers, suppliers, and partners—to identify the issues and opportunities that matter most. And with this insight, we are able to refine our focus and concentrate our efforts on providing high quality, innovative and effective products and services that address public health issues and improve the quality of inland waterways. As the year came to a close, the importance of our work was reinforced with the emergence of new mosquito-borne diseases throughout the world. These emerging new threats remind us of the profound obligation—and the challenge—that we have to take steps today to ensure a sustainable future for our environment, our employees and our business, and for our global community. -

Landfill Gases Landfill Gases Landfill Gas Landfill Gas Collection

Landfill Gases Landfill Gases Landfill Gas Landfill Gas Collection Landfill gas is created during the For a landfill restoration that prevents Clarke Energy is the authorised distributor and service anaerobic decomposition of organic greenhouse gas from migrating partner for GE Energy’s gas engine division in a growing substances in municipal solid waste into the atmosphere while avoiding number of countries across the world. In addition to (MSW), commercial and industrial offensive smells and smouldering providing high-efficiency, reliable gas engines we combine (C&I) wastes and other fires, the gas must be continuously biodegradable waste streams. extracted under controlled conditions. this with the expertise and resources to deliver unbeatable Depending upon the landfill design Perforated tubes are drilled into the product support. and its management, as well as landfill body and interconnected by waste composition, compaction, a pipework system. Using a blower, Whether your requirement is for the supply of a single gas moisture and several other factors, the gas is sucked from the landfill. engine generator or a complete turnkey power generation thousands of landfills are available A well-designed gas collection facility, we can meet that need. Our ability to add value by worldwide to collect and utilise this system will flexibly capture the gas valuable renewable energy source from various spots and handful high offering an end-to-end service, from initial proposal to for power generation. If landfill gas is temperatures, leachate, condensates reliable long-term maintenance, has led to us becoming a allowed to escape to atmosphere, and air content – thus ensuring a multi-national company with operations in ten countries methane contained within it is a cost-efficient collection as well as across the globe. -

Clarke Energy and INNIO Delivering Flexible Generation to Nova Power & Gas in Romania

PRESS RELEASE: Clarke Energy and INNIO Delivering Flexible Generation to Nova Power & Gas in Romania • Clarke Energy supplies 4 INNIO Jenbacher J620 gas engines to the peaking station project. • Construction is ongoing at power plant located in Campia Turzii, Cluj County. • The project will improve efficiency and stability of power to the Reif Industrial Park. Bucharest, Romania — April 16th 2021 — Construction has begun in Campia Turzii, where Clarke Energy and INNIO are delivering a natural-gas fuelled flexible generation plant to Nova Power & Gas SRL, part of the E-INFRA Group The innovative peaking station project consists of 4 INNIO Jenbacher J620 natural gas engines with a total electric power of 13.4 MW. Two of the engines installed with “fast start” capabilities will be utilised for electricity peaking, designed to help balance the fluctuating power requirements of the electricity grid. This peaking plant will provide balancing services at the request of the Transport and System Operator at times of peak demand. The remaining two engines supplied will deliver electricity to the Reif Industrial Park and will provide improved energy efficiency and stability in the area. The project was an important first sales win for Clarke Energy’s Romanian team following the company’s entry into the market through the acquisition of TEB Energy Business in November 2019. With two existing customers who have previously switched from cogeneration to peaking plants, Nova Power & Gas SRL is now the third natural-gas fuelled peaking station in Romania, all equipped with INNIO Jenbacher gas engines. Mircea Bica, CEO of Nova Power & Gas commented “Câmpia Turzii project is our first investment in next-generation power plant based on natural gas with increased efficiency and high operational flexibility. -

Sustainable Municipal Waste Management in India

Sustainable Municipal Waste Management in India White Paper on Removing Barriers to Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management using Anaerobic Digestion in India Delhi, India 1 Delhi, India CONTENTS Executive summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Authors ................................................................................................................................ 4 Table of acronyms .............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 6 India’s power and energy sector – A Changing Landscape ............................................ 7 Waste and sustainable development goals ...................................................................... 9 Regulatory framework on waste management in india .................................................. 10 Challenges associated with use of bio methanation in treating municipal solid waste20 Policy and regulatory challenges ................................................................................. 20 Financial challenges ...................................................................................................... 21 Project and structural challenges ................................................................................. 22 Technology challenges ................................................................................................ -

Renewable Energy: Wind and Solar

Renewable Energy: Chapter | 19 Wind and Solar ❖ Can Texans harness the wind and sun and even the jobs that go with these energy sources? 600-turbine development across 336,000 Introduction acres of West Texas. Financed by Chinese In late 2009, German utility giant E.ON banks, the development will feature new constructed the world’s largest wind farm in turbines made in China and will bring the tiny West Texas town of Roscoe. The 300 temporary construction jobs and 30 Roscoe wind farm has the capacity to produce permanent jobs to the area. Renewable 781.5 megawatts — enough electricity for energy in Texas is new — and it has already every home in Plano, McKinney and the been globalized. rest of the 265,000 households in Collin These giant wind projects illustrate County. The $1 billion project in Roscoe two key trends: Texas is emerging as took 21 months to complete and employed the capital of renewable energy, and 500 construction workers, who built 627 wind foreign companies are moving fast to take turbines on the fields of 300 property owners advantage. “People in Texas think it has — land that once pumped oil. got to be conventional energy or renewable The wind turbines of West Texas spin at energy. It’s not. It’s both,” said Michael 7 miles per hour. And one turbine produces Webber, an engineering professor at the about as much electricity as 350 households University of Texas at Austin and associate consume in a year. These economics are director of the Center for International attracting more wind turbines to the state, Energy and Environmental Policy. -

Renewable Energy Potential in Texas and Business Opportunities for the Netherlands

Renewable energy potential in Texas and business opportunities for the Netherlands Commissioned by the ministry of Foreign Affairs 2016-2017 Renewable energy potential in Texas and business opportunities for the Netherlands Elène Lenders Wageningen University Environmental Economics and Natural Resources Group, Wageningen, The Netherlands The Netherlands Business Support Office, Houston, Texas, United States of America September 2016 – February 2017 Content 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Research Question ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Method .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Definition of renewable energy ..................................................................................................... 5 1.4. Units .............................................................................................................................................. 5 2. The current market situation for energy in Texas ................................................................................. 6 2.1. An independent electricity grid ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2. The main fuel types supplied ....................................................................................................... -

Texas Wind Industry's Rapid Growth Creates New Challenges

BU S I NES SEX R E V I E W A TBureau of Business Research • IC2 institute •The University of Texas at AustinSFebruary 2010 In the past decade, Texas began to harness in carbon emissions and other harmful by- Texas Wind some of its abundant wind potential and, in products associated with some conventional the process, became an international wind forms of power, decreased dependence on Industry's energy leader. The state currently accounts for foreign oil, and economic revitalization of more than 25 percent of installed wind energy rural areas, to name but a few. As compelling Rapid capacity in the United States (see Table 1). as the arguments for wind energy may be, the But while 2009 brought a new pro-renewable growth of wind energy in Texas hinges upon Growth energy administration in Washington, the industry’s ability to address issues that may increased public awareness and interest in limit future development. green technology, and an ever-expanding Creates New demand for energy, the growth of the state’s For example, although wind energy has been new installed capacity fell below 40 percent touted as a green alternative to traditional Challenges for the first time since 2006 (see Table 2, p. generation, there is growing concern about 2). While the recession-induced credit crunch the environmental impact of development by and falling natural gas prices were two obvious on certain key species. And on the political culprits, Texas faces a host of other challenges as front, while the wind industry successfully Will Furgeson avoided any major setbacks during the 81st Development Manager, it seeks to retain its position atop the domestic Invenergy wind energy market and attract the capital and Legislative Session in 2009, the industry must new jobs that the booming renewable energy navigate through another session in 2011. -

Key Drivers and Dependencies for V2G

D1.1 – Key drivers and dependencies for V2G V2GB WP1 Literature review Dr Bilaal Hussain, Consultant – Insights and Evidence 13 November 2018 Key drivers and dependencies for V2G Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction to Work Package 1 ............................................................................................................. 3 2. Identifying the drivers and dependencies ....................................................................................................... 5 3. Literature review ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 System requirements ................................................................................................................................... 6 Reserve power supply ............................................................................................................... 6 Time of use optimisation ......................................................................................................... -

Remote Power Remote Power Power Generation in Remote Areas Benefits

Remote Power Remote Power Power Generation in Remote Areas Benefits In large sparsely populated countries — Reduced energy costs Clarke Energy is the authorised distributor and service the main electricity grid is typically — Reduced/eliminated partner for GE Energy’s gas engine division in a growing focused around the major centres of transmission losses number of countries across the world. In addition to habitation. This can cause challenges — Highly efficient technology with providing high-efficiency, reliable gas engines we combine for developers looking to build minimal de-rate in locations with facilities away from these localities. high ambient temperatures this with the expertise and resources to deliver unbeatable In those areas not serviced by a main — Turn-key service reduces product support. electricity grid, locally generated operation and maintenance electricity is ideally suited as a cost- expenses Whether your requirement is for the supply of a single gas effective way of meeting the — Standardised design allows engine generator or a complete turnkey power generation surrounding electricity demand rapid design, easy transportation facility, we can meet that need. Our ability to add value by while reducing significant network and flexible installation installation or upgrade costs. — Modular unit configurations allow offering an end-to-end service, from initial proposal to scalability of installed plant reliable long-term maintenance, has led to us becoming a Gas engine-based power plants capacity and cost-effective multi-national company with operations in ten countries generate stable base-load power redundancy levels for across the globe. Our company prides itself on integrity, locally to the remote installation.