Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Diurnal Raptors and Airports

Australian diurnal raptors and airports Photo: John Barkla, BirdLife Australia William Steele Australasian Raptor Association BirdLife Australia Australian Aviation Wildlife Hazard Group Forum Brisbane, 25 July 2013 So what is a raptor? Small to very large birds of prey. Diurnal, predatory or scavenging birds. Sharp, hooked bills and large powerful feet with talons. Order Falconiformes: 27 species on Australian list. Family Falconidae – falcons/ kestrels Family Accipitridae – eagles, hawks, kites, osprey Falcons and kestrels Brown Falcon Black Falcon Grey Falcon Nankeen Kestrel Australian Hobby Peregrine Falcon Falcons and Kestrels – conservation status Common Name EPBC Qld WA SA FFG Vic NSW Tas NT Nankeen Kestrel Brown Falcon Australian Hobby Grey Falcon NT RA Listed CR VUL VUL Black Falcon EN Peregrine Falcon RA Hawks and eagles ‐ Osprey Osprey Hawks and eagles – Endemic hawks Red Goshawk female Hawks and eagles – Sparrowhawks/ goshawks Brown Goshawk Photo: Rik Brown Hawks and eagles – Elanus kites Black‐shouldered Kite Letter‐winged Kite ~ 300 g Hover hunters Rodent specialists LWK can be crepuscular Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Photo: Herald Sun. Hawks and eagles ‐ eagles Large ‐ • Wedge‐tailed Eagle (~ 4 kg) • Little Eagle (< 1 kg) • White‐bellied Sea‐Eagle (< 4 kg) • Gurney’s Eagle Scavengers of carrion, in addition to hunters Fortunately, mostly solitary although some multiple strikes on aircraft Hawks and eagles –large kites Black Kite Whistling Kite Brahminy Kite Frequently scavenge Large at ~ 600 to 800 g BK and WK flock and so high risk to aircraft Photo: Jill Holdsworth Identification Beruldsen, G (1995) Raptor Identification. Privately published by author, Kenmore Hills, Queensland, pp. 18‐19, 26‐27, 36‐37. -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Square-Tailed Kites

Husbandry Guidelines For Square-Tailed Kites Lophoictinia isura Aves: Accipitridae Compiler: Jadan Hutchings Date of Preparation: February 2011 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Captive Animal Certificate III, 1068 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld, Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines for Square – Tailed Kites by Jadan Hutchings 2012 2 Disclaimer The following information was compiled during the studies of Captive Animals Certificate III at Richmond Collage NSW Australia in 2011 and early 2012. Since the husbandry guidelines are the result of student project work, care should be taken in the interpretation of information within this document, no responsibility is assumed for any loss or damage that may result from the use of these guidelines. It is offered to the ASZK Husbandry Manuals Register for the benefit of animal welfare and care. Husbandry guidelines are utility documents and are ‘works in progress’, so enhancements to these guidelines are invited. Husbandry Guidelines for Square – Tailed Kites by Jadan Hutchings 2012 3 TASK / MAINTENANCE CALENDER TASK Jan Feb Mar April May June July Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Breeding QLD QLD QLD QLD Season NSW NSW NSW NSW VIC VIC VIC WA WA WA WA Prior breeding QLD NSW VIC season diet increase WA Nest platform Change Enclosure Non breeding Repairs kites Clean up in Non-breeding Enclosure kites Substrate Non-breeding Change kites Massive Clean Enrichment (Beh/Enviro) Pest Control Distance Examinations Physical Examination Weights Record Keeping WORK HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS The Square-Tailed Kite (Lophoictinia isura) can be a hazard in some circumstances. In the breeding seasons they can get quite defensive and become a hazard to one self. -

A Preliminary Risk Assessment of Cane Toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT

supervising scientist 164 report A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park RA van Dam, DJ Walden & GW Begg supervising scientist national centre for tropical wetland research This report has been prepared by staff of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist (eriss) as part of our commitment to the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research Rick A van Dam Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, Locked Bag 2, Jabiru NT 0886, Australia (Present address: Sinclair Knight Merz, 100 Christie St, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia) David J Walden Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia George W Begg Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia This report should be cited as follows: van Dam RA, Walden DJ & Begg GW 2002 A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT The Supervising Scientist is part of Environment Australia, the environmental program of the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Supervising Scientist Environment Australia GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 Australia ISSN 1325-1554 ISBN 0 642 24370 0 This work is copyright Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Supervising Scientist Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction -

Native Fauna of the Bendigo Creek

R e p t i l e s o f B e n d i g o C r e e k M a m m a l s o f B e n d i g o C r e e k Look out for us in summer . Look out for us at dusk . Native fauna of the Boulenger’s Skink Native Water Rat Bendigo Creek I am one of the most common I’m most active at sunset and in A Family Field Guide skinks in the box-ironbark country. the night until dawn as I dive and I love areas with fallen branches hunt for bugs, yabbies, fish and and leaf litter where my colours frogs. Only the top of my head help me hide. You’ll see me and back can be seen as I swim sunbaking in warmer weather but but my white tail tip might be I’ll scuttle away quickly if scared. easy to spot as I climb on land. Common Long-necked Tortoise Sugar Glider I search in the creek for water I rely on hollows in old gum trees creatures but you may see me to survive but will use nest boxes sunning myself on a snag or rock. if I have to. I sleep during the day I roam overland after heavy rain and hunt up in the trees at night but will pull my neck under my searching for beetles and moths shell or spray you with smelly under bark, sap on trunks and wee if you try to touch me. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

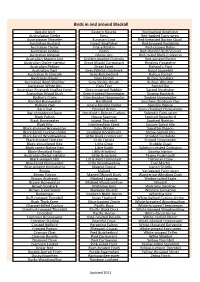

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

A Possible Attack by a Whistling Kite Haliastur Sphenurus on a Sooty Oystercatcher Haematopus Fuliginosus

A Possible Attack by a Whistling Kite Haliastur sphenurus on a Sooty Oystercatcher Haematopus fuliginosus On 30 May 1991 at Pretty Beach, Murramarang National Park, N.S.W. (35°45'S, 150°15'E), I observed a Whistling Kite Haliastur sphenurus attempting to carry away from the ground an adult Sooty Oystercatcher Haematopus fuliginosus. The Kite, which had the Oystercatcher in both feet, was flapping its wings vigorously in an attempt to become airborne. My investigation of the scene may have caused the Kite to abandon its effort, as it released the Oystercatcher and flew off. I then inspected the Oystercatcher which remained prone on the sandy shoreline. It was dead, and freshly oozing blood from wounds around the neck and wings suggested that it may have been the Kite's recent kill. I had observed a pair of Oystercatchers foraging on the beach and adjacent rock platform the previous day, and assume this bird to be one of that pair. After inspecting the kill, I retreated from the scene to see if the Kite would return. However it failed to reappear, and after approximately 20 minutes I left. I returned to the site later in the day and found the Oystercatcher gone. It would appear that at around 800 g (Pringle 1987), the Oystercatcher was too heavy an item for the Kite (also c. 800 g: Baker-Gabb 1984) to lift off the ground, though other species of similar weight have previously been observed in the Kite's diet (Wheeler 1963, Debus 1983, Baker-Gabb 1985, Bollen 1991), some of which may have been taken as carrion. -

Haliastur Sphenurus Whistling Kite

BIRD Haliastur sphenurus Whistling Kite AUS SA AMLR Endemism Residency Head, Fishery Beach).3 - - U - Resident Pre-1983 AMLR filtered records limited to a few records at Morphett Vale, Finniss, Gumeracha and Golden Grove.3 Habitat Found in woodlands, open country and particularly wetlands. Also common around farmland, vineyards and anywhere where carrion can be found (e.g. abattoirs, rubbish dumps and roadsides). Prefers tall trees for nesting.1 Within the AMLR the preferred broad vegetation groups are Grassy Woodland and Riparian.3 Biology and Ecology Soar above the ground, trees and water to search for prey such as carrion and small live animals such as Photo: © Anon. mammals, birds, fish and insects.1 Conservation Significance Breeding season from July to January in the southern The species has been described as 'probably AMLR and March to October in northern areas. Clutch declining' within the AMLR.2 Within the AMLR the size one to three, usually two and incubation period 38 species’ relative area of occupancy is classified as days.1 ‘Very Restricted’. Relative to all AMLR extant species, the species' taxonomic uniqueness is classified as Appears to be monogamous, with some breeding ‘High’.3 pairs remaining in a territory throughout the year actively defending the area around nest. Bulky nest Description platform is built of sticks in a tall tree and may be Medium-sized raptor with a shaggy appearance. reused, growing larger over time. Both sexes build the Light brown head and underparts with pale streaks, nest and incubate the eggs (female does most of the and dark sandy-brown wings with paler undersides. -

Accipitridae Species Tree

Accipitridae I: Hawks, Kites, Eagles Pearl Kite, Gampsonyx swainsonii ?Scissor-tailed Kite, Chelictinia riocourii Elaninae Black-winged Kite, Elanus caeruleus ?Black-shouldered Kite, Elanus axillaris ?Letter-winged Kite, Elanus scriptus White-tailed Kite, Elanus leucurus African Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides typus ?Madagascan Harrier-Hawk, Polyboroides radiatus Gypaetinae Palm-nut Vulture, Gypohierax angolensis Egyptian Vulture, Neophron percnopterus Bearded Vulture / Lammergeier, Gypaetus barbatus Madagascan Serpent-Eagle, Eutriorchis astur Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax uncinatus Gray-headed Kite, Leptodon cayanensis ?White-collared Kite, Leptodon forbesi Swallow-tailed Kite, Elanoides forficatus European Honey-Buzzard, Pernis apivorus Perninae Philippine Honey-Buzzard, Pernis steerei Oriental Honey-Buzzard / Crested Honey-Buzzard, Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard, Pernis celebensis Black-breasted Buzzard, Hamirostra melanosternon Square-tailed Kite, Lophoictinia isura Long-tailed Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis longicauda Black Honey-Buzzard, Henicopernis infuscatus ?Black Baza, Aviceda leuphotes ?African Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda cuculoides ?Madagascan Cuckoo-Hawk, Aviceda madagascariensis ?Jerdon’s Baza, Aviceda jerdoni Pacific Baza, Aviceda subcristata Red-headed Vulture, Sarcogyps calvus White-headed Vulture, Trigonoceps occipitalis Cinereous Vulture, Aegypius monachus Lappet-faced Vulture, Torgos tracheliotos Gypinae Hooded Vulture, Necrosyrtes monachus White-backed Vulture, Gyps africanus White-rumped Vulture, Gyps bengalensis Himalayan -

Book Review Australian Predators of The

December 2015 45 Book Review Australian Predators of the Sky PENNY OLSEN, 2015 National Library of Australia, Canberra. $39.99 Paperback, 207 pages. Penny Olsen’s latest volume bringing together quoted bemoaning the persecution of Wedge- art and birds showcases the work of artists tailed Eagles, Whistling Kites and Brown Falcons, curated at the National Library of Australia. which is a side of him I hadn’t read before. As the title suggests this is also a book about Australian raptors – here including the The species accounts cover 25 diurnal birds of prey Accipitriformes (hawks, eagles and allies), and 9 owls and each is sumptuously illustrated. the Falconiformes (falcons and allies) and the I won’t dwell on the text, which is succinct and Strigiformes (owls). interesting, with notes on the naming of each species, and variously, collecting anecdotes, Introductory chapters document the European geographical notes or interesting aspects of biology discovery of Australia’s raptors and provide a or ecology. First and foremost this book is about brief introduction to their biology and ecology. the artworks displayed, and these are dominated As we would expect from Penny Olsen, the text by four artists: the lithographs of John Gould and is engaging and accessible and manages to both Henry Richter, and the paintings of Ebenezer educate and entertain. I discovered a wealth of Gostelow and Henrik Grønvold. information about both the history of Australian ornithology and bird illustration. The earliest of these were Gould and Richter, working in the 1840s. Their lithographs accompany William Dampier is thought to have been the 26 of the species and probably represent the finest first European to document Australian raptors art in the volume.