Inhabited Places in Aegean Macedonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

Tectonic Structure of Central~Western Attica (Greece) Based on Geophysical Investigations· Preliminary Results

1l£lnlo T~C; EM~VIK~C; rEW'\OVIK~C; ETOIpioC; TOIJ. XXXX, 8ulleLin of the Geolog"ical Society of Greece vol. XXXX, 2007 2007 Proceedings of the 11" International Congress, Athens, May. nponlKa 11°0 IlI£EivovC; ;[uv£oplou, A8rjvo, Maio, 2007 2007 TECTONIC STRUCTURE OF CENTRAL~WESTERN ATTICA (GREECE) BASED ON GEOPHYSICAL INVESTIGATIONS· PRELIMINARY RESULTS 2 Papadopoulos T. D.\ Goulty N. , Voulgaris N. S.1, Alexopoulos J. D.\ Fountoulis 1.1, Kambouris P.t, Karastathis V. 3, Peirce C. 2, ChaHas S,l, Kassaras J. 1, PirH M.t, Goumas G.t, and Lagios E. 1 I National and Kapodistrian University ofAthens, Faculty ofGeology and Geoenvironment, 157~ ZografoH, GREECE ] University ofDurham, Department ofGeological Sciences, UK 3 National Observatmy o/Athens, Geodynamic Institute, 1i8 iO Athens, GREECE Abstract in an effort to investigate the deep geological structure in the broader area ofcen tral-western Attica, that suffered severe damage during the destructive Athens earth 1h quake of September 7 , 1999, the Department of Geophysics-Geothennics of the Faculty ofGeology and Geoenvironment ofAthens University, in collaboration with the Geodynmnic institute ofNational Observatory olAthens and the Department of Geological Sciences of Durham University, carried out a combined geophysical survey. For the first time in Attica, seismiC and gravity geopbysical methods were applied along profiles, in such an extensive scale. Within the ji-amework of this investigation the following tasks were accomplished: a) Three (3) seismic lines of about 30 kilometres oftotal length, two (2) in the area of Thriassiol1 plain and one (1) along the Parnitha-Krioneri-Drosia-Ekali-Dionysos (L'r;is (Attica plain) and b) 338 gravity measurements distributed along eight (8) gravity profiles, four (4) of which in Thriassion plain, three (3) in Petroupoli-Aharnes- Thrakomakedones region (Attica plain) and one (1) along Parnitha-Krioneri-Drosia-Ekali-Dionysos axis (At tica plain). -

Analysis of Historical Events in Greek Occupied Macedonia Part 3

Analysis of historical events in Greek occupied Macedonia Part 3 An interview with Risto Stefov Analysis of historical events in Greek occupied Macedonia An interview with Risto Stefov Part 3 Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2018 by Risto Stefov e-book edition *** April 12, 2018 *** 2 INTERVIEWER – In this interview I would like to ask you some questions about your family and verify some of the things your dad and uncle had said to me in their interviews. Was your grandfather Risto involved in the Illinden Uprising? I remember seeing a photo on someone’s wall. What can you tell me about his life in the village? RISTO – My grandfather Risto was not involved in the Ilinden Uprising because, from what my father had told me, he was not in Macedonia. He was on pechalba (migrant work) but I don’t know where and for how long. He purchased a rifle and wanted to return but the borders were shut and he could not come back in time. He did come back later and brought the rifle with him and gave it to his oldest son Lazo who then used it during the German-Italian- Bulgarian occupation when he was a partisan for a brief period of time before he died in 1943. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949)

JPR Men of the Gun and Men of the State: Military Entrepreneurship in the Shadow of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) Spyros Tsoutsoumpis Abstract: The article explores the intersection between paramilitarism, organized crime, and nation-building during the Greek Civil War. Nation-building has been described in terms of a centralized state extending its writ through a process of modernisation of institutions and monopolisation of violence. Accordingly, the presence and contribution of private actors has been a sign of and a contributive factor to state-weakness. This article demonstrates a more nuanced image wherein nation-building was characterised by pervasive accommodations between, and interlacing of, state and non-state violence. This approach problematises divisions between legal (state-sanctioned) and illegal (private) violence in the making of the modern nation state and sheds new light into the complex way in which the ‘men of the gun’ interacted with the ‘men of the state’ in this process, and how these alliances impacted the nation-building process at the local and national levels. Keywords: Greece, Civil War, Paramilitaries, Organized Crime, Nation-Building Introduction n March 1945, Theodoros Sarantis, the head of the army’s intelligence bureau (A2) in north-western Greece had a clandestine meeting with Zois Padazis, a brigand-chief who operated in this area. Sarantis asked Padazis’s help in ‘cleansing’ the border area from I‘unwanted’ elements: leftists, trade-unionists, and local Muslims. In exchange he promised to provide him with political cover for his illegal activities.1 This relationship that extended well into the 1950s was often contentious. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000-700 BCE Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8588693d Author Kontonicolas, MaryAnn Emilia Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 © Copyright by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE by MaryAnn Kontonicolas Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor John K. Papadopoulos, Chair This research project examines the appearance and proliferation of some of the earliest cremation burials in Europe in the context of the prehistoric north Aegean. Using archaeological and osteological evidence from the region between the Pindos mountains and Evros river in northern Greece, this study examines the formation of death rituals, the role of landscape in the emergence of cemeteries, and expressions of social identities against the backdrop of diachronic change and synchronic variation. I draw on a rich and diverse record of mortuary practices to examine the co-existence of cremation and inhumation rites from the beginnings of farming in the Neolithic period -

Wetlands Management in Northern Greece: an Empirical Survey

water Article Wetlands Management in Northern Greece: An Empirical Survey Eleni Zafeiriou 1,* , Veronika Andrea 2 , Stilianos Tampakis 3 and Paraskevi Karanikola 2 1 Department of Agricultural Development, Democritus University of Thrace, GR68200 Orestiada, Greece 2 Department of Forestry and Management of the Environment and Natural Resources, Democritus University of Thrace, GR68200 Orestiada, Greece; [email protected] (V.A.); [email protected] (P.K.) 3 School of Forestry, Department of Forestry and Natural Environment, Faculty of Agriculture, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-6932-627-501 Received: 29 September 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 13 November 2020 Abstract: Water management projects have an important role in regional environmental protection and socio-economic development. Environmental policies, strategies, and special measures are designed in order to balance the use and non-use values arising for the local communities. The region of Serres in Northern Greece hosts two wetland management projects—the artificial Lake Kerkini and the re-arrangement of Strymonas River. The case study aims to investigate the residents’ views and attitudes regarding these two water resources management projects, which significantly affect their socio-economic performance and produce several environmental impacts for the broader area. Simple random sampling was used and, by the application of reality and factor analyses along with the logit model support, significant insights were retrieved. The findings revealed that gender, age, education level, and marital status affect the residents’ perceived values for both projects and their contribution to local growth and could be utilized in policy making for the better organization of wetland management. -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49 -

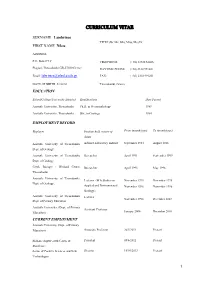

SURNAME DONERT FIRST NAME(S) Karl

CURRICULUM VITAE SURNAME Lambrinos TITLE (Dr. Mr, Mrs, Miss, Ms) Dr. FIRST NAME Nikos ADDRESS P.O. Box 277 C TELEPHONE (+30) 23920 62806 Plagiari, Thessaloniki GR-57500 Greece DAYTIME PHONE (+30) 2310 991201 Email: [email protected] FAX: (+30) 2310 991201 DATE OF BIRTH 21/12/61 Thessaloniki, Greece EDUCATION School/College/University Attended Qualifications Date Passed Aristotle University, Thessaloniki Ph.D. in Geomorphology 1989 Aristotle University, Thessaloniki BSc. in Geology 1984 EMPLOYMENT RECORD Employer Position held, nature of From (month/year) To (month/year) duties Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Adjunct Laboratory Instruct. September 1984 August 1988 Dept. of Geology Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Researcher April 1991 September 1999 Dept. of Geology Greek Biotope / Wetland Center, Researcher April 1995 May 1996 Thessaloniki Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Lecturer (MA Studies in November 1995 November 1995 Dept. of Geology, Applied and Environmental November 1996 November 1996 Geology) Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Lecturer November 1998 December 2003 Dept. of Primary Education Aristotle University (Dept. of Primary Assistant Professor Education) January 2004 December 2010 CURRENT EMPLOYMENT Aristotle University (Dept. of Primary Education) Associate Professor 26/5/2011 Present Hellenic digital-earth Centre of President 08/6/2012 Present Excellence Sector of Positive Sciences and New Director 10/01/2013 Present Technologies 1 Courses Taught: General Geography Photo-interpretation in geosciences GIS and Environment Didactics in Geography Physical Geography Study of the Physical and Social Environment Teaching Geography issues at Primary school Interdisciplinary approach of the Environmental Education . In June 2000, I gave two lectures in Kansas State University, Kansas, and Newmann University, Kansas State, USA. -

Macedonians and the Greek Civil War

Macedonians and the Greek Civil War By By Naum Peiov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) Macedonians and the Greek Civil War Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada Originally published in Macedonian in June 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2015 by Naum Peiov & Risto Stefov e-book edition November 16, 2015 2 INDEX Foreword ............................................................................................4 PART ONE – The Greek Civil War 1945 – 1949 - Introduction ......8 CHAPTER ONE – Unilateral Civil War .........................................21 CHAPTER TWO - Restoration of the monarchy ............................52 CHAPTER THREE – ESTABLISHING A DEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENT..............................................................................72 CHAPTER FOUR - Withdrawal of the Democratic Army .............81 PART TWO - Macedonians in the Greek Civil War .......................91 CHAPTER FIVE – Systematic persecution of the Macedonian people ...............................................................................................91 CHAPTER SIX - RESISTANCE TO NEW PRESSURE .............127 CHAPTER SEVEN - RELATIONS BETWEEN NOF AND THE CPG................................................................................................136 -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period.