Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Press Kit With

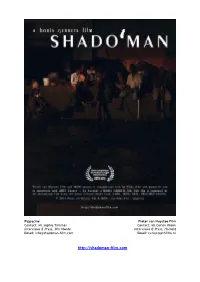

Pippaciné Pieter van Huystee Film Contact: Ms.Sophia Talamas Contact: Ms.Curien Kroon Interviews & Press, Worldwide Interviews & Press, Holland Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] http://shadoman-film.com SHADO’MAN Shot in Freetown, Sierra Leone 87 min, feature length documentary Available on DCP Original language Krio Subtitles English, French or Dutch LOGLINE A community of friends, each facing severe physical and psychological challenges, survives on the nocturnal streets of Freetown, Sierra Leone. The film delves deep into their life, telling a story of humanity and dignity in a world that otherwise offers little consolation. SYNOPSIS A bitter logic lies in the fact that those whom the society does not care to see are living by night. At the junction of Lightfoot-Boston and Wilberforce in downtown Freetown, Sierra Leone the streets of the city are covered in darkness. Only a few street lamps and flares of light from passing cars and motorcycles sporadically illuminate the Dantesque scenery. This is where a group of friends live. They call themselves the Freetown Streetboys, even though some women are among them. They each face enormous physical and psychological challenges. From early childhood when they endured the neglect and scorn of their parents until the present day, their life has been one of social abandonment by the world around them. With no place but the bleak and sleepless streets of the capital city, they are condemned to a life of begging. Shado’man is a cinematic journey undertaken by the filmmaker together with the ‘Streetboys’: Suley, Lama, David, Alfred, Shero and Sarah. -

Download the Monthly Film & Event Calendar

THU SAT WED 1:30 Film 1 10 21 3:10 to Yuma. T2 Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 1:30 Film 10:20 Family Film FRI Gallery Sessions The Armory Party 2018 Beloved Enemy. T2 Tours for Fours. Irresistible Forces, Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Wed, Mar 7, 9:00 p.m.–12:30 a.m. Education & Immovable 30 5:30 Film Museum galleries VIP Access at 8:00 p.m. Research Building Objects: The Films Film Janitzio. T2 of Amir Naderi. New Directors/ Join us for conversations and Celebrate the opening of The 10:20 Family 7:00 Film See moma.org/film New Films 2018. activities that offer insightful and Armory Show and Armory Arts A Closer Look for El Mar La Mar. T1 4:30 Film 1:30 Film 6:05 Event for details. See newdirectors.org unusual ways to engage with art. Week with The Armory Party SUN WED Kids. Education & FRI SAT MON Pueblerina. T2 Music by Luciano VW Sunday Sessions: for details. at MoMA—a benefit event with 7:30 Film Research Building 1:30 Film Limited to 25 participants 4 7 16 Berio and Bruno Hair Wars. MoMA PS1 24 26 live music and DJs, featuring María Calendaria. T2 7:30 Film Kings Go Forth. T2 10:20 Family 7:30 Event 2:00 Film Film Maderna. T1 Film Film platinum-selling artist BØRNS. Flor silvestre. T1 6:30 Film Art Lab: Nature Tours for Fours. Quiet Mornings. Victims of Sin. T2 Irresistible Forces, 4:30 Film Irresistible Forces, Irresistible Forces, 6:30 Film Music by Pink Floyd, Daily. -

Johan Van Der Keuken

HIVER 2018 RÉTROSPECTIVE JOHAN VAN DER KEUKEN DU COURT, TOUJOURS NOUVELLES ÉCRITURES DOCUMENTAIRES 1 2 ÉDITO À partir de janvier 2018, la Bibliothèque Organisée en trois grandes saisons publique d’information s’engage dans proposant chacune un cycle phare, un pari un peu fou : proposer chaque la programmation de la Bpi aura jour, aux curieux, aux cinéphiles, à tous, pour objectifs d’accompagner et de venir voir des films documentaires diffuser la création contemporaine, dans les salles du Centre Pompidou. de montrer les films de patrimoine Des films venus du monde entier, sur leur support d’origine et en version des grands classiques aux dernières restaurée, de valoriser et interroger créations, des films pour se donner le des corpus artistiques et thématiques, temps de regarder et penser le monde, à commencer au 1er trimestre 2018 ensemble, au cinéma. par une rétrospective consacrée au cinéaste néerlandais Johan van C’est toute l‘ambition de l’incarnation der Keuken. La cinémathèque du parisienne d’un projet à part, La documentaire à la Bpi proposera cinémathèque du documentaire. aussi des rendez-vous réguliers : courts métrages, nouvelles écritures, En résonance avec la société, ses travaux en cours, fenêtre sur festivals, espoirs, ses rêves, ses inquiétudes, avant-premières…, ainsi qu’un volet la création documentaire connaît d’éducation à l’image destiné aux une effervescence extraordinaire. scolaires. Elle attire un public toujours plus nombreux. Au cinéma, à la télévision, Le cinéma documentaire a toujours sur les réseaux numériques, elle été au cœur de l’identité de la Bpi qui enrichit chaque jour un fonds d’une fut en 1977 la première bibliothèque exceptionnelle diversité de regards, multimédia en France. -

Bamcinématek Presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 Tales of Rampaging Beasts and Supernatural Terror

BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, Oct 26—Nov 1 Highlighting 10 tales of rampaging beasts and supernatural terror September 21, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, October 26 through Thursday, November 1 BAMcinématek presents Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror, a series of 10 films showcasing two strands of Japanese horror films that developed after World War II: kaiju monster movies and beautifully stylized ghost stories from Japanese folklore. The series includes three classic kaiju films by director Ishirô Honda, beginning with the granddaddy of all nuclear warfare anxiety films, the original Godzilla (1954—Oct 26). The kaiju creature features continue with Mothra (1961—Oct 27), a psychedelic tale of a gigantic prehistoric and long dormant moth larvae that is inadvertently awakened by island explorers seeking to exploit the irradiated island’s resources and native population. Destroy All Monsters (1968—Nov 1) is the all-star edition of kaiju films, bringing together Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and King Ghidorah, as the giants stomp across the globe ending with an epic battle at Mt. Fuji. Also featured in Ghosts and Monsters is Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (1968—Oct 27), an apocalyptic blend of sci-fi grotesquerie and Vietnam-era social commentary in which one disaster after another befalls the film’s characters. First, they survive a plane crash only to then be attacked by blob-like alien creatures that leave the survivors thirsty for blood. In Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku (1960—Oct 28) a man is sent to the bowels of hell after fleeing the scene of a hit-and-run that kills a yakuza. -

De Grote Vakantie / Die Großen Ferien

7 DE GROTE VAKANTIE Die Großen Ferien The Long Holiday Regie: Johan van der Keuken Land: Niederlande 1999. Produktion: Pietervan Huystee Film & Synopsis TV. Regie, Kamera: )ohan van der Keuken. Ton: Noshka van der In October 1998, Johan van der Keuken called his doc - Lely. Schnitt: Menno Boerema. tor (the head of radiotherapy) at the Academic Hospital Format: 35mm, 1:1.66, Farbe. Länge: 145 Minuten, 25 Bilder/Sek. in Utrecht from Paris and heard that he only had a few- Uraufführung: Januar 2000, Filmfestival Rotterdam. years to live. Prostate cancer cells had taken hold in his Sprachen: Niederländisch, tibetanis< h, englisch, französisi h. son- body. ray, moree. Van der Keuken has travelled the world for years with Ins Drehorte: Nepal, Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Brasilien, USA und wife Nosh van der Lely. She held the microphone and die Niederlande. recorder, he wielded the camera. Together they decided Weltvertrieb: Ideale Audience Distribution (Susanna Scott), 13 to spend the rest of their precious time looking and lis• rue Portefoin, 75003 Paris, Frankreich. Tel.: (33-1) 42 77 89 70. tening. At Christmas they set off for Bhutan. Johan van Fax: (33-1) 42 77 36 56. E-mail: [email protected] der Keuken regarded the film they were embarking on as a chronicle of his own view of the world, made all the Inhalt more urgent by his own mortality. Later in the film - and Im Oktober 1998 rief Johan van der Keuken seinen Arzt (den in his life - things take a turn for the better, when Johan ( hefarzt der Abteilung Strahlentherapie) an der Universitätsklinik finds a new medicine in the United States that drastically in Utrecht von Paris aus an und erfuhr, daß er nur noch einige increases his chanc es of sur\ iv al. -

L'œuvre De Johan Van Der Keuken Et Son Contexte : Contre Le Documentaire, Tout Contre

L'œuvre de Johan van der Keuken et son contexte : contre le documentaire, tout contre. Par Robin Dereux La position de Johan van der Keuken par rapport au genre documentaire ne peut pas se résumer en une phrase. Elle est complexe, variable selon les époques, et lui-même donne régulièrement l’impression d’entretenir une certaine ambiguïté par rapport à cette question. D’autre part, on sent bien que ce qu’il expose dans les entretiens avec la presse repose largement sur des malentendus et sur l’attente de son interlocuteur. Les historiens y verront peut-être une attitude paradoxale: van der Keuken critique souvent le genre mais inscrit aussi ses films dans des “festivals documentaires”. S’il cite souvent en référence des cinéastes emblématiques (Leacock par exemple), et d’autres qui ont pu, à un moment ou à un autre, être assimilés au “documentaire”, bien que leur travail transcende les genres (comme Ivens ou Rouch), il se réfère au moins autant à des cinéastes de fiction (Hitchcock, Resnais), et parfois également à des cinéastes expérimentaux (Jonas Mekas, Yervant Gianikian et Angela Ricci Luchi). Tout est donc question de point de vue, et van der Keuken donne souvent l’impression, dans ses textes et entretiens, de ménager les différentes interprétations. Son attitude, à la fois volontaire et douce, l’amène parfois au sentiment d’être incompris, quand la distance est trop grande entre sa recherche et les questions qui lui sont posées. Il ne lui reste alors plus qu’à répéter toujours la même phrase: “on ne peut pas se contenter d’une description primaire du réel”, que l’on peut interpréter comme une mise en garde contre l’assimilation trop rapide à un genre avec lequel il se débat. -

The Choice of Topics in Male, Female and Mixed-Sex Groups of Students

DOI: 10.9744/kata.19.2.63-70 ISSN 1411-2639 (Print), ISSN 2302-6294 (Online) OPEN ACCESS http://kata.petra.ac.id Transposition of the Scientific Elements in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Adaptation of Kobo Abe’s the Face of Another Anton Sutandio Maranatha Christian University, INDONESIA e-mails: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article focuses on Hiroshi Teshigahara‟s film adaptation of the famous Kobo Abe‟s The Face of Another with special attention on the transposition of the scientific elements of the novel in the film. This article observes how Teshigahara, through cinematic techniques, transposes Abe‟s scientific language into visual forms. Abe himself involved in the film adaptation by writing the screenplay, in which he prioritized the literary aspects over the filmic aspect. This makes the adaptation become more interesting because Teshigahara is known as a stylish filmmaker. Another noteworthy aspect is the internal dialogues domination within the novel narration. It is written in an epistolary-like narration, placing the protagonist as a single narrator which consequently raises subjectivity. The way Teshigahara externalizes the stream-of-consciousness narration-like into the medium of film is another significant topic of this essay. Keywords: Transposition, scientific element, adaptation, The Face of Another. INTRODUCTION alienation and isolation. It tells a story about a man named Okuyama, a scientist, whose face is deformed This research aims to investigate the way Hiroshi due to a freak laboratory incident. He experiences Teshigahara transposes the novel of Kobo Abe, The stress and trauma and decides to consult a doctor Face of Another, into a film with special attention on named K and discuss the possibility of creating a the transposition of the scientific elements of the mask, or a face for him. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 "Our Subcultural Shit-Music": Dutch Jazz, Representation, and Cultural Politics ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op dinsdag 17 mei 2016, te 14.00 uur door Loes Rusch geboren te Gorinchem Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. -

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations

Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Proefschrift voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de kunsten: audiovisuele kunsten Figures of Dissent Cinema of Politics / Politics of Cinema Selected Correspondences and Conversations Stoffel Debuysere Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Doctor of Arts: Audiovisual Arts Academic year 2017- 2018 Doctorandus: Stoffel Debuysere Promotors: Prof. Dr. Steven Jacobs, Ghent University, Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Dr. An van. Dienderen, University College Ghent School of Arts Editor: Rebecca Jane Arthur Layout: Gunther Fobe Cover design: Gitte Callaert Cover image: Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep (1977). Courtesy of Charles Burnett and Milestone Films. This manuscript partly came about in the framework of the research project Figures of Dissent (KASK / University College Ghent School of Arts, 2012-2016). Research financed by the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent. This publication would not have been the same without the support and generosity of Evan Calder Williams, Barry Esson, Mohanad Yaqubi, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Sarah Vanhee, Christina Stuhlberger, Rebecca Jane Arthur, Herman Asselberghs, Steven Jacobs, Pieter Van Bogaert, An van. Dienderen, Daniel Biltereyst, Katrien Vuylsteke Vanfleteren, Gunther Fobe, Aurelie Daems, Pieter-Paul Mortier, Marie Logie, Andrea Cinel, Celine Brouwez, Xavier Garcia-Bardon, Elias Grootaers, Gerard-Jan Claes, Sabzian, Britt Hatzius, Johan Debuysere, Christa -

Johan Van Der Keuken's Global Amsterdam

7. Form, Punch, Caress: Johan van der Keuken’s Global Amsterdam Patricia Pisters After many years of travelling the world with his camera, in the early 1990s doc- umentary filmmaker Johan van der Keuken expressed his surprise at the many changes that had taken place in his hometown of Amsterdam: ‘To tell the truth, I didn’t recognize all the cultures that had settled there in the past few decades, nor the subcultures and “gangs” that had sprung up’. At the same time, he realized that ‘my city, Amsterdam, was the place where everything that I could see eve- rywhere else was represented’, and that in order to understand the world, all he needed to do was direct his camera to his own neighbourhood (van der Keuken, qtd. in Albera 2006, 16). This is when he decided to make Amsterdam Global Village, a four-hour documentary filmed in Amsterdam in the mid-1990s. He made it in his characteristic fashion, travelling through the city with his camera, visiting some of its inhabitants in their homes, listening to their stories, and some- times following them to places elsewhere in the world – but always to return. Johan van der Keuken captured Amsterdam with his camera from the very start of his career, following his studies at the Institut des Hautes Études Ciné- matographiques (IDHEC) in Paris in the late 1950s. As he regularly applied his camera to Amsterdam through several decades, his work forms a rich – and very personal – archive of historical impressions of an ever-changing city. Looking at some key films situated in Amsterdam, such as Beppie (1965), Four Walls (1965), Iconoclasm – A Storm of Images (1982), and Amsterdam Global Village (1996), this essay presents a double portrait of the Amsterdam corpus within van der Keuken’s oeuvre. -

Transposition of the Scientific Elements in Hiroshi Teshigahara's

DOI: 10.9744/kata.19.2.63-70 ISSN 1411-2639 (Print), ISSN 2302-6294 (Online) OPEN ACCESS http://kata.petra.ac.id Transposition of the Scientific Elements in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Adaptation of Kobo Abe’s the Face of Another Anton Sutandio Maranatha Christian University, INDONESIA e-mails: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article focuses on Hiroshi Teshigahara‟s film adaptation of the famous Kobo Abe‟s The Face of Another with special attention on the transposition of the scientific elements of the novel in the film. This article observes how Teshigahara, through cinematic techniques, transposes Abe‟s scientific language into visual forms. Abe himself involved in the film adaptation by writing the screenplay, in which he prioritized the literary aspects over the filmic aspect. This makes the adaptation become more interesting because Teshigahara is known as a stylish filmmaker. Another noteworthy aspect is the internal dialogues domination within the novel narration. It is written in an epistolary-like narration, placing the protagonist as a single narrator which consequently raises subjectivity. The way Teshigahara externalizes the stream-of-consciousness narration-like into the medium of film is another significant topic of this essay. Keywords: Transposition, scientific element, adaptation, The Face of Another. INTRODUCTION alienation and isolation. It tells a story about a man named Okuyama, a scientist, whose face is deformed This research aims to investigate the way Hiroshi due to a freak laboratory incident. He experiences Teshigahara transposes the novel of Kobo Abe, The stress and trauma and decides to consult a doctor Face of Another, into a film with special attention on named K and discuss the possibility of creating a the transposition of the scientific elements of the mask, or a face for him. -

Virtuose Et Moderne · Photo Bernard Prim LE GENOU DE CLAIRE

janvier - février 2018 · NOS PHOTOS DE TOURNAGE · ANNE-MARIE MIÉVILLE · PROJECTIONS FAMILLE · FILMS NOIRS, FILMS D’ANGOISSE · COMBIEN D’ENTRE NOUS ? : LES FILMS DE GHASSAN SALHAB 18 janvier — 5 février virtuose et moderne Photo Bernard Prim · LE GENOU DE CLAIRE CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA RENSEIGNEMENTS HEURES D’OUVERTURE INFO-PROGRAMMATION : CINEMATHEQUE.QC.CA ou 514.842.9763 BILLETTERIE : DROITS D’ENTRÉE1 : ADULTES 10 $ LUNDI À VENDREDI DÈS 10 h 4-16 ANS, ÉTUDIANTS ET AÎNÉS 9 $2 · 1-3 ANS GRATUIT SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DÈS 14 h FAMILLE 3 PERSONNES 20 $ · FAMILLE 4 PERSONNES 25 $ EXPOSITIONS : MEMBRE ET ABONNEMENT RÉGULIER3 : 1 PERSONNE 120 $ / 1 AN LUNDI À VENDREDI DE MIDI À 21 h ABONNEMENT ÉTUDIANT3 : 1 PERSONNE 99 $ / 1 AN SAMEDI ET DIMANCHE DE 14 h À 21 h PROGRAMMATION ART ET ESSAI : MÉDIATHÈQUE GUY-L.-COTÉ : 12 $ / TARIF RÉGULIER · 9 $ / TARIF AINÉS, ÉTUDIANTS, MEMBRES ET ABONNÉS MARDI À VENDREDI DE 9 h 30 À 17 h EXPOSITIONS : ENTRÉE LIBRE BAR SALON : 1. Taxes incluses. Le droit d’entrée peut différer dans le cas de certains programmes spéciaux. LUNDI DE 10 h 15 À 18 h 2. Sur présentation d’une carte d’étudiant ou d’identité. 3. Accès illimité à la programmation régulière. MARDI À VENDREDI DE 10 h 15 À 22 h CINÉMATHÈQUE QUÉBÉCOISE : 335, boul. de Maisonneuve Est, Montréal (Québec) Canada H2X 1K1 · Métro Berri-UQAM Distribué par Publicité sauvage DESIGN AGENCE CODE Imprimé au Québec sur papier québécois recyclé à 100 % (post-consommation) MA NUIT CHEZ MAUD Rohmer, virtuose et moderne Photo Bernard Prim LE GENOU DE CLAIRE ·: DU 18 JANVIER AU 5 FÉVRIER :· Au début des années 1960, le futur cinéaste Barbet Schroeder a créé pour Eric Rohmer la société de production des Films du Losange, tou- jours active aujourd’hui, accompagnatrice de nombreux cinéastes mar- quants, dont Michael Haneke.