Iron Age Chronology in the Carpathian Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL TRANS/WP.5/2005/16/Add.8 24 October 2005 ENGLISH ONLY ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE INLAND TRANSPORT COMMITTEE Working Party on Transport Trends and Economics (Eighteenth session, 15-16 September 2005, agenda item 3(b)) MONITORING OF DEVELOPMENTS RELEVANT FOR THE PAN-EUROPEAN TRANSPORT CORRIDORS AND AREAS Infrastructure bottlenecks and missing links Transmitted by the Government of Hungary According to the report on “Infrastructure Bottlenecks and Missing Links in the European Transport Network” bottlenecks can be caused by: (1) insufficient infrastructure capacity; (2) low quality of transport infrastructure. In the same manner, the phenomenon of a “missing link” may be considered as a situation in which the quality of service has extremely low values due to the fact that no direct link exists between two points. As described in the above-mentioned document, as a simplified method, for individual road categories, one may take the following capacities in terms of number of vehicles as the average daily traffic: − 4-lane motorway: 40,000 – 60,000 PCU/24 hrs − roads of 2 lanes: 8,000 – 12,000 PCU/24 hrs As in the case of roads, there are a great number of factors determining the bottlenecks on a railway line. It is practically impossible to concentrate all elements in a single bottleneck measure. In order to reach practical measures it appeared appropriate to take the following capacity limits: TRANS/WP.5/2005/16/Add.8 page 2 − Single track main lines: 1 x 60 – 80 trains/day − Double track main lines: 2 x 100 – 200 trains/day According to that definition, the bottlenecks regarding the Hungarian TEN road network are described below. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1939 Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum Joseph Robert Koch Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Koch, Joseph Robert, "Quintilian and the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum" (1939). Master's Theses. 471. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/471 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1939 Joseph Robert Koch ~' ------------------------------------------------. QUINTILIAN AND THE JESUIT RATIO STUDIORUM J by ., Joseph Robert Koch, S.J. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University. 1939 21- TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I Introduction 1 Chapter II Quintilian's Influence on 11 the Renaissance Educators Chapter III Quintilian's Ideal Orator 19 and the Jesuit Eloquentia Perfecta J " Chapter IV The Prelection 28 Chapter V Composition and Imitation 40 Chapter VI Enru.lation 57 Chapter VII Conclusion 69 A' ~J VITA AUCTORIS Joseph Robert Koch, S.J. was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, April 13, 1913. After receiving his elementary education at the Ursuline Academy he entered St. Xavier' High School, CinCinnati, in September, 1926. He grad uated from St. Xavier in June, 1930 and entered the Society of Jesus at Milford, Ohio, in August of th' " same year. -

What an Almost 500-Year-Old Map Can Tell to a Geoscientist

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Acta Geod. Geoph. Hung., Vol. 44(1), pp. 3–16 (2009) DOI: 10.1556/AGeod.44.2009.1.2 REDISCOVERING THE OLD TREASURES OF CARTOGRAPHY — WHAT AN ALMOST 500-YEAR-OLD MAP CAN TELL TO A GEOSCIENTIST BSzekely´ 1,2 1Christian Doppler Laboratory, Institute of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, Vienna University of Technology, Gusshausstr. 27–29, A-1040 Vienna, Austria, e-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Geophysics and Space Science, Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, E¨otv¨os University, P´azm´any P. s´et´any 1/C, H-1117 Budapest, Hungary Open Access of this paper is sponsored by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund under the grant No. T47104 OTKA (for online version of this paper see www.akkrt.hu/journals/ageod) Tabula Hungariae (1528), created by Lazarus (Secretarius), is an almost 500 year-old map depicting the whole Pannonian Basin. It has been used for several geographic and regional science studies because of its highly valued information con- text. From geoscientific point of view this information can also be evaluated. In this contribution an attempt is made to analyse in some extent the paleo-hydrogeography presented in the map, reconsidering the approach of previous authors, assuming that the mapmaker did not make large, intolerable errors and the known problems of the cartographic implementation are rather exceptional. According to the map the major lakes had larger extents in the 16th century than today, even a large lake (Lake Becskerek) ceased to exist. -

Act Cciii of 2011 on the Elections of Members Of

Strasbourg, 15 March 2012 CDL-REF(2012)003 Opinion No. 662 / 2012 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ACT CCIII OF 2011 ON THE ELECTIONS OF MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT OF HUNGARY This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2012)003 - 2 - The Parliament - relying on Hungary’s legislative traditions based on popular representation; - guaranteeing that in Hungary the source of public power shall be the people, which shall pri- marily exercise its power through its elected representatives in elections which shall ensure the free expression of the will of voters; - ensuring the right of voters to universal and equal suffrage as well as to direct and secret bal- lot; - considering that political parties shall contribute to creating and expressing the will of the peo- ple; - recognising that the nationalities living in Hungary shall be constituent parts of the State and shall have the right ensured by the Fundamental Law to take part in the work of Parliament; - guaranteeing furthermore that Hungarian citizens living beyond the borders of Hungary shall be a part of the political community; in order to enforce the Fundamental Law, pursuant to Article XXIII, Subsections (1), (4) and (6), and to Article 2, Subsections (1) and (2) of the Fundamental Law, hereby passes the following Act on the substantive rules for the elections of Hungary’s Members of Parliament: 1. Interpretive provisions Section 1 For the purposes of this Act: Residence: the residence defined by the Act on the Registration of the Personal Data and Resi- dence of Citizens; in the case of citizens without residence, their current addresses. -

Hungary's National Energy Efficiency Action Plan Until 2020

Hungary’s National Energy Efficiency Action Plan until 2020 Mandatory reporting under Article 24(2) of Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on energy efficiency August 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................................... 5 1.1 Hungary’s economic situation, influencing factors ..................................................... 6 1.2. Energy policy ............................................................................................................... 9 2. OVERVIEW OF NATIONAL ENERGY EFFICIENCY TARGETS AND SAVINGS 14 2.1 Indicative national 2020 energy efficiency target ..................................................... 14 2.2 Method of calculation ................................................................................................ 15 2.3 Overall primary energy consumption in 2020 and values by specific industries ...... 18 2.4 Final energy savings .................................................................................................. 19 3. POLICY MEASURES IMPLEMENTING EED ............................................................. 21 3.1 Horizontal measures .................................................................................................. 21 3.1.1 -

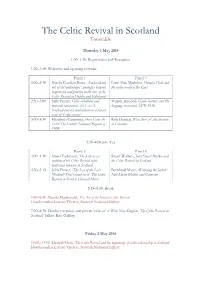

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable

The Celtic Revival in Scotland Timetable Thursday 1 May 2014 1:00–1:30: Registration and Reception 1:30–1:50: Welcome and opening remarks Panel 1 Panel 2 2:00–2:30 Nicola Gordon Bowe, ‘Embroideries Liam Mac Mathúna, Douglas Hyde and out of old mythologies’: analogies between the wider world of the Gael inspiration and practice in the arts of the Celtic Revival in Dublin and Edinburgh 2:30–3:00 Sally Foster, Celtic collections and Wilson McLeod, Gaelic learners and the imperial connections: the V&A, language movement, 1870-1930 Scotland and the multiplication of plaster casts of ‘Celtic crosses’ 3:00–3:30 Elizabeth Cumming, Here Come the Rob Dunbar, Was there a Celtic Revival Celts! The Scottish National Pageant of in Canada? 1908 3:30–4:00 pm: Tea Panel 3 Panel 4 4:00–4:30 Stuart Eydmann, The harp as an Stuart Wallace, John Stuart Blackie and emblem of the Celtic Revival, with the Celtic Revival in Scotland particular reference to Scotland 4:30–5.15 John Purser, ‘The Lay of the Last Bernhard Maier, ‘Widening the Jacket’: Minstrel? Don’t count on it’: The Celtic John Stuart Blackie and Germany Revival in Scottish Classical Music 5:15–5:30: Break 5:30–6:30: Murdo Macdonald, The Art of the Scottish Celtic Revival Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish National Gallery 7:00–8:30: Drinks reception and private view of A Wide New Kingdom: The Celtic Revival in Scotland, Talbot Rice Gallery. Friday 2 May 2014 10:00–11:00: Donald Meek, The Celtic Revival and the beginnings of Celtic scholarship in Scotland Hawthornden Lecture Theatre, Scottish -

S. Transdanubia Action Plan, by Pécs-Baranya, HU

Cultural and Creative Industries (CCIs) contribution to Cultural and Creative Tourism (CCT) in Europe Action Plan for South Transdanubia, Hungary ChamMap of partnerber of are Commercea / Partner info and Industry of Pécs- Baranya May 2021 Cultural and Creative Industries contribution to Cultural and Creative Tourism in Europe _________________________ © Cult-CreaTE Project Partnership and Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Pécs-Baranya, Hungary This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Cult-CreaTE Project Management and Coordination Unit and the respective partner: Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Pécs-Baranya Citation: Interreg Europe Project Cult-CreaTE Action Plan Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Pécs- Baranya, Hungary The Cult-CreaTE Project Communications unit would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this action plan as a source, sent to e-mail: [email protected] Disclaimer This document has been prepared with the financial support of Interreg Europe 2014-2020 interregional cooperation programme. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Pécs-Baranya and in no way reflect the views of the Cult-CreaTE partnership, the European Union institutions, nor the Managing Authority of the Programme. Any reliance or action taken based on the information, materials and techniques described within this document are the responsibility of the user. -

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins Coins were developed about 650 BC on the western coast of modern Turkey. From there, they quickly spread to the east and the west, and toward the end of the 5th century BC coins reached the Celtic tribes living in central Europe. Initially these tribes did not have much use for the new medium of exchange. They lived self-sufficient and produced everything needed for living themselves. The few things not producible on their homesteads were bartered with itinerant traders. The employ of money, especially of small change, is related to urban culture, where most of the inhabitants earn their living through trade or services. Only people not cultivating their own crop, grapes or flax, but buying bread at the bakery, wine at the tavern and garments at the dressmaker do need money. Because by means of money, work can directly be converted into goods or services. The Celts in central Europe presumably began using money in the course of the 4th century BC, and sometime during the 3rd century BC they started to mint their own coins. In the beginning the Celtic coins were mere imitations of Greek, later also of Roman coins. Soon, however, the Celts started to redesign the original motifs. The initial images were stylized and ornamentalized to such an extent, that the original coins are often hardly recognizable. 1 von 16 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. -

Belgyógyászat 0102

Járó-TEK 2014-09-24 Szolgáltató adatlap - Összes szakma Általános adatok: Szolgáltató kódja : 103500 Szolgáltató megnevezése : Albert Schweitzer Kórház-Rendel őintézet Szolgáltató címe : 3000 Hatvan Balassi Bálint út 16 Telefon : 06-37/341-033 Telephelyei 2170 Aszód Baross u. 4. 2170 Aszód Kossuth L. u. 78. 0100 : belgyógyászat általános belgyógyászat – ellátás Címe: 3000 Hatvan Balassi Bálint út 16 2170 Aszód Baross u. 4. Zagyvaszántó, Rózsaszentmárton, Pet őfibánya, Nagykökényes, Lőrinci, Kerekharaszt, Hort, Heréd, Hatvan, Ecséd, Csány. Boldog, Apc Iklad, Domony, Váckisújfalu, Bag, Tura, Hévízgyörk, Aszód, Galgahévíz, Verseg, Galgamácsa, Vácegres, Kartal Kúraszer ű ellátás - belgyógyászat Címe: 3000 Hatvan Balassi Bálint út 16 Zagyvaszántó, Rózsaszentmárton, Pet őfibánya, Nagykökényes, Lőrinci, Kerekharaszt, Hort, Heréd, Hatvan, Ecséd, Csány. Boldog, Apc Iklad, Domony, Váckisújfalu, Bag, Tura, Hévízgyörk, Aszód, Galgahévíz, Verseg, Galgamácsa, Vácegres, Kartal 0102 : haematológia haematológia – ellátás Címe: 3000 Hatvan Balassi Bálint út 16 Zagyvaszántó, Rózsaszentmárton, Pet őfibánya, Nagykökényes, Lőrinci, Kerekharaszt, Hort, Heréd, Hatvan, Ecséd, Csány. Boldog, Apc Iklad, Domony, Váckisújfalu, Bag, Tura, Hévízgyörk, Aszód, Galgahévíz, Verseg, Galgamácsa, Vácegres, Kartal 1 0103 : endokrinológia, anyagcsere és diabetológia endokrinológia, anyagcsere és diabetológia – ellátás Címe: 3000 Hatvan Balassi Bálint út 16 Zagyvaszántó, Rózsaszentmárton, Pet őfibánya, Nagykökényes, Lőrinci, Kerekharaszt, Hort, Heréd, Hatvan, Ecséd, Csány. Boldog, -

BTC EGTC, Region's Bridge of Innovation

BTC EGTC, 20 region’s bridge 18 of innovation Preface City mayors from three countries collaboration. This is particularly have created the idea of the important for us, since we want to Grouping in 2009. keep economical, commercial, social The Grouping was established in contacts in the region covered by order to achieve their main goal BTC EGTC group. - the reducing of development The Grouping’s primary goal is a diff erences in the area surrounding harmonical regional development, the Hungarian-Romanian-Serbian improvement of the economical, border. social and territorial cohesion, as The establishment of BTC EGTC well as enabling a successful cross- provides such opportunities, which border collaboration. help to remove the borders in the region, and build bridges between BTC EGTC the local authorities, in their organization 2 BTC EGTC Introduction On 17th June 2009, almost fi fty mayors from the triple-border region municipalities decided to establish a European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC) named „Banat - Triplex Confi nium” in a summit in Mórahalom. The headquarters of the Group is also in Mórahalom. The initial membership of BTC EGTC contained 37 Hungarian municipalities, 37 Romanian municipalities, as well as 8 Serbian towns as observing members. Another three Hungarian municipalities joined the Group in 2012 - Csengele, Kistelek and Zá- kányszék. Banat-Triplex Confi nium EGTC members are the following: BTC EGTC, region’s bridge of innovation 2018 Hungary • Ambrózfalva • Ferencszállás • Kunbaja • Öttömös • Apátfalva -

Are Motorways Good for the Hungarian Economy?

Are motorways good for the Hungarian economy? by András Lukács Clean Air Action Group, Hungary www.levego.hu Budapest, 2003 Are motorways good for the Hungarian economy? by András Lukács (Clean Air Action Group) „...what does the EU give to Hungary, and what do we spend the money on? I agree with those who say that at most 30 per cent of the received funds should be spent on boosting the economy, and 70 per cent should be invested into the Hungarian society itself. The newly admitted countries invested a substantial part of the money from the Structural and Cohesion Funds into their infrastructure, the only exception being Ireland. They spent 80 per cent of the EU support on education, on building a knowledge-based society. Look at them now, how far the Irish have reached!” István Fodor, President of Ericsson Hungary, and Chairman of the Hungarian EU Enlargement Business Council („Üzleti 7”, 16th December 2002) Hungarian Governments of the recent years, one after the other, tried to outdo their predecessors by planning to build even more motorways. On this issue there is a consensus among all the political parties of the Hungarian Parliament. At the same time more and more people question the rationality of these investments, but such opinions hardly gain any publicity. Will motorways improve accessibility? One of the main reasons usually brought forward to support the construction of motorways is that they will improve accessibility to the region concerned. Of course, if we only compare the time that cars, buses or trucks spend on the motorway with the time of travelling on parallel roads, this statement holds true in general.