Cultural Identity Across Three Generations of an Anglo-Dakota Family

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native American Context Statement and Reconnaissance Level Survey Supplement

NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for The City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning & Economic Development Prepared by Two Pines Resource Group, LLC FINAL July 2016 Cover Image Indian Tepees on the Site of Bridge Square with the John H. Stevens House, 1852 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 583) Minneapolis Pow Wow, 1951 Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Neg. No. 35609) Minneapolis American Indian Center 1530 E Franklin Avenue NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT Prepared for City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development 250 South 4th Street Room 300, Public Service Center Minneapolis, MN 55415 Prepared by Eva B. Terrell, M.A. and Michelle M. Terrell, Ph.D., RPA Two Pines Resource Group, LLC 17711 260th Street Shafer, MN 55074 FINAL July 2016 MINNEAPOLIS NATIVE AMERICAN CONTEXT STATEMENT AND RECONNAISSANCE LEVEL SURVEY SUPPLEMENT This project is funded by the City of Minneapolis and with Federal funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. -

Little Crow Historic Canoe Route

Taoyateduta Minnesota River HISTORIC water trail BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA Twin Valley Council U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 AUGUST 17, 1862 The TA-OYA-TE DUTA Fish and Wildlife Minnesota River Historic Water Four Dakota men kill five settlers The Minnesota River Basin is a Trail, is an 88 mile water route at Acton in Meeker County birding paradise. The Minnesota stretching from just south of AUGUST 18 River is a haven for bird life and Granite Falls to New Ulm, Minne- several species of waterfowl and War begins with attack on the sota. The river route is named af- riparian birds use the river corri- Lower Sioux Agency and other set- ter Taoyateduta (Little Crow), the dor for nesting, breeding, and rest- tlements; ambush and battle at most prominent Dakota figure in ing during migration. More than the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Redwood Ferry. Traders stores 320 species have been recorded in near Upper Sioux Agency attacked the Minnesota River Valley. - The Minnesota River - AUGUST 19 Beneath the often grayish and First attack on New Ulm leading to The name Minnesota is a Da- cloudy waters of the Minnesota its evacuation; Sibley appointed kota word translated variously as River, swim a diverse fish popula- "sky-tinted water” or “cloudy-sky tion. The number of fish species commander of U.S. troops water". The river is gentle and and abundance has seen a signifi- AUGUST 20 placid for most of its course and cant rebound over the last several First Fort Ridgely attack. one will encounter only a few mi- years. -

North Dakota Social Studies Content Standards Grades K-12 August 2019

North Dakota Social Studies Content Standards Grades K-12 August 2019 North Dakota Department of Public Instruction Kirsten Baesler, State Superintendent 600 East Boulevard Avenue, Dept. 201 Bismarck, North Dakota 58505-0440 www.nd.gov/dpi North Dakota Social Studies Writing Team RaeAnne Axtman Kari Hall Brett Mayer Schmit Cheney Middle School, West Fargo Williston High School, Williston Sheyenne High School, West Fargo Brenda Beck Clay Johnson Laura Schons Larimore Public School, Larimore North Border School District, Pembina Independence Elementary, West Fargo Nicole Beier Justin Johnson Rachel Schuehle South High School, Fargo Schroeder Middle School, Grand Forks St. Mary's Central High School, Bismarck Kimberly Bollinger Jennifer Kallenbach Matthew Slocomb Bennett Elementary School, Fargo Kidder County High School, Steele West Fargo High School, West Fargo Sarah Crossingham Shalon Kirkwood Joseph Stuart Wishek Public School, Wishek Liberty Middle School, West Fargo University of Mary, Bismarck Denise Dietz Candice Klipfel Karla Volrath Lincoln Elementary, Beach Ellendale High School, Ellendale Washington Elementary, Fargo Kaye Fischer David Locken Kathryn Warren West Fargo Public Schools, West Fargo Fessenden-Bowdon Public School, Fessenden Oakes Public School, Oakes Siobhan Greene Nicole Nicholes Nicholas Wright Mandaree Public School, Mandaree Erik Ramstad Middle School, Minot Oak Grove Lutheran School, Fargo North Dakota Social Studies Review Team Sharon Espeland, General Public Neil Howe, General Public Larry Volk, General Public -

Forty Years with the Sioux / by Stephen R. Riggs

MARY AND I. FORTY YEARS WITH THE Sioux. BY STEPHEN R. RIGGS, D.D., LL D., Missionary of the A. B. C. F. M; and Author of " Dakota Grammar and Dictionary," and " Gospel Among the Dakotas," etc. WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY REV. S. C. BARTLETT, D.D., President of Dartmouth College. CHICAGO: W. G. HOLMES, 77 MADISON STREET. Copyrighted, March, 1880. BY STEPHEN R. RIGOS. Blakely, Brown & Manh, Printer*, 155 and 157 Dearborn St. TO MY CHILDREN, ALFRED, ISABELLA, MARTHA, ANNA, THOMAS, HENRY, ROBERT, CORNELIA AND EDNA ; Together with all the GRANDCHILDREN Growing up into the MISSIONARY INHERITANCE OF THEIR FATHERS AND MOTHERS, This Book is inscribed, By the Author. PREFACE. PREFACE. This book I have INSCRIBED to my own family. be of interest to them, as, in part, a history of their father and mother, in the toils, and sacrifices, and rewards, of commencing and carrying forward the work of evangeliz- ing the Dakota people. Many others, who are interested in the uplifting of the Red Men, may be glad to obtain glimpses, in these pages, of the inside of Missionary Life in what was, not long since, the Far West; and to trace the threads of the inweaving of a Christ-life into the lives of many of the Sioux nation. "Why don't you tell more about yourselves?" is a question, which, in various forms, has been often asked me, during these last four decades. Partly as the answer to questions of that kind, this book assumes somewhat the form of a personal narrative. Years ago it was an open secret, that our good and noble friend, SECRETARY S. -

The Life and Times of Cloud Man a Dakota Leader Faces His Changing World

RAMSEY COUNTY All Under $11,000— The Growing Pains of Two ‘Queen Amies’ A Publication o f the Ramsey County Historical Society Page 25 Spring, 2001 Volume 36, Number 1 The Life and Times of Cloud Man A Dakota Leader Faces His Changing World George Catlin’s painting, titled “Sioux Village, Lake Calhoun, near Fort Snelling.” This is Cloud Man’s village in what is now south Minneapolis as it looked to the artist when he visited Lake Calhoun in the summer of 1836. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. See article beginning on page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 36, Number 1 Spring, 2001 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Howard M. Guthmann CONTENTS Chair James Russell 3 Letters President Marlene Marschall 4 A ‘Good Man’ in a Changing World First Vice President Cloud Man, the Dakota Leader, and His Life and Times Ronald J. Zweber Second Vice President Mark Dietrich Richard A. Wilhoit Secretary 25 Growing Up in St. Paul Peter K. Butler All for Under $11,000: ‘Add-ons,’ ‘Deductions’ Treasurer The Growing Pains of Two ‘Queen Annes’ W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Norbert Conze- Bob Garland mius, Anne Cowie, Charlotte H. Drake, Joanne A. Englund, Robert F. Garland, John M. Harens, Rod Hill, Judith Frost Lewis, John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Marlene Marschall, Richard T. Publication of Ramsey County History is supported in part by a gift from Murphy, Sr., Richard Nicholson, Linda Owen, Clara M. Claussen and Frieda H. Claussen in memory of Henry H. -

Marpiyawicasta Man of the Clouds, Or “L.O

MARPIYAWICASTA MAN OF THE CLOUDS, OR “L.O. SKYMAN” “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Man of the Clouds HDT WHAT? INDEX MAN OF THE CLOUDS MARPIYAWICASTA 1750 Harold Hickerson has established that during the 18th and early 19th Centuries, there was a contested zone between the Ojibwa of roughly Wisconsin and the Dakota of roughly Minnesota that varied in size from 15,000 square miles to 35, 000 square miles. In this contested zone, because natives entering the region to hunt were “in constant dread of being surprised by enemies,” game was able to flourish. At this point, however, in a war between the Ojibwa and the Dakota for control over the wild rice areas of northern Minnesota (roughly a quarter of the caloric intake of these two groups was coming from this fecund wild rice plant of the swampy meadows) , the Ojibwa decisively won. HDT WHAT? INDEX MARPIYAWICASTA MAN OF THE CLOUDS HDT WHAT? INDEX MAN OF THE CLOUDS MARPIYAWICASTA This would have the ecological impact of radically increasing human hunting pressure within that previously protected zone. I have observed that in the country between the nations which are at war with each other the greatest number of wild animals are to be found. The Kentucky section of Lower Shawneetown (that was the main village of the Shawnee during the 18th Century) was established. Dr. Thomas Walker, a Virginia surveyor, led the first organized English expedition through the Cumberland Gap into what would eventually become Kentucky. -

Seth Eastman a Biography Fort Snelling & the Dakota People Timeline

Seth Eastman a biography Fort Snelling & the Dakota People Timeline Seth Eastman was born on January 24, 1808, in Brunswick, Maine. The oldest The artist returned to West Fort Snelling was constructed in 1820 at the confluence of thirteen children, he became interested in joining the military at an early Point to teach drawing of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, a site which had age. He entered West Point Military Academy at sixteen and spent five years in 1833, and shortly been occupied by humans for thousands of years. It was a 1800 studying sketching and topography. After graduating in 1830, the military afterwards, in 1835, self-contained community, with a blacksmith, doctor, and transferred him to Fort Snelling in what is now Saint Paul, Minnesota. Fort married his second wife. barber living at the Fort. Men assigned there resided in the Snelling was first established after the War of 1812 to help control the fur Mary Henderson (1818– barracks with their families. Seth Eastman was stationed trade between Indigenous peoples and American fur traders, as well as to 1887), the daughter of there twice: his first assignment was 1830–1832, and maintain a line of defense against the British troops in the Northwest. During a military surgeon, was his second was 1841–1848 where he served as the Fort’s his time stationed there, Eastman familiarized himself with native culture, also interested in Native commander four times. The years he spent at Fort Snelling 1808 Seth Eastman was born on studying the language as well as the traditional dress and lifestyle of the local American culture and deeply influenced his art. -

The Parks Bloomington Has Section Contents History of Bloomington’S Park System 40

02 02 THE PARKS BLOOMINGTON HAS SECTION CONTENTS HISTORY OF BLOOMINGTON’S PARK SYSTEM 40 ELEMENTS OF BLOOMINGTON’S PARK SYSTEM 42 PROGRAM ASSESSMENT 84 COVID IMPACTS 92 SECTION 02 REFERENCES 94 THE PARKS BLOOMINGTON HAS 39 1 HISTORY OF BLOOMINGTON’S PARK PARK PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT AMERICAN BLVD. SYSTEM 494 A Park Board was established in Bloomington Township in 1946 following 77 86TH ST. the dedication of Beaverbrook and Lower Bryant Parks. The Park and 90TH ST. 90TH ST. 02 Recreation Advisory Commission was later established in 1955 and the 35W OLD CEDAR AVE. LYNDALE AVE. first park land purchase was made in 1954 for 28 acres of Moir Park. In PORTLAND AVE. PENN AVE. NORMANDALE BLVD. 98TH ST. 98TH ST. 1958, an ordinance was passed requiring park dedication from subdivision 169 FRANCE AVE. developers and the City used this dedicated land or money from developers to create a majority of the Bloomington park system. The 1960’s and OLD SHAKOPEE RD. 1970’s included a number of successful park bond referendums, grants, and land acquisitions. The Federal Land and Water Conservation Program 1940’s & 1950’s Grid-Like (LAWCON) was created in the 1970’s and provided grant opportunities Development to acquire parks and recreational areas. North Corridor Park, Tierney’s 0 1 Mile Development responds to topography Woods, Pond-Dakota Mission Park, and Marsh Park were purchased with Figure 2-1: Pattern of Development and natural features support from LAWCON. State and Metropolitan Council funding helped create the Hyland-Bush-Anderson Lakes Park Reserve and the Minnesota Patterns of development in Bloomington occurred based on location of Valley National Wildlife Refuge. -

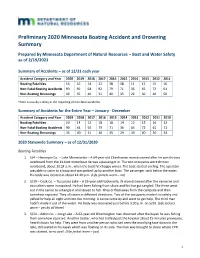

2020 Minnesota Boating Accident and Drowning Summary

, Preliminary 2020 Minnesota Boating Accident and Drowning Summary Prepared by Minnesota Department of Natural Resources – Boat and Water Safety as of 2/19/2021 Summary of Accidents – as of 12/31 each year Accident Category and Year 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 Boating Fatalities 16 10 14 12 18 18 14 12 15 16 Non-Fatal Boating Accidents 90 90 64 92 79 71 36 65 72 61 Non-Boating Drownings 49 35 40 31 40 35 29 30 40 50 There is usually a delay in the reporting of non-fatal accidents. Summary of Accidents for the Entire Year – January - December Accident Category and Year 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 Boating Fatalities 10 14 12 18 18 14 12 15 16 12 Non-Fatal Boating Accidents 90 64 92 79 71 36 65 72 61 71 Non-Boating Drownings 35 40 31 40 35 29 30 40 50 34 2020 Statewide Summary – as of 12/31/2020 Boating Fatalities 1. 5/4 – Hennepin Co. – Lake Minnetonka – A 64-year-old Chanhassen man drowned after he was thrown overboard from the 14-foot motorboat he was a passenger in. The two occupants were thrown overboard, about 10:24 a.m., when the boat hit choppy waves. The boat started circling. The operator was able to swim to a buoy and was picked up by another boat. The passenger sank below the water. His body was located at about 12:40 p.m. (Life jackets worn – no) 2. 5/19 – Cook Co. -

The United States

Bulletin No. 226 . Series F, Geography, 37 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES V. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR BOUNDARIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND OF THE SEVERAL STATES AND TERRITORIES WITH AN OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF ALL IMPORTANT CHANGES OF TERRITORY (THIRD EDITION) BY HENRY G-ANNETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 CONTENTS. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................... ............. 7 CHAPTER I. Boundaries of the United States, and additions to its territory .. 9 Boundaries of the United States....................................... 9 Provisional treaty Avith Great Britain...........................'... 9 Treaty with Spain of 1798......................................... 10 Definitive treaty with Great Britain................................ 10 Treaty of London, 1794 ........................................... 10 Treaty of Ghent................................................... 11 Arbitration by King of the Netherlands............................ 16 Treaty with Grreat Britain, 1842 ................................... 17 Webster-Ash burton treaty with Great Britain, 1846................. 19 Additions to the territory of the United States ......................... 19 Louisiana purchase................................................. 19 Florida purchase................................................... 22 Texas accession .............................I.................... 23 First Mexican cession....... ...................................... 23 Gadsden purchase............................................... -

Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA

Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA WHITE PAPER PREPARED FOR THE U.S. GLOBAL CHANGE RESEARCH PROGRAM NATIONAL CLIMATE ASSESSMENT MIDWEST TECHNICAL INPUT REPORT Jeff Andresen1,2, Steve Hilberg3, and Ken Kunkel4 1 Michigan State Climatologist 2 Michigan State University 3 Midwest Regional Climate Center 4 Desert Research Institute Recommended Citation: Andresen, J., S. Hilberg, K. Kunkel, 2012: Historical Climate and Climate Trends in the Midwestern USA. In: U.S. National Climate Assessment Midwest Technical Input Report. J. Winkler, J. Andresen, J. Hatfield, D. Bidwell, and D. Brown, coordinators. Available from the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLISA) Center, http://glisa.msu.edu/docs/NCA/MTIT_Historical.pdf. At the request of the U.S. Global Change Research Program, the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Center (GLISA) and the National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment formed a Midwest regional team to provide technical input to the National Climate Assessment (NCA). In March 2012, the team submitted their report to the NCA Development and Advisory Committee. This white paper is one chapter from the report, focusing on potential impacts, vulnerabilities, and adaptation options to climate variability and change for the historical climate sector. U.S. National Climate Assessment: Midwest Technical Input Report: Historical Climate Sector White Paper Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Package 'Maps'

Package ‘maps’ September 25, 2021 Title Draw Geographical Maps Version 3.4.0 Date 2021-09-25 Author Original S code by Richard A. Becker and Allan R. Wilks. R version by Ray Brownrigg. Enhancements by Thomas P Minka and Alex Deckmyn. Description Display of maps. Projection code and larger maps are in separate packages ('mapproj' and 'mapdata'). Depends R (>= 3.5.0) Imports graphics, utils LazyData yes Suggests mapproj (>= 1.2-0), mapdata (>= 2.3.0), sp, rnaturalearth License GPL-2 Maintainer Alex Deckmyn <[email protected]> NeedsCompilation yes Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2021-09-25 20:40:03 UTC R topics documented: area.map . .2 canada.cities . .3 county . .4 county.fips . .5 france . .5 identify.map . .6 iso.expand . .7 iso3166 . .9 italy . 10 lakes............................................. 11 map ............................................. 12 1 2 area.map map.axes . 16 map.cities . 17 map.scale . 19 map.text . 20 map.where . 21 match.map . 22 nz .............................................. 23 ozone . 24 smooth.map . 24 Spatial2map . 26 state . 27 state.carto . 28 state.fips . 29 state.vbm . 29 us.cities . 30 usa.............................................. 31 world ............................................ 32 world.cities . 33 world2 . 34 Index 36 area.map Area of projected map regions Description Computes the areas of regions in a projected map. Usage area.map(m, regions = ".", sqmi=TRUE, ...) Arguments m a map object containing named polygons (created with fill = TRUE). regions a character vector naming one of more regions, as in map. sqmi If TRUE, measure area in square miles. Otherwise keep the units of m. ... additional arguments to match.map Details The area of each matching region in the map is computed, and regions which match the same ele- ment of regions have their areas combined.