Clarinetist and Teacher, Contributions And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives

Pftft.. Slower • .. ina• alumna •••• ■■••••■•••=411• 'I 4 mp • • ••• •• Mman•IMMIln. • ■•••••■•■ ••••■••■•••■•••■■ •••• =Mr • NOW". • • =Mir • 11••■••••■••1111••••1•11• ■•111•141•111111 NUM/ 11/MIIMIN MAIMM•MIM / •• la. ••MINM/ ..MIN MI ••`' GAM MI =MO OW GM womall AMMONIUM mm,•••• ■• ".••••• rnio gradually taster 111•^ •IIMI ._./Mat MINNIP MUM OM -AM DINIIMINIMP MAIIIIIMINIMIMM•••••■ •1•1 MM. IMMIMMIIMMIO MM. MIIMMIMMO IMMIN••••••• OPP"' a tempo (lively) 111111.1. -.la a ••••••••■• • •• . • •■•■ 011•1111111MMIMINIAMmIM m••• ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ np. ••••• •••• A •• •• •••• • •• •11 OM MI MI MOM MOMMIll NI . •• maim ININIMIMMIM. ••• s4•4411•1• / a Ma . (1.• • •,41411•1~m MIHM11.11•••• 0 ■• IL • u damns. ••••■••••••••••• ••••• • •-••••,••• .ma• • ...•••■•••••••• mar- ••••• • • •••111111 • 4 . • 11.1111.1111111 Man a 4.M1 ... OM • 1■•••• ■••■=1IN•1•11••11 •IIMMIMIMMINIIIIIIMINIM-1• •••••••••••••••• NOMIM MAIM AMU MIMI MID IIIMIIIIP - IIIIIIMMIDIMIU•MIME V- • . • • 1•■•••■•••• al•IIMIMIIIII••••••••• ••••■••••••••• V M-4111•1111•111•IM • MS MI••••••■ •••• MMUMMIIMINAMMOMIIM •■•• • ••••■•• MINIam•• • • M ■•■•■ ••••••111M4•• IIIMIll. 111111.111. 511111.1111 111 ads MIIMNIM■• ■ • I 1••••••• IMAMS •111.401MMIIIIMI IIMI ■MIIIMMIMIMM • -.MMMMIMI ••• MINIMMOINNIMMIIMMMIIIMUM- ONO WM. Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor 16, 18, 21 October 1975 at 8:30 pm 17 October 1975 at 2:00 pm 25 November 1975 at 7:30 pm Symphony Hall, Boston Ninety-fifth season -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1962 Sonata for Clarinet Choir Donald S. Lewellen Eastern Illinois University Recommended Citation Lewellen, Donald S., "Sonata for Clarinet Choir" (1962). Masters Theses. 4371. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4371 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -SONATA POR CLARINET CHOIR A PAPER PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF TILE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF TIIB REQUIREMENTS FOR IBE DEGREE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN EDUCATION DONALDS. LEWELLEN '""'."'.···-,-·. JULY, 1962' TABLE OF CONTENTS :le Page • • • • • • • . • .. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • i ile of Contents . .. ii iface ••.•....•...•........••....... •· ...•......•.•...• iii ::tion I ! Orchestra and Band ································· 1 lrinet Choir New Concept of Sound •••••••••••••••••• 2 3.rinet Choir Medium of Musical Expression . .. 2 arinet Choir Instrumentation . 3 ction II nata for Clarinet Choir - Analysis . .. 6 mmary • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 bliography ••••.•••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••• 10 PREFACE The available literature for clarinet choir is quite limited, and much of this literature is an arrangement of orchestral music. -

PIAZZOLLA CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION Saturday, March 13, 2021 at 7:30 Pm

PIAZZOLLA CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION Saturday, March 13, 2021 at 7:30 pm ALLEN-BRADLEY HALL MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY POPS Stas Venglevski, bayan Frank Almond, violin Roza Borisova, cello Jeannie Yu, piano Verano Porteño .................................................................Astor Piazzolla Tanguera .............................................................................Mariano Mores Mumuki ................................................................................Astor Piazzolla Quejas de Bandoneón .................................... Juan de Dios Filiberto La Violetera ...............................................................................José Padilla El Choclo................................................................................Ángel Villoldo Jalousie “Tango Tzigane” ................................................. Jacob Gade La Cumparsita ............................................Gerardo Matos Rodríguez Fuga y Misterio ................................................................Astor Piazzolla Allegro Tangabile .............................................................Astor Piazzolla Gitanerias ...................................................................... Ernesto Lecuona Por Una Cabeza .................................................................Carlos Gardel The MSO Steinway piano was made possible through a generous gift from Michael and Jeanne Schmitz. The Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra’s Reimagined Season is sponsored by the United Performing Arts Fund. 1 MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA -

Kimberly Cole Luevano, DMA

Kimberly Cole Luevano, DMA College of Music 1809 Goshawk Lane University of North Texas Corinth, TX 76210 Denton, TX 76203 734.678.9898 940.565.4096 [email protected] [email protected] Present Appointments University of North Texas, Denton, TX. Professor 2018-present Associate Professor 2012-2018 Assistant Professor 2011-2012 Responsibilities include: • Teaching Applied Clarinet lessons. • Teaching Doctoral Clarinet Literature course (MUAG 6360). • Teaching pedagogy courses as needed (MUAG 4360/5360). • Serving on graduate student recital and exam committees. • Advising doctoral students in development and completion of dissertation work. • Assisting in coordination of instruction of clarinet concentration lessons, clarinet secondary lessons, clarinet minor lessons, and all clarinet jury examinations. • Assisting in oversight of graduate Teaching Fellow position. • Collaborating with faculty colleagues in their performances. • Assisting in instruction of woodwinds methods classes as needed. • Coaching student chamber ensembles as needed. • Recruitment and development of the clarinet studio. • Listening to ensemble auditions for placement of clarinetists in ensembles. Director: UNT ClarEssentials Summer Workshop 2011- 2018 • Artistic direction, administration, and oversight of all aspects of the 5-day on- campus event for high school clarinetists. Haven Trio (Lindsay Kesselman, soprano; Midori Koga, piano). 2012-present TrioPolis Trio (Felix Olschofka, violin; Anatolia Ioannides, piano) 2016-present Artist Clinician: Henri Selmer-Paris 2015 – present Artist Clinician: Conn-Selmer USA 2015 – present Artist Clinician: The D’Addario Company 2013- present Education Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Clarinet Performance, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. 1996 Master of Music degree in Clarinet Performance, Music History concentration, Michigan State University. 1994 Postgraduate Study, L’Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris, Paris, France. -

Program Notes

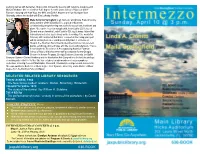

studying clarinet with her father, Nick Cionitti, followed by lessons with Valentine Anzalone and Michael Webster. She received her B.M. degree from the Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, studying with Alan Woy. Her M.M. and D.M.A. degrees are from Michigan State University, where she studied with Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr. Maila Gutierrez Springfield is an instructor at Valdosta State University and a member of the Maharlika Trio, a group dedicated to commissioning and performing new works for saxophone, trombone and piano. She can be heard on saxophonist Joren Cain’s CD Voices of Dissent and on clarinetist Linda Cionitti’s CD Jag & Jersey. MusicWeb International selected Jag & Jersey as the recording of the month for February 2010 and noted that Maila “is superb in the taxing piano part with its striding bass lines and disjointed rhythms”. For Voices of Dissent, the American Record Guide describes Maila as “an excellent pianist, exhibiting solid technique and fine touch and pedal work." Twice- honored with the Excellence in Accompanying Award at Eastman School of Music, Maila has been staff accompanist for the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program, Georgia Southern University, the Buffet Crampon Summer Clarinet Academy and the Interlochen Arts Camp where she had the privilege of working with cellist Yo-Yo Ma. She has collaborated with members of major symphony orchestras, including those in Philadelphia, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Jacksonville. She was awarded a Bachelor of Music degree from Syracuse University, and a Master of Music degree from the Eastman School of Music. SELECTED RELATED LIBRARY RESOURCES 780.92 A1N532, 1984 The New Grove modern masters : Bartók, Stravinsky, Hindemith 788.620712 S932s 1970 The study of the clarinet / by William H. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

O Ensino Da Clarineta Em Nível Superior: Materiais Didáticos E O Desenvolvimento Técnico-Interpretativo Do Clarinetista

Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima João Pessoa Março de 2019 Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima Orientador: Dr. Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, área de concentração em Educação Musical. João Pessoa Março de 2019 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação L732e Lima, Eduardo Filippe de. O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista / Eduardo Filippe de Lima. - João Pessoa, 2019. 111f. : il. Orientação: Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro. Dissertação (Mestrado) - UFPB/CCTA. 1. Ensino de instrumento musical. 2. Ensino da clarineta em nível superior. 3. Materiais didáticos para clarineta. 4. Desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinet. I. Ribeiro, Fábio Henrique Gomes. II. Título. UFPB/BC 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de agradecer imensamente a todos que contribuíram de maneira direta e indireta para a conclusão desse curso de mestrado, o qual me trouxe um profundo amadurecimento pessoal e profissional, e que simboliza o encerramento de mais um ciclo na minha carreira musical. À minha família, que sempre me deu apoio e o suporte necessário para continuar com todos os meus projetos, incluindo esse curso; Ao meu orientador, prof. -

Download the Clarinet Saxophone Classics Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2017 www.samekmusic.com Founded in 1992 by acclaimed clarinetist Victoria Soames Samek, Clarinet & Saxophone Classics celebrates the single reed in all its richness and diversity. It’s a unique specialist label devoted to releasing top quality recordings by the finest artists of today on modern and period instruments, as well as sympathetically restored historical recordings of great figures from the past supported by informative notes. Having created her own brand, Samek Music, Victoria is committed to excellence through recordings, publications, learning resources and live performances. Samek Music is dedicated to the clarinet and saxophone, giving a focus for the wonderful world of the single reed. www.samek music.com For further details contact Victoria Soames Samek, Managing Director and Artistic Director Tel: + 44 (0) 20 8472 2057 • Mobile + 44 (0) 7730 987103 • [email protected] • www.samekmusic.com Central Clarinet Repertoire 1 CC0001 COPLAND: SONATA FOR CLARINET Clarinet Music by Les Six PREMIERE RECORDING Featuring the World Premiere recording of Copland’s own reworking of his Violin Sonata, this exciting disc also has the complete music for clarinet and piano of the French group known as ‘Les Six’. Aaron Copland Sonata (premiere recording); Francis Poulenc Sonata; Germaine Tailleferre Arabesque, Sonata; Arthur Honegger Sonatine; Darius Milhaud Duo Concertant, Sonatine Victoria Soames Samek clarinet, Julius Drake piano ‘Most sheerly seductive record of the year.’ THE SUNDAY TIMES CC0011 SOLOS DE CONCOURS Brought together for the first time on CD – a fascinating collection of pieces written for the final year students studying at the paris conservatoire for the Premier Prix, by some of the most prominent French composers.