Tembo, K.D. Pax in Terra:

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Superman-The Movie: Extended Cut the Music Mystery

SUPERMAN-THE MOVIE: EXTENDED CUT THE MUSIC MYSTERY An exclusive analysis for CapedWonder™.com by Jim Bowers and Bill Williams NOTE FROM JIM BOWERS, EDITOR, CAPEDWONDER™.COM: Hi Fans! Before you begin reading this article, please know that I am thrilled with this new release from the Warner Archive Collection. It is absolutely wonderful to finally be able to enjoy so many fun TV cut scenes in widescreen! I HIGHLY recommend adding this essential home video release to your personal collection; do it soon so the Warner Bros. folks will know that there is still a great deal of interest in vintage films. The release is only on Blu-ray format (for now at least), and only available for purchase on-line Yes! We DO Believe A Man Can Fly! Thanks! Jim It goes without saying that one of John Williams’ most epic and influential film scores of all time is his score for the first “Superman” film. To this day it remains as iconic as the film itself. From the Ruby- Spears animated series to “Seinfeld” to “Smallville” and its reappearance in “Superman Returns”, its status in popular culture continues to resonate. Danny Elfman has also said that it will appear in the forthcoming “Justice League” film. When word was released in September 2017 that Warner Home Video announced plans to release a new two-disc Blu-ray of “Superman” as part of the Warner Archive Collection, fans around the world rejoiced with excitement at the news that the 188-minute extended version of the film - a slightly shorter version of which was first broadcast on ABC-TV on February 7 & 8, 1982 - would be part of the release. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

The Return of Superman: the Return of Superman Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SUPERMAN THE RETURN OF SUPERMAN: THE RETURN OF SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jon Bogdanove,Tom Grummett,Gerard Jones,Dan Jurgens,Karl Kesel,Jeph Loeb | 480 pages | 24 May 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401266622 | English | United States Superman the Return of Superman: The Return of Superman PDF Book Marlon Brando appears posthumously as Jor-El , Superman's biological father. But will he be too late to save Coast City from the clutches of a traitor and the return of the alien warlord, Mongul? He'll take her on a shopping spree to her favorite character store to please her. Batman s Batman. December 23, Seeing Jason seemingly have a slight reaction to Kryptonite, Luthor asks who Jason's father really is; Lois asserts that the father is Richard. Park Hyun-bin Trot singer. The New York Times. While visiting a traditional Korean sauna, Seoeon pulled on older girls to play with him. And then go off to play on his own without waking his family up. Even father Hwijae is put to the side once he sees a cute female. In an attempt to protect the world he loves from cataclysmic destruction, Superman embarks on an epic journey of redemption that takes him from the depths of the ocean to the far reaches of outer space. Following a mysterious absence of several years, the Man of Steel comes back to Earth in the epic action-adventure Superman Returns, a soaring new chapter in the saga of one of the world's most beloved superheroes. The phrase has become a special saying between Hwijae and the triplets. -

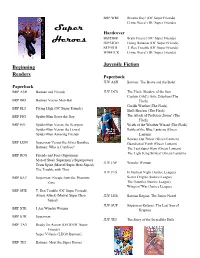

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Thinking About Journalism with Superman 132

Thinking about Journalism with Superman 132 Thinking about Journalism with Superman Matthew C. Ehrlich Professor Department of Journalism University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL [email protected] Superman is an icon of American popular culture—variously described as being “better known than the president of the United States [and] more familiar to school children than Abraham Lincoln,” a “triumphant mixture of marketing and imagination, familiar all around the world and re-created for generation after generation,” an “ideal, a hope and a dream, the fantasy of millions,” and a symbol of “our universal longing for perfection, for wisdom and power used in service of the human race.”1 As such, the character offers “clues to hopes and tensions within the current American consciousness,” including the “tensions between our mythic values and the requirements of a democratic society.”2 This paper uses Superman as a way of thinking about journalism, following the tradition of cultural and critical studies that uses media artifacts as tools “to size up the shape, character, and direction of society itself.”3 Superman’s alter ego Clark Kent is of course a reporter for a daily newspaper (and at times for TV news as well), and many of his closest friends and colleagues are also journalists. However, although many scholars have analyzed the Superman mythology, not so many have systematically analyzed what it might say about the real-world press. The paper draws upon Superman’s multiple incarnations over the years in comics, radio, movies, and television in the context of past research and criticism regarding the popular culture phenomenon. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Superman Ii the Richard Donner Cut Mp4 Download Please Enable Your VPN When Downloading Torrents

superman ii the richard donner cut mp4 download Please enable your VPN when downloading torrents. If you torrent without a VPN, your ISP can see that you're torrenting and may throttle your connection and get fined by legal action! Loading, please wait. Synopsis. Picking up where "Superman: The Movie" left off, three criminals, General Zod (Terence Stamp), Ursa, (Sarah Douglas), and Non (Jack O'Halloran) from the planet Krypton are released from the Phantom Zone by a nuclear explosion in space. They descend upon Earth where they could finally rule. Superman, meanwhile, is in love with Lois Lane (Margot Kidder), who finds out who he really is. Lex Luthor (Gene Hackman) escapes from prison and is determined to destroy Superman by joining forces with the three criminals. —Keith Howley. Picking up where "Superman: The Movie" left off, three criminals, General Zod (Terence Stamp), Ursa, (Sarah Douglas), and Non (Jack O'Halloran) from the planet Krypton are released from the Phantom Zone by a nuclear explosion in space. They descend upon Earth where they could finally rule. Superman, meanwhile, is in love with Lois Lane (Margot Kidder), who finds out who he really is. Lex Luthor (Gene Hackman) escapes from prison and is determined to destroy Superman by joining forces with the three criminals. —Keith Howley. Uploaded By: OTTO April 04, 2019 at 04:21 AM. Director. Tech specs. Movie Reviews. Great film. Simply put, Superman II is one of the best action/comic-oriented films of all time. I'd rank it second only to the original Superman: The Movie and only X-Men is right up there. -

Kirby Letterhead

SUPERGIRL IN THE BRONZE AGE! October 2015 No.84 $ 8 . 9 5 Supergirl TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 Pre-Crisis Supergirl I Death of Supergirl I Rebirths of Supergirl I Superwoman ALAN BRENNERT interview I HELEN SLATER Supergirl movie & more super-stuff! 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 84 October 2015 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow TM DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Karl Heitmueller, Jr., with Stephen DeStefano Bob Fingerman Dean Haspiel Kristen McCabe Jon Morris Jackson Publick COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER John Morrow SPECIAL THANKS Cary Bates Elliot S. Maggin Alan Brennert Andy Mangels ByrneRobotics.com Franck Martini BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Glen Cadigan Jerry Ordway FLASHBACK: Supergirl in Bronze . .3 and The Legion George Pérez The Maid of Might in the ’70s and ’80s Companion Ilya Salkind Shaun Clancy Anthony Snyder PRINCE STREET NEWS: The Sartorial Story of the Sundry Supergirls . .24 Gary Colabuono Roger Stern Oh, what to wear, what to wear? Fred Danvers Jeannot Szwarc DC Comics Steven Thompson THE TOY BOX: Material (Super) Girl: Pre-Crisis Supergirl Merchandise . .26 Jim Ford Jim Tyler Dust off some shelf space, ’cause you’re gonna want this stuff Chris Franklin Orlando Watkins FLASHBACK: Who is Superwoman? . .31 Grand Comics John Wells Database Marv Wolfman Elliot Maggin’s Miracle Monday heroine, Kristen Wells Robert Greenberger BACKSTAGE PASS: Adventure Runs in the Family: The Saga of the Supergirl Movie . .35 Karl Heitmueller, Jr. Hollywood’s Ilya Salkind and Jeannot Szwarc take us behind the scenes Heritage Comics Auctions FLASHBACK: Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 . -

Superman: Earth One: Volume 3 Free

FREE SUPERMAN: EARTH ONE: VOLUME 3 PDF Ardian Syaf,J. Michael Straczynski | 128 pages | 17 Feb 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401241841 | English | United States Superman: Earth One Vol. 3 by J. Michael Straczynski, Ardian Syaf, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Superman: Earth One is a series of graphic novels written by J. Michael Straczynski and illustrated by Shane Davis. Superman: Earth One was the inaugural title of the new, ongoing graphic novel series Earth One. Writer J. Michael Straczynski said the project was a Superman: Earth One: Volume 3 come true, as writing Superman was among his plans which also included Babylon 5. Two years before its publication, Straczynski announced he had signed a contract with DC Comics. Before Straczynski's announcement, he had kept the project secret while he worked on the Red Circle characters and The Brave and the Bold. Straczynski used his experiences as a journalist to add detail to the Daily Planet environment, for example, the character Jimmy Olsencalled Jim in the books, is depicted as tougher and smarter than his mainstream counterpart. Straczynski wanted to retell the beginning of Clark Kent's transition to Superman, and explore possible alternatives to Clark becoming a superhero. Straczynski said; "he [Kent] could have been rich as an athlete, researcher, any number of things. Superman: Earth One: Volume 3 a flashback scene to when Martha Kent finishes his uniform and gives it to him as a gift, hoping he will go that way. He looks at it and says, in essence, 'Shouldn't there be a mask? The mask Straczynski introduced a new villain character with a connection to Kryptonwho was used to explain its destruction. -

The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 10 Issue 2 October 2006 Article 6 October 2006 The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2006) "The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol10/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Superhero's Mythic Journey: Death and the Heroic Cycle in Superman Abstract Superman, the original superhero, is a culmination of the great mythic heroes of the past. The hero's journey, a recurring cycle of events in mythology, is described by Joseph Campbell. The three acts in Superman: The Movie portray a complex calling to the superhero's role, consisting of three distinct calls and journeys. Each of the three stages includes the death of someone close to him, different symbols of his own death and resurrection, and different experiences of atonement with a father figure. Analyzing these mythic cycles bestows the viewer with a heroic "elixir.” This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol10/iss2/6 Stucky: The Superhero's Mythic Journey Introduction Since 1938, Superman has been popular culture's paradigmatic hero, and the original superhero has lived in many forms of media, from comic books to television series to film versions that include the 2006 Superman Returns.1 His story is a culmination of the great mythic heroes of the past. -

Blockbuster Mentality Among the Hollywood Studios

BLOCK BUSTER Abstract: This article explores the often contradictory relationship between films and comic book art. Adaptations of superhero comics have reinforced a commercialistic blockbuster mentality among the Hollywood studios. Adapta- tions of graphic novels have explored alternate visions of visual style and A comic book superhero, brought to life on the big screen. representation. Complications of these polarized effects and subsequent impli- cations will be discussed. year (Prince 5)—was X-Men: The Last weekend. X3, a Twentieth Century Stand (X3). Based on characters owned Fox release, had the full promotional Key words: blockbuster, comic books, by Marvel Entertainment, the largest power of Rupert Murdoch’s News film, graphic novels, superhero. U.S. comics publisher with approxi- Corp. behind it, which included tie-ins mately 37% of the market, X3 dem- with popular Fox network programs ummer 2006 waswas a telling season onstrated the huge amount of money American Idol, The Simpsons, and for the often polarized nature involved in producing a Hollywood Family Guy; local promotional news S of comic book-related movies,movies, blockbuster. X3 cost over $200 million stories on television affiliates; and as a comparison of twtwoo U.S. releases to make, showed in more than 3,700 an X3 page on the NewsCorp-owned indicates. A major studio “tentpole” U.S. theaters, and set a Memorial Day Web site MySpace.com (Angwin B3; release—a high-profile film with the box office record with an intake of $122 Johnson). The movie’s reviews were economic potential to singlehandedly million in four days (Kaltenbach 1). -

How to Be a Hero: a Rhetorical Analysis of Superman's First Appearance In

HOW TO BE A HERO: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF SUPERMAN’S FIRST APPEARANCE IN ACTION COMICS By Sevan Michael Paris Approved: Lauren Ingraham Susan North Professor of Rhetoric and Composition Assistant Professor of Rhetoric and (Director of Thesis) Composition (Committee Member) Bonnie Warren-Kring Associate Professor of Education (Committee Member) Herb Burhenn A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the College of Arts and Dean of the Graduate School Sciences i HOW TO BE A HERO: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF SUPERMAN’S FIRST APPEARANCE IN ACTION COMICS By Sevan Michael Paris A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Rhetoric and Writing University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee ii ABSTRACT Through a combination of rhetorical heightening, idiom, and structure, Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster influenced their young American audience with the first appearance of Superman in 1938’s Action Comics no. 1. Superman’s lack of distinguishing characteristics, dual identity, and embodiment of American culture allowed the character to become a vehicle for Siegel and Shuster, persuading children to be a helper of those in need and champion of the oppressed. Varying panel size and choosing what to show from what not to show allowed Siegel and Shuster to heighten specific moments within Superman’s story. Through metaphor and symbolic modeling, children recognized the impact of helping others in their lives both as a child and later as an adult. The tools that Siegel and Shuster had available to them in this particular medium—such as being able to simultaneously heighten several different moments within the narrative in one panel—make it a unique form of rhetorical heightening in fiction.