Linguistic Appropriation, White Privilege, and the Hip-Hop Persona of Iggy Azalea1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Many Faces of Knowledge Production in Art Museums: an Exploration of Exhibition Strategies Emilie Sitzia

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 18:10 Muséologies Les cahiers d'études supérieures The Many Faces of Knowledge Production in Art Museums: An Exploration of Exhibition Strategies Emilie Sitzia Les nouveaux paradigmes Volume 8, numéro 2, 2016 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050765ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1050765ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Association Québécoise de Promotion des Recherches Étudiantes en Muséologie (AQPREM) ISSN 1718-5181 (imprimé) 1929-7815 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Sitzia, E. (2016). The Many Faces of Knowledge Production in Art Museums: An Exploration of Exhibition Strategies. Muséologies, 8(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050765ar Tous droits réservés © Association Québécoise de Promotion des Recherches Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des Étudiantes en Muséologie (AQPREM), 2018 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Article cinq The Many Faces of Knowledge Production in Art Museums: An Exploration of Exhibition Strategies Emilie Sitzia 141 Muséologies vol. 8 | no 2 Article cinq (141 – 157) Dr. Emilie Sitzia is an associate professor in the depart- ment of literature and art at Maastricht University and the director of the Master Arts and Heritage programme. -

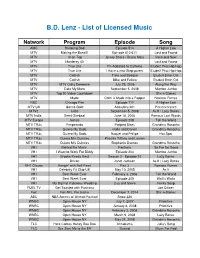

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Classic Albums: the Berlin/Germany Edition

Course Title Classic Albums: The Berlin/Germany Edition Course Number REMU-UT 9817 D01 Spring 2019 Syllabus last updated on: 23-Dec-2018 Lecturer Contact Information Course Details Wednesdays, 6:15pm to 7:30pm (14 weeks) Location NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room BLAC 101 Prerequisites No pre-requisites Units earned 2 credits Course Description A classic album is one that has been deemed by many —or even just a select influential few — as a standard bearer within or without its genre. In this class—a companion to the Classic Albums class offered in New York—we will look and listen at a selection of classic albums recorded in Berlin, or recorded in Germany more broadly, and how the city/country shaped them – from David Bowie's famous Berlin trilogy from 1977 – 79 to Ricardo Villalobos' minimal house masterpiece Alcachofa. We will deconstruct the music and production of these albums, putting them in full social and political context and exploring the range of reasons why they have garnered classic status. Artists, producers and engineers involved in the making of these albums will be invited to discuss their seminal works with the students. Along the way we will also consider the history of German electronic music. We will particularly look at how electronic music developed in Germany before the advent of house and techno in the late 1980s as well as the arrival of Techno, a new musical movement, and new technology in Berlin and Germany in the turbulent years after the Fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, up to the present. -

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

Distinguished Artists Concert Series

Supervisor JOSEPH SALADINO presents 2018 - 2019 Distinguished Artists Concert Series Co-Sponsoring Libraries Bethpage • Farmingdale • Hicksville • Jericho • Locust Valley Massapequa • Plainview-Old Bethpage • Syosset A Message from Joseph Saladino Town Supervisor Dear Neighbor, The Town of Oyster Bay2018-2019 Distinguished Artists Concert series will, once again, offer a diverse season of musical programs, which will kick off in October. Whatever your musical taste, Opera, Pop, Jazz, Classical or anything in between, there is something for everyone. The concert season begins on Sunday, October 7, 2018 at the Locust Valley Library with Mambo Loco performing Old-School Latin & Latin Jazz and continues through Sunday, May 19, 2019 culminating with a performance by Just Sixties - a multi-media retrospective of the 1960’s. This season’s lineup also includes The Hambones - Country/Rockabilly, River of Dreams - a tribute to the music of Billy Joel, The Tribunes - authentic Street Corner Harmony, New Vintage Orchestra performing Swing & Jazz Hits of a Lifetime, and Sasha Papernik & Her Band - an homage to Burt Bacharach & Hal David, just to name a few. My fellow Town Board members and I are proud to provide residents with some of the very finest cultural and performing arts entertainment available. All concerts are free of charge and are held at conveniently-located local libraries throughout the Town. Please take a few moments to glance through the brochure and begin planning your entertainment schedule. We look forward to seeing you at the -

Presenting Our 29Th Season

PRESENTING OUR 29TH SEASON DEC 7-8 This December, it’s a Queen City Christmas! From Ruth Lyons to Doris Day to Rosemary Clooney, the tri-state has a rich history of brilliant artists worthy of celebrating. Join us as we pay tribute to our ADVERTISER FACTSHEET hometown heroes! For 29 years the Cincinnati Men’s Chorus has provided a non-confrontational voice to the issues of the GBTLQ+ community. One of the key sources of revenue that allows us to continue this important mission is the sale of APR 4-5 advertising in our Concert Programs. In spring, we’ll hop across the pond for God Save the Queens! The Beatles, Blur, the Spice Girls, Little To celebrate our 29th season of music we bring you THE SEASON OF THE Mix, Dusty Springfield, Adele, Elton John, George QUEENS! Performing in iconic locations throughout our Queen City. Kicking Michael, Sam Smith, Benjamin Britten: these artists off our concerts will be Queen City Christmas in the beginning of December continue to define the British Invasion! This trip will at The Carnegie in Covington, KY. Secondly as the seasons change our leave you feeling jolly good, without a hint of jetlag! spring concert, God Save the Queens will be held at the historic Walnut Hills High School, Westheimer Auditorium. June = Pride. We are hosting our first ever Big Gay Sing with Dancing Queens at Memorial Hall in Over the Rhine. JUN 20-21 Each of our concert weekends bring a diverse group of over 600 audience members, volunteers and performers into downtown and expose them to the Finally, for our Pride concert, CMC brings you our first companies and brands that support the CMC by advertising in our Concert Big Gay Sing with Dancing Queens! What’s a Big Gay Programs. -

From Face-Morphing to Speed- Reading, the 10 Best Apps of 2014

05/12/2018, 0040 Page 1 of 1 CULTURE From Face-Morphing to Speed- Reading, the 10 Best Apps of 2014 DECEMBER 30, 2014 2:00 PM by FELICITY SARGENT m J f i Our ten favorite new apps of 2014 fall into two categories: apps that make our lives more convenient and apps that make our content more creative. We’ll kick off with creativity and conclude with convenience, in each case suggesting some features that could make these apps even better next year. PHHHOTO In a Nutshell: instantly adds movement to any scene and turns it into a captivating loop, which you can share on its own mobile social network, as a GIF in texts or emails, or as a video on social networks like Facebook and Instagram. Why It Made the List: It’s fun, fresh, the loops look really cool, and it’s a favorite of music and fashion royalty. Wishes for the New Year: an Android version, more cool filters, a strobe light mode that pulses the flash while you shoot for even more zing, and the ability to add tunes and beats to Phhhotos (you can practically already hear them popping off of **Katy Perry’**s and **Diplo’**s). SUPER In a Nutshell: prompts users to quickly make and share square cards that are a cross between memes, quotes, and pictures. The cards are shared on Super’s mobile social network and are also easily shareable on other social networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.). RELATED VIDEO Watch: Bella Hadid on Her 10-Pound Sewn-In Veil leaving with not that much hair. -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

EW Ghostwriter User Manual

USER MANUAL 1.0.2 EASTWEST | GHOSTWRITER IMPORTANT COMPATIBILITY NOTE! Our Revolutionary New Opus Software Engine Our brand new Opus software engine has been years in development, and replaces the Play engine. All EastWest Libraries (with the exception of the original Hollywood Orchestra, the original Hollywood Solo Instruments, and the MIDI Guitar Series) are supported in Opus, allowing them to take advantage of a faster, more powerful, more flexible, and better looking software engine. Opus comes with some incredible new features such as individual instrument down- loads, customized key-switches, new effects for the mixer page, scalable retina user interface upgrades for legacy products, a powerful new script language, and many more features that allow you to completely customize the sound of each instrument. It’s one of the most exciting developments in the history of our company and will be the launching pad for many exciting new products in the future. Using Opus and Play Together Opus and Play are two separate software products, anything you have saved in your projects will still load up inside the saved Play version of the plugins. You can update your current/existing projects to Opus if you so choose, or leave them saved within Play. After purchasing or upgrading to Opus you do not need to use Play, but it may be more convenient to make small adjustments to an older composition in your DAW loading the instruments saved in Play instead of replacing them with Opus. For any new composi- tion, just use Opus. A Note About User Manuals All EastWest Libraries have their own user manuals (like this one) that refer to instru- ments and controls that are specific to their respective libraries, as well as referencing the Play User Manual for controls that are common to all EastWest Libraries. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life.