T&F Inquiry Supplementary Letter 120124

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Wales Is Understood in the UK Is a Problem – Strengthening Welsh Media Is Part of the Solution

How Wales is understood in the UK is a problem – strengthening Welsh media is part of the solution blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/how-wales-is-understood-in-the-uk-is-a-problem/ 4/1/2017 A healthy democracy needs mechanisms that enable citizens to understand the political process and engage in the functioning of politics. But as simple as this may sound, achieving such an understanding is proving a major problem for Wales. Craig Johnson reflects on the broader problems caused by the inadequate reporting of Welsh politics UK-wide. It was recently announced that a new BBC TV channel will broadcast in Scotland from 2018. It will have a budget of £30m, roughly equivalent to that of BBC Four. Alongside that, Scotland will receive more money to make UK-wide programmes. Perhaps the most interesting development is that, included in the new channel’s scheduling is an hour-long news programme, edited and presented from Scotland. This brings with it 80 new journalist posts. Even if viewing figures on the new channel turn out to be low, it will still be a significant boost to Scotland’s journalism. This is great news for Scotland, with BBC Scotland’s Sarah Smith arguing that ‘for those who wanted a news programme reflecting the world from a Scottish perspective, produced and presented from Scotland – the BBC is now delivering what they asked for’. However, it begs the question: what about Wales? Just a day earlier, the BBC announced that an additional £8.5m would be spent in Wales on both news and entertainment English-language programming. -

English Is a Welsh Language

ENGLISH IS A WELSH LANGUAGE Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies Published in Wales by the Institute of Welsh Affairs. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers. © Institute of Welsh Affairs, 2009 ISBN: 978 1 904773 42 9 English is a Welsh language Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well-being of Wales. IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ tel 029 2066 0820 fax 029 2023 3741 email [email protected] web www.iwa.org.uk Contents 1 Preface 4 1/ English is a Welsh language, Geraint Talfan Davies 22 2/ Inventing Wales, Patrick Hannan 30 3/ The long goodbye, Kevin Williams 36 4/ Normal service, Dai Smith 44 5/ Small screen, big screen, Peter Edwards 50 6/ The drama of belonging, Catrin Clarke 54 7/ Convergent realities, John Geraint 62 8/ Standing up among the cogwheels, Colin Thomas 68 9/ Once upon a time, Trevor -

Pay TV Market Overview Annex 8 to Pay TV Market Investigation Consultation

Pay TV market overview Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation Publication date: 18 December 2007 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Contents Section Page 1 Introduction 1 2 History of multi-channel television in the UK 2 3 Television offerings available in the UK 22 4 Technology overview 60 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Section 1 1 Introduction 1.1 The aim of this annex is to provide an overview of the digital TV services available to UK consumers, with the main focus on pay TV services. 1.2 Section 2 describes the UK pay TV landscape, including the current environment and its historical development. It also sets out the supply chain and revenue flows in the chain. 1.3 Section 3 sets out detailed information about the main retail services provided over the UK’s TV platforms. This part examines each platform / retail provider in a similar way and includes information on: • platform coverage and geographical limitations; • subscription numbers (if publicly available) by platform and TV package; • the carriage of TV channels owned by the platform operators and rival platforms; • the availability of video on demand (VoD), digital video recorder (DVR), high definition (HD) and interactive services; • the availability of other communications services such as broadband, fixed line and mobile telephony services. 1.4 Section 4 provides an overview of relevant technologies and likely future developments. 1 Annex 8 to pay TV market investigation consultation - pay TV market overview Section 2 2 History of multi-channel television in the UK Introduction 2.1 Television in the UK is distributed using four main distribution technologies, through which a number of companies provide free-to-air (FTA) and pay TV services to consumers: • Terrestrial television is distributed in both analogue and digital formats. -

Building Public Value: Renewing the BBC for a Digital World

DP1153 BPV Frontcover.qxd 6/25/04 2:52 PM Page 1 Building public value Renewing the BBC for a digital world CONTENTS Chairman’s prologue 3 Overview and summary 5 PART I: The BBC’s purpose, role and vision 1 Why the BBC matters 25 2 Changing media in a changing society 48 3 Building public value in the future 60 4 Demonstrating public value 83 5 The breadth of BBC services 89 6 Renewing the BBC 98 7 Paying for BBC services 112 PART II: Governing the BBC 123 Conclusion 135 1 2 Chairman’s prologue The BBC does not have a monopoly on wisdom about its own future. This is a contribution to the debate over Charter renewal, not the last word. I look to a vigorous and informed public debate to produce the consensus about the future size, shape and mission of the BBC. This document is itself a consensus, arrived at after a vigorous debate inside the BBC, and represents the considered views of Governors and management. Part II – our proposals on governance – is, of course, entirely the responsibility of the Governors. At the heart of Building public value is a vision of a BBC that maintains the ideals of its founders, but a BBC renewed to deliver those ideals in a digital world. That world contains the potential for limitless individual consumer choice. But it also contains the possibility of broadcasting reduced to just another commodity, with profitability the sole measure of worth. A renewed BBC, placing the public interest before all else, will counterbalance that market-driven drift towards programme-making as a commodity. -

British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2003 a Year of Positives Annual Report

British Sky Broadcasting Group plc Annual Report and Accounts 2003 A year of positives Annual Report 01 Chairman’s Statement 02 A Year of Positives 04 Operating and Financial Review Programming 14 News 15 Sports 16 Entertainment 18 Movies 20 Digital Channel line-up Financial Statements 22 Directors’ Biographies 23 Directors’ Report 24 Corporate Governance 26 Report on Directors’ Remuneration 31 Directors’ Responsibilities Auditors’ Report 32 Consolidated Profit and Loss Account and Consolidated Statement of Total Recognised Gains and Losses 33 Consolidated Balance Sheet 34 Company Balance Sheet 35 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 36 Notes to Financial Statements 61 Five Year Summary 62 Shareholders’ Service 63 Corporate Shareholder Information Chairman’s Statement Rupert Murdoch, Chairman + A year of positives Sky’s excellent financial results for the year clearly demonstrate that we are starting to realise the benefit of our significant investment in digital television in Britain. Indeed throughout the last five years, Sky has always been the driving force behind making the UK the world leader in digital television, and I fully expect Sky to build on its market leadership to deliver increased financial and operational strength over the next year. The winning formula of offering an unrivalled entertainment product combined with excellent customer service has helped Sky to win many new customers and maintain world-class levels of customer loyalty. As a result, by the end of June 2003, Sky digital had reached over 6.8 million subscribers and succeeded in consistently outperforming its operational targets. With the Company poised to sign up its seven millionth customer later this calendar year, the focus is now on returning to, and exceeding, the levels of profitability previously achieved in analogue. -

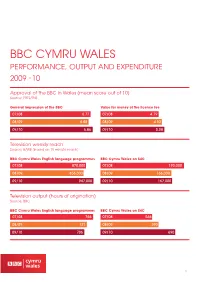

BBC CYMRU WALES Performance, Output and Expenditure 2009 - 10

BBC CYMRU WALES PERfoRMAnCE, oUtPUt And ExPEnditURE 2009 - 10 Approval of the BBC in Wales (mean score out of 10) Source: PBtS/tnS General impression of the BBC Value for money of the licence fee 07/08 6.77 07/08 4.79 08/09 6.68 08/09 4.93 09/10 6.86 09/10 5.08 television weekly reach Source: BARB (based on 15-minute reach) BBC Cymru Wales English language programmes BBC Cymru Wales on S4C 07/08 870,000 07/08 193,000 08/09 856,000 08/09 166,000 09/10 947,000 09/10 167,000 television output (hours of origination) Source: BBC BBC Cymru Wales English language programmes BBC Cymru Wales on S4C 07/08 766 07/08 566 08/09 721 08/09 590 09/10 706 09/10 690 1 947,000 517,000 Average number of viewers to BBC Wales English Adults in Wales who listened to either BBC Radio language programming each week in 2009/10 Wales and/or Radio Cymru each week in 2009/10 (based on 15-minute reach). 6,470,000 66% the average UK audience on BBC one for each Percentage of adults in Wales with access episode of Torchwood: Children of Earth in July 2009. to broadband internet at home. Radio weekly reach (adults) Source: Rajar/ipsos MoRi BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Cymru 07/08 440,000 07/08 152,000 08/09 435,000 08/09 155,000 09/10 411,000 09/10 147,000 BBC Cymru Wales output for BBC tV networks (BRoAdCASt) Hours of origination Expenditure £M (under Ofcom definitions*) 07/08 107 07/08 29 08/09 101 08/09 25 09/10 134 09/10 39 Website Weekly Unique Users Please note: figures issued in 2008/09 annual review included global users. -

Summary Overview of BBC Cymru Wales' Performance 2005/2006

1 Owain Glyndwr:The ˆ Last Welsh Prince 2 Gwynfor:Yr Aelod Dros Gymru? 3 Radio Cymru:Taro’r Post from the Urdd Eisteddfod Summary Overview of BBC Cymru Wales’ Performance 2005/2006 2 The Broadcasting Council made the following considerable increase in unique users to its Welsh and A Renewed Partnership with S4C National Radio for All Wales assessment of BBC Cymru Wales’ performance against English language sites and the popularity of Objectives which were set by the Governors their content. Developing a strategic partnership with S4C, Build on the successes of Radio Cymru and Radio for 2005/2006. continuing to supply the channel with its most Wales, raising share and reach, broadening the age Council acknowledged the importance of the popular output. and geographical range of their audiences, engaging Delivering the Vision contribution of BBC One Wales and BBC Two Wales with them both on air and in their communities. to network and commended the way in which BBC The Draft Strategic Partnership Deed of Agreement Continue to develop the vision for BBC Cymru Cymru Wales programmes in all genres on BBC One between the BBC and S4C was submitted to Council Council commended the performance of Radio Cymru, Wales, delivering programmes and schedules which Wales had resonated with audiences, noting in in February. Council approved the draft document and welcoming the fact that its reach and share had meet the needs, tastes and expectations of local particular the strength of local comedy and drama. It expressed the hope that it would be accepted by the increased for the second year running, the share of audiences, on television, radio and online in also noted that Wales Today, while showing some S4C Authority. -

The Essentials

COMING SOON The Essentials New channel numbers Vanity Fair on Sky Movies 2 Now Sky is even Your cut-out-and-keep guide (channel 302) Entertainment 155 E! 264 DiscHome&H 408 Sky Spts News Kids 101 BBC1 157 Ftn 265 Disc H&H +1 410 Eurosport UK 601 Cartoon Netwrk 102 BBC2 159 OBE 267 Artsworld 411 Eurosport2 UK 602 Cartoon Nwk + easier to use! 103 ITV1 161 Biography 269 UKTV Br’t Ideas 413 Motors TV 603 Boomerang 104 Channel 4 / 163 Hollywood TV 271 Performance 415 At The Races 604 Nickelodeon S4C 165 Bonanza 273 Fashion TV 417 NASN 605 Nick Replay We’re improving the way your on-screen TV guide 105 five 169 UKTVG2+1 275 Majestic TV 419 Extreme Sports 606 Nicktoons works, making it simpler and smoother than ever. If the 106 Sky One 173 Open Access 2 277 LONDON TV 421 Chelsea TV 607 Trouble 107 Sky Two 179 FX 279 Real Estate TV 423 Golf Channel 608 Trouble Reload changes haven’t happened on your screen yet, don’t 108 Sky Three 180 FX+ 281 Wine TV 425 Channel 425 609 Jetix worry, they will very soon! Read all about them here 109 UKTV Gold 181 Information TV 283 Disc. T&L 427 TWC 110 UKTV Gold +1 183 Passion TV 285 Baby Channel 429 Setanta Sports1 111 UKTVG2 185 abc1 430 Setanta Sports2 112 LIVINGtv 187 Raj TV Movies 432 Racing UK 113 LIVINGtv +1 189 More4 +1 301 Sky Movies 1 434 Setanta Ireland 114 LIVINGtv2 193 Rapture TV 302 Sky Movies 2 436 Celtic TV Sky Guide changes 115 BBC THREE 195 propeller 303 Sky Movies 3 438 Rangers TV 116 BBC FOUR 971 BBC 1 Scotland 304 Sky Movies 4 440 Sport Nation 972 BBC 1 Wales 305 Sky Movies 5 480 Prem Plus -

LCD Digital Colour TV

000COV.fm Page 1 Friday, August 19, 2005 1:51 PM 2-629-164-14(1) LCD Digital Colour TV Operating Instructions Before operating the TV, please read the “Safety information” section of this manual. Retain this manual for future reference. KDL-V32A12U KDL-V40A12U KDL-V32A12U KDL-V40A12U 2-629-164-14(1) Printed in Spain © 2005 Sony Corporation KDL-V32/40A12U PANTONE 320 2-629-164-14(1) 01GB-KLV40XUK.book Page 2 Wednesday, August 31, 2005 4:42 PM NOTICE FOR Introduction Thank you for choosing this Sony product. Before operating the TV, please read this manual CUSTOMERS thoroughly and retain it for future reference. A moulded plug complying with BS1363 is fitted to this equipment for your safety and convenience. Trademark information Should the fuse in the plug supplied need to be replaced, a 13 • is a registered trademark of the DVB project. AMP fuse approved by ASTA or BSI to BS 1362 (i.e., • “PlayStation” is a trademark of Sony Computer marked with or ) must be used. Entertainment, Inc. When an alternative type of plug is used it should be fitted • TruSurround technology is used as a virtualizer for Dolby with a 13 AMP FUSE, otherwise the circuit should be Virtual Surround. protected by a 13 AMP FUSE at the distribution board. • TruSurround, SRS and symbol are trademarks of If the plug supplied with this equipment has a detachable fuse SRS Labs, Inc. cover, be sure to attach the fuse cover after you change the TruSurround technology is incorporated under license fuse. Never use the plug without the fuse cover. -

REPORT of a DIGITAL SWITCHOVER TECHNICAL TRIAL at FERRYSIDE and LLANSTEFFAN

REPORT of A DIGITAL SWITCHOVER TECHNICAL TRIAL AT FERRYSIDE AND LLANSTEFFAN July 2005 0 Digital Switchover Technical Trial Report Page Index 01 Executive Summary 03 1. Introduction 08 - Background 08 - Objectives 08 - Timeline 09 2. Planning the Trial 10 - Previous Projects 10 - Structure and Responsibilities 11 - Site Selection 12 - Domestic Equipment 13 - Consultation with the Community 13 - Regulatory Aspects 15 - Security Numbers/Receiver "Credits" 16 - Research 17 3. The Trial Community 18 - General Description 18 - Ferryside 19 - Llansteffan 20 - Coverage and Reception in the Trial Area 22 4. Services 24 - DTT Services 24 - Digital Satellite Option – ‘freesat from Sky’ 25 - Pay-TV 26 - BBC TWO Wales and BBC 2W 26 - Main and Relay Transmitters 27 5. Coverage and Transmission 28 - Analogue and DTT Coverage 28 - Site Works and Installation 29 - Frequencies, Services and Transmitter Powers 30 - Monitoring 31 - Transmission Issues 31 - Switchover 32 - Conclusion 32 6. Aerials and Connectivity 33 - Reception Problems 33 - Aerial Problems 33 - Connectivity Problems 35 - Summary 36 1 7. Digital Receivers and Recording 37 - Provision of Digital Equipment 37 - Selection of Product for the Trial 37 - Procurement and Local Retailer Support 40 - Additional Options 40 - Identifying Household Requirements 40 - Information and Distribution of Equipment 41 - After the Trial 42 8. Consumer and User Issues 43 - Attitudes to the Trial 43 - Services 44 - Demonstrating Equipment and Building Consumer Confidence 45 - Installation 45 - User Issues 46 - -

Annual Repor T and Accounts 2005/2006

BBC Annual Report and Accounts ReportAnnual and BBC 2005/2006 British Broadcasting Corporation Broadcasting House London W1A 1AA bbc.co.uk Annual Repor t and © BBC 2006 Accounts 2005/2006 Purpose, vision and values The BBC’s purpose is to enrich people’s lives with programmes and services that inform, educate and entertain The BBC’s vision is to be the most creative organisation in the world Values I Trust is the foundation of the BBC: we are independent, impartial and honest I Audiences are at the heart of everything we do I We take pride in delivering quality and value for money I Creativity is the lifeblood of our organisation I We respect each other and celebrate our diversity so that everyone can give their best I We are one BBC: great things happen when we work together Contents 2 Chairman’s statement 4 Director-General’s report 6 The BBC now and in the future 10 Board of Governors 12 Executive Board 14 Governors’ review of objectives 22 The BBC at a glance Governors’ review of services 24 Television 32 Radio 40 New Media 46 News 50 BBC World Service & Global News 54 Nations & Regions 58 Governors’ review of commercial activities 60 Being accountable and responsible 68 Performance against Statements of Programme Policy commitments 2005/2006 76 Compliance 92 Financial review 95 Financial statements 140 Broadcasting facts and figures 151 Getting in touch with the BBC 152 Other information BBC Annual Report and Accounts 2005/2006 1 Chairman’s statement This is the last annual report from the The main function of the Trust will be to BBC Board of Governors, which is to ensure that licence fee payers’ expectations be replaced under the new draft Royal of the BBC are fulfilled in terms of the Charter by the BBC Trust. -

Tuning and Editing Channels

Model No. TX-L42WT50B TX-L47WT50B TX-L55WT50B Operating Instructions LCD Television Thank you for purchasing this Panasonic product. Please read these instructions carefully before operating this product and retain them for future reference. The images shown in this manual are for illustrative purposes only. English UK and Ireland model TQB0E2282 Features Smart VIERA DLNA Digital smart life to create new and exciting TV DLNA is a standard that makes digital electronics experiences (Networking / Easy Operation / Picture easier and more convenient to use on a home network. Quality / Eco / Design). (p. 94) 3D technology VIERA Connect - Enjoy great web entertainment You can enjoy viewing 3D images on this TV by (p. 21, 89) wearing the 3D Eyewear. VIERA Connect allows you to access some specific VIERA Touch Pad Controller websites supported by Panasonic, and enjoy internet VIERA Touch Pad Controller is designed to operate the contents such as videos, games, EPG, communication TV conveniently and intuitively, especially on VIERA tools, etc. from VIERA Connect home screen. Connect or internet contents. Link up and control the connected equipment with freesat HD tuner built-in “Q-Link” and “VIERA Link” (p. 97) This TV has a built-in freesat HD tuner. freesat is a free Q-Link and VIERA Link provide easy recording digital TV service which broadcasts via satellite so you and playback, creation of a home theatre without can receive TV, radio, interactive TV, and HD TV with complicated settings, etc. crystal clear reception. VIERA TOOLS - Display special feature icons for DVB-T2 tuner built-in easy accessibility (p. 43) DVB-T2 is an advanced digital terrestrial system for Special features (such as VIERA Link and Media more efficient transmission.