Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Santos, Aleixo, D'horta, Portes.Indd

ISSN (impresso) 0103-5657 ISSN (on-line) 2178-7875 Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia Volume 19 Número 2 www.ararajuba.org.br/sbo/ararajuba/revbrasorn Junho 2011 Publicada pela Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia São Paulo - SP Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 19(2), 134-153 ARTIGO Junho de 2011 Avifauna of the Juruti Region, Pará, Brazil Marcos Pérsio Dantas Santos1, Alexandre Aleixo2, Fernando Mendonça d’Horta3 and Carlos Eduardo Bustamante Portes4 1. Universidade Federal do Pará. Instituto de Ciências Biológicas. Laboratório de Ecologia e Zoologia de Vertebrados. Rua Augusto Corrêa, 1, Guamá, CEP 66075‑110, Belém, PA, Brasil. E‑mail: [email protected] 2. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Coordenação de Zoologia. Caixa Postal 399, CEP 66040‑170, Belém, PA, Brasil. E‑mail: aleixo@museu‑goeldi.br 3. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Biologia. Rua do Matão, 277, Cidade Universitária, CEP 05508‑090, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. E‑mail: [email protected] 4. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Pós‑Graduação em Zoologia. Caixa Postal 399, CEP 66040‑170, Belém, PA, Brasil. E‑mail: [email protected] Recebido em 02/03/2011. Aceito em 18/05/2011. RESUMO: Avifauna da região do Juruti, Pará, Brasil. A região que compreende o interflúvio Madeira‑Tapajós é certamente uma das regiões brasileiras de maior complexidade ambiental e um dos mais importantes centros de endemismos de aves da América do Sul, denominado centro de endemismo Madeira ou Rondônia. Entretanto, essa região vem sofrendo um crescente aumento nas pressões antrópicas, principalmente pelo desmatamento, o que implica uma forte preocupação sobre a conservação de toda a biota dessa região. -

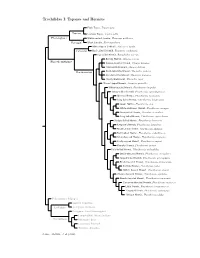

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Avian Communities in Temperate and Tropical Alder Forests

Condor, 80:2X-284 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1978 AVIAN COMMUNITIES IN TEMPERATE AND TROPICAL ALDER FORESTS EDMUND W. STILES Patterns of bird species richness have been Measures of niche breadth along these di- studied fairly extensively (Lack 1933, Gibb mensions were calculated using the Informa- 1954, MacArthur and MacArthur 1961, Dia- tion Theory Index of diversity (- 8 pi In pi). mond and Terborgh 1967, Terborgh 1967, Balda 1969, Orians 1969, Cody 1970, Karr and STUDY AREAS AND METHODS Roth 1971, Pearson 1971, 1975, 1977, Lovejoy I studied bird communities in mature forests of Red 1975). These patterns have been interpreted Alder (Alnus T&U) in Washington and A. ioruZZensis in terms of gradients of vegetation structural in Costa Rica. Forests of r&a occur at low to mid complexity, elevation, latitude, temporal pre- elevations from southern Alaska to central California dictability of resources and climatic severity. along the Pacific coast of North America. Forests of Some studies have dealt with temperate- jorullensis occur at mid-montane elevations in Cen- tral America and irregularly along the Andes as far tropical comparisons (MacArthur et al. 1966, south as northern Argentina. Terborgh and Weske 1969, Karr 1971, Cody Two plots of approximately 4 ha were each marked 1974), or with the concepts of latitudinal gra- in Washington and in Costa Rica. Trails were cut dients (Pianka 1966)) but no investigation has through the plots to facilitate observation. The Wash- ington study sites, (plots 4A and 4B in Stiles, in press; compared individual species ’ patterns of re- l-3 are early successional stages of A. -

A Comprehensive Multilocus Phylogeny of the Neotropical Cotingas

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 81 (2014) 120–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae, Aves) with a comparative evolutionary analysis of breeding system and plumage dimorphism and a revised phylogenetic classification ⇑ Jacob S. Berv 1, Richard O. Prum Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208105, New Haven, CT 06520, USA article info abstract Article history: The Neotropical cotingas (Cotingidae: Aves) are a group of passerine birds that are characterized by Received 18 April 2014 extreme diversity in morphology, ecology, breeding system, and behavior. Here, we present a compre- Revised 24 July 2014 hensive phylogeny of the Neotropical cotingas based on six nuclear and mitochondrial loci (7500 bp) Accepted 6 September 2014 for a sample of 61 cotinga species in all 25 genera, and 22 species of suboscine outgroups. Our taxon sam- Available online 16 September 2014 ple more than doubles the number of cotinga species studied in previous analyses, and allows us to test the monophyly of the cotingas as well as their intrageneric relationships with high resolution. We ana- Keywords: lyze our genetic data using a Bayesian species tree method, and concatenated Bayesian and maximum Phylogenetics likelihood methods, and present a highly supported phylogenetic hypothesis. We confirm the monophyly Bayesian inference Species-tree of the cotingas, and present the first phylogenetic evidence for the relationships of Phibalura flavirostris as Sexual selection the sister group to Ampelion and Doliornis, and the paraphyly of Lipaugus with respect to Tijuca. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Chinese Hwamei Garrulax Canorus

Complete mitochondrial genome of the Chinese Hwamei Garrulax canorus (Aves: Passeriformes): the first representative of the Leiothrichidae family with a duplicated control region D.S. Chen1*, C.J. Qian1*, Q.Q. Ren1,2, P. Wang1, J. Yuan1, L. Jiang1, D. Bi1, Q. Zhang1, Y. Wang1 and X.Z. Kan1,2 1Provincial Key Laboratory of the Conservation and Exploitation Research of Biological Resources in Anhui, College of Life Sciences, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, China 2The Institute of Bioinformatics, College of Life Sciences, Anhui Normal University, Wuhu, China *These authors contributed equally to this study. Corresponding author: X.Z. Kan E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (3): 8964-8976 (2015) Received January 11, 2015 Accepted May 8, 2015 Published August 7, 2015 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2015.August.7.5 ABSTRACT. The Chinese Hwamei Garrulax canorus, a member of the family Leiothrichidae, is commonly found in central and southern China, northern Indochina, and on Hainan Island. In this study, we sequenced the complete mitochondrial genome of G. canorus. The circular mitochondrial genome is 17,785 bp in length and includes 13 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and two ribosomal RNA genes. In addition, two copies of highly Genetics and Molecular Research 14 (3): 8964-8976 (2015) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br Mitogenome of Garrulax canorus 8965 similar putative control regions were observed in the mitochondrial genome. As found in other vertebrates, most of the genes are coded on the H-strand, except for one protein-coding gene (nad6; NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6) and eight tRNA genes (tRNAGln, tRNAAla, tRNAAsn, tRNACys, tRNATyr, tRNASer(UCN), tRNAPro, and tRNAGlu). -

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

![Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/downloaded-from-birdtree-org-48-to-take-into-account-phylogenetic-uncertainty-in-the-comparative-analyses-67-245125.webp)

Downloaded from Birdtree.Org [48] to Take Into Account Phylogenetic Uncertainty in the Comparative Analyses [67]

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Distribution of iridescent colours in Open Peer-Review hummingbird communities results Open Data from the interplay between Open Code selection for camouflage and communication Cite as: preprint Posted: 15th November 2019 Hugo Gruson1, Marianne Elias2, Juan L. Parra3, Christine Recommender: Sébastien Lavergne Andraud4, Serge Berthier5, Claire Doutrelant1, & Doris Reviewers: Gomez1,5 XXX Correspondence: 1 [email protected] CEFE, Univ Montpellier, CNRS, Univ Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, EPHE, IRD, Montpellier, France 2 ISYEB, CNRS, MNHN, Sorbonne Université, EPHE, 45 rue Buffon CP50, Paris, France 3 Grupo de Ecología y Evolución de Vertrebados, Instituto de Biología, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia 4 CRC, MNHN, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, CNRS, Paris, France 5 INSP, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Paris, France This article has been peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology 1 of 33 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/586362; this version posted November 19, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Identification errors between closely related, co-occurring, species may lead to misdirected social interactions such as costly interbreeding or misdirected aggression. This selects for divergence in traits involved in species identification among co-occurring species, resulting from character displacement. -

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-Eaters, Babblers, and a Whole Lot More

BORNEO: Bristleheads, Broadbills, Barbets, Bulbuls, Bee-eaters, Babblers, and a whole lot more A Tropical Birding Set Departure July 1-16, 2018 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Borneo lies in one of the biologically richest areas on Earth – the Asian equivalent of Costa Rica or Ecuador. It holds many widespread Asian birds, plus a diverse set of birds that are restricted to the Sunda region (southern Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo), and dozens of its own endemic birds and mammals. For family listing birders, the Bornean Bristlehead, which makes up its own family, and is endemic to the island, is the top target. For most other visitors, Orangutan, the only great ape found in Asia, is the creature that they most want to see. But those two species just hint at the wonders held by this mysterious island, which is rich in bulbuls, babblers, treeshrews, squirrels, kingfishers, hornbills, pittas, and much more. Although there has been rampant environmental destruction on Borneo, mainly due to the creation of oil palm plantations, there are still extensive forested areas left, and the Malaysian state of Sabah, at the northern end of the island, seems to be trying hard to preserve its biological heritage. Ecotourism is a big part of this conservation effort, and Sabah has developed an excellent tourist infrastructure, with comfortable lodges, efficient transport companies, many protected areas, and decent roads and airports. So with good infrastructure, and remarkable biological diversity, including many marquee species like Orangutan, several pittas and a whole Borneo: Bristleheads and Broadbills July 1-16, 2018 range of hornbills, Sabah stands out as one of the most attractive destinations on Earth for a travelling birder or naturalist. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys.