Male-Plumaged Anna's Hummingbird Feeds Chicks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

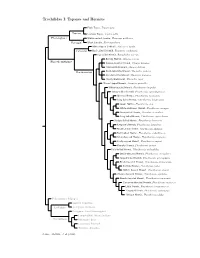

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

The Behavior and Ecology of Hermit Hummingbirds in the Kanaku Mountains, Guyana

THE BEHAVIOR AND ECOLOGY OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS IN THE KANAKU MOUNTAINS, GUYANA. BARBARA K. SNOW OR nearly three months, 17 January to 5 April 1970, my husband and I F camped at the foot of the Kanaku Mountains in southern Guyana. Our camp was situated just inside the forest beside Karusu Creek, a tributary of Moco Moco Creek, at approximately 80 m above sea level. The period of our visit was the end of the main dry season which in this part of Guyana lasts approximately from September or October to April or May. Although we were both mainly occupied with other observations we hoped to accumulate as much information as possible on the hermit hummingbirds of the area, particularly their feeding niches, nesting and social organization. Previously, while living in Trinidad, we had studied various aspects of the behavior and biology of the three hermit hummingbirds resident there: the breeding season (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1964)) the behavior at singing assemblies of the Little Hermit (Phaethornis Zonguemareus) (D. W. Snow, 1968)) the feeding niches (B. K. Snow and D. W. Snow, 1972)) the social organization of the Hairy Hermit (Glaucis hirsuta) (B. K. Snow, 1973) and its breeding biology (D. W. Snow and B. K. Snow, 1973)) and the be- havior and breeding of the Guys’ Hermit (Phuethornis guy) (B. K. Snow, in press). A total of six hermit hummingbirds were seen in the Karusu Creek study area. Two species, Phuethornis uugusti and Phaethornis longuemureus, were extremely scarce. P. uugusti was seen feeding once, and what was presumably the same individual was trapped shortly afterwards. -

The Band-Tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes Ruckeri (Trochilidae), in Guatemala

286 GeneralNotes [ Vol.Auk 82 1942) doesnot list the frog as a predator upon phoebes.Instances of frogs capturing other small birds have been recorded, however. A frog of unidentified specieswas seen to capture an adult Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorusru/us) (M. Monroe, Condor, 59: 69, 1957). A bullfrog was observedto capture and eat an adult Brown Towhee (Pipilo/uscus) (W. Howard, Copeia, 1950: 152). C. R. S. Pitman (Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl., 77: 125, 1957), writing about the aquaticpredators of birds, stated: "Large speciesof Rana, suchas R. adspersaand R. occipitalis,are voraciousand will take any suitable living thing which comestheir way." Horizontal surfacesof bridges over water are common nesting sites for phoebes. It is possible that the above-describedfate is a not infrequent one for young phoebes leavingthe nest. Although the incidentindicates that young phoebesare instinctively able to swim, and would consequentlyusually not drown, yet they may often fall prey to frogs if their first flight ends in water.--T•) R. AN•)•RSON,7803 Summit, Kansas City, Missouri. The Band-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes ruekeri (Trochilidae), in Guatemala. --In a letter published in The Ibis in 1873 (p. 428) Osbert Salvin reported seeing a specimenof Threnetes ruckeri in a collection of birds kept by the SociedadEconomica de Guatemala. On the strengthof this statementthe country was includedin the range of the speciesin several subsequentworks, notably: Salvin, Catalogue o] the Picariae in the collection o/ the British Museum, Upupae and Trochili, 1892 (vol. 16, Cat. o] the birds in the British Museum), p. 265; Salvin and Godman, Biologla Centrali- Americana,Aves, vol. 2, 1888-97, p. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Use of Floral Nectar in Heliconia Stilesii Daniels by Three Species of Hermit Hummingbirds

The Condor89~779-787 0 The Cooper OrnithologicalSociety 1987 ECOLOGICAL FITTING: USE OF FLORAL NECTAR IN HELICONIA STILESII DANIELS BY THREE SPECIES OF HERMIT HUMMINGBIRDS FRANK B. GILL The Academyof Natural Sciences,Philadelphia, PA 19103 Abstract. Three speciesof hermit hummingbirds-a specialist(Eutoxeres aquikz), a gen- eralist (Phaethornissuperciliosus), and a thief (Threnetesruckerz]-visited the nectar-rich flowers of Heliconia stilesii Daniels at a lowland study site on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica. Unlike H. pogonanthaCufodontis, a related Caribbean lowland specieswith a less specialized flower, H. stilesii may not realize its full reproductive potential at this site, becauseit cannot retain the services of alternative pollinators such as Phaethornis.The flowers of H. stilesii appear adapted for pollination by Eutoxeres, but this hummingbird rarely visited them at this site. Lek male Phaethornisvisited the flowers frequently in late May and early June, but then abandonedthis nectar sourcein favor of other flowers offering more accessiblenectar. The strong curvature of the perianth prevents accessby Phaethornis to the main nectar chamber; instead they obtain only small amounts of nectar that leaks anteriorly into the belly of the flower. Key words: Hummingbird; pollination; mutualism;foraging; Heliconia stilesii; nectar. INTRODUCTION Ultimately affectedare the hummingbird’s choice Species that expand their distribution following of flowers and patterns of competition among speciationenter novel ecologicalassociations un- hummingbird species for nectar (Stiles 1975, related to previous evolutionary history and face 1978; Wolf et al. 1976; Feinsinger 1978; Gill the challenges of adjustment to new settings, 1978). Use of specificHeliconia flowers as sources called “ecological fitting” (Janzen 1985a). In the of nectar by particular species of hermit hum- case of mutualistic species, such as plants and mingbirds, however, varies seasonally and geo- their pollinators, new ecological settingsmay in- graphically (Stiles 1975). -

Fundación Jocotoco Narupa Reserve Bird Checklist

FUNDACIÓN JOCOTOCO NARUPA RESERVE BIRD CHECKLIST N° English Name Latin Name Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 1 Gray Tinamou Tinamus tao 2 Great Tinamou Tinamus major 3 Brown Tinamou Crypturellus obsoletus 4 Black Tinamou Tinamus osgoodi 5 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui 6 Torrent Duck Merganetta armata 7 Spix's Guan Penelope jacquacu 8 Wattled Guan Aburria aburri 9 Sickle-winged Guan Chamaepetes goudotii 10 Rufous-breasted Wood-Quail Odontophorus speciosus 11 Fasciated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma fasciatum 12 King Vulture Sarcoramphus papa 13 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 14 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura 15 Greater Yellow-headed Vulture Cathartes melambrotus 16 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 17 Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus 18 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 19 Semicollared Hawk Accipiter collaris 20 Tiny Hawk Accipiter superciliosus 21 Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps 22 Harpy Eagle Harpia harpyja 23 Solitary eagle Buteogallus solitarius 24 Roadside Hawk Rupornis magnirostris 25 Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus 26 Swainson's Hawk Buteo swainsoni 27 Black Hawk- Eagle Spizaetus tyrannus 28 Black-and-chestnut Eagle Spizaetus isidori 29 Chestnut-headed Crake Anurolimnas castaneiceps 30 Blackish Rail Pardirallus nigricans 31 Sunbittern Eurypyga helias 32 Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius 33 Least Sandpiper Calidris minutilla 34 Scaled Pigeon Patagioenas speciosa 35 Ruddy Pigeon Patagioenas subvinacea 36 Plumbeous Pigeon Patagioenas plumbea 37 Gray-fronted Dove Leptotila rufaxilla 38 White-tipped Dove Leptotila verreauxi 39 Sapphire -

WB-V42(4)-Webcomp.Pdf

Volume 42, Number 4, 2011 Arizona Bird Committee Report, 2005–2009 Records Gary H. Rosenberg, Kurt Radamaker, and Mark M. Stevenson ..............198 Mitochondrial DNA and Meteorological Data Suggest a Caribbean Origin for New Mexico’s First Sooty Tern Andrew B. Johnson, Sabrina M. McNew, Matthew S. Graus, and Christopher C. Witt .............................233 NOTES Northerly Extension of the Breeding Range of the Roseate Spoonbill in Sonora, Mexico Abram B. Fleishman and Naomi S. Blinick ......243 Male-Plumaged Anna’s Hummingbird Feeds Chicks Elizabeth A. Mohr ...................................................................247 Severe Bill Deformity of an American Kestrel Wintering in California William M. Iko and Robert J. Dusek ......................251 Book Review Mike McDonald ...................................................255 Featured Photo: First Evidence for Eccentric Prealternate Molt in the Indigo Bunting: Possible Implications for Adaptive Molt Strategies Jared Wolfe and Peter Pyle ...................................257 Index Daniel D. Gibson .............................................................263 Front cover photo by © Charles W. Melton of Hereford, Arizona: Fan-tailed Warbler (Euthlypis lachrymosa), Madera Canyon, Santa Cruz County, Arizona, 24 May 2011. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Peter Pyle of Point Reyes Sta- tion, California: Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) more than one year old, captured 18 April 2011 in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, following eccentric prealternate molt (top); Indigo Bunting more -

Bfree Bird List

The following is a list of species of birds that have been recorded in the vicinity of BFREE, a scientific field station in Toledo District, southern Belize. The list includes birds seen on the 1,153 private reserve and in the adjacent protected area, the Bladen Nature Reserve. BFREE BIRD LIST ❏ Neotropic ❏ Double-toothed ❏ Little Tinamou Cormorant Kite ❏ Thicket Tinamou ❏ Anhinga ❏ White Tailed Kite ❏ Slaty-breasted ❏ Brown Pelican ❏ Plumbeous Kite Tinamou ❏ Bare-throated ❏ Black-collared ❏ Plain Chachalaca Tiger-Heron Hawk ❏ Crested Guan ❏ Great Blue Heron ❏ Bicolored Hawk ❏ Great Curassow ❏ Snowy Egret ❏ Crane Hawk ❏ Ocellated Turkey ❏ Little Blue Heron ❏ White Hawk ❏ Spotted ❏ Cattle Egret ❏ Gray Hawk Wood-Quail ❏ Great Egret ❏ Sharp-shinned ❏ Singing Quail ❏ Green Heron Hawk ❏ Black-throated ❏ Agami Heron ❏ Common Bobwhite ❏ Yellow-crowned Black-Hawk ❏ Ruddy Crake Night-Heron ❏ Great Black-Hawk ❏ Gray-necked ❏ Boat-billed Heron ❏ Solitary Eagle Wood-Rail ❏ Wood Stork ❏ Roadside Hawk ❏ Sora ❏ Jabiru Stork ❏ Zone-tailed Hawk ❏ Sungrebe ❏ Limpkin ❏ Crested Eagle ❏ Killdeer ❏ Black-bellied ❏ Harpy Eagle ❏ Northern Jacana Whistling-Duck ❏ Black-and-white ❏ Solitary Sandpiper ❏ Muscovy Duck Hawk-Eagle ❏ Lesser Yellow Legs ❏ Blue-winged Teal ❏ Black Hawk-Eagle ❏ Spotted Sandpiper ❏ Black Vulture ❏ Ornate Hawk-Eagle ❏ Pale-vented Pigeon ❏ Turkey Vulture ❏ Barred ❏ Short-billed Pigeon ❏ King Vulture Forest-Falcon ❏ Scaled Pigeon ❏ Lesser ❏ Collared ❏ Ruddy Yellow-headed Forest-Falcon Ground-Dove Vulture ❏ Laughing Falcon ❏ Blue Ground-Dove -

The Hummingbirds of Nariño, Colombia

The hummingbirds of Nariño, Colombia Paul G. W. Salaman and Luis A. Mazariegos H. El departamento de Nariño en el sur de Colombia expande seis Areas de Aves Endemicas y contiene una extraordinaria concentración de zonas de vida. En años recientes, el 10% de la avifauna mundial ha sido registrada en Nariño (similar al tamaño de Belgica) aunque ha recibido poca atención ornitólogica. Ninguna familia ejemplifica más la diversidad Narinense como los colibríes, con 100 especies registradas en siete sitios de fácil acceso en Nariño y zonas adyacentes del Putumayo. Cinco nuevas especies de colibríes para Colombia son presentadas (Campylopterus villaviscensio, Heliangelus strophianus, Oreotrochilus chimborazo, Patagona gigas, y Acestrura bombus), junto con notas de especies pobremente conocidas y varias extensiones de rango. Una estabilidad regional y buena infraestructura vial hacen de Nariño un “El Dorado” para observadores de aves y ornitólogos. Introduction Colombia’s southern Department of Nariño covers c.33,270 km2 (similar in size to Belgium or one quarter the size of New York state) from the Pacific coast to lowland Amazonia and spans the Nudo de los Pastos massif at 4,760 m5. Six Endemic Bird Areas (EBAs 39–44)9 and a diverse range of life zones, from arid tropical forest to the wettest forests in the world, are easily accessible. Several researchers, student expeditions and birders have visited Nariño and adjacent areas of Putumayo since 1991, making several notable ornithological discoveries including a new species—Chocó Vireo Vireo masteri6—and the rediscovery of several others, e.g. Plumbeous Forest-falcon Micrastur plumbeus, Banded Ground-cuckoo Neomorphus radiolosus and Tumaco Seedeater Sporophila insulata7.