Al-Mawasi, Gaza Strip Impossible Life in an Isolated Enclave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Practices of Irrigation Water Pricing

\J4S ILI(QQ POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Public Disclosure Authorized Efficiency and Equity Pricing of water may affect allocation considerations by Considerations in Pricing users. Efficiency isattainable andAllocating Irrigation wheneverthe pricing method affectsthe demandfor Public Disclosure Authorized Water irrigation water. The extent to which water pricing methods can affect income Yacov Tsur redistributionis limited.To Ariel Dinar affect incomeinequality, a water pricing method must include certain forms of water quantity restrictions. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The WorldBank Agricultureand Natural ResourcesDepartment Agricultural Policies Division May 1995 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Summary findings Economic efficiency has to do with how much wealth a inefficient allocation. But they are usually easier to given resource base can generate. Equity has to do with implement and administer and require less information. how that wealth is to be distributed in society. Economic The extent to which water pricing methods can effect efficiency gets far more attention, in part because equity income redistribution is limited, the authors conclude. considerations involve value judgments that vary from Disparities in farm income are mainly the result of person to person. factors such as farm size and location and soil quality, Tsur and Dinar examine both the efficiency and the but not water (or other input) prices. Pricing schemes equity of different methods of pricing irrigation water. that do not involve quantity quotas cannot be used in After describing water pricing practices in a number of policies aimed at affecting income inequality. countries, they evaluate their efficiency and equity. The results somewhat support the view that water In general they find that water use is most efficient prices should not be used to effect income redistribution when pricing affects the demand for water. -

The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and Their Impact on Israeli-Palestinian Peace Efforts

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-25-2018 The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli-Palestinian Peace Efforts Daniel Bucksbaum Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Bucksbaum, Daniel, "The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli- Palestinian Peace Efforts" (2018). Honors Theses. 3009. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/3009 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Changing Geopolitical Dynamics of the Middle East and their Impact on Israeli- Palestinian Peace Efforts By Daniel Bucksbaum A thesis submitted to the Lee Honors College Western Michigan University April 2018 Thesis Committee: Jim Butterfield, Ph.D., Chair Yuan-Kang Wang, Ph.D. Mustafa Mughazy, Ph.D. Bucksbaum 1 Table of Contents I. Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 II. Source Material……………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 III. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 IV. Historical Context for the Two-State Solution………………………………………………………...6 a. Deeply Rooted and Ideological Claims to the Land……………………………………………….…..7 b. Legacy of the Oslo Accords……………………………………………………………………………………….9 c. Israeli Narrative: Why the Two-State Solution is Unfeasible……………………………………19 d. Palestinian Narrative: Why the Two-State Solution has become unattainable………..22 e. Drop in Support for the Two-State Solution; Negotiations entirely…………………………27 f. -

The Absentee Property Law and Its Implementation in East Jerusalem a Legal Guide and Analysis

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL The Absentee Property Law and its Implementation in East Jerusalem A Legal Guide and Analysis May 2013 May 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Consulting legal advisor: Adv. Sami Ershied Language editor: Risa Zoll Hebrew-English translations: Al-Kilani Legal Translation, Training & Management Co. Cover photo: The Cliff Hotel, which was declared “absentee property”, and its owner Ali Ayad. (Photo by: Mohammad Haddad, 2013). This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Talia Sasson, Adv. Daniel Seidmann and Adv. Raphael Shilhav for their insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 2. Background on the Absentee Property Law .................................................. 9 3. Provisions of the Absentee Property Law .................................................... 14 3.1 Definitions .................................................................................................................... -

500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES

500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES SYNOPSIS 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N is a documentary about the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd which was captured and depopulated by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and subsequently transformed into a Jewish artist's colony and renamed Ein Hod. It tells the story of the village's original inhabitants who, after expulsion, settled only 1.5 kilometers away in the outlying hills. Since Israeli law prevents Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, the refugees of Ayn Hawd established a new village: “Ayn Hawd al-Jadida” (The New Ayn Hawd). Ayn Hawd al-Jadida is an unrecognized village, which means that it receives no services such as electricity, water, or an access road. Relations between the artists and the refugees are complex: unlike most Israelis, the residents of Ein Hod know the Palestinians who lived there before them, since the latter have worked as hired hands for the former. Unlike most Palestinian refugees, the residents of Ayn Hawd al-Jadida know the Israelis who now occupy their homes, the art they produce, and the peculiar ways they try to deal with the fact that their society was created upon the ruins of another. It echoes the story of indigenous peoples everywhere: oppression, resistance, and the struggle to negotiate the scars of the past with the needs of the present and the hopes for the future. Addressing the universal issues of colonization, landlessness, housing rights, gentrification, and cultural appropriation in the specific context of Israel/Palestine, 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N documents the art of dispossession and the creativity of the dispossessed. -

Land Dispossession and Its Impact on Agriculture Sector and Food Sovereignty in Palestine: a New Perspective on Land Day

Land dispossession and its impact on agriculture sector and food sovereignty in Palestine: a new perspective on Land Day Inès Abdel Razek-Faoder and Muna Dajani On 30 March 1976, 37 years ago, in response to the Israeli government's announcement of a plan to expropriate thousands of dunams1 of land for "security and settlement purposes" on the lands of Galilee villages of Sakhnin and Arraba, Dair Hanna, Arab Alsawaed and other areas thousands of people took the street to protest, calling for a general strike as a peaceful mean to resisting colonization and government plans of judaization of the Galilee. Six Palestinians in Israel were killed. A month later the Koenig2 Memorandum was leaked to the press recommending, for “national interest”, “the possibility of diluting existing Arab population concentrations”. Land Day has been since then commemorated in all Palestine as a day of steadfastness and resistance. It became a symbol of the refusal of the Palestinians to leave their homeland, and to reject any form of ethnic cleansing and pressures for displacement. It is a day of attachment to freedom, on both sides of the Green Line and in all corners of the world. On this occasion, 37 years later, there is a necessity to highlight the consequences of this systematic illegal dispossession and control over the land and its natural resources on farming and agriculture. Farming has been fundamental in Palestinian identity and history, deeply rooted in the culture of land and of the struggle for freedom since the beginning of the 20th century. Predominantly an agricultural community, Palestine has been transformed from depending on its systems of self-sufficiency farming to the industrial chemical agriculture of today, all this under a brutal occupation depriving farmers of their land and water resources. -

Despite Pandemic, Israeli Forces Drop Herbicide on Gaza and Shoot at Fishermen

Despite pandemic, Israeli forces drop herbicide on Gaza and shoot at fishermen NewsKate on April 11, 2020 0 Comments Gaza fish market. (Photo: Mohammed Assad) Gaza PCHR: In new Israeli violation, Israeli naval forces wound 2 fishermen in northern Gaza sea BEIT LAHIA 9 Apr — Israeli naval forces continue their attacks against Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Sea preventing them from sailing and fishing freely, accessing the zones rich in fish, despite the fact that fishermen posed no threat to the lives of Israeli naval forces deployed in Gaza waters … According to the investigations of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights (PCHR), at approximately 07:50 on Thursday, 09 April 2020, Israeli gunboats stationed northwest of Beit Lahia in northern Gaza Strip chased Palestinian fishing boats sailing within the allowed fishing area (3 nautical miles) and opened fire at a fishing boat. As a result, two fishermen, Obai ‘Adel Mohamed Jarbou‘ (21) and Ahmed ‘Abed al-Fattah Ahmed al-Sharfi (23), were shot and injured with rubber-coated steel bullets. The young men, from al-Shati’ [‘Beach’] camp in Gaza City, were taken to the Indonesian Hospital, where their injuries were classified as minor. It should be noted that Israeli gunboats conduct daily chases of Palestinian fishermen in the Gaza Strip, and open fire at them in order to terrify them and prevent them from sailing and accessing the zones rich in fish. The latest Israeli naval forces’ attack was on Wednesday, 08 April 2020, as Israeli gunboats stationed northwest of Beit Lahia in northern Gaza Strip, chased Palestinian fishing boats sailing within the allowed fishing area (3 nautical miles) and opened fire at a fishing boat. -

Statistical Handbook of Middle Eastern Countries, Palestine, Cyprus, Egypt

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/statisticalhandbOOjewi JEWISH AGENCY FOR PAI^ESTINE ECONOMIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE STATISTICAL HANDBOOK OF MIDDLE EASTERN COUNTRIES PALESTINE, CYPRUS, EGYPT, IRAQ, THE LEBANON, SYRIA, TRANSJORDAN, TURKEY JERUSALEM, 1945 DISTRIBUTOR: D. B. AARONSON, P. O. B. 1175, JERUSALEM FOREWORD TO SECOND EDITION. This Handbook went out of print shortly after its first appearance, and a second edition was decided upon in response to numerous requests. In addition to the correction of certain misprints, the present issue includes an outline table as well as a supplement contaming new figures which have meanwhile become available. These additional statistics have been given the same serial numbers as the corresponding tables in the main text. The footnote signs are likewise those of the main tables. Suggestions for improvements or amendments to be included in any later edition will be appreciated. Jerusalem, April 1945. A. B. Copyright 1 944 by ihe Economic Research Institute of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, Jerusalem. Reprinted (with additions), 1945. Printed in Palestine by Stereotypes at tbe Azriel Printing Works, Jerusalem. -' PREFACE. -5 Modern economic policy has become almost entirely dependent on re- liable information regarding the processes and tendencies of economic and social life, which has been reduced to numerical statements and relationships. The growing complexity of modern society, the close connections to be found between the priyate and public fields of economy, the degree to which Government finance is dependent on foreign trade, employment, price level and other indices of economic development — all these make it necessary for the figures and data of economic and social life to be constantly available if state and political activities are to be successfully conducted nowadays. -

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY on WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT and AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION in the REPUBLIC of IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 the REPUBLIC of IRAQ

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 REPORT IRAQ FINAL THE REPUBLIC OF IN IRRIGATION AGRICULTURE AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT WATER ON COLLECTION SURVEY DATA THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) NTC International Co., Ltd. 7R JR 16-008 英文 118331.402802.28.4.14 作業;藤川 Directorate Map Dohuk N Albil Nineveh Kiekuk As-Sulaymaniyyah Salah ad-Din Tigris river Euphrates river Bagdad Diyala Al-Anbar Babil Wasit Karbala Misan Al-Qadisiyan Al-Najaf Dhi Qar Al-Basrah Al-Muthanna Legend Irrigation Area International boundary Governorate boundary River Location Map of Irrigation Areas ( ii ) Photographs Kick-off meeting with MoWR officials at the conference Explanation to D.G. Directorate of Legal and Contracts of room of MoWR MoWR on the project formulation (Conference room at Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. MoWR) Kick-off meeting with MoA officials at the office of MoA Meeting with MoP at office of D.G. Planning Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. Both parties discussed about project formulation Courtesy call to the Minister of MoA Meeting with representatives of WUA assisted by the JICA JICA side explained the progress of the irrigation sector loan technical cooperation project Phase 1. and further project formulation process. (Conference room of MoWR) ( iii ) Office of AL-Zaidiya WUA AL-Zaidiya WUA office Site field work to investigate WUA activities during the JICA team conducted hearing investigation on water second field survey (Dhi-Qar District) management, farming practice of WUA (Dhi-Qar District) Piet Ghzayel WUA Piet Ghzayel WUA Photo shows the eastern portion of the farmland. -

Study on Small-Scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final

Study on Small-scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final Report Jacques Marzin. Cirad ART-Dév Ahmad Uwaidat. MARKAZ-Co Jean Michel Sourrisseau. CIRAD ART-Dév Submitted to: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) June 2019 ACRONYMS ACAD Arab Center for Agricultural Development CIRAD Centre International de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GDP Gross National Product LSS Livestock Sector Strategy MoA Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture NASS National Agricultural Sector Strategy NGO Non-governmental organization PACI Palestinian Agricultural Credit Institution PCBS Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics PNAES Palestinian National Agricultural Extension Strategy PARPIF Palestinian Agricultural Risk Prevention and Insurance Fund SDGs Sustainable Development Goals (UN) SSFF Small-scale family farming UNHRC United Nations human rights council WFP World Food Programme 1 CONTENTS General introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and objectives of the study ...................................................................................................................... 5 Empirical material for this study ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgement and disclaimer .................................................................................................................... -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

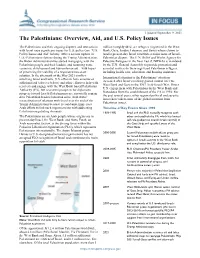

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

Rantis Village Profile

Rantis Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate.