A Quick Assessment Tool for Humandirected Aggression in Pet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

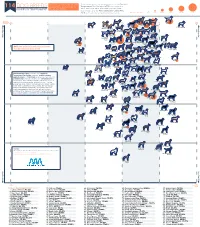

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups 5

Temperament assessment related to breed groups S.E. Dowd 2006 Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups Scot E. Dowd Ph.D. Matrix Canine Research Institute. PO BOX 1332, Shallowater, TX 79363, [email protected] , http://www.canineresearch.org . Abstract Breed specific legislations (BSL), are laws that discriminate against dogs of specific breeds and breed groups. BSL similar to human racial profiling is based upon the premise that certain breed types are more dangerous to humans because of genetic temperament predispositions. The American Pit Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier are the breeds most targeted by BSL. In the current study, the temperaments of over 25,000 dogs, of various breeds, have been evaluated including 1136 dogs from the pit bull group and 469 American Pit Bull Terriers. Using results of a rigorous pass-fail temperament test, designed to evaluate characteristics such as human aggression, these analyses statistically evaluated the proportion of dogs categorized by breed groups (e.g. sporting, pit bull, hound, toy, terrier) passing. Interestingly, results show that the pit bull group had a significantly higher passing proportion (p < 0.05) than all other pure breed groups, except the Sporting and Terrier groups. These groups however, did not have a statistically higher passing proportion (p = 0.78) than the pit bull group. This study has provided data to indicate the classification of dog breed groups with respect to their inherent temperament, as part of BSL, may lack scientific credibility. Breed stereotyping, like racial profiling, ignores the complex environmental factors that contribute to canine temperament and behavior. -

Investigating the Effects of Incremental Conditioning

EXPLORING THE EFFECTS OF REPETITIVE ENDURANCE EXERCISE AND TRYPTOPHAN SUPPLEMENTATION OR DIETARY SOLUBLE FIBER ON THE BEHAVIOUR OF SLED DOGS by Eve Robinson A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Animal Biosciences Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Eve Robinson, August 2020 ABSTRACT EXPLORING THE EFFECTS OF REPETITIVE ENDURANCE EXERCISE AND TRYPTOPHAN SUPPLEMENTATION OR DIETARY SOLUBLE FIBER ON THE BEHAVIOUR OF SLED DOGS Eve Robinson Advisor: University of Guelph, 2020 Dr. Anna-Kate Shoveller The impacts of repetitive endurance exercise and dietary interventions on the behaviour and voluntary physical activity of dogs has not been previously studied. This thesis investigated the effects of incremental conditioning, supplemental tryptophan and increased dietary soluble fiber on the behaviour and voluntary physical activity of sled dogs. Repetitive endurance exercise generally resulted in a progressive decrease in voluntary physical activity and locomotive behaviours prior to an exercise bout. Additionally, voluntary physical activity increased after two consecutive rest days, indicating a potential recovery from the physiological impacts of endurance exercise. Increasing the tryptophan: large neutral amino acid ratio of the diet reduced agonistic behaviors prior to exercise, however, increasing the soluble fiber content had no effect on any behaviour prior to or following an exercise bout. This research could be used to improve the exercise training regimens and diets of sled dogs and promote their overall performance, health and well-being. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Anna-Kate Shoveller for providing me with this opportunity. I would not be where I am today without your support, encouragement, and confidence in me. -

Wgsdpa Bh Written Examination for Firt-Time Handlers

WGSDPA BH WRITTEN EXAMINATION FOR FIRT-TIME HANDLERS 1. The length of the leash that must be useD for the BH is: 33 Feet 3 Feet 6 Feet 2. The BH is an optional test anD the hanDler can opt to go right for the IGP 1: True False 3. The Traffic Portion of the BH is: Optional To Determine Acceptable Temperament Only requireD if you live in a metropolitan city Necessary to ensure the Dog has suitable temperament 4. For the long Down: The hanDler Disappears into a blinD The hanDler faces the Dog anD can eye signal the Dog to stay The handler’s back is to the Dog 5. The entire BH test is on leash True False 6. You can attempt the BH on Day 1 of the trial anD if you pass, attempt the IGP 1 on Day 2 True False 7. You can go right from BH to IGP FH WGSDPA BH WRITTEN EXAMINATION FOR FIRT-TIME HANDLERS No Yes It DepenDs on who you ask Thank you for taking this eXam. Begleithundprüfung (BH) EXAMINATION Host Club Name: Date: Name of Dog: Catalog #: Reg #: Tattoo/Chip: Birth Date: Handler Name: Breed: Result of the temperament test Pass/Fail A - BH Trial on Training Grounds or other open area Points Note 1 (On-lead heeling) 15 2 (Off-lead heeling) 15 3 (Sit exercise) 10 4 (Down with recall) 10 5 (Down under distraction) 10 (Total) 60 B - (Evaluation in traffic) 1 (Encounter with a group of people) 2 (Encounter with bicycle riders) 3 (Encounter with cars) 4 (Encounter with joggers and rollerbladers) 5 (Encounter with other dogs) 6 (Behavior of a dog that is tied up and left alone) EVALUATION Pass Fail WGSDPA JUDGES SHEET - IGP-1 Host Club Name: WGSDPA Date: Name of Dog: Catalog #: Reg #: Tattoo/Chip: Birth Date: Handler Name: Breed: TEMPERAMENT TEST: Pass or Fail? Pass or Fail? A -TRACKING PHASE A ) Tracklayer Name Time Track Laid ____Time Track Run__________________ ) Articles Indicated? Handler laid track of at least 300 paces long and aged 20 min. -

Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test (APET)—Revised 5/2015

Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test (APET)—Revised 5/2015 Avidog® Puppy Evaluation Test Helping Breeders Make the Best Match for Puppies and Owners Revised May 2015 Avidog® International, LLC www.Avidog.com Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Why Another Temperament Test? ...................................................................................................................... 4 A Little about the APET ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Who and What You Need for an APET ............................................................................................................... 10 When to Test ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 People and Roles ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Time ........................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Plan the Pups’ Meals .............................................................................................................................................. -

BOARD of DIRECTORS August 7-8, 2017 the Board Convened On

BOARD OF DIRECTORS August 7-8, 2017 The Board convened on Monday, August 7, 2017 at 8:00 a.m. All Directors were present. Also present was the Executive Secretary. The July 2017 Board minutes, copies of which were provided to all Directors, were discussed. Upon a motion by Dr. Davies, seconded by Mr. Menaker, the July 2017 minutes were approved unanimously, except for an abstention by Mr. Feeney because he was not in attendance at the July meeting. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Board Action Items Mr. Sprung reviewed Action Items, and reported on staff initiatives. There was discussion by the Board concerning reporting of efforts to increase registrations, entries and breeders as well as focus by staff to convert registerable dogs to registered dogs. There was debate about the impact of limited registration. It was the sense of the Board that limited registration was negatively impacting entries and registration totals. There was a motion by Mr. Wooding, seconded by Dr. Davies, and it was VOTED (unanimously), to instruct the Executive Secretary to send a memo to the Delegate Dog Show Rules Committee asking them to consider a rule change that would eliminate limited registration. Mr. Sprung agreed that the staff can provide parent clubs with statistics on litter, dog and limited registration for their respective breed. Fundraising Department Mr. Sprung introduced Robert Holcomb, AKC’s new Executive Director of Development. Mr. Holcomb gave an overview of his background in fundraising and his vision for how the new department would operate. Giving initiatives will be planned for all of AKC’s affiliates, which include, AKC Canine Health Foundation, AKC Reunite, AKC Humane Fund and the AKC Museum of the Dog as well as AKC. -

Understanding Canine Resource Guarding Behaviour: an Epidemiological Approach

Understanding Canine Resource Guarding Behaviour: An Epidemiological Approach by Jacquelyn Jacobs A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Population Medicine Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Jacquelyn Jacobs, April 2016 ABSTRACT Understanding Canine Resource Guarding Behaviour: A Qualitative and Quantitative Approach Jacquelyn Jacobs Advisors: University of Guelph, 2016 Dr. Lee Niel Dr. Jason B. Coe The overarching goal of this thesis was to improve the understanding of canine resource guarding (RG), which is defined as the use of avoidance, threatening, or aggressive behaviours to retain control of items in the presence of a person or other animal. Results from the first study, an online discussion board involving fourteen companion animal behaviour experts, identified most participants prefer to describe the behaviour as "resource guarding" due to the positive perception and interpretation of the term by dog owners, and the potential for inclusion of non- aggressive behaviour patterns such as avoidance and rapid ingestion. The second study examined dog owners‟ (n = 1438) ability to identify three different forms of resource guarding (i.e., avoidance, rapid ingestion or aggression). The non-aggressive patterns of RG, and those involving threatening aggression (e.g., growling, teeth baring) were significantly more difficult for participants to identify compared to biting aggression. Findings were used to develop a RG identification tool to ensure owners were able to correctly classify different types of RG in subsequent studies. For the third and fourth studies, dog owners were recruited (n = 3068) to complete a survey to determine factors associated with the expression of RG in the presence of either people or other dogs, respectively. -

Behavioural Differences in Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis Suggest Stress

animals Article Behavioural Differences in Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis Suggest Stress Could Be a Significant Problem Associated with Chronic Pruritus Naomi D. Harvey 1,* , Peter J. Craigon 1, Stephen C. Shaw 1,2, Sarah C. Blott 1 and Gary C.W. England 1 1 School of Veterinary Medicine and Science, The University of Nottingham, Leicestershire LE12 5RD, UK; [email protected] (P.J.C.); [email protected] (S.C.S.); [email protected] (S.C.B.); [email protected] (G.C.W.E.) 2 UK Vet Derm, 16 Talbot Street, Whitwick, Leicestershire LE67 5AW, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 May 2019; Accepted: 6 October 2019; Published: 16 October 2019 Simple Summary: Canine atopic dermatitis (cAD) is a common allergic skin condition in dogs that causes long-term itching; it is similar to eczema in people. The overall quality of life in dogs with cAD is known to be reduced, and humans with eczema report significant psychological burdens from itching that increase stress levels and can lead to the development of additional mental health problems. We tested whether dogs with cAD would display more problem behaviours (that could be indicative of stress) than would healthy controls. Behavioural data were gathered directly from owners using a validated dog behaviour questionnaire for 343 dogs with a diagnosis of cAD and 552 healthy controls, and scores were also provided for the severity of itching experienced by their dog. The results showed that itch severity in dogs with cAD was associated with increased frequency of behaviours often considered problematic, such as: mounting, chewing, hyperactivity, coprophagia (eating faeces), begging for and stealing food, attention-seeking, excitability, excessive grooming and reduced trainability. -

Endogenous Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and Aggression in Domestic Dogs

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 27 September 2017 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01613 Endogenous Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and Aggression in Domestic Dogs Evan L. MacLean 1*, Laurence R. Gesquiere 2, Margaret E. Gruen 3, Barbara L. Sherman 4, W. Lance Martin 5 and C. Sue Carter 6 1 School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States, 2 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States, 3 Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States, 4 Department of Clinical Sciences, NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, NC State University, Raleigh, NC, United States, 5 Martin-Protean LLC, Princeton, NJ, United States, 6 Kinsey Institute and Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IA, United States Aggressive behavior in dogs poses public health and animal welfare concerns, however the biological mechanisms regulating dog aggression are not well understood. We investigated the relationships between endogenous plasma oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (AVP)—neuropeptides that have been linked to affiliative and aggressive behavior in other mammalian species—and aggression in domestic dogs. We first validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the measurement of free (unbound) and total (free + bound) OT and AVP in dog plasma. In Experiment 1 we evaluated behavioral and neuroendocrine differences between a population of pet dogs with a history of chronic aggression toward conspecifics and a matched control group. Dogs with a history of aggression exhibited more aggressive behavior -

Genetic Aspects of Dog Behaviour with Particular Reference to Working Ability

i* \ V Genetic aspects of dog behaviour 4 with particular reference to working ability M. B. WILLIS genetic factors, they will also be modified through Introduction interactions with the environment. Anyone using dogs as working animals has an obvi- Humphrey & Warner (1934) calculated pheno- ous interest in knowing: (a) the degree to which typic correlations among 42 physical and 9 behav- specific features are inherited; (b) the magnitude of ioural traits in GSDs, and found that 15 of the 378 the differences which exist between breeds; and (c) possible correlations reached statistical significance. the relationship, if any, between specific traits. It is probable that the underlying genetic correlations Although the dog has had a longer association, and were quite different and that the project was over- enjoys closer contacts, with humans than any other simplified in seeking Mendelian explanations. Never- species, genetic studies on the domestic dog are not theless, the Fortunate Fields study (Humphrey & extensive. Most genetic work has been directed Warner, 1934) did achieve success in producing towards understanding the mode of inheritance of superior animals for guide dog/police work using specific physical anomalies, whereas advanced studies this simplified system. on the inheritance of behaviour are relatively recent The present paper looks at behaviour in guide and stem largely from the pioneering work that led to dogs, hunting dogs, livestock guarding dogs and the publication of Scott & Fuller (1965). Mackenzie, police/service dogs. The importance to man of herd- Oltenacu & Houpt (1986) provided a broad review ing dogs is without question, but so few genetic data of behaviour genetics of the dog, but the present exist in this field that herding dogs are deliberately review focuses specifically on the genetics of working excluded from the present discussion. -

1 Welcome to South Wilton Veterinary Group! We Are Very Excited to Have

51 Danbury Road Wilton, Connecticut 06897 www.southwiltonvet.com Email [email protected] Tel 203 762 2002 Fax 203 834 9999 Welcome to South Wilton Veterinary Group! We are very excited to have you join our growing practice. Please take a moment to sort through this new client welcome folder we have prepared for you. Many frequently asked questions may be answered as we have enclosed information on many important topics related to the proper care of your precious pet. We have enclosed information on: Our Services and Doctors Preventative Health Care Recommendations Microchipping as Permanent Identification for Your Pet Emergency Care for Your Pet Veterinary Pet Insurance Referrals to Specialists in our Area Local Pet Service Recommendations Payment Options and Policies If you have any questions after reviewing this material, feel free to contact us by phone (203-762-2002) or email ([email protected]). You may also visit our website at www.southwiltonvet.com for further information and downloadable materials. The section entitled “Pet Education” contains many helpful handouts. Sincerely, The Doctors and Staff at South Wilton Veterinary Group 1 Directions to Local Emergency Centers If you have an emergency with your dog or cat after hours and we are not available, please go to the Veterinary Referral and Emergency Center in Norwalk, CT or the Cornell University Veterinary Specialists in Stamford, CT. VREC 123 West Cedar Street Norwalk, CT 203-854-9960 From I-95 South: Take Exit 14, at the end turn RIGHT onto route 1, at the next light turn LEFT (N. Taylor Avenue) go 1 block and turn LEFT onto West Cedar Street. -

A Note on the Effectiveness of Behavioural Rehabilitation for Reducing Inter-Dog Aggression in Shelter Dogs

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 8-2008 A Note on the Effectiveness of Behavioural Rehabilitation for Reducing Inter-Dog Aggression in Shelter Dogs Jane S. Orihel University of British Columbia David Fraser University of British Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/intbeh Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Orihel, J. S., & Fraser, D. (2008). A note on the effectiveness of behavioural rehabilitation for reducing inter-dog aggression in shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 112(3), 400-405. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Note on the Effectiveness of Behavioural Rehabilitation for Reducing Inter-Dog Aggression in Shelter Dogs Jane S. Orihel and David Fraser University of British Columbia KEYWORDS canine, dog behaviour, rehabilitation, inter-dog aggression, shelter dogs ABSTRACT The effectiveness of a rehabilitation program for reducing inter-dog aggression was evaluated at the municipal animal shelter. Sixteen dogs (of 60 examined) met the study criteria of medium inter-dog aggression as determined by an inter-dog aggression test. These dogs received a 10-day treatment of daily rehabilitation for 30 min (rehabilitation group, n = 9) or daily release into an outdoor enclosure for 30 min (control group, n = 7). Rehabilitation consisted of desensitising and counter-conditioning dogs to the approach of other ‘‘stimulus’’ dogs. Most dogs in the rehabilitation group showed a decline in aggression scores when re-tested after the last treatment (day 11), and differed significantly from the control dogs which showed either an increase or no change in aggression scores (U = 8.5, P < 0.01).