Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

Standard N° 37

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) SECRETARIAT GENERAL: 13, Place Albert 1er B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique) ______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ 30.03.2009/EN _______________________________________________________________ FCI-Standard N° 37 CÃO DE AGUA PORTUGUÊS (Portuguese Water Dog) 2 TRANSLATION: Portuguese Kennel Club. Revised by R. Triquet & J. Mulholland and Renée Sporre-Willes. Official language (EN). ORIGIN: Portugal. DATE OF PUBLICATION OF THE OFFICIAL VALID STANDARD: 04.11.2008. UTILIZATION: Assistance with fishing and retrieving as well as companion dog. FCI- CLASSIFICATION: Group 8 Retrievers, Flushing Dogs, Water Dogs. Section 3 Water dogs. Without working trial. BRIEF HISTORICAL SUMMARY: In ancient times, the Portuguese Water Dog could be found throughout the entire Portuguese coast. Thereafter, due to continuous changes in fishing methods, the breed was located mainly in the Algarve region which is now considered as its original birthplace. Its presence on the Portuguese coast is probably very remote and thus the Portuguese Water Dog should be considered as an autochthonous Portuguese breed. GENERAL APPEARANCE: A dog of medium proportions, bracoïd tending to rectilinear to slight convex. Harmonious in shape, balanced, strong and well muscled. Considerable development of the muscles due to constant swimming. IMPORTANT PROPORTIONS: Of almost square shape, with the length of body approximately equal to height at the withers. FCI-St. N° 37 / 30.03.2009 3 The ratio of the height at the withers to the depth of the chest is 2:1; the ratio of length of skull to muzzle is 4:3. BEHAVIOUR/TEMPERAMENT: Exceptionally intelligent, it understands and obeys easily and happily any order given by its owner. An animal with impetuous disposition, wilful, courageous, sober and resistant to fatigue. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Dog Owners and Breeders Symposium July 28, 2001 University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine

Dog Owners and Breeders Symposium July 28, 2001 University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine *Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Dogs *Overview of Canine Dental Health and Disease *Nutrition for Working Dogs *Intervertebral Disc Disease *Gastric Dilatation Volvulus *Canine Geriatric Medicine *Research Priorities Identified by AKC Parent Clubs *Current Concepts in Veterinary Ophthalmology *Advanced Reproduction Symposium *Feeding Dogs for Life Stages *An Introduction to Acupuncture *Management of Dogs with Chronic Atopic Dermatitis: What’s New? Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Dogs Patti S. Snyder, DVM, MS, DACVIM Associate Professor, University of Florida General Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a very common form of heart disease in dogs. Only degenerative valve disease (also called mitral valve disease or endocardiosis or mitral insufficiency) and in some places heartworm disease are more common. It was not until the 1970s, when echocardiography began to be performed in veterinary institutions, that dilated cardiomyopathy could be diagnosed non-invasively with any certain degree of accuracy. The reported prevalence in dogs is approximately 0.5 percent. Based upon a national database of dogs presented to veterinary schools in North America, we know that 5.8 percent of the Doberman Pinschers that were seen at a school had DCM, 5.6 percent of the Irish Wolfhounds presented had DCM. 3.9 percent of the Great Danes, 3.4 percent of the Boxers and 2.6 percent of the St. Bernards. The prevalence in purebred dogs in 0.65 percent whereas the prevalence in mixed breed dogs is 0.16 percent. In general, the dogs are middle age (4-10 years of age, with the exception of the Portuguese Water Dog (0.5 – 8 months)). -

Official Standard of the Portuguese Water Dog General Appearance

Page 1 of 3 Official Standard of the Portuguese Water Dog General Appearance: Known for centuries along Portugal's coast, this seafaring breed was prized by fishermen for a spirited, yet obedient nature, and a robust, medium build that allowed for a full day's work in and out of the water. The Portuguese Water Dog is a swimmer and diver of exceptional ability and stamina, who aided his master at sea by retrieving broken nets, herding schools of fish, and carrying messages between boats and to shore. He is a loyal companion and alert guard. This highly intelligent utilitarian breed is distinguished by two coat types, either curly or wavy; an impressive head of considerable breadth and well proportioned mass; a ruggedly built, well-knit body; and a powerful, thickly based tail, carried gallantly or used purposefully as a rudder. The Portuguese Water Dog provides an indelible impression of strength, spirit, and soundness. Size, Proportion, Substance: Size - Height at the withers - Males, 20 to 23 inches. The ideal is 22 inches. Females, 17 to 21 inches. The ideal is 19 inches. Weight - For males, 42 to 60 pounds; for females, 35 to 50 pounds. Proportion - Off square; slightly longer than tall when measured from prosternum to rearmost point of the buttocks, and from withers to ground. Substance - Strong, substantial bone; well developed, neither refined nor coarse, and a solidly built, muscular body. Head: An essential characteristic; distinctively large, well proportioned and with exceptional breadth of topskull. Expression - Steady, penetrating, and attentive. Eyes - Medium in size; set well apart, and a bit obliquely. -

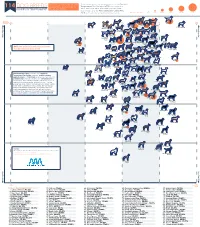

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

AMTC Newsletter

AMTC Newsletter February 2018 BOB Standard Manchester – CH Noble’s Random Reaction at Toria. Bred by Trina Taylor- Ghione and Victoria Herbert -Thorsland. Adrian Ghione, Agent. BV/BOS Toy Manchester – GRC Cottage Lake’s Our Lady of Fatima – Bred and owned by Dr. Roger Travis and Marcelo Chagas More Results!: 2 Results from National, Cont.: 3 Results from National, Cont.: 4 Results from National, Cont.: More 2017 National info is included later in the newsletter. Also, there is news about the 2018 National too!! 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pictures from 2017 National ................................................................................................................... 1 General AMTC Club Information ............................................................................................................. 7 Publishing Dates & Deadlines................................................................................................................. 8 President’s Message .............................................................................................................................. 9 Note from the Editor ............................................................................................................................... 9 AMTC Webmaster Comments ................................................................................................................ 9 Reports from the Secretary ................................................................................................................... 10 New Membership -

The Manchester Terrier

HISTORY OF THE BREED ago. The Manchester Terrier is a very old Appearing in the form we know today in the breed that has been used as the foundation THE MANCHESTER TERRIER late 1800s the longevity of this breed should stock for a number of other breeds as well. be recognized. Writings referring to an What is the difference between a earlier version of the breed (the English standard and a toy? Black and Tan Terrier) date back almost 400 years, making the Manchester one of the In Canada and the United States Manchester oldest breeds of terrier currently recognized Terriers come in 2 varieties, a standard and a by the Canadian Kennel Club. toy. According to the breed standards put out by the CKC and the AKC the only differences between the 2 varieties are size This pamphlet will help explain what our Originally bred as a "ratting machine" and ear type. The standard Manchester wonderful breed is all about, but there is no Manchester's made frequent and highly Terrier should weigh between 12-22 pounds, better way to find out about Manchesters acclaimed appearances in the rat pits. the toy should weigh less than 12 pounds. And than spending time with one (or many!). while the toy Manchester Terrier only has 1 acceptable ear type (naturally erect), 3 ear During the late 19th century the popularity For further information on the breed, or types are acceptable for the standard of the breed fell with the outlawing of blood to locate a breeder contact Manchester Terrier (cropped, button, and sports and the banning of ear cropping. -

A Quick Assessment Tool for Humandirected Aggression in Pet

AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR Volume 9999, pages 1–11 (2013) A Quick Assessment Tool for Human‐Directed Aggression in Pet Dogs Barbara Klausz1, Anna Kis1,2, Eszter Persa1, Ádám Miklósi1,3, and Márta Gácsi1,3* 1Department of Ethology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary 2Research Centre for Natural Sciences, Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychology, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary 3MTA‐ELTE Comparative Ethology Research Group, Budapest, Hungary .......................................... Many test series have been developed to assess dog temperament and aggressive behavior, but most of them have been criticized for their relatively low predictive validity or being too long, stressful, and/or problematic to carry out. We aimed to develop a short and effective series of tests that corresponds with (a) the dog’s bite history, and (b) owner evaluation of the dog’s aggressive tendencies. Seventy‐three pet dogs were divided into three groups by their biting history; non‐biter, bit once, and multiple biter. All dogs were exposed to a short test series modeling five real‐life situations: friendly greeting, take away bone, threatening approach, tug‐of‐war, and roll over. We found strong correlations between the in‐test behavior and owner reports of dogs’ aggressive tendencies towards strangers; however, the test results did not mirror the reported owner‐directed aggressive tendencies. Three test situations (friendly greeting, take‐away bone, threatening approach) proved to be effective in evoking specific behavioral differences according to dog biting history. Non‐biters differed from biters, and there were also specific differences related to aggression and fear between the two biter groups. When a subsample of dogs was retested, the test revealed consistent results over time. -

The Manchester Terrier Is One Breed With

The Manchester Terrier: Description and History: Description: The Manchester is a hardy and long-lived breed. They are very adaptable and make an excellent and devoted companion for most people. Equally at home in the country or city, the Manchester is intelligence, versatile, and naturally clean in his habits. This has prompted breed fanciers to conclude that “As a sagacious, intelligent house pet and companion, no breed is superior to the well-bred Manchester Terrier." (AKC's Complete Dog Book) In America, the Manchester Terrier is considered to be one breed with two varieties: the Standard and the Toy. The Toy variety can weigh up to 12 pounds and has only naturally erect ears. The Standard variety weighs over 12 pounds but not over 22 pounds, and may have three ear types: cropped, button, or naturally erect like the Toys. (See pictures below). Cropped ears Button ears Naturally Erect ears Photograph and computer imagery by Carolyn Horowitz In both varieties, the only allowable color is black and tan. This accounts for the breed's original name -- the Black and Tan Terrier. The placement and brilliant contrast of the tan markings against the black face and the black markings against the tan legs, while occurring naturally, are essential to the dog's work as a ratter. A cornered rat will always go for its attacker's eyes to disable it; the bright tan spots around the less visible black eyes of the Manchester Terrier draw the rat to leap for the spots and miss its intended target. Following is a short history of the development of the Manchester Terrier in England and America.