Gauging U.S.-Indian Strategic Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Management Accountant

7+(0$1$*(0(17 THE MANAGEMENT ACCOUNTANT ACCOUNTANT THE MANAGEMENT SEPTEMBER 2016 9 51 NO. VOL. 7+(-2851$/)25&0$V $&&2817$17 ,661 6HSWHPEHU92/123DJHV ÃÌÊ «iÌÌÛiiÃÃ ` 100 «iÝÌÞÊÌÊ v`iVi 7+(,167,787(2)&267$&&2817$1762),1',$ 6WDWXWRU\ERG\XQGHUDQ$FWRI3DUOLDPHQW ZZZLFPDLLQ www.icmai.in September 2016 The Management Accountant 1 2 The Management Accountant September 22016 www.icmai.in The Institute of Cost Accountants of India PRESIDENT THE INSTITUTE OF COST ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA CMA Manas Kumar Thakur (erstwhile The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants [email protected] of India) was first established in 1944 as a registered VICE PRESIDENT CMA Sanjay Gupta company under the Companies Act with the objects of [email protected] promoting, regulating and developing the profession of COUNCIL MEMBERS Cost Accountancy. CMA Amit Anand Apte, CMA Ashok Bhagawandas Nawal, On 28 May 1959, the Institute was established by a CMA Avijit Goswami, CMA Balwinder Singh, special Act of Parliament, namely, the Cost and Works CMA Biswarup Basu, CMA H. Padmanabhan, Accountants Act 1959 as a statutory professional body for CMA Dr. I. Ashok, CMA Niranjan Mishra, CMA Papa Rao Sunkara, CMA P. Raju Iyer, the regulation of the profession of cost and management CMA Dr. P V S Jagan Mohan Rao, accountancy. CMA P. V. Bhattad, CMA Vijender Sharma It has since been continuously contributing to the Shri Ajai Das Mehrotra, Shri K.V.R. Murthy, growth of the industrial and economic climate of the Shri Praveer Kumar, Shri Surender Kumar, country. Shri Sushil Behl The Institute of Cost Accountants of India is the only Secretary recognised statutory professional organisation and CMA Kaushik Banerjee, [email protected] licensing body in India specialising exclusively in Cost Sr. -

Annual Report 1991-92

ANNUAL REPORT 1991-92 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD BOMBAY ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD Shri S.D. Soman ... Chairman Dr. R.D. Lele ... Member Consultant Physician and Director of Nuclear Medicine, Jaslok Hospital & Research Centre, Bombay. Dr. S.S. Ramaswamy ... Member Retd. Director General, Factory Advice Service & Labour Institute Bombay. Dr. A. Ciopalakrishnan ... Member Director, Central Mechanical Engineering Research Institute Durgapur S.Vasant Kumar ... Ex-officio Chairman, Member Safety Review Committee for Operating Plants (SARCOP), Bombay Dr. K.S. Parthasarathy ... Secretary Dy. Director, AERB Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, Vikram Sarabhai Bhavari, Anushakti Nagar, Bombay-400 094. ATOMIC ENERGY REGULATORY BOARD The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board was constituted on November 15. 1983 by the President of India by exercising the powers conferred by Section 27 of the Atomic Energy Act 1962 (33 of 1962) to cany out certain regulatory and safety functions under the Act The regulatory authority (Annexure-I) of AERB is derived from rules and notifications promulgated under the Atomic Energy Act 1962 and Environmental Protection Act 1986 The mission of the Beard is to ensure that the use of ionizing radiation and nuclear energy in India does not cause undue risk to health safety and the environment The Board consists of a full time Chairman, an ex-officio Member, three part time Members and a Secretary The bio-data of its members is given in Annexure-ll AERB is supported by th? Advisory Committees for Proiect Salety Review (ACPSRs one for the nuclear power projects and the other for heavy water projects) Ihe Safely Review Committee for Operating Plants (SARCOP) and Salety Review Committee for Applications ol Radiation (SARCARt The memberships of these committees are given in Annexure-lll The ACPSR recommends to the AERB. -

Magazine Can Be Printed in Whole Or Part Without the Written Permission of the Publisher

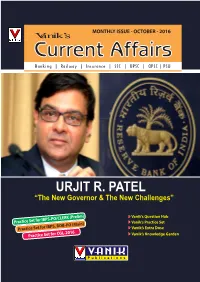

MONTHLY ISSUE - OCTOBER - 2016 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU URJIT R. PATEL “The New Governor & The New Challenges” Vanik’s Question Hub -PO/CLERK (Prelim) Practice Set for IBPS Vanik’s Practice Set -PO (Main) Practice Set for IBPS, BOB Vanik’s Extra Dose GL-2016 Practice Set for C Vanik’s Knowledge Garden P u b l i c a t i o n s VANIK'S PAGE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS OF INDIA NAME OF THE AIRPORT CITY STATE Rajiv Gandhi International Airport Hyderabad Telangana Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International Airport Amristar Punjab Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport Guwaha ti Assam Biju Patnaik International Airport Bhubaneshwar Odisha Gaya Airport Gaya Bihar Indira Gandhi International Airport New Delhi Delhi Andaman and Nicobar Veer Savarkar International Airport Port Blair Islands Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International Airport Ahmedabad Gujarat Kempegowda International Airport Bengaluru Karnatak a Mangalore Airport Mangalore Karnatak a Cochin International Airport Kochi Kerala Calicut International Airport Kozhikode Kerala Trivandrum International Airport Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Raja Bhoj Airport Bhopal Madhya Pradesh Devi Ahilyabai Holkar Airport Indore Madhya Pradesh Chhatrapati Shivaji International Airport Mumbai Maharashtr a Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport Nagpur Maharashtr a Pune Airport Pune Maharashtra Zaruki International Airport Shillong Meghalay a Jaipur International Airport Jaipur Rajasthan Chennai International Airport Chennai Tamil Nadu Civil Aerodrome Coimbator e Tamil Nadu Tiruchirapalli International Airport Tiruchirappalli Tamil Nadu Chaudhary Charan Singh Airport Lucknow Uttar Pradesh Lal Bahadur Shastri International Airport Varanasi Uttar Pradesh Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose International Airport Kolkata West Bengal Message from Director Vanik Publications EDITOR Dear Students, Mr. -

HIGHLIGHTS Special Topics: Technical Insights: News Throughout the Region: NEWS INDIA& MIDDLE EAST

OCTOBER / NOVEMBER HIGHLIGHTS 2020 - ISSUE 11 Special Topics: SPOTLIGHT ON Johan Sverdrup: a Norwegian megaproject 7 JD Jones poised for explosive Regional Focus: Karnataka 11 growth Interview: IMI Regional President Mr Tarak Chhaya 15 With strong leadership, a clear strategy, and the ability to quickly adapt to changing circumstances, JD Jones Technical Insights: is a real force in the manufacture Compliant valve stem seals reduce emissions 13 and supply of fluid sealing products. The product range – including gland Could hydrogen be the ideal green fuel? 17 packings, seals, compression packings, PFTE products, etc – finds widespread Automation upgrade for Assam’s tea gardens 22 use in a diverse mix of industries around the world. The company has INDIA & MIDDLE EAST News throughout the Region: also forged win-win partnerships with many leading valvemakers, as Valve 2, 6, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 24 World India & Middle East discovered when speaking recently to CEO The insiders guide to flow control in India, Iran, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Azerbaijan, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, UAE, Bangladesh Mr. Ashish Bajoria. “When Covid-19 struck India in February we of course complied fully Specialist in : with the lockdown. But we did not Multiport allow ourselves to be cowed down by the situation, far from it. We continued Ball Valves to support our clients to the very best Distributors of our ability. Moreover, we used this Wanted period as the ideal opportunity to brainstorm about new markets. I am therefore delighted to say that since Available at February 2020 we have in fact opened JD CONTROLS up four new product verticals.” www.multiportballvalves.com Continued on page 4 NEWS NFC’s plans for a new facility at Kota by 2022 RIL - 1st Indian company to hit $200bn mcap A new facility of the city-based dles, which will be produced at Read more on page 2. -

E-Newsletter Volume 1 Issue 1 November 2019

Volume-1 Issue-1 For Internal Private Circulation only FROM CHAIRMAN’S DESK Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali Chairman IIChE-MRC Indian Institute Of Chemical Engineers is a confluence of streams of professionals from academia, research institute and industry. It was founded by Dr. Hira Lal Roy before Indian Independence in order to cluster stalwarts in Chemical Engineering from various professions to support the chemical industries as well as Institutes by providing a forum for interaction and joint endeavors. IIChE- MRC conducts and supports many events through out the year and feels it prudent to share its achievements with all members. Hence, IIChE-MRC decided to publish this quarterly e- newsletter for the benefit of all members from academia, research institute, industry and student chapters to gain acquaintance with current events, technical articles on Industry and upcoming events of IIChE-MRC. I hope that this e-newsletter proves beneficial to the chemical engineering as well as allied sciences readers and encourage them to take up joint ventures with immense participation towards the Nation building. Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali IIChEMRC Executive Committee Dr. U. Kamachi Mudali, Hon. Chairman Mr. Rajesh Jain Member Dr Anita Kumari Hon. Vice Chairperson Mr. Ravindra Joshi Member Dr. Alpana Mahapatra Member Dr. Bibhash Chakravorty Hon. Secretary Dr. T.L. Prasad Member Mr. Dhawal Saxena Hon. Jt Secretary Mr. V.Y.Sane Member Mr. Mahendra Patel Hon. Treasurer Mr. Joy Shah Member Mr. Shreedhar .M. Chitanvis Member Dr. Aparna M. Tamaskar Member INDIAN INSTITUTE OF CHEMICAL ENGINEERS Mumbai Regional Centre B-18, Vardhman Complex, Gr Floor, Opp Home Town & 247 Park, LBS Marg, Vikhroli (West), Mumbai - 400 083 1 November 2019 IICHE MRC E-NEWSLETTER 1 Volume-1 Issue-1 INDEX From Chairman’s Desk / IICHEMRC Executive Committee Index / Editor’s Corner / Disclaimer Recent Events / Forthcoming Events • Workshop on Solid Waste Management on 24/09/2019 at IITB I by NAE, IITB, IIChE & IEA. -

The-Hindu-Special-Diary-Complete

THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 2 DIARY OF EVENTS 2015 THE HINDU THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 panel headed by former CJI R. M. Feb. 10: The Aam Aadmi Party NATIONAL Lodha to decide penalty. sweeps to power with 67 seats in the Indian-American author Jhumpa 70-member Delhi Assembly. JANUARY Lahiri wins the $ 50,000 DSC prize Facebook launches Internet.org for Literature for her book, The in India at a function in Mumbai. Jan. 1: The Modi government sets Lowland . ICICI Bank launches the first dig- up NITI Aayog (National Institution Prime Minister Narendra Modi ital bank in the country, ‘Pockets’, on for Transforming India) in place of launches the Beti Bachao, Beti Pad- a mobile phone in Mumbai. the Planning Commission. hao (save daughters, educate daugh- Feb. 13: Srirangam witnesses The Karnataka High Court sets up ters) scheme in Panipat, Haryana. over 80 per cent turnout in bypolls. a Special Bench under Justice C.R. “Sukanya Samrudhi” account Sensex gains 289.83 points to re- Kumaraswamy to hear appeals filed scheme unveiled. claim 29000-mark on stellar SBI by AIADMK general secretary Jaya- Sensex closes at a record high of earnings. lalithaa in the disproportionate as- 29006.02 Feb. 14: Arvind Kejriwal takes sets case. Jan. 24: Poet Arundhati Subra- oath as Delhi’s eighth Chief Minis- The Tamil Nadu Governor K. Ro- manian wins the inaugural Khush- ter, at the Ramlila Maidan in New saiah confers the Sangita Kalanidhi want Singh Memorial Prize for Delhi. award on musician T.V. Gopalak- Poetry for her work When God is a Feb. -

Nuclear Power Business Executive V P L&T Ltd

11TH NUCLEAR ENERGY CONCLAVE Steering Committee Dr S Banerjee Shri Anil Razdan Dr. R. B. Grover Chairman, Nuclear Energy President, IEF & Member, AEC & Group, IEF, Chancellor, Homi Former Secretary,Power Former Vice Chancellor Bhabha National Institute Homi Bhabha & Former Chairman, AEC & National Institute Secretary, DAE Ms. Minu Singh Shri V.P. Singh Shri P.P. Yadav Shri Anil Parab M.D., Nuvia India Former ED, BHEL ED (Nuclear Power Business Executive V P L&T Ltd. Development), BHEL Dr Harsh Mahajan Shri Amarjit Singh, MBE Shri S.C. Chetal Shri S.M. Mahajan Director, Mahjan Imaging Secretary General, IEF Former Director, IGCAR & Convener, Nuclear Group, Mission Director, AUSC Project IEF, Former ED, BHEL & Consultant (Power Sector) Organiser India Energy Forum: The Forum is a unique, independent, not-for-profit, research organization and represents energy sector as a whole. It is manned by highly qualified and experienced energy professionals committed to evolving a national energy policy. The Forum's mission is the development of a sustainable and competitive energy sector, promoting a favourable regulatory framework, establishing standards for reliable and safety, ensuring an equitable deal for consumers, producers and the utilities, encouraging efficient and eco-friendly development and use of energy and developing new and better technologies to meet the growing energy needs of the society. Its membership includes all the key players of the sector including BHEL, NTPC, NHPC, Power Grid Corporation, Power Finance Corporation, Reliance Energy, Alstom and over 100 highly respected energy experts. It works closely with various chambers and trade associates including Bombay Chamber, Bengal Chamber, Madras Chamber, PHD Chamber, Observer Research Foundation, IRADE, INWEA,Indian Coal Forum, and FIPI. -

Management of the Indian Nuclear Fuel Fabrication Facilities During COVID – 19 Pandemic

Department of Atomic Energy Nuclear Fuel Complex Hyderabad – Pazhayakayal – Kota Online Webinar Management of the Indian Nuclear Fuel Fabrication Facilities during COVID – 19 Pandemic Dr. Dinesh Srivastava Distinguished Scientist Chairman & Chief Executive IAEA Online Webinar: Maintaining Nuclear Safety of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities during Pandemic 1 Outline Introduction Fulfillment of NFC commitment Infrastructure development Covid-19 protection plan during production New norm post covid-19 Summary. IAEA Online Webinar: Maintaining Nuclear Safety of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities during Pandemic 2 Fuel Bundles Manufactured at NFC 220 MWe PHWR 540 MWe PHWR 160 MWe BWR (RAPS 3&4) (TAPS 3&4) (TAPS 1&2) 19 Element Bundle 37 Element Bundle 6 × 6 BWR Bundle 16.5 kg in Weight 23.8 kg in Weight 203 kg in Weight IAEA Online Webinar: Maintaining Nuclear Safety of Nuclear Fuel Cycle Facilities during Pandemic 3 PHWR Fuel Manufacturing Process MDU / SDU / Washed and Dissolution HTUP / UOC Dried Frit Dissolution Solvent Extraction Solvent Extraction Precipitation Precipitation Drying Filtration Calcination Drying Reduction Calcination Stabilization Grinding Nuclear Grade Nuclear Grade UO2 Powder ZrO2 Powder Blending Precompaction Coking Granulation UO Green 2 Final Compaction Pellets Chlorination Sintering Reduction Centreless Grinding Vacuum Distillation Sponge Handling Washing & Drying Zircaloy Stacking Ingots Compaction End Machining Alloying UO2 Green Appendage Welding Pellets EB Welding Graphite Coating -

Long Term Sustainability of Nuclear Power in India - Prospects and Challenges

Page | 45 5 LONG TERM SUSTAINABILITY OF NUCLEAR POWER IN INDIA - PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES Vipin Shukla, Vivek J. Pandya and C. Ganguly ABSTRACT: Nuclear power is emerging as a viable for at least 12 additional indigenous PHWR 700 carbon – free option for India to meet the ever- reactors. The target is to have ~ 45,000 MWe nuclear increasing demand of base – load electricity at an power by 2030. Since the last six years, India has affordable price, in a safe, secured and sustainable also been importing natural uranium oreconcentrate manner. Since the 1970s, India had been pursuing (UOC) and finished natural UO2 pellets tofuel the a self-reliant indigenous nuclear power program ten PHWR 220 units at Rawathbhata, Kakrapara and linking the fuel cycles of Pressurized Heavy Water Narora. India has also been importing enriched UO2 Reactor (PHWR), Fast Breeder Reactor (FBRs) and fuel for the two BWRs at Tarapur and the two VVERs thorium-based self-sustaining breeder in stage 1, 2 at Kudankulunm. The present paper summarizes the and 3 respectively, for efficient utilization of modest on-going and the expanding nuclear power program low grade (0.03-0.06 % U3O8) uranium reserves but in India highlighting the challenges of availability of vast thorium resources. Natural uranium fueled uranium and plutonium for manufacturing nuclear PHWR is the backbone of the program. India has fuels. achieved industrial maturity in PHWR and the related uranium fuel cycle technology. Presently, 21 reactors are in operation, including 16 units of PHWR 220 MWe, 2 units of PHWR 540 MWe, 2 units of Boiling Water Reactor (BWR) 160 MWe and a (Water KEYWORDS Water Energy Reactor) VVER 1000 MWe. -

Cost Reduction and Safety Design Features of New Nuclear Power Plants in India

XA0201901 Annex 13 Cost reduction and safety design features of new nuclear power plants in India V.K. Sharma Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd, India Abstract. Indian Nuclear Power Programme is designed to exploit limited reserves of uranium and extensive resource of thorium. Pressurised heavy water reactors are found most suitable and form the main stay of the first stage of the programme. Thorium utilisation is achieved in the second & third stages. Today India has total installed capacity of 2720 MWe of PHWRs which are operating with high plant load factors of over 80%. Rich experience of construction and operation of over 150 reactor years is being utilised in effecting cost reduction and safety improvements. Standardisation and reduction in gestation period by preproject activities, advance procurement and work packages of engineer, procure, construct and commission are some of the techniques being adopted for cost reduction in the new projects. But the cost of safety is rising. Design basis event of double ended guillotine rupture of primary pressure boundary needs a relook based on current knowledge of material behaviour. This event appears improbable. Similarly some of the safety related systems like closed loop cooling water operating at low temperature and pressure, and low usage factors may be designed as per standard codes without invoking special nuclear requirements. The paper will address these issues and highlight the possible areas for cost reduction both in operating and safety systems. Modern construction and project management techniques are being employed. Gestation period of 5 years and cost of less than US $1400 per KWe are the present targets. -

Nuclear Energy in India's Energy Security Matrix

Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 2 of 55 About the Author Maj Gen AK Chaturvedi, AVSM, VSM was commissioned in Corps of Engineers (Bengal Sappers) during December 1974 and after a distinguished career of 38 years, both within Engineers and the staff, retired in July 2012. He is an alumnus of the College of Military Engineers, Pune; Indian Institute of Technology, Madras; College of Defence Management, Secunderabad; and National Defence College, New Delhi. Post retirement, he is pursuing PhD on ‘India’s Energy Security: 2030’. He is a prolific writer, who has also been quite active in lecture circuit on national security issues. His areas of interests are energy, water and other elements of ‘National Security’. He is based at Lucknow. http://www.vifindia.org © Vivekananda International Foundation Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 3 of 55 Abstract Energy is essential for the economic growth of a nation. India, which is in the lower half of the countries as far as the energy consumption per capita is concerned, needs to leap frog from its present position to upper half, commensurate with its growing economic stature, by adopting an approach, where all available sources need to be optimally used in a coordinated manner, to bridge the demand supply gap. A new road map is needed to address the energy security issue in short, medium and long term. Solution should be sustainable, environment friendly and affordable. Nuclear energy, a relatively clean energy, has an advantage that the blueprint for its growth, which was made over half a century earlier, is still valid and though sputtering at times, but is moving steadily as envisaged.