Vascular Plant Anatomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gymnosperms the MESOZOIC: ERA of GYMNOSPERM DOMINANCE

Chapter 24 Gymnosperms THE MESOZOIC: ERA OF GYMNOSPERM DOMINANCE THE VASCULAR SYSTEM OF GYMNOSPERMS CYCADS GINKGO CONIFERS Pinaceae Include the Pines, Firs, and Spruces Cupressaceae Include the Junipers, Cypresses, and Redwoods Taxaceae Include the Yews, but Plum Yews Belong to Cephalotaxaceae Podocarpaceae and Araucariaceae Are Largely Southern Hemisphere Conifers THE LIFE CYCLE OF PINUS, A REPRESENTATIVE GYMNOSPERM Pollen and Ovules Are Produced in Different Kinds of Structures Pollination Replaces the Need for Free Water Fertilization Leads to Seed Formation GNETOPHYTES GYMNOSPERMS: SEEDS, POLLEN, AND WOOD THE ECOLOGICAL AND ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF GYMNOSPERMS The Origin of Seeds, Pollen, and Wood Seeds and Pollen Are Key Reproductive SUMMARY Innovations for Life on Land Seed Plants Have Distinctive Vegetative PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Features ENVIRONMENT: The California Coast Relationships among Gymnosperms Redwood Forest 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. The evolution of seeds, pollen, and wood freed plants from the need for water during reproduction, allowed for more effective dispersal of sperm, increased parental investment in the next generation and allowed for greater size and strength. 2. Seed plants originated in the Devonian period from a group called the progymnosperms, which possessed wood and heterospory, but reproduced by releasing spores. Currently, five lineages of seed plants survive--the flowering plants plus four groups of gymnosperms: cycads, Ginkgo, conifers, and gnetophytes. Conifers are the best known and most economically important group, including pines, firs, spruces, hemlocks, redwoods, cedars, cypress, yews, and several Southern Hemisphere genera. 3. The pine life cycle is heterosporous. Pollen strobili are small and seasonal. Each sporophyll has two microsporangia, in which microspores are formed and divide into immature male gametophytes while still retained in the microsporangia. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Beyond Plant Blindness: Seeing the Importance of Plants for a Sustainable World

Sanders, Dawn, Nyberg, Eva, Snaebjornsdottir, Bryndis, Wilson, Mark, Eriksen, Bente and Brkovic, Irma (2017) Beyond plant blindness: seeing the importance of plants for a sustainable world. In: State of the World’s Plants Symposium, 25-26 May 2017, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, London, UK. (Unpublished) Downloaded from: http://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/4247/ Usage of any items from the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository ‘Insight’ must conform to the following fair usage guidelines. Any item and its associated metadata held in the University of Cumbria’s institutional repository Insight (unless stated otherwise on the metadata record) may be copied, displayed or performed, and stored in line with the JISC fair dealing guidelines (available here) for educational and not-for-profit activities provided that • the authors, title and full bibliographic details of the item are cited clearly when any part of the work is referred to verbally or in the written form • a hyperlink/URL to the original Insight record of that item is included in any citations of the work • the content is not changed in any way • all files required for usage of the item are kept together with the main item file. You may not • sell any part of an item • refer to any part of an item without citation • amend any item or contextualise it in a way that will impugn the creator’s reputation • remove or alter the copyright statement on an item. The full policy can be found here. Alternatively contact the University of Cumbria Repository Editor by emailing [email protected]. -

Synthetic Conversion of Leaf Chloroplasts Into Carotenoid-Rich Plastids Reveals Mechanistic Basis of Natural Chromoplast Development

Synthetic conversion of leaf chloroplasts into carotenoid-rich plastids reveals mechanistic basis of natural chromoplast development Briardo Llorentea,b,c,1, Salvador Torres-Montillaa, Luca Morellia, Igor Florez-Sarasaa, José Tomás Matusa,d, Miguel Ezquerroa, Lucio D’Andreaa,e, Fakhreddine Houhouf, Eszter Majerf, Belén Picóg, Jaime Cebollag, Adrian Troncosoh, Alisdair R. Ferniee, José-Antonio Daròsf, and Manuel Rodriguez-Concepciona,f,1 aCentre for Research in Agricultural Genomics (CRAG) CSIC-IRTA-UAB-UB, Campus UAB Bellaterra, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; bARC Center of Excellence in Synthetic Biology, Department of Molecular Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; cCSIRO Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform, Sydney NSW 2109, Australia; dInstitute for Integrative Systems Biology (I2SysBio), Universitat de Valencia-CSIC, 46908 Paterna, Valencia, Spain; eMax-Planck-Institut für Molekulare Pflanzenphysiologie, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany; fInstituto de Biología Molecular y Celular de Plantas, CSIC-Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; gInstituto de Conservación y Mejora de la Agrodiversidad, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain; and hSorbonne Universités, Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Génie Enzymatique et Cellulaire, UMR-CNRS 7025, CS 60319, 60203 Compiègne Cedex, France Edited by Krishna K. Niyogi, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved July 29, 2020 (received for review March 9, 2020) Plastids, the defining organelles of plant cells, undergo physiological chromoplasts but into a completely different type of plastids and morphological changes to fulfill distinct biological functions. In named gerontoplasts (1, 2). particular, the differentiation of chloroplasts into chromoplasts The most prominent changes during chloroplast-to-chromo- results in an enhanced storage capacity for carotenoids with indus- plast differentiation are the reorganization of the internal plastid trial and nutritional value such as beta-carotene (provitamin A). -

PLANT ANATOMY Lecture 15 - Stele and Bundle Types

Jim Bidlack - BIO 5354/4354 PLANT ANATOMY Lecture 15 - Stele and Bundle Types I. Types of steles (stellar types); stele refers to the central vascular network if the shoot and the root (includes outermost phloem and everything to the inside of it) A. Protostele 1. No pith and usually no separate vascular bundles 2. First pattern (phylogenetically) that appeared in vascular plants 3. Predominant pattern found in roots of almost all plants and shoots of lower vascular plants 4. Types of protostele a) Haplostele - xylem is a circular mass b) Actinostele - xylem margin is not smooth; it "undulates" c) Plectostele - xylem not one mass; series of plates B. Siphonostele 1. Has a pith and can have separate vascular bundles (primary growth) 2. More advanced plants 3. Found in shoots of seed plants and in roots having a broad stele (monocots) 4. Types of siphonostele a) Amphiphloic - phloem found on both sides of the xylem 1) Solenostele - very few or little leaf gaps widely separated (continuous cylinder) 2) Dictyostele - leaf gaps are abundant b) Ectophloic - phloem found only to outside of the xylem 1) Eustele (dicots) - one ring of vascular bundles surround a pith 2) Atactostele (monocots) - scattered bundle arrangement II. Stellar patterns at the node (Nodal pattern) A. Different because this is where leaves and buds are attached B. Area above & behind the leaf or bud is the leaf gap C. Area showing where the leaf (bundle(s)) attaches to stem is called leaf trace D. Examples of patterns: 1. Unilacunar, 1 trace; unilacunar, 3 trace; trilacunar, 3 trace III. -

Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species

rch: O ea pe es n A R t c s c Rodriguez et al., Forest Res 2016, 5:3 e e r s o s Forest Research F DOI: 10.4172/2168-9776.1000183 Open Access ISSN: 2168-9776 Research Article Open Access Research Advances on Leaf and Wood Anatomy of Woody Species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub Forest and its Significance in Taxonomy and Drought Resistance Rodriguez HG1*, Maiti R1 and Kumari A2 1Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Carr. Nac. No. 85 Km. 45, Linares, Nuevo León 67700, México 2Plant Physiology, Agricultural College, Professor Jaya Shankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Polasa, Jagtial, Karimnagar, Telangana, India Abstract The present paper make a synthesis of a comparative leaf anatomy including leaf surface, leaf lamina, petiole and venation as well as wood anatomy of 30 woody species of a Tamaulipan Thorn Scrub, Northeastern Mexico. The results showed a large variability in anatomical traits of both leaf and wood anatomy. The variations of these anatomical traits could be effectively used in taxonomic delimitation of the species and adaptation of the species to xeric environments. For example the absence or low frequency of stomata on leaf surface, the presence of long palisade cells, and presence of narrow xylem vessels in the wood could be related to adaptation of the species to drought. Besides the species with dense venation and petiole with thick collenchyma and sclerenchyma and large vascular bundle could be well adapted to xeric environments. It is suggested that a comprehensive consideration of leaf anatomy (leaf surface, lamina, petiole and venation) and wood anatomy should be used as a basis of taxonomy and drought resistance. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

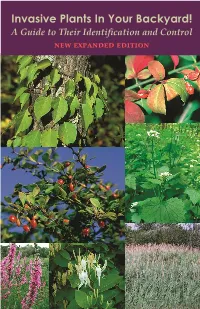

Invasive Plants in Your Backyard!

Invasive Plants In Your Backyard! A Guide to Their Identification and Control new expanded edition Do you know what plants are growing in your yard? Chances are very good that along with your favorite flowers and shrubs, there are non‐native invasives on your property. Non‐native invasives are aggressive exotic plants introduced intentionally for their ornamental value, or accidentally by hitchhiking with people or products. They thrive in our growing conditions, and with no natural enemies have nothing to check their rapid spread. The environmental costs of invasives are great – they crowd out native vegetation and reduce biological diversity, can change how entire ecosystems function, and pose a threat Invasive Morrow’s honeysuckle (S. Leicht, to endangered species. University of Connecticut, bugwood.org) Several organizations in Connecticut are hard at work preventing the spread of invasives, including the Invasive Plant Council, the Invasive Plant Working Group, and the Invasive Plant Atlas of New England. They maintain an official list of invasive and potentially invasive plants, promote invasives eradication, and have helped establish legislation restricting the sale of invasives. Should I be concerned about invasives on my property? Invasive plants can be a major nuisance right in your own backyard. They can kill your favorite trees, show up in your gardens, and overrun your lawn. And, because it can be costly to remove them, they can even lower the value of your property. What’s more, invasive plants can escape to nearby parks, open spaces and natural areas. What should I do if there are invasives on my property? If you find invasive plants on your property they should be removed before the infestation worsens. -

Plant Classification

Plant Classification Vascular plants are a group that has a system Non-Vascular plants are low growing plants of tubes (roots, stems and leaves) to help that get materials directly from their them transport materials throughout the surroundings. They have small root-like plant. Tubes called xylem move water from structures called rhizoids which help them the roots to the stems and leaves. Tubes adhere to their substrate. They undergo called phloem move food from the leaves asexual reproduction through vegetative (where sugar is made during propagation and sexual reproduction using photosynthesis) to the rest of the plant’s spores. Examples include bryophytes like cells. Vascular plants reproduce asexually hornworts, liverworts, and mosses. through spores and vegetative propagation (small part of the plant breaks off and forms a new plant) and sexually through pollen (sperm) and ovules (eggs). A gymnosperm is a vascular plant whose An angiosperm is a vascular plant whose seeds are not enclosed in an ovule or fruit. mature seeds are enclosed in a fruit or The name means “naked seed” and the ovule. They are flowering plants that group typically refers to conifers that bear reproduce using seeds and are either male and female cones, have needle-like “perfect” and contain both male and female leaves and are evergreen (leaves stay green reproductive structures or “imperfect” and year round and do not drop their leaves contain only male or female structures. during the fall and winter. Examples include Angiosperm trees are also called hardwoods pine trees, ginkgos and cycads. and they have broad leaves that change color and drop during the fall and winter. -

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees

The Genomics of Wood Formation in Angiosperm Trees Xinqiang He and Andrew T. Groover Abstract Advances in genomic science have enabled comparative approaches that can evaluate the evolution of genes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic traits relevant to angiosperm forest trees. Wood formation is an excellent subject for com- parative genomics, as it is an ancestral trait for angiosperms and has undergone significant modification in different angiosperm lineages. This chapter discusses some of the traits associated with wood formation, what is currently known about the genes and mechanisms regulating these traits, and how comparative evolution- ary genomic studies can be undertaken to provide more comprehensive views of the evolution and development of wood formation in angiosperms. Keywords Wood formation • Wood development • Wood evolution • Transcriptional regulation • Epigenetics • Comparative genomics Genomic Perspectives on the Evolutionary Origins and Variation in Angiosperm Wood Introduction The evolutionary and developmental biology of wood are fundamental to under- standing the amazing diversification of angiosperms. While flower morphology and reproductive characters associated with angiosperms have been the focus of numer- ous genetic and genomic evo-devo studies, wood development is a relatively neglected trait of angiosperm evolution and development that is now tractable for comparative and evolutionary genomic studies. The ability to produce wood from a X. He School of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China A.T. Groover (*) Pacific Southwest Research Station, US Forest Service, Davis, 95618 CA, USA Department of Plant Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, 95618 CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing AG 2017 205 A.T. Groover and Q.C.B. -

Week 1 Topic: Plant Anatomy Reading: Chapter 42, Sections 1-3 I Have A

Biology 103, Spring 2008 Dr. Karen Bledsoe Notes http://www.wou.edu/~bledsoek/ Week 1 Reading: Chapter 42, sections 1-3 Topic: Plant anatomy I have a friend who’s an artist, and he sometimes takes a view which I don’t agree with. He’ll hold up a flower and say, “Look how beautiful it is,” and I’ll agree. But then he’ll say, “I, as an artist, can see who beautiful a flower is. But you, as a scientist, take it all apart and it becomes quite dull.” I think he’s kind of nutty... There are all kinds of interesting questions that come from a knowledge of science, which only adds to the excitement and mystery of a flower. It only adds. Richard Feynman, What Do You Care What Other People Think? (1989, p. 11) Main concepts: • The cell is the basic unit of all living things. Tissues are made up of one or more types of cells, organs are made up of tissues, and systems are made up of organs. Most groups of multicellular organisms, including plants, are made up of multiple organ systems. • The organs and organ systems of a plant include roots (root system), stems, leaves, and flowers (shoot system) • Plants are divided into two broad groups, the monocots (single cotyledon in the seed) and dicots (two cotyledons in the seed). A number of structural differences make these two groups fairly easy to tell apart: • monocots: 3 petals and 3 sepals (though the sepals may look like the petals), parallel veins in the leaves, fibrous root system. -

Effect of Stele Type in the Growth Rotation of Dalbergia Melanoxylon

International Journal of Plant and Forestry Sciences Vol. 2, No. 3, May 2015, pp. 1 -10 Available online at http://ijpfs.com/ Research article Effect of Stele type in the growth rotation of Dalbergia melanoxylon. Dr. Washa B. Washa Mkwawa University College of Education Private Bag, MUCE Iringa Tanzania. E-mail: [email protected], +255 752 356 709 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Examination of the effect of stele type in Dalbergia melanoxylon growth was conducted. Examination of stems to observe stele type and tissue water potential of Barreveld Faux, Cupressus sempervirens and Dalbergia melanoxylon was carried between 2nd – 23rd April 2015 at Mkwawa University Laboratories. About 120 stained stem sections were examined for stele type while other 120 stem pieces were incubated in Nacl solution for water potential. Forty (40) stained sections indicated ectophloic siphonostele in Barreveld Faux and C. sempervirens while 40 sections of D. melanoxylon indicated atactostele. Calculated water potential of Barreveld Faux was -0.01158597 bars and that of C. sempervirens was -0.01257201 bars while that of D. melanoxylon was -0.00320463 bars. Results found that, low water potential in D. melanoxylon is a factor for its slow growth rotation and this is due to the atactostele type existing in D. melanoxylon. A hard Blackwood and valued wood in D. melanoxylon is brought by this stele type. In order to initiate rapid growth rotation in D. melanoxylon is recommended to conduct genetic recombination of the D. melanoxylon with other species which have an easily growing wood although this can lower the hardwood quality and value of the D.