100002603.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

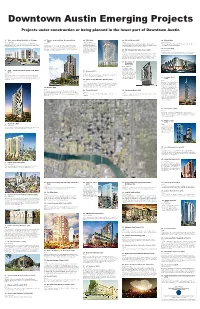

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects Projects under construction or being planned in the lower part of Downtown Austin 1. 7th & Lamar (North Block, Phase II) (C2g) 11. Thomas C. Green Water Treatment Plant 20. 7Rio (R60) 28. 5th and Brazos (C54) 39. Eleven (R86) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ (C56) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ Planned 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ &RQVWUXFWLRQLVXQGHUZD\DWWKHVLWHRIWKHIRUPHU.$6(.9(7UDGLR Planned &RQVWUXFWLRQVWDUWHGLQ0D\ $QH[LVWLQJYDOHWSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLOOEHWRUQGRZQDQGUHSODFHGE\DQ :RUNFRQWLQXHVRQWKLVXQLWPXOWLIDPLO\SURMHFWRQ(WK6WUHHW VWXGLREXLOGLQJIRUWKHFRQVWUXFWLRQRIDQHZSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWK 7KH*UHHQVLWHZLOOFRQVLVWRIVHYHUDOEXLOGLQJVXSWRVWRULHVWDOO RQWKLVXQLWDSDUWPHQW HLJKWVWRU\SDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWKVSDFHV7KDWJDUDJHVWUXFWXUHZLOODOVR RYHUORRNLQJ,DQGGRZQWRZQ$XVWLQ VIRIJURXQGÀRRUUHWDLO ,QFOXGLQJ%ORFN VHHEHORZ WKHSURMHFWZLOOKDYHPLOOLRQ WRZHUDW:WK6WUHHWDQG5LR LQFOXGHVTXDUHIHHWRIVWUHHWOHYHOUHWDLOVSDFH VTXDUHIHHWRIGHYHORSPHQWLQFOXGLQJDSDUWPHQWVVTIWRI *UDQGHE\&DOLIRUQLDEDVHG RI¿FHVSDFHDURRPKRWHODQGVTIWRIUHWDLO PRVWDORQJDQ GHYHORSPHQWFRPSDQ\&:6 40. Corazon (R66) H[WHQVLRQRIWKHQG6WUHHW'LVWULFW 7KHSURMHFWZDVGHVLJQHG 29. 5th & Brazos Mixed-Use Tower (C89) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ E\ORFDODUFKLWHFWXUDO¿UP Planned 5KRGH3DUWQHUV &\SUHVV5HDO(VWDWH$GYLVHUVLVEXLOGLQJ&RUD]RQDYHUWLFDOPL[HGXVH $VN\VFUDSHURIXSWRVWRULHVZLWKKRWHOURRPVDQGUHVLGHQFHVDW(DVW SURMHFWWKDWZLOOLQFOXGHUHVLGHQWLDOXQLWVUHWDLODQGDUHVWDXUDQW )LIWKDQG%UD]RVVWUHHWVGRZQWRZQ7KHWRZHUFRXOGLQFOXGHRQHRUWZR KRWHOVDQGPRUHWKDQKRXVLQJXQLWVPRVWOLNHO\DSDUWPHQWV&KLFDJR EDVHG0DJHOODQ'HYHORSPHQW*URXSZRXOGGHYHORSWKHSURMHFWZLWK :DQ[LDQJ$PHULFD5HDO(VWDWH*URXSDOVREDVHGLQWKH&KLFDJRDUHD -

MATERIAL SUPPORTING the AGENDA Volume Xvib January 1969

>9 MATERIAL SUPPORTING THE AGENDA Volume XVIb January 1969 - May 1969 This volume contains the Material Supporting the Agenda furnished to each member of the Board of Regents prior to the meetings held on January 31-February 1, March 14, and May 2, 1969. The material is divided according to the Standing Com mittees and the meetings that were held and is submitted on three different colors, namely: (1) white paper - for the documentation of all items that were presented before the deadline date (2) blue paper - all items submitted to the Executive Session of the Com mittee of the VJhole and distributed only to the Regents, Chancellor, and Chancellor Emeritus (3) yellow paper - emergency items distributed at the meeting Material distributed at the meeting as additional docu mentation is not included in the bound volume, because sometimes there is an unusual amount and other times maybe some people get copies and some do not get copies. If the Secretary were furnished a copy, then that material goes in the appropriate subject folder. THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM Material Supporting i Agenda MeetmgDate: M^ch 14, 1969 4 H Meeting No.: , CALENDAR BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYSTEM March 14, 1969 Place: U. T. Austin, Main Building Meeting Room: Main Building, Suite 212 Friday, March 14, 1969--The Committees will meet in the order set out below, followed by the Meeting of the Board: 9:00 a.m. Executive Committee Academic and Developmental Affairs Committee Buildings and Grounds Committee Medical Affairs Committee Land and Investment Committee Committee of the Whole Meeting of the Board Lunch will be served at noon in Main Building 101. -

The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan

ORDINANCE NO. 040826-56 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING THE AUSTIN TOMORROW COMPREHENSIVE PLAN BY ADOPTING THE CENTRAL AUSTIN COMBINED NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN. BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF AUSTIN: PARTI. Findings. (A) In 1979, the Cily Council adopted the "Austin Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan." (B) Article X, Section 5 of the City Charter authorizes the City Council to adopt by ordinance additional elements of a comprehensive plan that are necessary or desirable to establish and implement policies for growth, development, and beautification, including neighborhood, community, or area-wide plans. (C) In December 2002, the Central Austin neighborhood was selected to work with the City to complete a neighborhood plan. The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan followed a process first outlined by the Citizens' Planning Committee in 1995, and refined by the Ad Hoc Neighborhood Planning Committee in 1996. The City Council endorsed this approach for neighborhood planning in a 1997 resolution. This process mandated representation of all of the stakeholders in the neighborhood and required active public outreach. The City Council directed the Planning Commission to consider the plan in a 2002 resolution. During the planning process, the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team gathered information and solicited public input through the following means: (1.) neighborhood planning team meetings; (2) collection of existing data; (3) neighborhood inventory; (4) neighborhood survey; (5) neighborhood workshops; (6) community-wide meetings; and (7) a neighborhood final survey. Page 1 of 3 (D) The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan recommends action by the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team, City staff, and by other agencies to preserve and improve the neighborhood. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

List for August 2009 Update.Xlsx

The University of Texas System FY 2010-2015 Capital Improvement Program Summary by Funding Source CIP Project Cost Funding Source Total % of Total Bond Proceeds PUF $ 645,539,709 7.8% RFS 2,473,736,000 29.8% TRB 823,808,645 9.9% Subtotal Bond Proceeds 3,943,084,354 47.5% Institutional Funds Aux Enterprise Balances $ 22,349,500 0.3% Available University Fund 7,600,000 0.1% Designated Funds 33,261,100 0.4% Gifts 1,107,556,900 13.3% Grants 191,425,000 2.3% HEF 4,744,014 0.1% Hospital Revenues 1,844,920,000 22.2% Insurance Claims 553,200,000 6.7% Interest On Local Funds 113,360,315 1.4% MSRDP 98,900,000 1.2% Unexpended Plant Funds 383,635,739 4.6% Subtotal Institutional Funds 4,360,952,568 52.5% Capital Improvement Program Total Funding Sources $ 8,304,036,922 100% Quarterly Update 8/20/09 F.1 The University of Texas System FY 2010-2015 Capital Improvement Program Summary by Institution CIP Number of Project Cost Institution Projects Total Academic Institutions U. T. Arlington 10 $ 306,353,376 U. T. Austin 47 1,401,616,150 U. T. Brownsville 2 50,800,000 U. T. Dallas 16 268,079,750 U. T. El Paso 13 214,420,000 U. T. Pan American 5 92,517,909 U. T. Permian Basin 4 150,239,250 U. T. San Antonio 13 152,074,000 U. T. Tyler 7 58,159,300 Subtotal Academic Institutions 117 2,694,259,735 Health Institutions U. -

SEPTEMBER 2004 Any Persons Living Or Dead Is Coincidental

THE h o t t i e OF THE LINING BIRDCAGES SINCE 1997 FRENCH ISSUE month EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Todd Nienkerk olores MANAGING EDITOR Kristin Hillery DESIGN DIRECTOR JJ Hermes Gifter of Bibles ASSOCIATE Elizabeth Barksdale EDITORS Ryan B. Martinez D WRITING STAFF Kathryn Edwards Who is this hot Magdalenian mama beckoning me to her Bradley Jackson Fertile Crescent? Your lips, swollen with Passion, coax me into Chanice Jan Todd Mein the sizzling sinlessness of scripture. Did you spill some Holy John Roper Joel Siegel Water on your lap, or are you just anticipating the Rapture? Christie Young Press me against your virginal bosom so I can be DESIGN STAFF David Strauss born again, and again — and again! Christina Vara ADVERTISING Emily Coalson vital stats PUBLICITY Stan Babbitt Hobbies: Accepting missionary positions, being an open book, shopping at the Dress Barn, DISTRIBUTION Stephanie Bates “Bible”-beating, being on her knees WEBMASTER Mike Kantor ADMINISTRATIVE Erica Grundish Turn-ons: submission, “Dogma,” destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abel SUPERVISOR Turn-offs: Getting off the high horse, abridging, “The DaVinci Code”, polytheism, birth ADMINISTRATIVE Leala Ansari control, Cain, lap dances, Darwin, the Pope-mobile ASSISTANTS Doug Cooper Jef Greilich Sara Kanewske meeting at busy intersections to play right-of-way • People running to class look funny and deserve to Lindsay Meeks games with speeding vehicles. be laughed at. Jill Morris Garrett Rowe • Overeager returning students will continue to • The 40 Acres Buses will be renamed “40- Toby Salinger like school enough for the both of you. Thousand Acres.” If they weren’t traveling 40,000 Ari Schulman around • Captain Clueless will attempt to charm you by acres, why else would they take so goddamn long Laura Schulman turning courteous small talk into a biographical and travel caravan-style? Eric Seufert discourse about himself. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

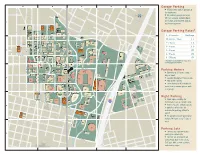

Parking Map for UT Campus

Garage Parking n Visitors may park in garages at the hourly rate n All parking garages are open 24/7 on a space-available basis for visitors and students and do not require a permit Garage Parking Rates* 0-30 minutes No Charge 30 minutes - 1 hour $ 3 1 - 2 hours $ 6 2 - 3 hours $ 9 3 - 4 hours $12 4 - 8 hours $15 8 - 24 hours $18 * Rates and availability may vary during special events. Parking Meters n Operational 24 hours a day, 7 days a week n Located throughout the campus n 25¢ for 15 minutes n Time limited to 45 minutes. If more time is needed, please park in a garage Night Parking n Read signs carefully for restrictions such as “At All Times” Bob B n ulloc After 5:45 p.m., certain spaces Texas k State Histo M ry useum in specific surface lots are available for parking without a permit n All garages provide parking for visitors 24 hours a day, 7 days a week Parking Lots n There is no daytime visitor parking in surface lots n Permits are required in all Tex surface lots from 7:30 a.m. to as Sta Ca te pitol 5:45 p.m. M-F as well as times indicated by signs BUILDING DIRECTORY CRD Carothers Dormitory .............................A2 CRH Creekside Residence Hall ....................C2 J R Public Parking CS3 Chilling Station No. 3 ...........................C4 JCD Jester Dormitory ..................................... B4 RHD Roberts Hall Dormitory .........................C3 CS4 Chilling Station No. 4 ...........................C2 BRG Brazos Garage .....................................B4 JES Beauford H. Jester Center ....................B3 RLM Robert Lee Moore Hall ..........................B2 CS5 Chilling Station No. -

Center for Texas Public History Department of History Texas State University

INTERSECT 1 An Online Journal from the Center for Texas Public History Department of History Texas State University Spring, 2020 INTERSECT 2 INTERSECT: PERSPECTIVES IN TEXAS PUBLIC HISTORY Spring 2020 Introduction 4 A City Upon A Hill Country: 5 The Story of the Antioch Colony Amber Leigh Hullum “Something That Can Identify Us”: 15 A History of the San Marcos Dunbar School and Community Center Katherine Bansemer Divided Audiences: 23 The Story and Legacy of San Marcos’s Segregated Cinema Katherine Bansemer, Amber Leigh Hullum, Charlotte Nickles Erasing Community Identity: 30 The Dark History of East Austin’s Forgotten School Eric Robertson-Gordon “Sports Breaks Down All Barriers”: 37 High School Sports Integration in San Marcos, Texas David Charles Robinson INTERSECT 3 Editorial Staff Katherine Bansemer Managing Editor Amber Leigh Hullum Managing Editor David Charles Robinson Production Manager Eric K. Robertson-Gordon Production Assistant Charlotte Nickles Production Assistant Dan K. Utley Faculty Advisor INTERSECT 4 Introduction When work began on this journal in January 2020, it seemed like an ordinary semester. The central objective that drove the early planning in January and February was to compile scholarly site-based articles about Jim Crow racial policies in Central Texas. What are the vestiges of the policies that remain visible well into the twenty- first century? As the discussions moved forward, the parameters of the journal changed considerably, although the focus remained on the local era of segregation. Then, as the project entered its research phase, word began to spread about a new strain of virus confounding containment efforts in Asia, Europe, and beyond. -

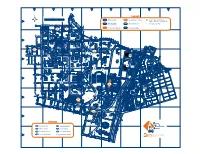

Legend Garages

A B C D E F G H SAN SCALE: FEET Legend 0 500 250 500 JACINTO TPS Parking Garage Special Access Parking K Kiosk / Entry Control Station 1 (open 7:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. M-F) 2700 BLVD. Metered Parking Restricted Access Emergency Call Box 300W 200W 100W 100E 400W Active 24 hours W. 27TH ST. ARC FUTURE SITE Official Visitor Parking Construction Zone AVE. NRH TSG ST. SWG NOA AVE. SW7 LLF LLC CS5 BWY 2600 NSA LLE LLB 2600 2600 2600 LLD LLA 2600 CPE GIA KIN UA9 WICHITA ETC FDH NO PARKING SSB SEA WHITIS ST. 200E KEETON 500E 2 300W W. DEAN 200W 100W 100E KEETON ST. 300E 400E E. DEAN SHC 2500 ST. LTD NMS ECJ TNH ST. CMA RLM JON WWH CMB 2500 BUR 2500 SHD 2500 800E W. 25TH ST. CS4 600E CREEK CCJ UNIVERSITY CMC 2500 AHG MBB SPEEDWAY CTB DEV BLD WICHITA W 25th ST. CRD E. 500E 25th ST 900E LCH ENS . ST. SAG PHR PAT SER SJG AND 2400 DR. 2400 PHR SETON ANTONIO MRH MRH LFH ST. TCC CREEK 2400 GEA ESB WRW 2400 WOH SAN 300W K GRG 2400 1100E NUECES ST. W. 24th ST. E. 24th 300E ST. 2400 TMM K 200W 100W 100E 200E K E. DEAN E. 28th IPF YOUNG QUIST DA PPA BIO PAI ST. 3 ACE PPE Y DEDMAN KEETON WEL IT BOT WALLER IN 2300 R HMA BLVD. T 2300 PAC 200W 100W PPL ART LBJ PP8 NUECES ST. TAY ST. UNB FDF ST. DFA 1600E GEB CS2 ST. -

• FEBRUARY 07.Indd

to Bars, Bands and Boutiques Next Door by Laura Mohammad Life Photography by Barton Wilder Custom Images an domestic bliss at Seaholm that would be thirty-fi ve hun- dominiums at 1212 Guadalupe St., coming on downtown, says downtown Austin can be found in a small dred to forty-fi ve hundred square feet. At from a Villas on Town Lake unit at 80 Red be a home for families as well. He and his downtown condo? last count, Staley says they have met with River St. that was more than three hundred wife share a Milago condo at 54 Rainey St. Yes, according to as many as twelve developers about expan- square feet bigger. Less space doesn’t mat- with their toddler and baby. Downtown has Marc Perlman, who sion possibilities. ter to her. stroller destinations for the girls, complete lives with his prized Staley says he knew Royal Blue would She’s always out and about, she says, with a walk through the park. The Burns- CD collection, book- be a hit downtown. What surprised him biking everywhere, whether feeding the es even do their shopping at Whole Foods Cshelves, bed, and not by stroller. much else in a condo Burns is one of about fi fty-eight hun- of seven hundred ninety-two square feet in dred residents living in the area defi ned by the Avenue Lofts, at 400 E. Fifth St. the City of Austin as downtown: I-35 to Perlman loves his loft. More than loves Lamar and Martin Luther King to the north it. -

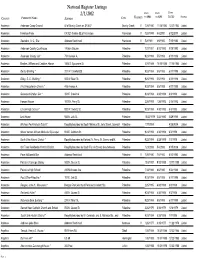

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE to SBR to NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY

National Register Listings 2/1/2012 DATE DATE DATE TO SBR TO NPS LISTED STATUS COUNTY PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY VICINITY AndersonAnderson Camp Ground W of Brushy Creek on SR 837 Brushy Creek V7/25/1980 11/18/1982 12/27/1982 Listed AndersonFreeman Farm CR 323 3 miles SE of Frankston Frankston V7/24/1999 5/4/2000 6/12/2000 Listed AndersonSaunders, A. C., Site Address Restricted Frankston V5/2/1981 6/9/1982 7/15/1982 Listed AndersonAnderson County Courthouse 1 Public Square Palestine7/27/1991 8/12/1992 9/28/1992 Listed AndersonAnderson County Jail * 704 Avenue A. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonBroyles, William and Caroline, House 1305 S. Sycamore St. Palestine5/21/1988 10/10/1988 11/10/1988 Listed AndersonDenby Building * 201 W. Crawford St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonDilley, G. E., Building * 503 W. Main St. Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonFirst Presbyterian Church * 406 Avenue A Palestine9/23/1994 5/5/1998 6/11/1998 Listed AndersonGatewood-Shelton Gin * 304 E. Crawford Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonHoward House 1011 N. Perry St. Palestine3/28/1992 1/26/1993 3/14/1993 Listed AndersonLincoln High School * 920 W. Swantz St. Palestine9/23/1994 4/30/1998 6/3/1998 Listed AndersonLink House 925 N. Link St. Palestine10/23/1979 3/24/1980 5/29/1980 Listed AndersonMichaux Park Historic District * Roughly bounded by South Michaux St., Jolly Street, Crockett Palestine1/17/2004 4/28/2004 Listed AndersonMount Vernon African Methodist Episcopal 913 E.